Summary

Instead of pushing cryptocurrencies to the sidelines, policymakers are now looking for ways to safely integrate them into the broader financial system.

Regulation paves way for big changes in crypto

The digital asset landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, partly due to regulatory shifts that are lowering some of the barriers that previously deterred regulated financial institutions from entering the market. After years of being dominated by retail investors and early adopters, institutional interest in crypto assets is now emerging and has the potential to shape how the ecosystem matures, as well as how its credibility evolves.

For a long time, crypto operated in a grey zone, with policies that were either vague or focused mainly on enforcement. Such uncertainty made it difficult for banks, asset managers, and other traditional financial institutions to participate. Now, instead of pushing crypto to the sidelines, policymakers are looking for ways to safely integrate it into the broader financial system.

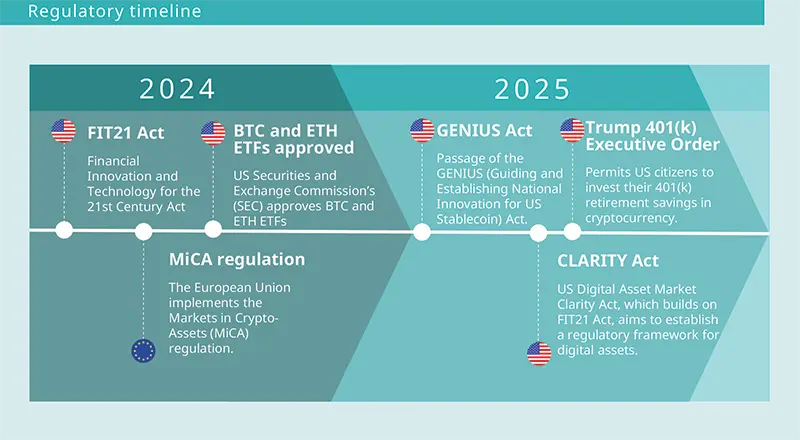

The United States has been a prime mover on this front. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which was initially aggressive in classifying most crypto assets as securities, softened its stance after losing pivotal cases in 2023 and early 2024. Since then, two important pieces of legislation have laid out clearer definitions of what constitutes a security rather than a commodity, which makes regulation more straightforward. Bitcoin and Ethereum, for instance, are likely to remain under the oversight of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) since they meet key criteria for decentralisation – such as the absence of a single issuer or affiliated party controlling more than a fifth of the asset or its governance. Conversely, tokens that are built on less decentralised infrastructures will be assessed case by case but are likely to be treated as securities and fall under the SEC’s jurisdiction.

There is also a clearer treatment of stablecoins, which are digital tokens that are typically pegged 1:1 against fiat currencies such as the US dollar. In January 2025, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order barring US federal agencies from developing or promoting a central bank digital currency (CBDC). This signalled support for privately issued, dollar-backed stablecoins as a free-market alternative. The message was clear: network adoption and market-driven innovation will be more important than centralised control in shaping the future of digital money.

As more guardrails are established globally, institutional capital is likely to continue to flow into digital assets.

This approach was reinforced in July 2025 with the passage of the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act. The law, which represents a significant step towards regulatory clarity and offers customers more protection; requires issuers to fully back stablecoins with high-quality liquid assets, such as cash and Treasuries; comply with strict redemption and transparency standards and bans algorithmic models that might generate instability.

By legitimizing and regulating these instruments, the law enhances the credibility of stablecoins and provides a clearer path for institutional engagement at a time when the Federal Reserve has changed guidance that had in the past effectively discouraged regulated banks from engaging in crypto activities. Now, banks can explore tokenisation and consider integrating digital assets into their custodial and payments systems, with the potential to contribute to further growth. Moreover, an executive order in August 2025, granted 401 (k) retirement accounts in the US full access to crypto and other alternative assets, unlocking a new pool of capital for digital assets.

The United States is not alone in this shift. The European Union is implementing the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation, a comprehensive framework that standardises rules across member states and grants legal certainty to firms operating in this space. By reducing regulatory fragmentation and offering legal clarity, this regulation is expected to spur innovation and encourage fintech and blockchain firms to expand their presence within the EU.

Authorities in the UK, Asia, and Latin America are also moving towards combining innovation-friendly policies with stronger consumer protection. As more guardrails are established globally, institutional capital is likely to continue to flow into digital assets, giving the market more stability and opening up new opportunities for both retail and professional investors.

Growth of institutional interest in cryptocurrencies

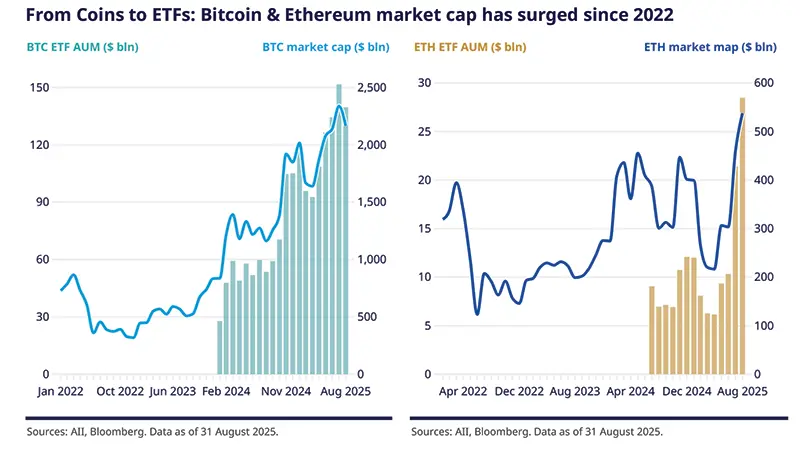

After years of hype led primarily by retail investors, the digital asset market has entered a new era defined by the strategic and large-scale entrance of institutional capital, which could contribute to the maturity, scale, and credibility of the crypto ecosystem. Given digital assets represent only around 1.5% of the Global Liquid Market Portfolio, even modest shifts in demand could lead to substantial growth as infrastructure improves and confidence in the technology grows.

Already, banks and custodians including JPMorgan, Citi, HSBC, State Street, and UBS are launching initiatives on various fronts, such as custody, tokenised deposits, and settlement platforms, which could power global finance on blockchain infrastructure.

Meanwhile asset managers are launching tokenised funds and Crypto Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) and are integrating digital assets in core portfolios. This is providing traditional investors with easy access to digital markets and seems consistent with the increased demand from family offices and high-net-worth individuals, who seek customised digital exposure as part of their broader wealth strategies.

Another key development is the emerging debate about whether central banks and sovereign wealth funds should hold Bitcoin or major digital assets as part of a diversified reserve strategy. The concept, which remains controversial, has been inspired by the way countries manage gold reserves. It reflects a growing acceptance of the asset class and points to its potential strategic importance in the financial infrastructure in the future.

As institutional adoption picks up, the focus is shifting to how the full potential of digital assets could be unlocked and what role they might have in portfolios. It is therefore important to understand how and why the value of such assets moves. While cryptocurrencies have often been viewed as a single asset class, their behaviour – relative to either traditional financial assets or each other – has changed over time and reveals a more nuanced picture.

Before 2020, there was a high degree of correlation between major tokens in the crypto universe, but they generally displayed little correlation with traditional assets. In the past five years, they started tracking market sentiment more closely and over the short term, for example over weeks or months, have tended to move more in synch with risky assets, such as technology stocks or high-yield credit.

This has led some to question the extent to which they can help investors diversify their portfolios. However, such correlations may largely be a symptom of crypto’s early and speculative phase when sentiment and liquidity conditions drive the majority of price action. Also, correlation studies indicate that over the long term, co-movement between cryptocurrencies and risky assets diminishes after controlling for macroeconomic shocks or periods of market stress. Bitcoin’s correlation with equities, for instance, tends to weaken outside of risk-off periods, indicating its role may evolve as the asset class matures and adoption deepens across different investor types and geographies.

The diversity of cryptocurrencies

| ||

|

| |

| ||

Bitcoin: potential collateral and a tool for treasury management

Bitcoin (BTC) has solidified its position as the dominant cryptocurrency, with its market cap reaching approximately $2.3 trillion and its market share of the sector, known in the industry as market dominance, has risen to more than 60% by July 2025. This is largely explained by macroeconomic dynamics, its unique position as a decentralised monetary asset and substantial institutional investments in the asset, particularly following the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) approval in January 2024 of spot Bitcoin ETFs.

Bitcoin is gradually being viewed less as a speculative technical experiment and more as a monetary tool for the digital age, which might be able to help promote stability in the face of rising global debt and inflation. For example, some investors view Bitcoin as a digital version of gold, with the long-term potential to be used as collateral, or as a reserve asset underpinning fiat-currency-based monetary systems (in the same way that gold backed the US dollar under the Bretton Woods system).

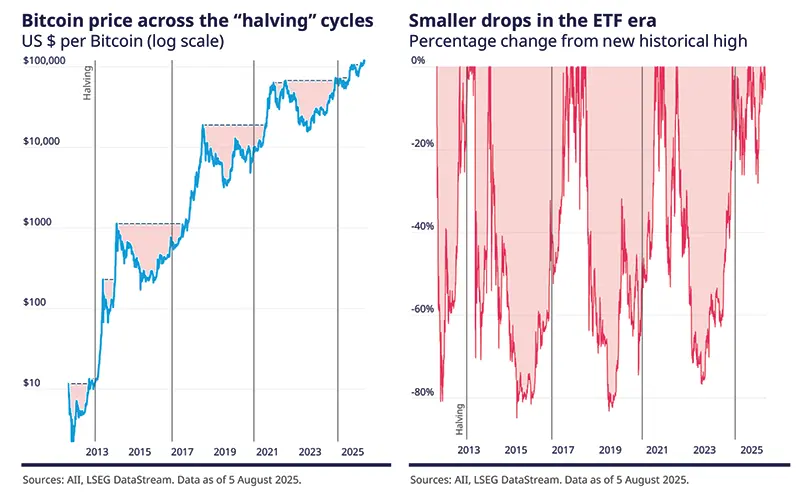

While it is unclear whether this will be the case, the macroeconomic and geopolitical shifts that are underway will test whether some of the properties often ascribed to Bitcoin will hold true. The growing risks to global funding, the concerns over monetary debasement, fiscal dominance, capital controls, and sanctions are reflected in the recent surge in the price of gold, which hit a record high above $3,500 in September 2025. These worries should also fuel demand for Bitcoin if the analogy were to hold. Gold has earned its reputation as a safe haven and store of value over thousands of years, but the appetite for a digital asset, such as Bitcoin, could gradually increase as the global economy becomes more digital. The supply of both gold and Bitcoin is constrained, in theory independently of any country’s action. But Bitcoin is easier to divide, with the smallest unit, 1 Satoshi, equivalent to 0.00000001 BTC. The token is also portable and relies on a programmable, secure and fully decentralized network. New Bitcoins are created through mining, with rewards given to miners for each block added to the chain. A block is mined approximately every 10 minutes, which allows high-frequency audits of the entire process, while the rewards for creating a block (i.e. new Bitcoins) are halved approximately every four years (or every 210,000 blocks)1. This mechanism, called “Bitcoin halving”, will continue until rewards become negligible, which is estimated to happen around 2140, and is designed to ensure that the maximum supply of Bitcoin never exceeds 21 million.

While mining concentration and rapid technological advancements, such as quantum computing, may be risks, some public and private companies as well as other institutions, are progressively adopting treasury management strategies that use Bitcoin, known as Bitcoin Treasury Strategies. As of July 2025 there are more than 150 public companies that hold Bitcoin on their balance sheets, and together they own more than 4.5% of the overall Bitcoin supply that will ever exist – that is, 21 million Bitcoins. If more than 90% of the sample is listed in the United States, Bitcoin treasury strategies may soon pave the way for new methods to manage corporate liquidity.

The altcoin ecosystem: Ethereum and programmable blockchains

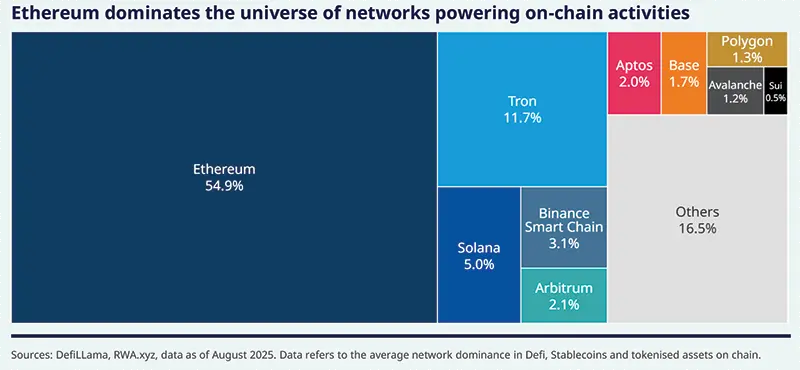

Altcoins, short for alternative coins, refer to all cryptocurrencies other than Bitcoin. They were developed as alternatives to the latter, often aiming to improve its perceived limitations, such as scalability, transaction speed and consensus mechanisms2. Altcoins include a wide range of projects, of which programmable blockchains represent foundational layers. Blockchain networks such as Ethereum allow developers to write and deploy smart contracts, self-executing code that trigger operations without the need for centralised control, which are vital to enable decentralised applications (dApps).

At the core of programmable blockchains are “utility tokens”, which serve as the network’s “digital oil”. They are essential to pay transaction (gas) fees, to deploy and interact with smart contracts and to secure the blockchain through staking. Ether (ETH), for instance, is the native utility token of the Ethereum blockchain and is essential to run the network3.

While utility tokens power programmable blockchains, various tokens can be issued by decentralised applications or protocols. This layered structure defines the altcoin universe, and in this hierarchy, base-layer tokens (digital oil) are indispensable for the network, while application-layer tokens are needed to interact with or govern specific decentralised applications running atop those networks.

Applications are diverse and include decentralised lending, borrowing and trading (known as DeFi, or decentralised finance); non-fungible tokens (NFTs), such as digital collectibles, currently used in identity, gaming and loyalty programmes; and traceability in logistics and supply chain management.

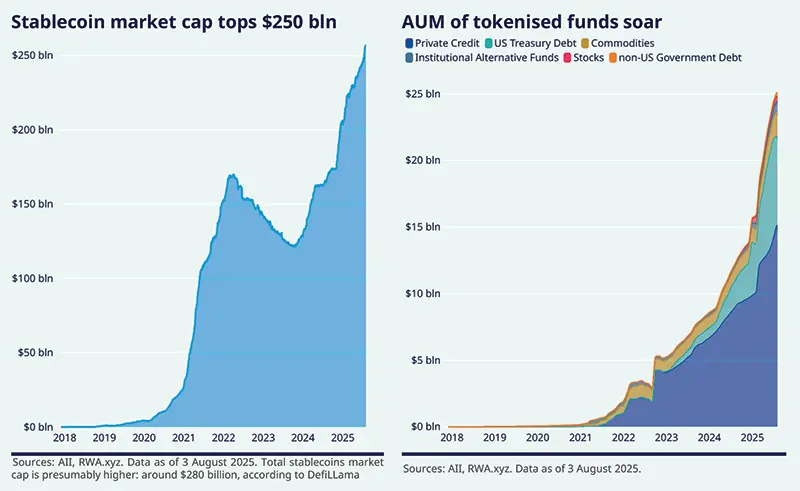

They also facilitate asset tokenisation4, which is emerging as a potentially significant trend in the asset management industry since it facilitates easy transfers and the division of ownership. The value of digital tokens, which mirror traditional financial assets but which, for now, stop short of transferring a legal title, known as on-chain Real World Assets (RWA), exceeded $25 billion in July 20255, with tokenised private credit and US treasury funds accounting for a significant share. While counterparty risk remains and smart contracts need stricter control, their integration with platforms that are designed for crypto assets is growing fast. Tokenised treasury funds, for instance, are now being accepted as collateral in platforms that are designed for crypto assets and have the potential to enable borrowing and trading against a real-world, low-risk asset. Unlike stablecoins, which offer no yields, and volatile assets like Bitcoin and Ethereum, tokenised treasury funds deliver both stability and returns, creating a collateral base that earns while it is deployed.

Ethereum (ETH) still benefits from first-mover advantage and is the dominant network for most applications. However, its market share had declined to 13% by August 2025 from 21% in December 2021. Huge volatility in its price this year has also stoked concerns. Limited volumes in Web3, DeFi and NFTs explain part of the issue, but competition from alternative blockchains is also growing rapidly. Challengers such as Solana, BNB Chain, Ripple, Tron, and Avalanche are innovating, offering lower fees and improving the user experience. A multichain ecosystem is most likely in the future, with interoperability and specialization driving adoption and innovation. The eventual winners will be those who do the best when it comes to scalability, security, usability and adaptability to changing regulatory frameworks.

Integrating blockchain solutions with existing legacy systems remains complex and many companies continue to struggle with the technical and operational challenges. But regulatory clarity and standards of adoption will likely make core infrastructure more robust and help institutional interest to develop, in our view.

Stablecoins: the race for payment networks

Stablecoins are designed to maintain price stability because of their 1:1 link with fiat currencies such as the dollar. They offer programmability, a low-cost structure, and the speed of blockchain technology.

Their use in cross-border payments is growing and they are emerging as key players in the digital ecosystem. The total market capitalisation of stablecoins exceeded $280 billion in August 20256, transaction volumes are growing at double-digit rates compared with a year earlier, and digital payments are becoming a strategic priority for countries given the new financial architecture that is developing at a global level.

The current US administration has, as previously outlined, signalled support for privately-issued stablecoins, rather than developing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), with the GENIUS Act providing strategic endorsement of US dollar-backed solutions. This legislative move likely serves two critical strategic objectives: preserving US dollar dominance in the digital era and deepening demand for US public debt.

On the first count, the US dollar is set as the default currency of choice in the digital financial architecture in a pre-emptive response to accelerating geoeconomic realignments, notably China’s push to establish an alternative to SWIFT. On the second point, regulated stablecoin issuers have the potential to become steady, marginal buyers of short-term US government debt and might help to smooth funding pressure over time.

Stablecoins are no longer a crypto-only game USD Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) dominate the space but have notable differences when it comes to market reach and positioning. USDT, issued by Tether, is the largest stablecoin by market capitalisation and trading volumes. It is well integrated across exchanges and decentralised finance (Defi) protocols, has broad blockchain interoperability and benefits from strong penetration in offshore and emerging markets. USDC, issued by Circle, is fostering institutional adoption via a strong compliance framework and transparent reserve attestations, but has struggled to close the gap, at least until recently7. The use of stablecoins continues to expand in cross-border payments, retail-prepaid accounts management and the tokenisation of real assets, which exceeded $25 billion in August 2025. Both Visa and Mastercard can currently settle stablecoin transactions with selected partners (they are focusing on integration, interoperability and compliance frameworks only), while new entrants like PayPal are already offering their own stablecoin (PYUSD) and seek to leverage their integration with payment rails to gain market share. Regulatory advancements mean there are likely to be more new issuers, perhaps paving the way for large consumer platforms that have existing user ecosystems, such as Amazon, Apple or Starbucks, to issue their own US dollar-backed stablecoin. |

Hundreds of crypto projects fail annually due to mismanagement and fraudulent behaviour.

Key risks linked to cryptocurrencies

While regulatory efforts are trying to bring structure and oversight to the market, a range of inherent vulnerabilities remains embedded in the design, operation, and adoption of cryptocurrencies. These risks vary substantially across the various crypto assets and range from environmental sustainability and technological threats, to governance fragility, regulatory exposure and the risk of capital loss given the potential for projects to fail.

entration similarly translates into disproportionate governance control. Large liquidity providers, which are usually run by a corporation or invited partners, can shape protocol decisions and censor activity. Centralisation may be common in traditional web/cloud architecture, with firms like Amazon (AWS), Microsoft (Azure), and Google (GCP) hosting large portions of internet infrastructure, but these companies operate under service-level agreements, brands, and regulatory oversight, which do not apply to most crypto projects today.

Energy and climate concerns are more acute for Bitcoin and older Proof-Of-Work (PoW) altcoins, like Litecoin, but are virtually negligible for modern Proof-Of-Stake (PoS)8 platforms and stablecoins. This difference across cryptocurrencies stems from the different consensus mechanisms that govern their blockchains. In PoW blockchains, such as Bitcoin, miners compete to solve complex mathematical puzzles that require powerful hardware and a vast amount of electricity.

According to the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI), the Bitcoin network currently consumes around 200 TWh9 annually, more than the annual consumption of countries such as Poland or Argentina. Pressure on the industry to embrace sustainable energy solutions and reduce reliance on fossil fuels is therefore likely to grow.

That said, Bitcoin energy consumption remains low relative to other energy-intensive industries. Bitcoin mining currently accounts for less than 0.3% of global energy consumption and 0.8% of global electricity consumption. While it consumes 1.55 times more electricity than gold mining and slightly more than current AI infrastructure, it uses substantially less than the iron, steel, and chemical sectors.

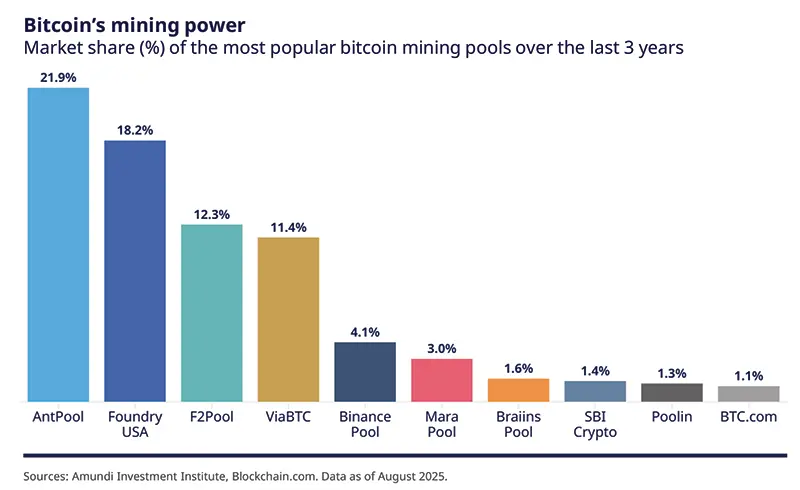

Bitcoin mining power concentration is high: the US share of the average monthly hash rate is close to 40% and the world’s top two mining companies control a large share of the total mining power network. Such dominance can potentially give rise to systemic threats, even though miners’ substantial investments in specialised infrastructure suggest they may have strong economic incentives to preserve rather than undermine the network’s integrity.

In addition, for PoS networks, such as Ethereum and Altcoins, stake concentration similarly translates into disproportionate governance control. Large liquidity providers, which are usually run by a corporation or invited partners, can shape protocol decisions and censor activity. Centralisation may be common in traditional web/cloud architecture, with firms like Amazon (AWS), Microsoft (Azure), and Google (GCP) hosting large portions of internet infrastructure, but these companies operate under service-level agreements, brands, and regulatory oversight, which do not apply to most crypto projects today.

Quantum computing is a systemic, long-term risk to nearly all crypto assets that rely on classical public-private-key cryptography10. Owning Bitcoin, for instance, means owning a private key, which is a secret code that lets the owner access and spend their coins. The private key is matched to an automatically-generated public key – a Bitcoin address – which is used to receive funds. Any transaction requires the private key to create a digital signature to prove that the recipient of the transfer is the rightful owner. The public key, which is revealed during the transaction, is used by the network to verify the recipient’s signature, before accepting the transaction and adding it to the blockchain. This one-way relationship, from private to public, is what makes the system secure.

If, however, a sufficiently powerful computer becomes available, this security is no longer guaranteed: quantum computing could break the cryptography that protects these keys and derive users’ private keys from the public ones. As of mid-2025, more than a quarter of all mined Bitcoin potentially sit in addresses whose public keys are exposed. In this context, PoS systems, while still prone to vulnerabilities in the codes that back smart contracts, are more adaptable, have more frequent upgrades11 and often show more developer coordination, which would likely facilitate an adaptation to a post-quantum world12. PoW networks like Bitcoin, on the other hand, may be slower to move to quantum-resistant solutions, unless the threat materialises.

Market stress could trigger liquidity crunches if governance or collateral quality fails. Also, widespread use of stablecoins outside of banking, which operates with guardrails, could pose challenges to global monetary sovereignty. Such challenges are unlikely to arise from the quality of the collateral but may instead be linked to structural shifts in who controls monetary instruments, how capital moves, and which currency becomes dominant in everyday economic life. This last point is particularly relevant if trust in local institutions is weak. The main risks are linked to further dollarisation that may be beyond central banks’ control, the risk of capital flights that might destabilise local banking systems and jeopardise official foreign exchange reserves, and regulators and tax authorities having less information on who is conducting transactions.

While the crypto industry has made significant strides since 2022, partly due to the regulations outlined earlier in this paper, anti-money laundering (AML) and Know Your Client (KYC) gaps remain (Travel Rule compliance is not always easy to achieve). Pseudonyms allow transactions to be conducted without full verification of identities; peer-to-peer transfers and non-custodial wallets are not regulated, and decentralised protocols often lack central KYC enforcement, which could allow sanctions evasion and capital flight. To grow and enhance its credibility, the digital asset industry must balance decentralisation with responsible compliance, leveraging technological solutions at a time when regulatory frameworks are becoming more harmonised. There are potential solutions that could close some of these loopholes, including the deployment of what is known in cryptography as a zero-solution proof. This is a protocol in which one party (the prover) can convince another party (the verifier) that some given statement is true, without conveying to the verifier any information beyond the mere fact of that statement's truth.

On-chain analytics, and on-chain identity standards13 are other alternatives. These solutions are particularly interesting as rapid advances in AI shape digital experiences, content creation, and decision-making processes. The immutable and transparent nature of distributed ledger technology (DLT) offers a powerful antidote to the risks of misinformation and synthetic data generated by AI models. By timestamping and cryptographically verifying the origin and integrity of the data, blockchain could potentially help trace the provenance of content and validate whether it was created by a verified person or machine.

Hundreds of crypto projects fail annually due to mismanagement and fraudulent behaviour. Hacking, thefts, and scams also continue to be an issue. While exchanges can go bankrupt or service failures may affect holdings, Bitcoin has a lower risk of a project defaulting. Altcoins and Defi are more exposed given the proliferation of small projects that lack financial resilience, auditing, and transparent governance. Meanwhile, stablecoins face credit and reserve risks: algorithmic stablecoins, which are backed by synthetic rather than physical collateral, are more vulnerable to collapse.

What distinguishes successful innovations is not the absence of risk, but rather society’s ability to understand, manage, and adapt to those risks over time.

Conclusions

The cryptocurrency ecosystem has undergone a profound transformation over the past decade, evolving from a niche experiment into a complex and multifaceted sector at the intersection of finance, technology and geoeconomics. Adoption is broadening across retail and institutional users, supported by maturing infrastructure and regulatory frameworks that are gradually advancing. A clear distinction has emerged between foundational technologies like Bitcoin, programmable blockchains such as Ethereum, and stablecoins. These segments differ markedly in design, utility and risk profile, and these variations are important for investors to bear in mind if they are considering investing in digital assets.

This evolution paves the way for friction. While regulators are trying to impose more oversight, a range of inherent vulnerabilities remains embedded in the design, operation and adoption of cryptocurrencies. New breakthroughs and risks partially explain one of the structural features of crypto markets: their heightened volatility. Persistent scepticism and uncertainty often translate into higher price fluctuations in any asset class. The structure of the digital asset market amplifies this phenomenon. Unlike traditional markets, which operate on fixed schedules and are often segmented by geography, crypto markets are open all the time. Just as private assets tend to exhibit artificially lower volatility due to illiquidity and periodic pricing, public crypto markets are prone to being more volatile due to constant price discovery.

These challenges are neither surprising nor unique to cryptocurrencies. Throughout history, every major technological advancement has brought with it a set of uncertainties, pitfalls and disruptions. What distinguishes successful innovations – such as email, the internet, smartphones and cloud computing – is not the absence of risk, but rather society’s ability to understand, manage and adapt to those risks over time. Time will tell whether blockchain technologies and cryptocurrencies will enjoy equal success, but right now they seem to be following similar trajectories. This is likely to require informed oversight, adaptive regulation and collaborative development.

Investors, developers and policymakers therefore need to take a nuanced approach: one that embraces innovation while remaining acutely aware of evolving risks and structural characteristics.

1. Approximately 144 blocks are added to the Bitcoin blockchain daily, while new Bitcoin supply per year is a function of block rewards. In 2009, which is known as Genesis year because that is when the first block was created, the block reward started at 50 BTC, it has halved in 2012, 2016, 2020 and more recently in 2024. The block reward was 3.125 BTC on July 2025.

2.Most altcoins use different consensus algorithms (Proof of Stake, or PoS) relative to Bitcoin (Proof of Work, or PoW). Ethereum, for instance, transitioned from PoW to PoS in September 2022. The event is known as “The Merge” and effectively ended Ethereum’s reliance on energy-intensive mining.

3.Similar roles are played, for instance, by SOL on Solana or AVAX on Avalanche.

4.Tokens issued by such protocols are generally referred to as “security tokens” and are digital representations of real-world assets (like equity, debt, real estate and commodities), that are issued and traded on blockchain networks with regulatory compliance features.

5.RWA.xyz

6.DeFiLlama, July 2025

7.Circle Internet Group, commonly known as Circle, has listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), by launching their initial public offering (IPO) in June 2025. This marked the first major crypto firm to IPO since Coinbase.

8.Proof-of-Work networks (PoW) differ from Proof-of-Stake (PoS) networks in the consensus mechanism that validates token transactions. PoW relies on computational power as miners compete to add new blocks with energy-intensive work. PoS networks, like Ethereum 2.0, select validators based on the amount of cryptocurrency they “stake” or lock up as collateral.

9.As of September 01, 2025, The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index is updated daily and provides theoretical extreme scenarios to capture minimum/maximum energy consumption.

10.Most blockchains rely on ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm), which could be broken by quantum computers using Shor’s algorithm

11.Upgrades happen by running “intentional forks” on the network: a technical phenomenon used by developers to implement changes to the protocol of a given network. After the fork, a blockchain splits into two separate branches, which share their transaction history up until the point of the split and go in their own direction from there onward.

12.Many newer platforms (e.g. Algorand with Falcon, QRL using XMSS, Hedera with SHA 384) are employing or investigating quantum-resistant cryptography.

13.Blockchain networks need to encourage adoption of interoperable, reusable digital identity standards (i.e. decentralised identifiers and verifiable credentials) and integrate “zero-knowledge proofs” to allow KYC verification without disclosing personal data. In cryptography, a zero-knowledge proof is a protocol in which one party (the prover) can convince another party (the verifier) that some given statement is true, without conveying to the verifier any information beyond the mere fact of that statement's truth. In light of the fact that one should be able to generate a proof of some statement only when in possession of certain secret information connected to the statement, the verifier, even after having become convinced of the statement's truth, should nonetheless remain unable to prove the statement to further third parties.