Summary

Key takeaways

European government bond supply is set to rise sharply in 2026 as large fiscal deficits -- particularly in Germany and France -- drive higher net issuance and gross issuance near €1.4 trillion, raising refinancing costs, especially on five‑year paper. ECB quantitative tightening will reduce its purchases, making net‑net issuance the largest on record and materially increasing the free float.

Continued euro‑denominated public issuance, a possible shift towards short-dated bills, and stronger demand from repatriating European investors, insurers and pension funds could absorb much of the extra supply. Country impacts will vary, with Germany the largest nominally and smaller markets facing bigger increases.

European government bond indices are likely to expand in 2026 due to high fiscal deficits in the largest European economies and a continued trend towards more euro-denominated public issuance. Demand from the ECB will shrink further due to quantitative tightening. However, repatriation from European investors and more purchases by insurers and pension funds could be enough to meet the increased supply.

Large deficits in the largest economies

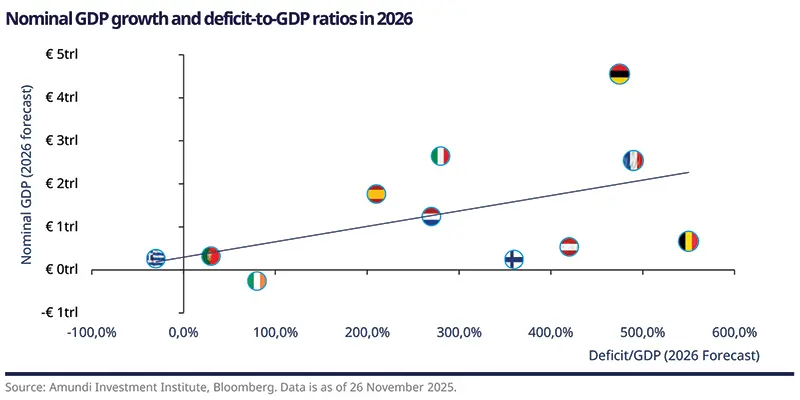

The change in a country’s net debt depends to a small extent on changes in cash balances, but is mostly driven by fiscal deficits. European countries face different fiscal situations in 2026, with Belgium expected to run a deficit of 5.5%, while Greece should enjoy a surplus of 0.3%. However, as the chart below shows, two of the three largest economies – Germany and France – are expected to run two of the three biggest deficits as a share of GDP. Net issuance in France and Germany alone is likely to be half the total increase in Eurozone government net issuance in 2026.

Gross issuance to increase interest costs

Gross issuance depends on net issuance plus redemptions and buy-backs (that is, when countries decide to repurchase debt that will mature later than 2026, to smooth out the redemption schedule). Given the expected steepening in the yield curves in the first half of 2026 and the upward translation in curves since 2022, we suspect buy-backs will be lower than in previous years. However, even with no buybacks, gross issuance across European governments should total close to €1.4 trillion, implying a significant rise in financing costs, especially for maturing five-year debt (issued during the post-Covid period of record-low yields in 2021).

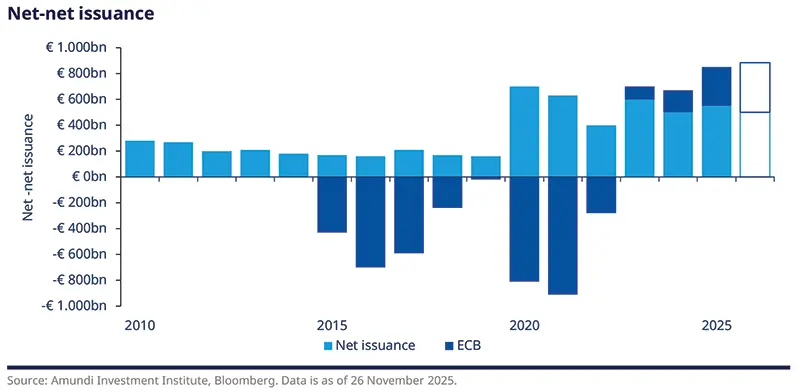

Positive net issuance means European governments need to find new buyers for their bonds. In some years, the ECB has filled that role; between 2015 and 2021, ECB purchases totalled more than the increase in net supply in every year except one. However, since 2023 the ECB has been shrinking its balance sheet, which means that the increase in supply net of the ECB (net-net issuance) has been bigger than net issuance. We expect this to accelerate in 2026, with the ECB due to reduce its holdings by around €384 billion (or slightly more than three quarters of net issuance). Net-net issuance should thus be the highest ever.

More public issuance and perhaps more bills

European governments can finance their debt in various ways: through euros or other currencies, through bills or bonds, in fixed, floating, variable or inflation-linked coupons, and through public sales or directly to retail investors. The long-term trend has been more issuance through the public euro-denominated markets. Prior to 2011, European governments financed between 50% and 60% of their debt in euro-denominated government bond and bill markets. Since the 2011 crisis, this percentage has risen steadily, reaching 69% of total government debt in Q3 2025. We believe the preference for public euro-denominated bond and bill sales will remain and expect 90% of next year’s net issuance to be done through such public sales.

However, one other long-lived trend may now start to change. Over the past twenty years, bond issuance has increased relative to bills. In 2002, bills represented around 10% of total government issuance; by 2025, that percentage had dropped to 6%, largely due to the increase in inflation-linked bonds. Given the steepening of yield curves, European governments may now choose to increase short-dated issuance, just as the US Treasury has signalled it will. This may not prevent further curve steepening, but it could nonetheless slightly reduce financing costs.

Putting all this analysis together, our forecasts suggest that the increase in net debt should be the equivalent of around 5% of outstanding European government debt (and a larger percentage of the European government bond indices, which do not include all European government debt). The increase in net-net demand – the ‘free float’ of European government bonds – should be closer to 8%.

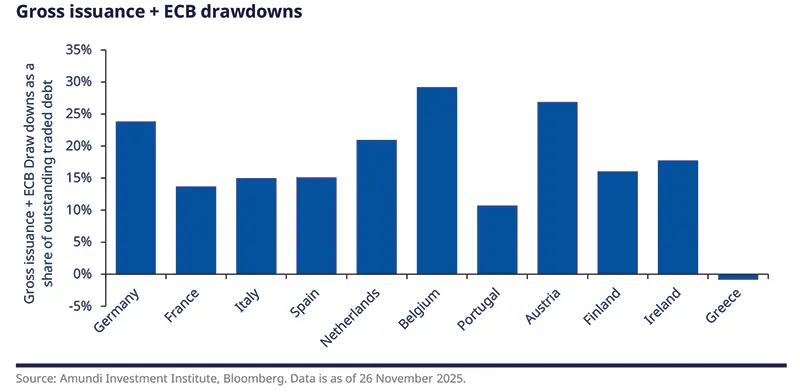

The increase will be quite different by country. The biggest increase in nominal terms should be in Germany, given the €120 billion increase in net financing and the greater than €100bn reduction in ECB holdings. However, the largest percentage increases should be in Belgium and Austria, given the smaller size of their outstanding debt. Even countries with small financing needs, like Ireland, will see an increase in the free float of debt, due to the current smaller size of their markets.

Sources of new fixed income supply

Given the increase in bond issuance and the reduction in demand from the ECB, it is worth wondering who will buy all the new bonds. We see at least three possible ways to meet this increase in demand:

First, we believe European investors may repatriate some funds from other markets back into European bonds. German 10-year yields are currently some 40bp higher than US ten-year yields swapped back into euros, while for most of the past ten years, US swapped yields have been 50bp higher than European yields. European yields thus look relatively attractive.

Second, we suspect that the higher level of European yields in general may drive inflows into insurers’ guaranteed investment contracts, increasing demand for European fixed income. The combination of higher yields in 2022 and relatively stable yields over the past two years should be favourable for inflows into insurance contracts.

Finally, we believe that the switch from defined-benefit to defined-contribution schemes in the Netherlands could counterintuitively increase demand for bonds. When beneficiaries are responsible for their own decisions, they are often more defensive than professional money managers. ECB data shows that the average defined-contribution scheme has a significantly higher share of bonds than the average defined-benefit scheme, even after the rise in yields since 2022.

In summary, though the rise in net-net supply in 2026 and beyond will significantly increase the size of the European sovereign bond indices, repatriation and flows into insurers and pension funds could be enough to meet this demand without generating significantly higher yields.