Summary

Context: Stablecoins combine the efficiency of blockchain with the stability of fiat currency, marking a potential revolution in global payment systems. With the recent passage of the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act, the US has signalled a clear regulatory support for the monetary innovation that could accelerate the mainstream adoption of stablecoins and reshape the financial landscape. Macro implications: Widespread adoption of stablecoins could alter the transmission of monetary policy, shift demand for Treasury securities, and reinforce the global dominance of the US dollar (as issuers are forced to hold USD cash or USD equivalents as collateral). While the direct impact on economic output may be limited, second-order effects on interest rates, capital flows, and financial stability could be profound. Risks and vulnerabilities: Stablecoins remain exposed to counterparty, collateral, and systemic risks, given their reliance on private issuers and a technology infrastructure with an unproven track record in handling mass transactions. In extreme scenarios, collateral mismanagement, capital flight, cyberattacks, or insufficient regulatory oversight could undermine confidence and trigger financial instability with global spillovers. |

By combining the payment efficiency of blockchain technology with the value stability derived from being pegged to the world’s reserve currency (USD), stablecoins have emerged as a monetary invention that some believe could revolutionise the financial world. While other countries are promoting stablecoins denominated in their own currencies, the recent passing of the GENIUS Act marks a major milestone: it represents an explicit endorsement from the US government that could push stablecoin development and adoption into high gear.

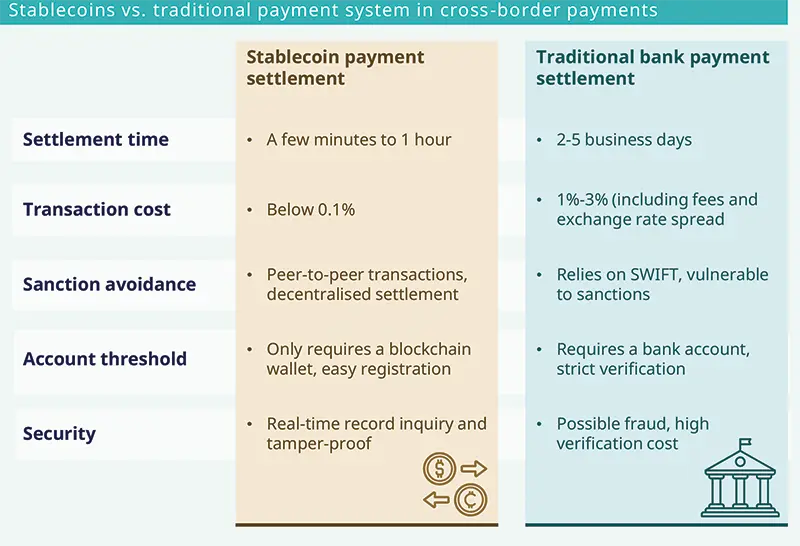

Despite enthusiasm from corners of Wall Street, debates abound on whether the cryptocurrency can live up to its full potential. As a means of payment, stablecoins have a clear advantage in terms of cost, speed, and efficiency, over the existing bank-based system that can be particularly clumsy in cross-border transactions — stablecoins have great potential to gain market share at the expense of banks and their SWIFT networks.

However, the gains in payment efficiency must be weighed against the opportunity costs of using stablecoins, which generally do not pay interest when held directly*. In addition, while fiat currency is backed by sovereign credit and central banks with ‘unlimited’ printing machines, stablecoins are instead issued by private companies, making them more prone to counterparty risks.

Wider adoption of stablecoins could pose challenges for regulators managing risks of illicit activities (e.g. money laundering and tax evasion), bank failures (as money leaves the system), and monetary policy (with large capital flows complicating the central bank’s ability to control the yield curve and the economy).

While stablecoins may offer support to the US government by creating new demand for Treasury securities and furthering the USD’s reign in global markets, other countries may have to deal with more erratic capital flows, less control of their own financial systems and risks of re-dollarisation. These financial and geopolitical ramifications may have underscored a more cautious approach towards stablecoins by China and the EU thus far.

*Some exchanges (e.g., Coinbase) currently offer yields of around 4-5% on stablecoin deposits. These returns arise not from stablecoin itself, but from lending activity conducted by the platform. Banks have lobbied regulators to restrict such practices, citing risks of bank runs and erosion of their deposit base.

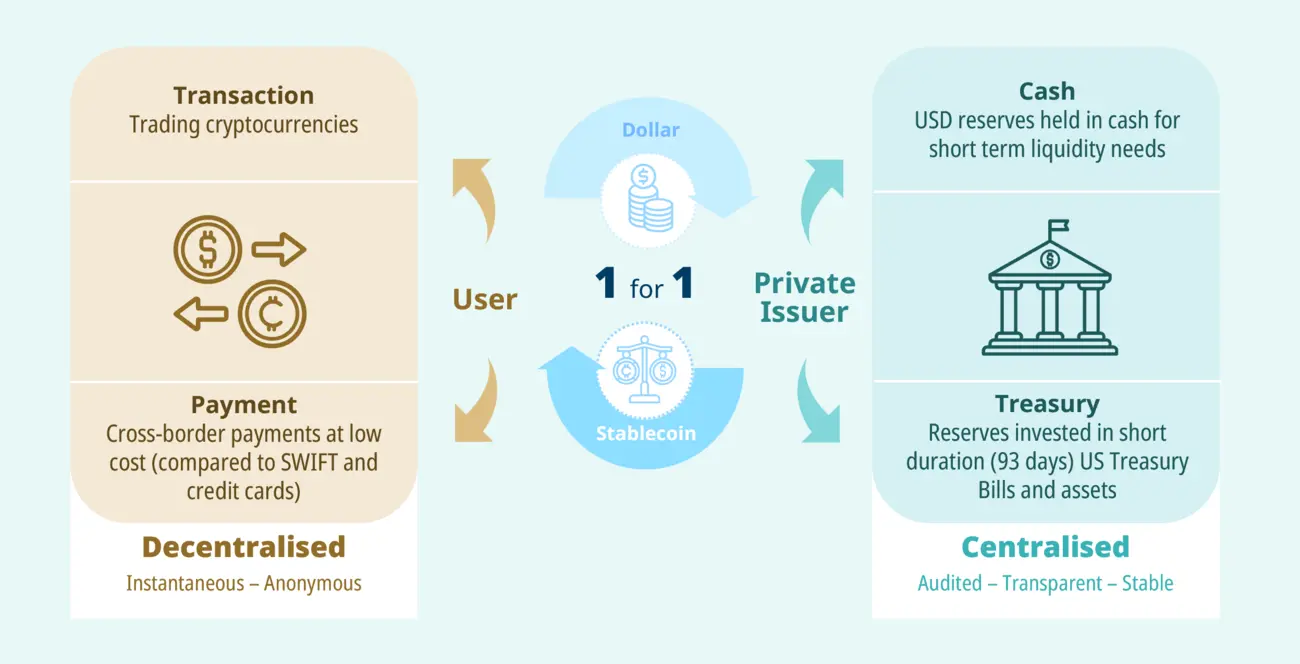

Stablecoins extract stability by maintaining a 1:1 peg to a commonly-used fiat currency.

What is a stablecoin?

Stablecoins carry two essential features:

First, as a type of cryptocurrency, stablecoins are built on blockchain technology, enabling faster, cheaper, more secure, and decentralised transactions than the existing architecture built around banks permits — advantages particularly beneficial for cross-border payments and transactions.

Second, stablecoins are ‘stable’ in value, as they maintain a 1:1 peg to a commonly-used fiat currency (e.g. USD), making them better suited as a medium of exchange. This contrasts with other cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoins, whose value can fluctuate wildly due to speculative trading.

How does it work?

Stablecoins are transacted between issuers and users, with subsequent activities to help ensure that the instrument functions as a stable transactional medium.

How stablecoins work

Stablecoin User deposits a specific amount of fiat currency (e.g. USD) with a stablecoin issuer. This deposit (or reserve) serves as the backing for the stablecoins issued.

Stablecoin Issuer, in return, creates the stablecoins at a 1:1 ratio to the deposited USD. Under the GENIUS Act, only private-sector companies are allowed to issue stablecoins; USD Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) dominate the space currently. US government entities, including the Fed, are barred from issuing digital currencies at present.

Reserve Management: To maintain the 1:1 peg between stablecoins and the USD, the issuer invests the deposited funds in highly liquid and low-risk financial assets, including cash, bank deposits, and short-term Treasury securities. Under the GENIUS Act, reserve management is subject to regular and strict auditing by regulators, making this part of the system effectively ‘centralised’.

Stablecoin usage: Once issued, the stablecoins can be used on the blockchain, which provides instantaneous and point-to-point transactions between (potentially) anonymous parties. The ‘decentralised’ nature of this technology is (still) preserved, for now.

Redeemability: When users redeem their stablecoins, the issuers return the USD at a 1-to-1 ratio and destroy the returned cryptocurrencies.

It’s important to note that, under the GENIUS Act, stablecoin users are not remunerated with interest when simply holding the cryptocurrency, although some exchanges (e.g. Coinbase) currently offer yields on stablecoin deposits. This is designed to emphasise stablecoins as a payment instrument, not an investment asset. Issuers, on the other hand, pocket all interest gains by holding reserves in interest-bearing assets. Therefore, stablecoin users must weigh the convenience of using blockchain for transactions and the cost of forgoing interest earnings.

Why have stablecoins become popular?

Examining the supply, demand, regulation, and user cases of stablecoins highlights the appeal of the payment system.

Once the technical infrastructure is established, issuers face practically zero marginal cost to produce the cryptocurrency. The revenue they generate (by investing reserves in interest-bearing assets) grows with the size of their supply. Hence, so long as short-term interest rates stay above zero (in fact they are at near post-GFC highs in the US) issuers would want to issue as many stablecoins as possible. The real constraint for growth of the market, therefore, lies with demand.

The following table provides a comparison between stablecoins and the existing SWIFT-based system in cross-border transactions.

The passing of the GENIUS Act has been seen as an official endorsement for the development of stablecoins in the US. This improved regulatory clarity has given skeptical institutions (and end-users) the needed confidence in the technology, accelerating public awareness and the adoption of the new payment system.

Stablecoins are commonly used by cryptocurrencies traders and DeFi operators to hold ‘idle cash’ in their crypto accounts. As the Bitcoin market has grown exponentially, so has demand for ‘liquidity’.

In addition, the decentralised, anonymous, and unregulated nature of the blockchain system also makes it ideal for financing illegal activities, such as money laundry and drug trafficking. Stablecoins might have taken market share from other transaction mediums, fiat or crypto, fueling growth of their usage in recent years.

The stablecoin industry has grown dramatically, from less than $2 billion in 2019 to near $250 billion now.

Where has it been and where is it headed?

Past: The stablecoin industry has grown from less than $2 billion in 2019 to more than $250 billion now. The total volume of transactions reached $28 trillion last year.

Present: The stablecoin market has gained significant momentum this year, following the regulatory changes in the US. High-profile global corporations — in traditional finance (JPM, Citi), fintech (PayPal, Ant), e-commerce (Amazon, Alibaba, JD.com, Alibaba), and brick-and-mortar retail (Walmart) — are all entering the market, actively developing and launching new stablecoin initiatives.

Future: Opinions vary as to what lies ahead for stablecoins:

On the skeptical side, the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) warns that stablecoins lack of a perfect 1-to-1 peg due to potential mismanagement of reserves. The lack of adjustment flexibility on the supply side also makes it an imperfect substitute to fiat currency. The BIS argues that these shortcomings will limit stablecoin’s growth and reliability as a foundation for the monetary system.

Views from private-sector institutions are generally more sanguine. JPM expects the stablecoin market to double in size by 2028. Citigroup projects the market to reach $1.6-3.7 trillion by 2028 (in their base and bull cases respectively).

The most optimistic forecasts are from Ripple and Boston Consulting Group, expecting the stablecoin market to top $2.4 trillion by 2028, $4.8 trillion by 2030, and $9 trillion by 2033.

Macro implications: (discussions below focus on directional changes, while the scale of impact will be determined by the eventual size of the market) Economy: the direct (first-order) impact on the economy should be minimal. Stablecoins merely replace existing fiat currencies already in circulation, and their issuance does not involve new monetary or credit creation. The improvement in payment efficiency may marginally lift economic growth, while the second-round effect via lower interest rates (see below) could be more significant. Banks: could be hurt if stablecoins succeed in developing an alternative payment system. Liquidity could be drained from traditional banks, posing a challenge to financial stability. Small regional banks are more vulnerable, while larger banks, such as JPM, are developing their own (deposit-based) digital tokens to compete with Tether and Circle. Monetary policy: as there is no money or credit creation, stablecoins will unlikely affect the aggregate monetary supply or the credit cycle. However, as the user base of stablecoins — which typically do not pay interest when held directly — expands, the economy’s sensitivity to interest rates could decline, potentially hampering the transmission of monetary policy. Moreover, increasing the buying/selling of short-term Treasuries related to stablecoins may challenge the Fed’s ability to control the short-end of the yield curve. Markets: a rapid adoption of stablecoins, under the 1-for-1 collateral requirement, will increase demand for Treasury securities, setting off a chain of effects, all else being equal. Lower interest rates will be a boon for the economy. Greater buying of short-term Treasuries may steepen the yield curve. Cheaper debt financing will ease financial constraint for the government but may exacerbate fiscal exuberance down the road. Finally, a greater adoption of USD stablecoins globally will keep the US dollar (needed to convert to stablecoins) central. Global spillover: the USD stablecoins have a natural advantage of being pegged to the world’s reserve currency. Small countries, with volatile currencies, high inflation and less credible central banks, may cede control of their monetary systems if the public flocks to USD stablecoins. Countries, with capital account controls, may also be challenged by unregulated flows that erode the efficacy of those restrictions. The rise of USD stablecoins could marginalise the use of other fiat currencies, leading to re-dollarisation that extends the dollar’s hegemony in the global system. Geopolitics: sanctions on the global SWIFT system have been imposed on Russia and Iran and threatened against China by the US. Wider adoption of stablecoins may render such sanctions less effective, as decentralised blockchain technology enables users to conduct point-to-point transactions, bypassing the SWIFT system. |

The risk, however, is that when mismanagement occurs in regulators’ blind spots, small issues can snowball into systemic crises.

What could go wrong?

Counterparty risks: Stablecoin issuers are private companies, without the backing of sovereign governments, central banks, or official deposit insurance guarantee (e.g. from the FDIC). Theoretically, so long as issuers manage reserves properly, by maintaining the 1:1 collateral ratio and holding reserves in the safest and most illiquid assets, the system should function as desired.

The risk, however, is that when mismanagement occurs in regulators’ blind spots, small issues can snowball into systemic crises. A sudden exodus of capital could overwhelm issuers’ ability to redeem stablecoins, collapsing the system and shattering confidence in the entire infrastructure.

Collateral risks: Stablecoins are worth only what their underlying collaterals are worth. The nominal peg to the USD will not save stablecoin users from losing real purchasing power if the value of collateralised assets decline due to dollar depreciation, rising inflation, or the US government restructuring its debt in extreme circumstances.

Financial stability risks: The rise of an alternative payment system could trigger a multitude of capital flows that pose financial stability risks within a country and globally. As users ditch banks for stablecoins, a capital flight from the banking system could pose a challenge, particularly for small institutions.

Financial regulation will, therefore, need to be recalibrated to guard against these risks.* More broadly, traditional and digital financial infrastructures could be challenged, requiring monetary policy to adapt to a potentially less interest-rate-sensitive economy and more stablecoin-sensitive yield curve. A wider adoption of USD stablecoins will diminish the use of other fiat currencies, exacerbating global (financial and real) imbalances and deepening macro/geopolitical risks.

Integrity risks: The decentralised and unregulated nature of blockchain technology makes it easy for stablecoin users to conceal profits or conduct undeclared transactions. The inability to properly monitor, track, and supervise transactions by regulators and law enforcement agencies could give rise to more tax evasion, money laundering, and other illegal activities.

System risks: A large-scale cyberattack or shutdown of critical computing infrastructure could severely disrupt the crypto ecosystem. While centralised issuers can mitigate certain risks by, for example, blacklisting stolen tokens, the systemic vulnerabilities of blockchain-based networks remain.

In such a scenario, stablecoin transactions might slow down, and in extreme cases, halt entirely. This disruption would undermine the usability and trust in the system.

Technology risks: Quantum computing may pose a future risk to blockchain security. While still in its infancy, experts estimate these frontier technologies could be able to hack wallets and compromise the network if blockchain does not keep up with its security protection.

*Similar vulnerabilities exist in the traditional financial system, though the transmission channels differ.