Summary

Key Takeaways

|

Introduction

From November 10th to November 22nd 2025, the 30th Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, more commonly referred to as COP30, was held in Belém, Brazil. This was the first COP ever hosted in the Amazon region, and it was the second most attended COP after COP28 in Dubai. This conference is the largest annual international meeting on climate organized by the United Nations, since 1992: government representatives come together to attempt to agree on action for the climate crisis. With time, the conference has gathered also financial actors, corporates and civil society, with commitments going beyond policy making.

Ten years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, climate diplomacy is at a crossroad. In 2015, the basic operating system of global climate governance was established: a collective temperature goal, a cycle of national climate plans (NDCs), and the commitment to align global financial flows with a low-emissions and climate-resilient pathway.

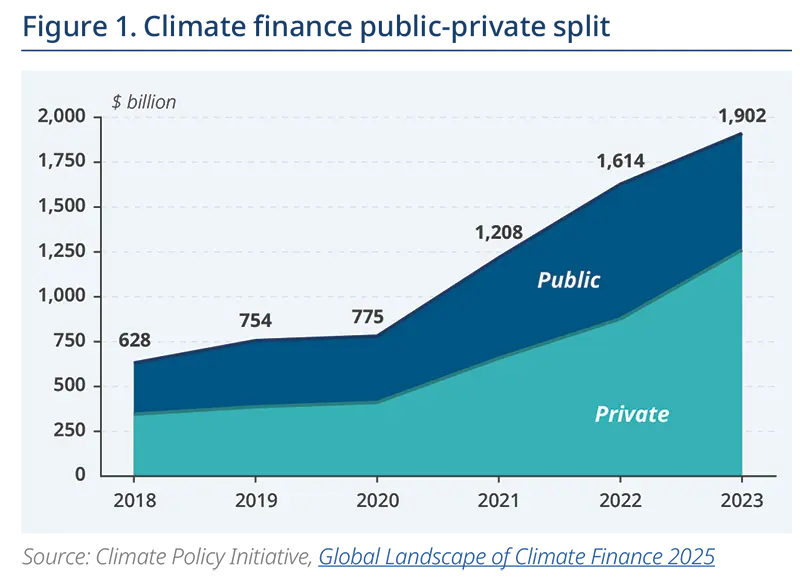

A decade later, the picture is more complex. Global emissions have not yet peaked: the latest UNEP Emissions Gap Report still places the world on a 2.8°C trajectory under current policies vs. almost 4°C in 2015. Physical impacts have intensified, with climate-related losses now counted in the hundreds of billions of dollars per year. Climate finance has expanded dramatically — from roughly $600 billion in 2015 to nearly $2 trillion today — but flows remain highly concentrated, especially towards OECD economies and China.

Polarization in major economies, rising sovereign debt in developing countries, and the imminent withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement are all part of a strained system. The trust gap between developed and developing countries — already visible at COP29 in Baku — has widened.

But not all is lost: despite political fragmentation, investments in renewables are still double those of fossil fuels since last year, displaying technological progress and the viability of low-carbon alternatives. Climate financing needs are higher than ever, on the public and the private side.

COP30 disappointed many stakeholders with high expectations on this anniversary-COP, especially with parties being unable to agree on a language to phase out fossil fuels or halt deforestation. Though COP30 did not produce a grand political breakthrough and did not close the ambition or finance gap, some important outcomes must be highlighted:

It confirmed that the Paris machinery of national plans remains functional, even if under stress

It sketched the clearest financial architecture to date through the Baku–to-Belém roadmap,outlining a pathway towards mobilizing $1.3 trillion in climate finance per year by 2035

It marked the operationalization of the Loss & Damage Fund

It saw the emergence of early Article 6 transactions and a new carbon market coalition

It hosted the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility, an unprecedented attempt to mobilize long-term capital for forest conservation.

Ten years after Paris, COP30 was not the broad remobi-lisation many had hoped for — but a recalibration. Its outcomes help to clarify how the system is likely to operate over the next decade: more fragmented geopolitically, more focused on implementation than negotiation, more dependent on the financial system — and, crucially, more reliant on private investment to close the gap between ambition and reality.

1. National climate plans: politically mixed signals, yet still investable

As signatories of the Paris Agreement, countries were expected to submit updated and enhanced to their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – national climate plans to contribute to the achievement of the Agreement’s objectives – by February 2025. When the UNFCCC released its first synthesis report in early autumn 2025, only 64 parties had submitted their NDCs, with many major emitters still absent. Before COP30, this gave the impression that the global climate ambition was losing momentum, especially combined with the challenging political environment.

And yet, in the weeks leading up to Belém, a substantial number of countries submitted their updated NDCs, including several key economies. The European Union lodged its revised contribution, reconfirming its -55% target for 2030 and introducing an indicative –65 to –70% range for 2035. China submitted its goal of reducing its GHG emissions to 7–10% below its peak levels by 2035. By the time COP30 started on November 10th, updated NDCs cover around 70% of global greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions, and raised the tally to 113 countries with a national climate plan. Some countries submitted new NDCs during COP30 as well. While the percentage of global GHG emissions covered by policies has increased, NDCs submitted before COP30 achieved less than 14% of the additional emissions reductions needed by 2035 to close the gap to 1.5°C. Not nearly enough for what is needed to reach the Paris Agreement objectives.

Despite the uncertainty created by the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, revised NDCs demonstrate that the core innovation of the Paris Agreement continues to operate — the obligation to regularly update and strengthen national climate plans to achieve the global goal to maintain climate warming well below 2°C. Over the past decade, successive NDCs rounds have steadily clarified national priorities. And as the latest UNEP Emissions Gap Report confirm, these iterative updates have already shifted the world from a projected 4°C pathway pre-Paris to roughly 2.8°C today. Not yet enough to reach the Paris Agreement objective — but undeniably an improvement driven, at least partly, by the NDCs process itself.

For investors, this is the essential point: Belém did not resolve the ambition gap yet. But it confirmed that the Paris machinery still works amid politically mixed signals, investors still have a roadmap to make climate change investable.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS Even in a politically difficult COP cycle, updated NDCs still offer investors something extremely valuable: a consistent medium-term policy signal. Used correctly, they become a tool for allocation, risk management and engagement — not a diplomatic artefact. Transition and physical climate risks continue amidst political uncertainty It also signals continued policy uncertainty in the near term, so investors should stress-test portfolios against a range of warming scenarios, tighten risk management around carbon-intensive exposures, and maintain active engagement with issuers to push for clearer short- and medium-term decarbonisation plans and credible implementation pathways. |

2. Climate finance: state of play, and a clearer architecture emerging from COP30 through the Baku-to-Belém roadmap

When the 2015 Paris Agreement was signed, climate finance mainly focused on public flows – such as the $100 billion per year target from developed to developing countries by 2020. At that time, according to Climate Policy Initiative, annual private climate finance flows – both domestic and international – were estimated at around $250 and $300 billion overall, $55 to $65 billion coming from commercial financial institutions.

Ten years on, private climate finance now exceeds $1.2 trillion annually, with almost $450 billion coming from financial institutions. Some segments, like renewable-energy infrastructure, have become mainstream across nearly all major markets. Investor mandates have evolved, and climate considerations are increasingly embedded in capital allocation decisions.

Yet progress remains uneven: most private climate finance still flows domestically (over 85% of total global flows), and 2/3 of private international flows are going towards OECD countries and China1. Many emerging markets continue to face structural barriers2 such as high cost of capital, higher risks perceived by investors (e.g. currency risk, political risk), and limited risk-sharing mechanisms. Even though flows to emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) have improved from roughly 5-6% of global climate finance in 2015 to around 10% in 2024, this growth is mainly due to public finance and it is still far below the financing needs.

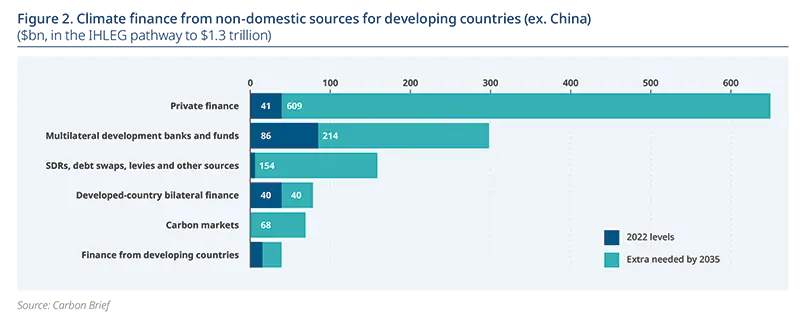

COP30 may mark a turning point: the Baku–Belém Roadmap offers the clearest framework to date for expanding climate finance towards EMDEs, thus being an essential lever to support the implementation of developing countries’ NDCs. The Independent High-Level Expert Group (IHLEG) on Climate Finance estimates that delivering on the Paris targets — including mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage, natural capital and just transition — in EMDEs (excluding China) will require $3.2 trillion per year by 2035. Domestic public and private sources are expected to cover just under $2 trillion; the remaining $1.3 trillion will need to come from international finance, with roughly half from private capital. This means mobilising private climate finance to EMDEs (ex. China) by almost sixteen times compared to today’s flows. During COP30, the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance (NZAOA) committed to supporting the goal to mobilise $1.3 trillion per year in climate finance by 2035.

The Baku-Belém Roadmap does not create new mechanisms, but it consolidates a shared reference architecture for investment in EMDEs structured around five action fronts:

Replenish: significantly increase ‘catalytic capital’ such as grant and concessional finance, particularly for adaptation and loss & damage, which rarely attract private investment.

Rebalance: address debt burdens and f iscal constraints that limit EMDEs’ ability to invest. In parti-cular, it asks MDBs, together with creditor countries and the IMF, to help address fiscal space and debt sustainability in developing countries (including use of innovative debt instruments, debt-for-climate swaps, climate-resilient debt clauses, access to low-cost capital and restructuring).

Rechannel: scale up private finance by expanding blended vehicles, guarantees, and other tools that reduce real and perceived risks — including currency and tenor mismatches, and intensification of MDB’s engagement on climate finance to amplify their catalytic role in providing and mobilizing capital.

Revamp: strengthen domestic capacities and project pipelines, so that more public and private capital can be absorbed and deployed effectively. In particular, it asks MDBs to strengthen capacity and coordination to scale climate portfolios, streamline and de-risk operations, raise internal efficiency (faster review and disbursement cycles), and improve country platforms and coordination across MDBs to deliver at speed and scale.

Reshape: adapt financial rules and frameworks (from credit ratings to capital regulation) to recognize and support climate-aligned investment in EMDEs. This includes carbon markets which is elaborated on in a subsequent section of this paper.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS Even greater opportunities for climate finance - but scrutiny is rising A shift in MDBs’ mandates A potential standardization path for blended finance |

3. Nature & Forests: from small- and medium-scale REDD+3 projects to a dedicated global facility

Nature and forest have become increasingly central in recent COP cycles, moving from a peripheral theme to a core pillar of climate action. Even though COP30 could not land on a language against deforestation, it reflected this shift with the launch of a few initiatives for nature such as the Playbook to Mobilize Private Capital for Nature, jointly led by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), WWF and multilateral development banks. The Playbook provides a system-level framework to scale private investment into nature-positive activities — from standardising project pipelines and improving data and disclosure to deploying de-risking tools and creating investable nature assets. But the biggest achievement of COP30 on forests is undoubtably the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), the first attempt to create a dedicated global financing vehicle to reward countries for conserving their tropical forests.

In 2015, forests were recognized in Article 5 of the Paris Agreement, and REDD+3 provided a UN-recognized mechanism — but no global financing facility existed to reward tropical countries for keeping forests intact. Forest-related finance was limited to bilateral programmes and small REDD+ crediting projects. By 2023–2024, nature-based solutions had become core to climate strategy. Brazil revived Amazon diplomacy, and at COP28 in Dubai two year ago, the idea of a global forest finance mechanism was born. This matured into the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), officially launched at the COP30 Leaders’ Summit.

TFFF is a new long-term finance platform to reward countries that keep their tropical forests standing. It is backed by more than 50 countries that endorsed the launch declaration, including 34 tropical forest countries (covering over 90% of tropical forests in developing countries) and around 20 potential contributors and investor countries.

The TFFF is designed as a large endowment-style vehicle targeting $125 billion. Specifically, around $25 billion of public and philanthropic contributions which are intended to catalyse roughly $100 billion of private investment over time. At launch, governments announced more than $5.5 billion in initial pledges – including $3 billion from Norway and $1 billion each from Brazil and Indonesia, plus commitments or indications of support from other countries. The endowment will be invested on financial markets – a share of the annua returns will then be paid out to forest countries that maintain or increase their forest cover, with at least 20% of the payments earmarked for Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The TFFF is innovative in several ways:

Its scale, mobilizing capital at an order of magnitude never seen before in forest finance, while also helping to strengthen access to capital in emerging countries.

Its focus, effectively turning tropical forest conservation into a long-term, cash-flow generating “nature asset”, using public and philanthropic capital as a first-loss buffer to crowd in private investors, and a pay-for-performance model (payments are conditional on verified forest conservation).

A concrete example. It is co-designed by major forest countries rather than traditional donors, making it a concrete example of a nature and climate finance project from developed to developing countries rather than an ambitious but aspiring pledge.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS Nature finance is scaling New vehicles are emerging |

4. Adaptation & Loss-and-Damage: resilience becomes investable

Loss and Damage – referring to the negative effects of climate change that occur despite mitigation and adaptation efforts – was politically recognized in Article 8 of the Paris Agreement but the text explicitly precluded any interpretation involving liability or compensation. Support was limited to the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM), created in 2013 and focused on knowledge-sharing — not funding.

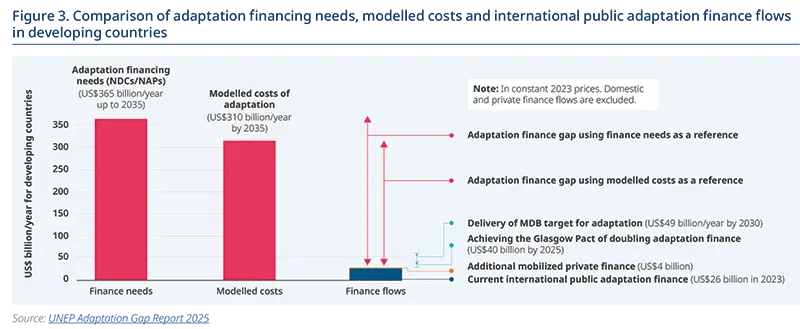

Adaptation finance has slowly been gaining traction: the Glasgow commitment to double adaptation finance by 2025 increased flows, though they remain far below what is needed. According to UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report 2025, developing countries will require $310–365 billion per year by 2035 to implement priority adaptation actions identified in their NDCs and NAPs. Current international public adaptation finance flows amount to only $26 billion in 2023, down from 2022, leaving an annual adaptation finance gap of $284–339 billion through 2035 — a gap that is 12–14 times current flows.

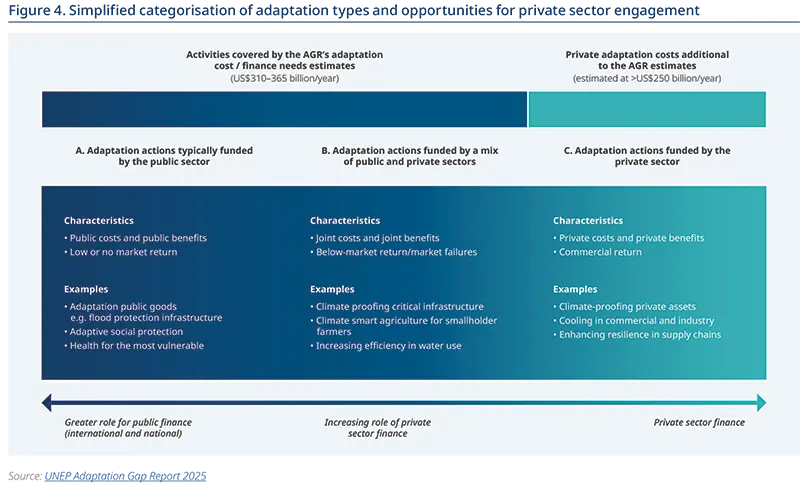

For investors, this widening gap signals a large and growing market for adaptation solutions and resilience finance. UNEP estimates that the private sector could realistically contribute $50 billion per year by 2035, mainly in upper-middle income countries where private finance could represent up to 22% of adaptation needs vs. only 4% in low-income countries. This represents a tenfold increase from the ~$5 billion in tracked private adaptation finance today.

After years of pressure from vulnerable countries, momentum for Loss and Damage grew. COP26 in 2021 saw the launch of the “Glasgow Dialogue” on funding arrangements. The breakthrough came at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh the year after, with the creation of a Loss and Damage Fund (LDF). By 2024–2025, the Board, Secretariat and trustee arrangements were in place. In Belém, the Loss and Damage Fund showed it was becoming operational, with a first call for proposals: around $250 million available for pilot projects — the first tangible disbursement mechanism. This marks the transition from concept to delivery.

Even though Loss & Damage finance remains primarily intergovernmental, the implications for investors might become significant, with needs estimated at more than $310 billion annually by 2035 by the UN Environment Program:

Physical climate risk is now financially material: the existence of a dedicated fund signals that catastrophic losses are systemic, not exceptional. This strengthens the rationale for integrating physical-risk analysis across sovereign, infrastructure and corporate exposures.

Fiscal and regulatory shifts are likely: proposals for aviation levies, shipping fuel levies, or windfall taxes on fossil profits as funding sources for L&D mechanisms may gain traction. This could affect sector profitability and long-term valuations.

Growth of resilience finance: parametric insurance, catastrophe bonds, resilience-linked loans and “climate resilience bonds” are likely to expand, supported by MDBs and philanthropic capital.

Sovereign-risk differentiation: rating agencies and IFIs may increasingly incorporate vulnerability and resilience metrics into sovereign credit assessments.

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS Climate adaptation and loss & damage finance is scaling Risk landscape is altered and should be embedded into financial analysis Issuers adaptation strategies ever more material |

5. Carbon Markets: standardization still underway

In 2015, carbon markets were more of a promise than a functioning system. Before and since the Paris Agreement, they have largely developed in parallel, with limited linkage and uneven integrity standards. It was not until COP26 in 2021 in Glasgow that the core Article 6 rulebook was finally adopted: it set out basics on corresponding adjustments, a new UN mechanism (Article 6.4), and safeguards against double counting. COP27 and COP28 filled in some technical parameters, and COP29 in Baku last year completed the remaining guidance, finalising the rulebook for Article 6.

Negotiations in Belém focused on implementation issues such as permanence requirements for land-based removals and safeguards against weakening integrity. Some countries pushed for greater flexibility for nature-based credits; many others — including NGOs — warned against diluting standards or allowing offsets to substitute for domestic action.

Three main developments around COP30 can be highlighted:

A new international coalition for compliance carbon markets: Brazil launched an Open Coalition on Compliance Carbon Markets bringing together 18 parties (EU, UK, Canada, Germany, France, China, Singapore, Norway…). The goal: harmonizing monitoring, reporting and verification, exchanging best practices, and eventually linking Emissions Trading Systems (ETS) to create a more liquid and predictable compliance market.

More bilateral Article 6.2 deals: Indonesia–Norway concluded an agreement to transfer credits from renewable projects. Brazil advanced talks with Switzerland and Singapore. These early ITMO transactions are turning Article 6 from architecture into real-world deals.

EU signalling a limited return to international credits: Ahead of COP30, the EU announced a –90% climate target by 2040 and authorized limited use of international credits (up to 5% of reductions).

IMPLICATIONS FOR INVESTORS Carbon markets are expanding rapidly, and unlock additional funding: countries use compliance carbon markets, while companies increasingly make use of voluntary carbon markets, buying carbon credits. As both carbon markets expand, convergence between them could significantly benefit climate mitigation actions. High-integrity carbon markets are an essential tool for reaching net zero emissions. Belém signals that Article 6 is moving into early implementation, while outside the UNFCCC, a new diplomatic architecture is forming — coalitions and linkages — that could shape future price signals and liquidity.

Due diligence and monitoring on the agenda |

Conclusion

Ten years after the Paris Agreement, and despite geopolitical volatility, COP30 confirmed that climate action is not only driven by negotiation cycles but also by tangible implementation and capital flows: investments in renewables are still double those of fossil fuels since last year, displaying technological progress and the viability of low-carbon alternatives. Being the second most attended COP (after COP28 in Dubaï), Belém fell short of the expectations of some stakeholders. However it clarified the trajectory for the decade ahead: it projected a decade in which climate governance will be more fragmented, implementation-driven, and heavily reliant on private capital.

That imperative plays out against a challenging political backdrop. Investors must demonstrate alignment with their fiduciary duties, measurable impact, maintain integrity, and innovate in structuring. More large-scale instruments and de-risking structures are needed to translate ambition into capital flows.

Finally, COP30 highlighted a rebalancing of leadership towards emerging markets and developing economies. This shift will require investors to adapt geographic exposure, risk frameworks and engagement strategies, and to combine commercial discipline with local partnerships and bespoke instruments. For investors, it means that despite political uncertainty, expectations remain clear: translating these signals into capital allocations — across mitigation, adaptation, nature and resilience — will be decisive for the decade ahead.

- Approximate figures obtained from Climate Policy Initiative data: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2025/

- Read more about these structural barriers in the paper recently published on Amundi Research Center How can investors lean into blended finance structures: demystifying credit enhancements

- The acronym REDD+ stands for “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation and the Role of Conservation, Sustainable Management of Forests and Enhancement of Forest Carbon Stocks in Developing Countries”

With the contributions of:

Angge Roncal Bazan, Responsible Investment Specialist – Development Finance Lead, Amundi

Théophile Tixier, Responsible Investment Specialist – Net Zero Development Lead, Amundi

With the support of:

Marine Braud, founding partner at Alameda Sustainability Advisory.