Summary

Following nearly two decades of negotiations that gained traction only in the past few years, the European Union (EU) and India concluded their discussions on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) on 27 January. This agreement is significant, as it brings together two of the world’s largest economies, with a combined population of around two billion. The European Commission (EC) will submit the agreement to the Council and, after the Council’s adoption, the consent of the European Parliament and ratification by India, the FTA will become operational.

With bilateral trade between the EU and India already being in excess of €186 bn, the FTA allows EU companies to access a high growth market, much-reduced tariffs than before in the automotive, consumer staples, and industrial sectors. Indian exports in sectors such as textiles, jewellery, pharmaceuticals and defence sectors would also benefit.

Importantly, this deal will not immediately increase European exports or earnings but would provide European companies access to a large and growing pool of Indian consumers who are getting richer. It also reduces the volatility of earnings because they are more diversified.

Beyond the financial gains, we think this deal is a way for Europe to hedge its bets (with respect to the US and China), rely on growth centres of the world with a democratic governance model and diversify its exports. In an uncertain world where global policies are becoming more transactional in nature, such agreements improve the quality of Europe’s global exposure. Markets would appreciate this as a source of resilience and diversification of European growth in the long run.

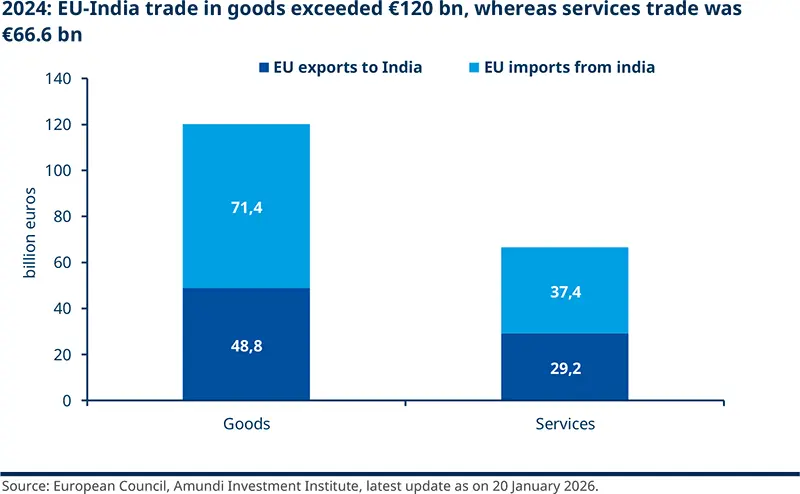

EU-India bilateral trade in goods and services stood at €186.8bn in 2024 underscoring the importance of this trade agreement.

On 27 January 2026, the European Union and India have formally concluded negotiations on a landmark free trade agreement (FTA), marking a major milestone nearly two decades in the making. Legal vetting—or “textual scrubbing”—is now underway, with both sides aiming to complete the process and sign the agreement within five to six months. Once ratified, the deal is expected to enter into force in early 2027.

Already, the India-EU trade is substantial, with the latter being India’s second largest trading partner. Bilateral goods trade between the two stood at €120.2bn and services trade at €66.6bn, for the year 2024. Indian exports to the bloc totaled €108.8bn.

What are the Key Market Access provisions in this FTA for EU?

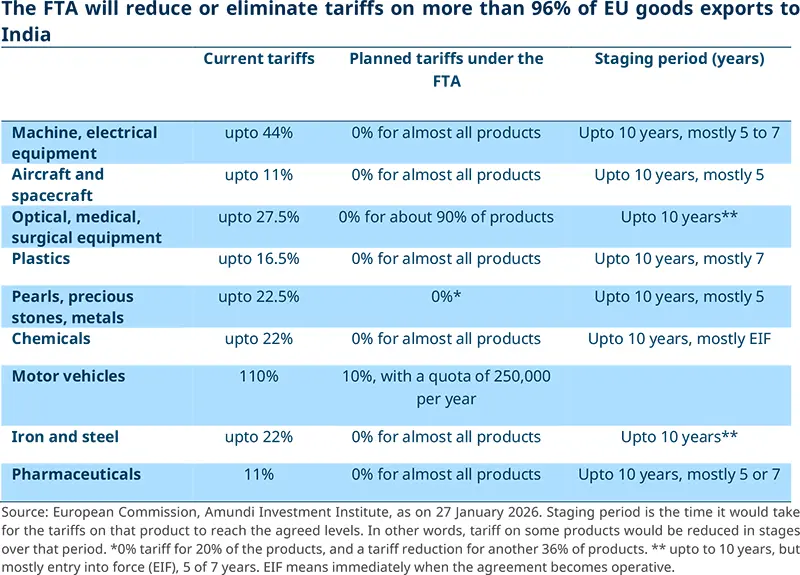

The agreement aims to reduce tariffs EU exports such as machinery, aircrafts, surgical equipments and motor vehicles. Additionally, certain agri-foods have also been included in the agreement.

EU’s automobile manufacturers will gain better access to a market long dominated by domestic and Japanese brands. The EU’s share of India’s car market currently stands at just 4%, suggesting significant potential upside for European exporters. The table below outlines the some of the main tariff reductions that the agreement would bring in for EU businesses:

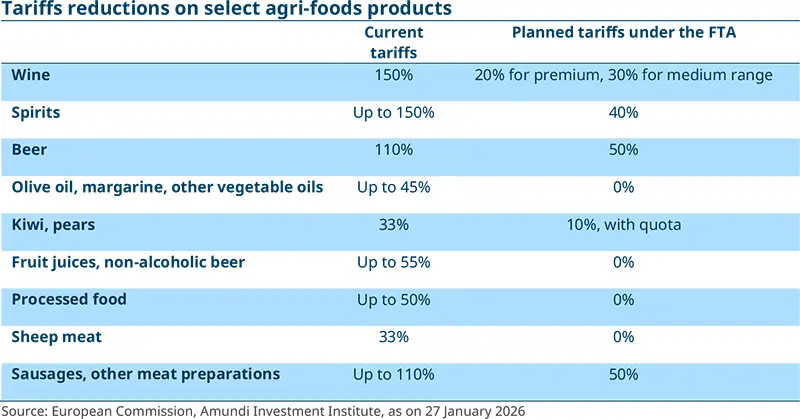

Agricultural sector is a sensitive issue for both the EU and India but the EU received concessions on some agri-foods such as alcoholic beverages, with additional benefits on consumer staples products, outlined below.

Notably, tariffs on imported alcoholic beverages and wine will drop from 150%, providing a substantial opening for European producers, particularly from France, Italy, and Spain.

Benefits for India:

Indian exports of textiles and jewelry should gain duty-free access, aligning with the treatment enjoyed by Bangladesh and Pakistan. The move strengthens India’s competitiveness in Europe’s large consumer market.

The EU should adopt more flexible regulatory standards for Indian pharmaceutical exports, easing market entry for Indian generics and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

The agreement also includes joint defence production initiatives, offering India alternative industrial and employment opportunities as it gradually reduces dependence on Russian defence partnerships—a shift seen as beneficial for both India’s manufacturing base and European defence industries, particularly in France.

Beyond these benefits to the industry, how do you view the FTA in the context of an increasingly fragmented world?

This deal should be seen from the point of Europe partnering with growth centres and middle-income countries with similar governance structures in a world where multi-polarity would remain a norm.

The negotiations between the two sides, initially launched in 2007 and suspended in 2013 after 15 rounds of talks, were revived in 2022 amid global trade realignments, supply chain disruptions, and rising protectionism. The agreement’s timing is strategic: it reinforces supply-chain diversification away from China, hedges against U.S. tariff uncertainty, and underpins Europe’s effort to secure trusted partners in a more fragmented global economy.

The agreement also illustrates the growing importance of “middle powers” in a more fragmented international system, where influence is increasingly exercised through diversified partnerships rather than tight bloc alignments. With great power competition among the US, China and Russia intensifying, states such as India and the EU’s larger members are using trade, technology and security agreements to preserve strategic autonomy and avoid over dependence on any single partner.

In this context, the India–EU FTA functions as a hedging and diversification tool for both sides: Brussels gains a scalable, democratic partner in Asia to underpin economic resilience and clean tech supply chains, while New Delhi reduces exposure to volatile US tariff policy and to China centric manufacturing networks.

Recent analysis of global influence trends suggests that while traditional superpower reach has plateaued, middle and mezzanine powers are expanding their room for manoeuvre by multiplying cross regional agreements and issue specific coalitions. The parallel push by countries like Canada to deepen ties with India in areas such as critical minerals, uranium and LNG—partly to lessen dependence on the US market—fits the same pattern of middle power diversification.

For India, whose oil imports from Russia remain significant at around 1.3 million barrels per day despite declining from peaks near 2 million, this strategy is about balancing long standing relationships with a wider set of economic and political partners.

Do you believe this agreement will allow Europe to diversify its reliance on the US and China

The agreement offers both Europe and India an opportunity to diversify their reliance (in terms of consumer base, supply chain and geopolitical interests) on any one single global superpower.

A challenge for Europe in an environment of controlled disorder is to maintain economic growth, but do so without excessively relying on any one particular region. We believe Europe is not short of global exposure; but it’s short of balanced exposure. Over the past decade, Europe’s external growth has become increasingly concentrated—geographically and politically—most notably toward China and the US. In today’s environment, this concentration carries a cost in terms of volatility, tail risks and valuation uncertainty.

Thus, when viewed through the prism of markets, the EU–India FTA is less about trade volumes and more about how Europe navigates a world of controlled disorder. The agreement does not change Europe’s cyclical outlook, but it changes the geometry of risk facing European assets. And for investors this distinction matters. The EU–India agreement should therefore be seen in that context rather than purely a macroeconomic gamechanger. It does not deliver growth acceleration, doesn’t change Europe’s cycle and is unlikely to rewrite the region’s macro-economic assumptions.

However, it gives a degree of freedom to Europe’s growth model and improves the quality of Europe’s global exposure. In an uncertain world, this quality—resilience, diversification and optionality—is precisely what markets increasingly price. Europe’s opportunity doesn’t lie in growing faster than others, but growing with fewer fragilities. The EU–India agreement is a step in that direction.

How this ‘European resilience’ may affect the region’s investors?

While this deal would not result in any immediate re-rating of EU growth or EU companies, it does provide these businesses stability and access to high a growth market.

For equity investors, the relevance of the FTA lies in optionality and duration, not immediate earnings upgrades. India offers European companies a large but still underpenetrated market, a different demand profile from China and a long investment horizon driven by demographics rather than leverage/debt.

This matters particularly for sectors where Europe already competes on quality, branding and technology, rather than on price alone. Premium industrials, capital goods and autos benefit from the ability to rebalance global exposure without abandoning scale. Luxury and branded consumer goods gain incremental demographic duration, extending growth visibility beyond the current cycle. Defence and aerospace benefit from reinforced cash-flow visibility, anchoring a theme that markets already recognise but continue to underprice in duration terms. The result is not higher growth expectations, but greater confidence in earnings resilience.

For corporate credit and FX investors, the impact is incremental but directionally supportive. For European corporates, broader export diversification reduces sensitivity to single-country shocks and tariff regimes. This improves credit resilience, not spreads. For the euro, the implications are second-order. Over time, deeper trade relationships support transactional use of the currency in Asia, but this is a stabilising force rather than a trend driver.

Overall, the market’s reaction is likely to be gradual and selective, expressed through dispersion rather than broad beta. This is because the agreement does not alter Europe’s medium-term growth ceiling and doesn’t offset structural productivity challenges for Europe and is unlikely to trigger a re-rating of Europe on macro fundamentals alone.

That said, in a fragmented world, markets increasingly reward systems that manage disorder rather than eliminate it. Europe’s strength is not speed or scale, but its ability to embed economic relationships within institutional frameworks. The EU–India agreement reinforces this characteristic. It strengthens Europe’s role as a rule-based trade actor, a partner of choice for middle powers and a diversified node in a multi-polar global economy.

For investors, this translates into lower tail risks, improved risk-adjusted returns and more stable valuation anchors relative to more binary geopolitical exposures.

Which European sectors would you like to focus on as a result of this deal, and even more generally?

European companies in the automotive, staples and defence sectors would benefit in the long term.

The agreement is a positive move for European trade developments in the long term, with the agreement diversifying partners and facilitating better access for European companies to the structurally growing Indian market (which has population of c. 1.5 billion). But we think the near-term incremental impact on earnings is likely to be muted and therefore we do not expect any material re-rating of valuation multiples on the back of this news. We also note that the deal could be particularly helpful for non-listed European SMEs (small and medium enterprises), opening new growth opportunities as they scale businesses.

In particular:

Companies operating in the automotive, consumer staples, and industrial sectors are best positioned to benefit from better access to the Indian market. However, some of the tariff reductions are only set to be phased out in differing stages over the next decade, so this is likely to play out more as a medium to longer-term tailwind.

For auto companies, tariffs on EU motor vehicles are set to fall from 110% to 10%, although a quota set at 250,000 vehicles per year will cap the potential upside from the relief. Nevertheless, the tariff reductions are to be welcomed given the structural pressures facing European original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) from the increased competition in home markets and the move to electric vehicle (EV) transition. India is currently a small market for the large European OEMs (less than 1% of sales), but notably a large part of Indian demand appears to be currently focused on lower price point vehicles (which is not an area where European OEMs are currently very competitive).

European chemical companies have only a small exposure to India, and a lot of the production is local-for-local. So, there is likely to be minimal direct impact (e.g. some industrial gas companies). In general, India is trying to become more self-sufficient in chemicals, so the longer term consideration is whether India can further build out its industry, which leads to further commoditisation of existing chemical production. In the consumer staples sector, food and alcohol companies are set to benefit from tariff decreases.

Defence initiatives between Europe and India stand to benefit from a localised value chain, especially in aircrafts. For instance,

Some European and Indian companies are establishing final assembly lines (FAL) in India to produce helicopters and military transport aircraft.

A French aircraft and aeronautics company has already begun establishing maintenance, repair and operations (MRO) facilities in India. Any additional aircraft order would involve the introduction of local production facilities. Another aviation company is establishing production facilities for a specific aircraft engine in India.

Longer-term, we could see India’s involvement in development of Europe’s sixth-generation combat aircrafts.

Overall the new agreement and better trade relationships are a helpful development for Europe, but not something we see materially changing fundamentals of listed companies over near-term.