- Major central banks are reducing their large balance sheets. This will increase the supply of government debt that markets have to absorb, causing upward pressure on yields at a time where deficits are still high.

- The amount and speed at which central banks can offload their holdings critically depends on how much more debt governments issue. Additional public sector spending demands can complicate the tightening path.

- This higher supply of bonds should increase yields and raise the risk-adjusted required returns on other major asset classes. But it should be manageable if it’s done gradually and with due regard to market conditions.

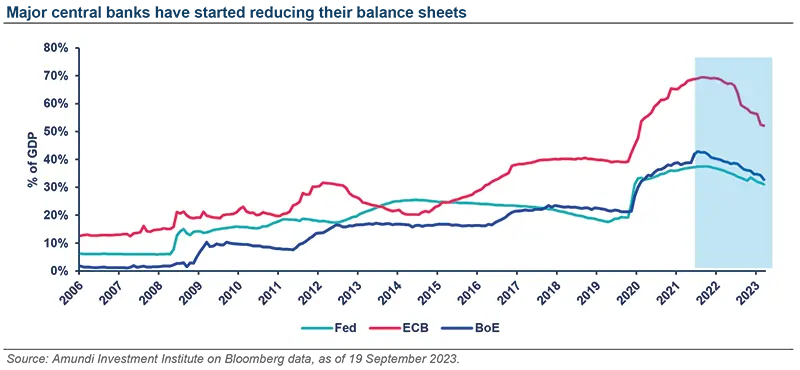

The recent surge in global bond yields is partly ascribed to market worries about a greater supply of debt coming from governments. Some of this increase in yields should reverse when inflation nears central banks’ targets and monetary policy is less restrictive. But central banks will also add to the supply of government bonds over time as they unwind their unprecedentedly large balance sheets – ranging from 30% of GDP for the US Federal Reserve (Fed) to 50% of Eurozone GDP for the European Central Bank (ECB) – substantially larger than the average amount of around 10% of GDP that central banks held before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).

The Bank of England (BoE), the ECB, and the Fed have already begun unwinding through the reduced reinvestment of maturing assets, and all three have indicated that they plan to normalise their balance sheets substantially over time. Their objective is to get ‘out of the unconventional mode’ and operate monetary policy primarily through interest rates. Some central bank officials may also want to put more government debt in market hands as part of the toolkit to tighten policy.

Whether they can pull this off in an orderly way without triggering much higher yields, with markets being asked to absorb a much larger amount of debt, remains to be seen against a backdrop where governments continue to run large deficits. It will also depend on how fast they normalise, how much is unwound and how much more government debt markets will be asked to fund.

The unwinding will need to be gradual, likely spread over many years, because central bank bond holdings are large – about USD 8tn at the Fed, EUR 5tn at the ECB and GBP 800bn at the BoE. A gradual exit would also reduce their potential losses as they reinvest maturing assets into higher-yielding debt compared to the low-yielding bonds they bought during the period of low interest rates.

Some central bankers have argued that long-term balance sheets will almost certainly need to be much larger than before either the GFC or the beginning of unconventional monetary policies such as Quantitative Easing (QE). Due to the secular growth of debt markets, frequent policy interventions to achieve financial stability objectives, a higher demand for bank reserves and more cash in circulation, central banks will inevitably hold larger balance sheets than before QE. Steady state balance sheets of about 20% of GDP on average would be a reasonable assumption.

Over a sufficiently long horizon – ten years plus – this should be manageable, but it will critically depend on how much debt governments issue. The US fiscal outlook is particularly worrisome. Current projections from the US Congressional Budget Office show US Federal debt increasing from USD 33tn this year, to well over USD 50tn by 2033. Paradoxically, if the Fed held 20% of GDP, its balance sheet in ten years’ time would be similar to what it is now while, at the same time, the market would hold a lot more US government debt. In the Eurozone and the UK, the outlook is a little more sanguine, thanks to more prudent fiscal plans. But here, too, there will be little room for fiscal manoeuvre, and fiscal consolidation plans will be challenging if yields remain high.

Central banks’ plans for reducing their balance sheets may also be thwarted by other demands for borrowing, including from the public sector. While much of the very large financing required for the transition to net zero will have to come from the private sector, the public sector’s contribution could be substantial. A more adverse geopolitical outlook may increase demands for higher defence spending. All these additional demands could lead to structurally higher interest rates that central banks will need to contend with.

An important implication is that quantitative tightening will need to be conducted with due regard to financial conditions and the market’s appetite for government debt. A formulaic annual reduction programme, or a fixed end target may not be ideal, or even feasible.

The shift to a less accommodative monetary policy stance will make bonds more attractive over time. The added supply of government bonds should push market yields higher, particularly on longer maturities, causing some degree of yield curve steepening. Countries with bigger debt burdens could see a larger increase in their borrowing costs. However, the trajectory of rates will not be linear, so investors should adopt a flexible approach to duration. But a long enough time horizon and gradual policy shift should provide ample time for markets to adapt. Domestic investors will also play a bigger role in absorbing the additional supply of their government’s bonds.

The new higher-yield environment is already generating strong demand from investors who want to lock in higher long-term income to match their longer-term liabilities. Higher returns on the safest benchmark government bonds mean other riskier assets like equities, which offer a premium, will have to be priced more attractively. Compared to the accommodative policies of the quantitative-easing period, there should be less indiscriminate appreciation of asset prices. Investors will have to focus more on corporate fundamentals and identifying technological and productivity changes.

For more insights

To learn more about this topic, click on the article below: