Summary

Introduction

Blended finance structures are key to deploying catalytic capital coming from public, philanthropic, and private sector sources. The combination of the three allow for investors to pool essential capital meeting sustainable or development financing needs (e.g., SDGs, NDCs) in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs).

Blended finance is a structuring approach, and while seen as an effective means to deliver on both sustainable impact and risk-adjusted return objectives, questions on scalability and the complex nature of these structures remain.

Within the ecosystem of development finance, scaling up the use of these structures to mobilize larger flows of capital into EMDE starts with understanding what kind of blended finance structures exists, and what investors should be considering when entering these types of investments. Investors need to get familiar with the risks and opportunities of this structuring approach and the techniques available in the market, to understand how to mitigate perceived risks.

This paper provides clarity for investors on key characteristics of credit enhancements in blended finance structures. We address perceived investment risks in EMDE, and demonstrate which credit enhancement characteristics at the portfolio and transaction level can mitigate those perceived risks.

If blending techniques can be replicated by private and public investors and added to their investment toolbox, blended finance structures would have the conditions for market development and future scale, thereby having the potential to close the development financing gap. Our findings complement materials on standardization of blended finance structures or archetypes that exist in the blended finance space. We explore how credit enhancements at the portfolio level can be supercharged with the use of a guarantee or risk transfer mechanism within the structure, and at how different type of credit enhancements can help transactions (such as bonds or loans) become more attractive for investors.

By bringing awareness and assessing the strengths and limitations of different credit enhancement characteristics available in the market, our aim is to enable investors to make informed decisions when assessing blended finance opportunities in alignment with their investment preferences. Under these circumstances, investors contribute more broadly to the standardization of different credit enhancement approaches.

Key findings

Despite its potential to mobilize catalytic capital from public and private sources, blended finance currently represents a small fraction of total development finance (2% of total MDB investment). Scaling blended finance requires structural standardization, replication, and greater private sector participation.

Country risk, regulatory constraints, currency volatility, and concerns about default rates have consistently acted as a behavioural and financial barrier to investment in EMDE. Some of these risks can often be mitigated, but others are grossly misperceived. Take for example, corporate default rates, which are conventionally seen as being significantly higher in EMDEs, when in fact default rates in EMDEs have been lower than global corporate default rates, across both investment-grade issuers and speculative-grade issuers1.

This is reflected in the distribution of sovereign credit ratings: in 2023, 63% of sovereign credit ratings in developed countries were in the A- to AAA range, compared to 11% in EMDEs2.

Breaking through the perception trap is key for investors, so that they can focus on mitigating actual risks within their EMDE investment allocation and participate in scalable blended finance solutions.

Tools such as first-loss guarantees, political risk insurance, and partial credit guarantees help mitigate the above-mentioned risks, making blended finance structures more attractive and accessible to private investors. Mirroring the uptick in MDBs/DFIs blended finance activity, their use of guarantees has followed suit. For example, the IFC’s use of guarantees for long-term financing rose by more than 160% from FY 2023 to FY 2024, while loan and equity disbursements remained stable3. Bolstering this trend is the launch of the World Bank Group’s unified guarantee platform4, which aims to triple annual guarantees to $20 billion by 2030.

Private creditors view guarantees and insurance as the most effective in blended finance structures, followed by blended finance funds and facilities that address de-risking through mezzanine finance5.

These funds combine public and private capital, use first-loss capital or guarantees, and can incorporate portfolio-level currency hedging to stabilize returns and protect investors from currency depreciation. The introduction of catalytic first-loss capital (CFLC) within these funds, via equity, grants, guarantees, or sub-ordinated debt—can further de-risk positions taken by private sector investors.

In 2024, guarantees were the top instrument used in blended finance transactions, accounting for 46% of concessional instruments used.

Credit enhancements enable longer maturities, better pricing, and local currency financing, thereby catalysing more private capital into sustainable development projects.

Though, challenges remain to ensure standardisation and smoother processes for investors.

1. Private investor capital and awareness is key in scaling up blended finance

A. Blended finance structures and their potential in meeting the SDGs

Supporting sustainable development, mitigating climate change impacts, or improving the livelihoods of the global population have been the centrepiece of public and private debate, and yet the financing gap continues to widen. In EMDE, the impacts are felt the strongest, and yet there is a disconnect between the funding needs and what has been delivered. The latest UN Sustainable Development Goals Report confirms the lack of progress made – with only 5 years left to meet the 2030 SDG targets, only 20% are on track to be met6. An estimated $4 trillion is necessary to meet the SDGs in EMDE7 which is 19 times the amount mobilized through official development aid (ODA)8.

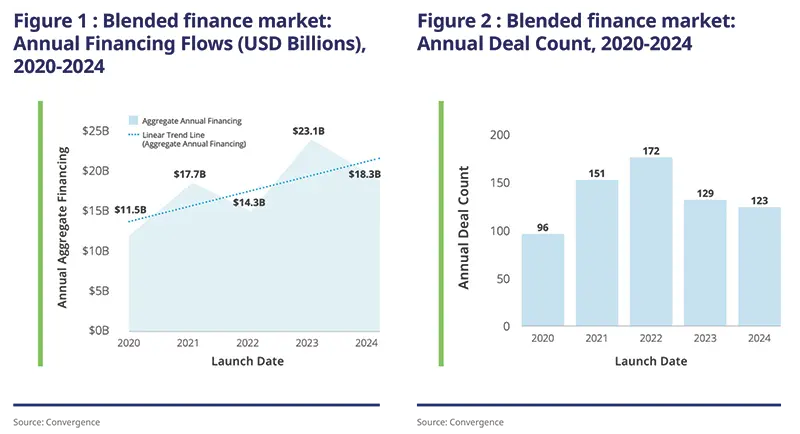

If we look to blended finance structures as one of the potential solutions to the challenge we face, the current mobilization of these investments is still modest. In 2024, the number of transactions remained stable with 123 deals (vs. 129 in 2023) and the total volume of blended finance flows reached $18.3 billion (vs. $23.1 billion in 2023), which was well above 2020 levels ($11.5 billion)9. According to Convergence’s report, the sustained level of activity suggests that the blended finance market has been resilient during this period of macroeconomic volatility and part of a broader upward trend if compared to previous years.

Additionally, median deal size has been increasing from $38 million (2020-2023) to $65 million (2024) – reflecting growing ambition and scale in deployment. Overall, the blended finance market has shown promise, with 1350 transactions totalling $249.2 billion in volume10. In terms of impact, blended finance structures have enabled MDBs and DFIs to mobilize $0.50 of private capital for every dollar committed from their balance sheets between 2019 and 2021. Nevertheless, blended finance structures still account for less than 2% of total MDB investment11. The positive signals of the blended finance market’s growth are promising, but deepening the market will require more than just large and unique deals. Structural standardization and replication of blended finance structures will be key to respond to urgent SDG financing needs.

B. Mobilizing private sector capital to scale and deepen blended finance structures in EMDE

By leveraging private sector participation in blended finance structures, we multiply the sources of capital to ensure a pathway toward closing the SDG financing gap. Blended finance funds are a well-suited solution not only for private investors seeking to allocate impact-oriented capital in EMDE, but also for mainstream investors solely focused on financial terms, as it can fulfil a dual objective: investing in financial products with more favourable terms not only to the end obligor (which could include lower interest rates compared to commercial loans, extended repayment periods, or grace periods during which principal or interest payments are deferred) but to the investors offering compelling risk-adjusted returns versus vanilla products. Such terms can be tailored to the specific financial circumstances of the borrower, making debt service more manageable. Furthermore, blended finance solutions integrate concessional (or first-loss) capital which plays a critical role in de-risking sustainable development projects in EMDE by absorbing part of the financial risk.

This risk-sharing mechanism incentivizes private sector investment in sectors or projects in EMDE that might otherwise be considered too risky to carry out through direct investment12. Appealing blended finance structures allow private sector investors, both impact investors and mainstream investors, to support a larger pool of projects that they could not finance by themselves alone.

Since 2022, private investors have invested approximately $20 billion in blended finance deals, which account for 32% of total commitments in blended finance transactions in the past 3 years. We expect private sector contribution to only increase as last year’s G20 roadmap13 signalled the need for MDBs to maximize their development impact by enhancing private capital enablement alongside their efforts to leverage more financing from their own balance sheets. However, harnessing private capital mobilization requires all stakeholders to be clear-eyed on the challenges that hold back private sector investment from entering EMDE14.

C. Risks currently deterring private sector investors from allocating more capital to EMDEs

Private investors are primarily focused on achieving risk-adjusted returns, and their perception of risk plays a crucial role in their decisions to invest in emerging markets (EM) in addition to other key factors such as liquidity and market depth. Historically, there has been a strong case for investing in EMs, supported by solid long-term performance data15. However, looking at how institutional investors16 allocate their capital, EM still represents a small portion of their overall investments, often falling short of “rational allocation strategy” levels17. This indicates a significant gap in capital allocation that needs to be addressed.

It is key to acknowledge that the flow of funds into emerging markets (EM) has experienced significant volatility in the past decade. During the period from 2008 to 2021, low interest rates in developed markets encouraged a widespread “search for yield” in EMs18. The landscape shifted in 2022, with an unprecedented $90 billion exiting EMs, and outflows extending into 2023, and the first months of 202419. The surge in sovereign defaults post-pandemic, coupled with the geopolitical ramifications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, exacerbated existing vulnerabilities within EM20. 2025 marked a stark contrast as EMs witnessed a net $35.4 billion inflow of international capital in January alone.

This surge takes place in the context of a multipolar world, where the origins and destinations of capital flows become more varied, with global centres emerging outside of development markets and playing a larger role in global investment. According to Amundi’s experts, although rising geopolitical tensions21 are significantly impacting EM, this shift may benefit some of them by enhancing their bargaining power and political influence22. This evolving landscape suggests a potential shift in capital allocation in EMs, also driven by improved governance and more transparency23, and highlights the importance of perceived levels of risks as a driver to attract private capital in developing economies.

Looking at which barriers impact investor decisions, a recent survey by PwC and the World Bank24 identified “country risk” as a major concern deterring EM investments. Key factors contributing to this concern include political instability, potential high inflation, rising interest rates that increase borrowing costs, and limited foreign exchange availability, which complexify the repatriation of earnings. Historical evidence indicates that country risk has been the most significant driver of returns in EMDEs25. Traditionally, investors have sought to mitigate country risk through cross-country diversification, limiting their exposure to EMDEs as a group. However, global shocks tend to increase the correlation of country risk across different countries, diminishing the effectiveness of diversification strategies. This trend may result in reduced allocations to EMDEs overall or greater selectivity regarding which countries to invest in.

The second investment barrier identified by the survey is regulation, as global regulators respond to the perceived risks in EMs by imposing stricter requirements that limit investment for financiers. For instance, the Basel III agreement introduces conservative capital reserve requirements for financing infrastructure projects in EM, which lead to higher interest rates charged by commercial banks, making it more challenging for these markets to attract necessary project financing26. Similarly, Solvency II, a key regulation for European insurers, encourages investment in safer, more liquid assets, thereby rendering riskier EM investments less appealing27. Additionally, the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and taxonomy add another layer of complexity by imposing reporting criteria that may not be well-suited to data availability in EMDEs, potentially limiting investment flows and undermining the EU’s sustainability goals in these regions28.

Another risk for investors considering investments in EMDE is default risk. Default rates are a guiding metric for investors as they indicate the frequency with which borrowers fail to meet their financial obligations. A recent study via the Global Emerging Markets Risk Database (GEMs)29 challenges the notion that EMDEs are high risk environments. While default risk is a major concern for global investors, the study analysed default rates over six major periods of economic stress in the past 30 years and found that default rates for emerging market firms in the GEMs portfolio did not rise as much as default rates for similarly rated corporates in advanced economies30. Another compelling insight from the study is that there is a negative correlation between a country’s sovereign risk rating and the default performance of its companies31. This point challenges the idea that investments in companies or private-sector projects in low-income countries are excessively risky. Instead, it suggests that there are viable pathways for EM investments, even in the face of perceived default or credit risk and provides an encouraging nod to investors wanting to enter investments in EMDE. However, we must note that the GEMs data reflects the unique experience of DFIs and MDBs, who have a deep understanding of their local markets and have the resources to mitigate project and borrower risk in their transactions – thus contributing to lower default rates.

In summary, addressing the investment gap in EMDE and scaling blended finance solutions in these markets requires investors to better understand the associated risks, but also look to solutions such as de-risking mechanisms and ones that improve credit profiles. Credit enhancement mechanisms provided by public sector entities, such as MDBs and DFIs, are essential in this context.

2. Credit enhancements and blending techniques in structured debt solutions

As seen above, the challenges posed by country risk, regulatory constraints, and global volatility create a complex landscape for capital allocation in EM. Addressing these barriers is crucial for unlocking the potential of EM investments, particularly in the context of climate finance, which requires long-term debt at lower rates32.

To bridge this gap, credit enhancement mechanisms play a vital role in blended finance debt solutions. Credit-enhanced debt has been a fundamental aspect of lending since its inception; for example, mortgages are often secured by the borrower’s property33, while other assets may serve as collateral for loans or bonds34 35. By providing credit enhancements, borrowers can access financing at more favourable rates or even qualify for loans that might otherwise be out of reach36. Given the credit risks associated with investments in emerging markets, these enhancements can significantly facilitate access to capital.

Various methods of credit enhancement have emerged, both at the deal and fund levels, proving to be effective in leveraging private capital. An International Institute of Finance (IIF) survey indicates that private creditors view guarantees and insurance as the most effective blended finance structures, followed by blended finance funds and facilities that address de-risking through mezzanine finance37. This section discusses how the latter can be supercharged with the use of a guarantee or risk transfer mechanism within the structure (Section II.A), and at how different type of credit enhancements can help transactions (such as bonds or loans) become more attractive for investors (Section II.B).

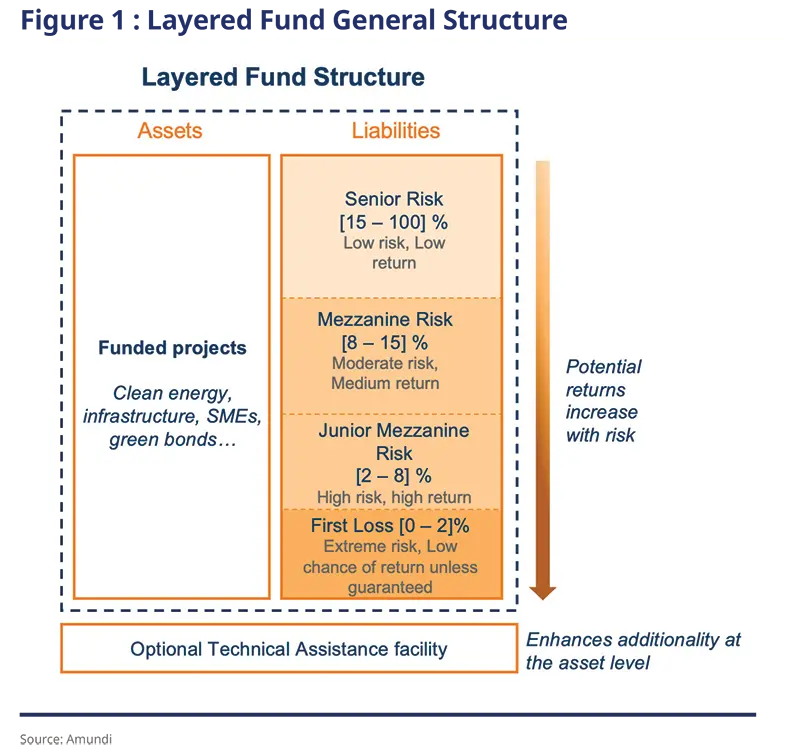

A. Credit enhancements at the portfolio level: layered funds as a promising avenue for enhancing investment in EM

Layered funds, which inherently share risk across investors, present a promising avenue for enhancing investment in EM. Amundi has significant experience with such funds, including the Amundi Planet Emerging Green One fund (AP EGO) and Amundi Planet Sustainable Emerging Economy Development Debt (SEED) funds which cumulatively stand at USD 1.8bn. Both funds developed in collaboration with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) exemplify how layered structures can effectively mobilize capital while managing risk to meet sustainable finance outcomes in EMDE.

Layered funds can provide investors with exposure to debt in EMDEs focused on sustainable investments, while also offering access to diversified portfolios that carry lower risk compared to direct investments in the sub-assets. The introduction of catalytic first-loss capital (CFLC)38 within these funds, via equity, grants, guarantees, or sub-ordinated debt—can further de-risk positions taken by private sector investors. This structure allows for the implementation of investment programs that align with the objectives of sponsoring institutions and the risk-return profiles of prospective investors. Funds supported by Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) thus often benefit from a “halo effect,” enhancing their attractiveness to private investors.

A well-structured fund can appeal to sponsors and managers, as well as investors, for several reasons:

Funds can make active trading decisions, unlike the largely passive nature of securitizations.

Funds typically do not require a credit rating, while most tranches of securitizations do39.

Fund tranches may not need to be marked-to-market, allowing for stable valuations even during periods of high asset price volatility.

Closed-end funds prevent capital withdrawal, ensuring stability.

De-risking strategies can be applied to various tranches which can offer different risk/return pairs to cater to different kinds of investors with different risk/return appetites.

Funds can easily incorporate multiple guarantors or combine guarantees with collateralization.

On the liability side, a fund can attract a mix of public and private investors providing equity and debt funding. Public sector or philanthropic equity investments, made upfront with a legal commitment to remain in the fund, are crucial for mobilizing private capital. These investments earn returns based on the performance of the fund’s assets. Private sector investors can contribute to the fund’s debt tranches (including mezzanine debt), providing additional resources to support climate projects and scale up private sector funding. Ideally, the fund will adopt a closed-end structure, requiring private investors to commit their capital for a fixed period, which enables the fund to confidently lend to long-term sustainability-related projects while minimizing asset-liability mismatches.

On the asset side, the fund structure offers flexibility in the types of assets it can hold to support sustainable investments. A fund could lend directly to climate/social projects or collaborate with local financial institutions. Additionally, it can purchase GSS40 bonds issued by financial institutions or corporations as another means of supporting climate initiatives.

Case Study: Amundi Planet Emerging Green One (EGO) Fund and the IFC-managed Green Bond Technical Assistance Program (GB-TAP) The concept for the Amundi Planet Emerging Green One (AP EGO) fund was co-developed between IFC and Amundi. The AP EGO fund buys green bonds issued by EMDE-based financial institutions (FIs), targeting specifically systemic banks with a Medium-Term Note program in place. The fund can invest in debt instruments listed on a regulated market and long-term credit ratings by a credit rating agency (CRA), or equivalent credit quality as determined by the Portfolio Manager. The AP EGO fund raised US$1.42bn by the time of closing, when it was the world’s largest green bond fund. The AP EGO fund is registered and regulated in Luxembourg, with its shares distributed across senior, mezzanine, and junior tranches making up 90, 3.75, and 6.25 percents of the liabilities, respectively at closing. The AP EGO fund is 12-year closed-ended with a 7-year investment period (2018-2025) followed by a 5-year runoff period (2025-2030). The fund’s shares were not rated by a CRA, but simulations showed that with a 99% Value-at-Risk (VaR) of 12.5%, just slightly above the senior tranche’s 10% credit enhancement point, and a conditional VaR (cVaR) of 16.7%, possibility of losses impacting the senior tranche was rare and limited in severity. Plus, the portfolio’s expected loss is ~3.47%, compared to the cumulative default probability over 12 years of around 4% for BBB rated bonds. Hence, the credit quality of the senior tranche would have been equivalent to a BBB rating, which helped attract investors’ investment grade fixed asset class allocation. At the time of the fund’s closing, green bonds issued by EMDE-based FIs available for purchase were scarce, and the bulk of the fund’s assets were initially invested in EMDE conventional bonds from financial institutions. Those conventional bonds were sold off over time and replaced by green bonds in the fund’s portfolio – in 2025 the fund met its 100% green bond target. Investors in the junior and the mezzanine tranches include the IFC (which provided US$256m playing the role of fund’s sponsor and anchor investor), the EIB, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and Proparco, as well as private investors; investors in the senior tranche were seven European pension funds, and three insurance companies. The AP EGO fund is subject to a comprehensive environmental, social, and governance (ESG) policy, developed around three pillars: (i) issuer exclusion based on ESG scores; (ii) the assessment of green bond frameworks based on ICMA Green Bond Principles, focusing on transparency and disclosure; and (iii) ensuring high performance standards of the green bonds acquired. The fund’s ESG policy and thorough impact reporting framework were instrumental in attracting private-sector investors in the fund. To bolster the fund’s ability to source bonds from EMDE FIs, the fundraising was accompanied by an IFC-managed Technical Assistance (TA) program, the Green Bond Technical Assistance Program (GB-TAP), that improved the capacity of EMDE-based FIs to issue green bonds. This program was instrumental in notably increasing the overall supply of green bonds that the EGO fund could purchase. The EGO fund and this TA initiative complemented each other in terms of the growth of the green bond market achieved and the improved ability of the AP EGO fund to source bonds41. |

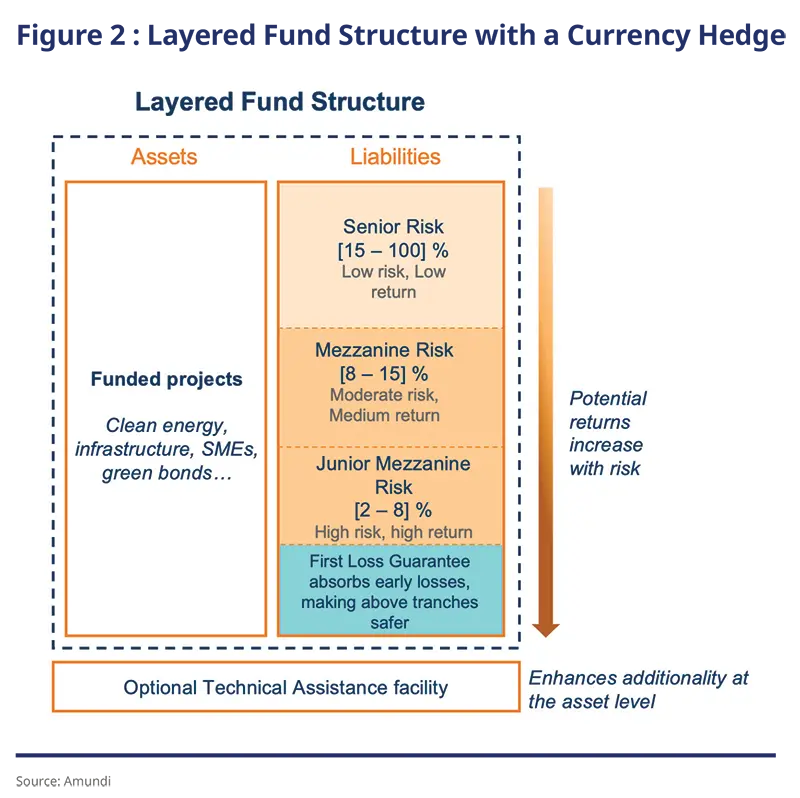

First loss guarantees, essential components of blended structures

Among the guarantees that can be activated at the portfolio level, first-loss guarantees stand out as a key risk mitigation tool for vehicles targeting emerging and developing markets.

First-loss guarantee. A type of guarantee in which the guarantee provider agrees to bear losses incurred up to an agreed percentage in the event of default by the borrower. The purpose of a first-loss guarantee is to reduce risk and attract lenders and investors who may be hesitant to participate in a deal because of concerns about the level of risk involved. By offering to cover the first losses, the guarantee provider reduces the risk and increases the confidence of potential lenders and investors42. |

In 2024, guarantees accounted for 46% of the concessional instruments used in blended finance vehicles43. The effective use of first-loss capital is essential for layered funds, to allow for a tailored mix of capital that can address specific investment challenges44. In 2024, Convergence recorded $1 billion in concessional guarantees, representing a 42% increase from 2023. The growing use of guarantees has also influenced the leverage and mobilization ratios45, with implications on future trends for blended finance. When excluding concessional guarantees from Convergence’s analysis across all years, the leverage ratio increases to 4.37, while the private sector mobilization ratio rises to 2.5.

A blended finance fund can be structured such that the guarantee can be funded or not, which makes it a powerful tool to enhance capital mobilization using different pools of risk capital providers (insurance, sovereign bodies, etc.). In particular, the public sector can provide a collateralized guarantee to de-risk investments benefiting the private sector, without taking an investment position in the fund itself. In this scenario, all funding for the fund would come from private investors, ensuring that the catalytic capital is utilized effectively. As emphasized in earlier parts of this paper, the strategic deployment of catalytic capital is vital; it must be used judiciously to avoid market distortion while maximizing additionality46.

Another variant involves providing the first loss guarantee not on the fund’s liabilities but on the asset side. This structure can be particularly advantageous for insurers, as investments in the senior tranche of a junior/senior tranche layered fund would be classified as a securitization vehicle under Solvency II. This classification could attract more favourable capital allocation treatment, thereby enhancing the overall attractiveness of the investment.

The success of first loss guarantees hinges on finding the right balance in structuring these funds. As noted in the literature, it is essential to determine the optimal amount of guarantee needed to sufficiently de-risk the portfolio and ensure the entire structure functions effectively.

This approach aligns with the broader goal of blended finance, which seeks to create a mix of capital that mobilizes investment in high-risk sectors while delivering meaningful social and economic returns.

This instrument can be applied to the non-junior tranches of layered funds, potentially serving as a tipping factor in securing favourable credit ratings. However, this approach remains novel due to the lack of standardization in the underlying investments. For credit enhancements to alleviate investment risks effectively, they must be perceived as credible and independent of the borrower’s influence. Credit enhancement must be simple, demandable, follow standardized and transparent performance and reporting metrics aligned with market standards, and structured as first-demand guarantees to allow counterparty risk substitutions in practice. Additionally, any claims process should allow for swift resolution, as complex conditions associated with payouts are generally viewed unfavourably by both investors and credit rating agencies. The treatment of partially guaranteed, insured, or collateralized debt in the event of default is another critical factor influencing market acceptance and pricing47. Lastly, the effectiveness of such guarantees depends on the coverage scope, conditions for activation and settlement terms: smooth processes need to be put in place, to avoid additional friction costs or delays that would result in an additional premium required by investors.

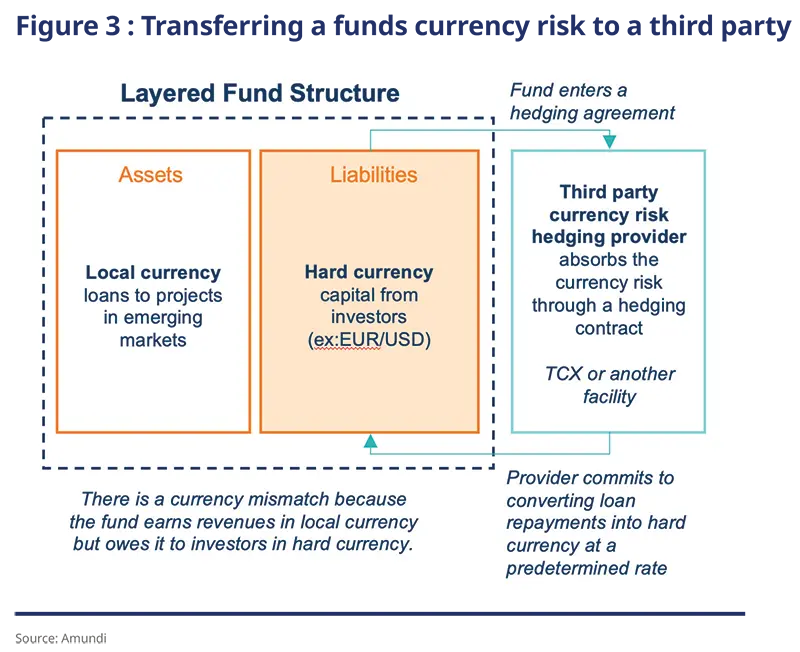

Currency risk mitigation as an indirect credit enhancer

While credit enhancement tools such as first-loss guarantees and subordinated tranches are widely used in blended finance structures to improve the credit profile of emerging market (EM) portfolios, they often fail to address a parallel risk that can equally undermine portfolio performance: currency risk. For foreign investors deploying capital into EM assets, currency depreciation can erode returns or, in severe cases, trigger credit events — particularly when borrowers’ revenues are denominated in local currency while obligations to investors are in hard currency. Beyond Mark-to-Market, foreign investors also face risks related to convertibility and currency controls, especially in LDCs.

Facilities like The Currency Exchange Fund (TCX)48 have emerged as market-driven solutions to this challenge. Established by a consortium of development finance institutions (DFIs), impact investors, and multilateral banks, TCX provides long-term, local currency hedging instruments in markets where commercial hedging is unavailable. Its model allows investors to transfer local currency risk off their balance sheet, stabilizing expected returns and protecting against sudden currency devaluations.

While TCX is often engaged on a transaction-by-transaction basis, it can also be structured to hedge entire portfolios exposed to correlated currency risks. In this approach, the fund or vehicle identifies a set of assets — such as loans to financial institutions or infrastructure projects — whose revenues are denominated in local currencies across one or several countries. TCX then provides cross-currency swaps or non-deliverable forwards (NDFs) covering the expected cash flows of the portfolio over a defined period. The hedge operates by transforming the portfolio’s local currency exposures into hard currency obligations, effectively shielding the investor from devaluation risks that could impact multiple assets simultaneously. Importantly, TCX prices the hedge based on its proprietary models of long-term currency risk — which aims to reflect the true economic cost of carrying EM currency exposures rather than speculative market pricing.

By aggregating exposures at the portfolio level, investors may also achieve better efficiency and risk pooling than hedging asset by asset. This is particularly valuable in sectors like microfinance, renewable energy, or SME lending, where individual projects may be too small to justify standalone hedging but collectively represent material currency risk. In some blended finance structures, concessional capital can also be layered in to subsidize the cost of such portfolio-level hedging, further improving feasibility.

Though currency hedging is not a credit guarantee, its effect on the portfolio’s risks can be very significant. By stabilizing cash flows and shielding projects from exogenous FX shocks, these instruments play a role analogous to credit enhancements — especially when embedded within blended finance vehicles designed to crowd in private capital49.

B. Credit enhancement at transaction or project level

As the market for blended finance transactions continues to evolve, it is essential to acknowledge the various credit enhancement mechanisms can make these programs more appealing to private investors. While Amundi does not structure bonds, it actively invests in them and could find itself participating in blended finance debt transactions, typically issued by Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs).

Recent data from Convergence50 indicates that commercial capital from private sector investors outpaced DFIs and MDBs in capital deployment over the past two years. Notably, the share of commitments made by DFIs and MDBs declined from 2023 to 2024 by 13%, while the share from the private sector decreased only slightly by 2%. The median deal size for blended finance funds has steadily increased from $48 million in 2022 to $100 million in 2023 and $135 million in 2024. This shift signals that funds are emerging as the most scalable and replicable blended finance vehicle, drawing increased participation from the private sector, particularly institutional investors, who require investment assets that meet their fiduciary and regulatory obligations. Notably, after DFIs (23% of commitments), institutional investors held the second largest share of fund commitments (20%) over the past three years.

In addition to credit enhancements at the portfolio level, two key mechanisms that can enhance blended finance transactions at the transaction or project level are: Political Risk Insurance (PRI) and Partial Credit Guarantees (PCGs).

Political Risk Insurance (PRI)

Political Risk Insurance (PRI) serves as a critical tool for mitigating risks associated with sovereign investments, particularly in emerging markets. By providing guarantees against country risk—specifically the portion related to political stability—PRI enables investors to engage in climate-related projects with greater confidence. Recent sovereign bond issued in the context of debt-for-nature swaps highlight the growing relevance of PRI, with notable examples from countries such as Belize, Gabon, Ecuador, and El Salvador, all of which contracted PRIs with the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). These transactions illustrate how PRI can effectively safeguard investors against potential political disruptions.

PRI offers a non-commercial risk guarantee against several key risks, including expropriation, transfer and inconvertibility, war and civil disturbance, and breach of public sector obligations51. This coverage is essential in politically risky investment environments, which are often characterized by arbitrary policies that fail to protect property rights or ensure stable tax rates. Such uncertainty can deter foreign investment, as inadequate protection of property rights and insufficient contract enforcement raise transaction costs for investors. Moreover, the absence of formal and informal institutions necessary to uphold the rule of law can significantly increase risk premiums, further complicating investment decisions52.

The US DFC has emerged as a major provider of PRI, with a portfolio valued at over $7.7 billion. A 2023 McKinsey report53 analysed 14 cases, representing 30% of DFC’s total mobilized capital from active contracts across 10 countries and various sectors, to estimate that the DFC directly mobilized approximately $2 billion in private sector capital, with five contracts accounting for $1.7 billion. Notably, 80% of the DFC contracts reviewed had identifiable second-order private capital mobilized, demonstrating the effectiveness of PRI in facilitating investment. The sectors of nature conservation, resource extraction, and energy emerged as the largest in terms of maximum contingent liability and average maximum coverage size, underscoring the utility of PRIs for leveraging climate-aligned financing.

The mechanics of PRI involve transferring foreign investors’ capital exposure to insurance providers that are less risk-averse and more capable of bearing the associated risks. By curbing country risk premiums, PRI improves the valuation of investments in emerging markets and enhances the internal rate of return of development projects. For instance, a study conducted by S&P Global54 examined a single representative project across three differently rated country contexts—Ghana, Indonesia, and Brazil—and found that PRI coverage typically improved country risk premiums, credit ratings, and increased the internal rate of return and net present value of projects. This indicates that PRI does more than merely cover insured losses; it also confers higher asset valuations and enables investment financing on more favourable terms.

Partial Credit Guarantees (PCGs)

Partial Credit Guarantees (PCGs) offer flexible, transaction-specific protection designed to absorb credit losses on part of the exposure, rather than insuring the entire investment.

While often seen as “vanilla”, PCGs have become increasingly sophisticated, adapting to investor needs by targeting specific risk periods (construction, ramp-up), market segments (local currency bonds), or even refinancing risks55. Their relevance grows in markets where country risks are no longer the primary barrier, but weak credit profiles still deter private capital. Importantly, PCGs can be layered alongside PRIs, allowing investors to address both political and credit risks within a single transaction — a combination that has proven catalytic in sectors like infrastructure, renewable energy, and financial inclusion.

Structurally, a PCG is typically issued by a DFI, MDB, or specialized guarantee facility. It promises to cover a predefined portion of scheduled debt service — often principal, sometimes interest — if the borrower defaults.

Coverage can be:

Pro-rata (Pari passu) with lenders, reducing loss given default,

Mezzanine-style, absorbing first losses, or

Time-bound, covering only high-risk phases like construction.

This flexibility allows PCGs to optimize capital efficiency — covering just enough risk to unlock investment without fully crowding out private participation.

Case Study: combining PCGs and PRI to further mitigate risks Partial Credit Guarantees (PCGs) can be combined with Political Risk Insurance (PRI) to further mitigate risks. For example, in 2022, the EBRD’s Credit Enhancement Facility (CEF) guarantees were paired with MIGA’s PRI to support Scatec, a renewable energy provider in Egypt, in issuing a green bond56. Furthermore, PCGs can also be combined with instruments like Policy-Based Guarantees (PBGs) to help countries secure financing on better terms. A recent example is the €372.9 million MIGA guarantee covering the second-loss layer, which complements the IBRD’s €260 million PBG providing first-loss coverage57. Moreover, PCGs are not just risk mitigants; they are levers for financial additionality. By reducing perceived credit risk, they mobilize private capital into markets and sectors it would otherwise avoid; stretch maturities and improve pricing for borrowers, as well as enable local currency financing, a key demand in many EM contexts. For instance, InfraCredit Nigeria’s local currency bond guarantees have allowed pension funds to invest in infrastructure for the first time58 — proving PCGs’ role in unlocking new investor bases. Similarly, GuarantCo’s guarantees are increasingly used to cover refinancing risk for green bonds, helping institutional investors manage long-term exposures59. Recent studies from the UN-led Blended Finance Taskforce60 notably show that guarantees such as PCGs show the highest mobilization ratios compared to other use of public capital, on average mobilizing $1.5 of private capital for every dollar of MDB capital and outperforming the average mobilization ratio of loans and equities by 6 times. The report, “Better Guarantees, better Finance”61 argues that with structures carefully tailored to investor risk appetites, larger and more effective credit guarantee facilities have the potential to even mobilize 6-25 times more financing than loans. |

Conclusion

Blended finance structures hold significant promise as a strategic approach to mobilize the vast amounts of capital needed to address sustainable development challenges in EMDE. However, realizing this potential requires overcoming persistent barriers related to perceived risks, regulatory constraints, and market complexity. This paper has highlighted the critical role of credit enhancement mechanisms—such as first-loss guarantees, political risk insurance, and partial credit guarantees—in de-risking investments and improving credit profiles, thereby making blended finance opportunities more attractive to private investors.

These tools are continually developed to tackle the risks and barriers that make some projects seem too risky or not bankable for investors. Collaboration among different stakeholders continues to be an effective lever to scale sustainable or blended finance, as seen in the increasing number of innovations and the larger amounts involved; for example, in 2024, the largest debt-for-nature swap stood at USD 1.6 billion, executed by Ecuador, which is significantly higher than in previous years62.

Layered fund structures, combined with innovative risk mitigation tools like portfolio-level currency hedging, offer a scalable and flexible framework to channel private capital into high-impact projects while managing risk effectively. Public and philanthropic sector catalytic capital remains indispensable in these structures, providing the necessary cushion to absorb initial losses and build investor confidence. Though, challenges remain to ensure standardisation and smoother processes for investors, based on simple tools that allow counterparty risk substitutions in practice.

While these collaborative efforts are making a difference, there is still a need for smoother processes and better knowledge sharing, aiming to reduce the cost and complexity of implementing these instruments. Initiatives like the World Bank’s new guarantee platform and the EU’s EFSD+ platform are important steps toward creating spaces for collaborative efforts to identify and promote available guarantees. However, as some organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy in philanthropy and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) or Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in the MDB sector, become experts in this area, the key to scaling up credit enhancements and collaboration will be to connect all stakeholders. This means aligning project opportunities from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with the technical support offered by those who are already experienced in these solutions to help those who are less familiar. An up-and-coming initiative addressing this is Scaling Capital for Sustainable Development (SCALED), who is developing a platform that will streamline the entire development and management process of public-private cooperation for blended finance transactions.

For blended finance to scale and contribute meaningfully to closing the sustainable financing gap, investors must deepen their understanding of these credit enhancement techniques and integrate them into their investment toolkits. By doing so, they can consolidate pools of catalytic capital, improve investment terms, and accelerate progress toward global sustainable development goals. Ultimately, the standardization and replication of proven blended finance models, supported by robust credit enhancements and complemented by technical assistance, will be key to reduce the time-to-market for new vehicles as well as encourage the entry of new participants into the landscape of development finance and achieving lasting impact in EMDEs63.

1. Environmental Finance (2025) https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/strategic-asset-allocation-in-emerging-markets.html

2. UNCTAD based on Refinitiv, reflecting the arithmetic average of ratings by S&P, Moddy’s & Fitch,

https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gds2024d3_en.pdf

3. IFC (2024). IFC 2024 Annual Report Financials, Table 5 Long-Term Finance and Short-Term Finance Commitments.

https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2024/ifc-annual-report-2024-financials.pdf

4. Combining the World Bank, IFC, and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA),

5. Institute of International Finance, (2023). Scaling Blended Finance for Climate Action – Perspectives from Private Creditors.

6. 4P Secretariat, (2025). Reforming the international financial architecture: where do we stand?

https://focus2030.org/IMG/pdf/focus2030_4p_follow_up_report_2025.pdf

7. OECD, United Nations development program. (2021). Closing the SDG financing gap in the covid 19 era.

https://dwgg20.org/documents/oecd-undp-closing-the-sdg-financing-gap-in-the-covid-19-era/

8. OECD, (2025). Official Development Assistance. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/official-development-assistance-oda.html.

(2025) Reforming the international financial architecture: where do we stand? Progress report on the Pact for Prosperity, People and the Planet (4P)

https://focus2030.org/IMG/pdf/focus2030_4p_follow_up_report_2025.pdf

9. Convergence, (2025). State of blended finance 2025 report. https://www.convergence.finance/resource/state-of-blended-finance-2025/view.

10. Data as of end December 2024.

11. Institute of International Finance (IIF), (2023). Scaling Blended Finance for Climate Action – Perspectives from Private Creditors.

12. Amundi, (2025). A Framework for Structuring a Blended Finance Fund, Roncalli, T. Lekhel, A., Ben Slimane, M., Dumas, JM.

https://research-center.amundi.com/article/framework-structuring-blended-finance-fund

13. G20, (2024). G20 Roadmap towards better, bigger and more effective MDBs.

15. Attridge, S., Getzel, S. and Gregory, N., (2024). Trillions or billions? Reassessing the potential for European institutional investment in emerging markets and

developing economies. https://odi.org/documents/9061/Working_paper_-_trillions_or_billions-full_text_23.05.pdf

16. —such as pension funds and insurance companies—

17. Morgan Stanley, (2021). Emerging Markets Allocations: How much to own?

https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_howmuchtoown_us.pdf

18. Attridge, S., Getzel, S. and Gregory, N., (2024). Trillions or billions? Reassessing the potential for European institutional investment in emerging markets and

developing economies. https://odi.org/documents/9061/Working_paper_-_trillions_or_billions-full_text_23.05.pdf

19. Drijkoningen, R., Urquieta, G., (2024). CIO Weekly Perspectives – Re-Emerging Markets.

https://www.nb.com/en/global/insights/cio-weekly-perspectives-re-emerging-markets

20. Erol Madan, S., (2024) How can we unlock infrastructure finance at scale for developing countries?

https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/how-can-we-unlock-infrastructure-finance-at-scale-for-developing

21. Mohamed AlMulla, M., (2025). Why capital flows have the potential to change the economic status quo.

22. Amundi, (2024). Emerging Markets charts and views: Gearing up ahead of US elections and policy easing.

23. Choi, S., Medina Cas, S., (2017). Transparency Pays: Emerging Markets Share More Data. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2017/07/07/transparency-pays-emerging-markets-share-more-data#:~:text=We%20have%20tried%20to%20quantify,the%20transparency%20improvements%20are%20made.

24. Erol Madan, S., (2024) How can we unlock infrastructure finance at scale for developing countries?

https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/how-can-we-unlock-infrastructure-finance-at-scale-for-developing

25. Attridge, S., Getzel, S. and Gregory, N., (2024). Trillions or billions? Reassessing the potential for European institutional investment in emerging markets and

developing economies. https://odi.org/documents/9061/Working_paper_-_trillions_or_billions-full_text_23.05.pdf

26. Erol Madan, S., (2024) How can we unlock infrastructure finance at scale for developing countries?

https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/ppps/how-can-we-unlock-infrastructure-finance-at-scale-for-developing

27. the ‘matching adjustment’ under Solvency II only allows insurers to discount long-term liabilities favorably for investment-grade assets, often excluding many

EMDEs with lower sovereign ratings.

28. Even if EM investments align with European sustainability standards, they may not contribute to some KPIs. For example, the Green Asset Ratio (GAR) assesses

the proportion of EU green taxonomy-aligned assets. Green investments outside the EU are excluded from the numerator of the GAR calculation but included in the

denominator, leading to a GAR of 0% to some European DFIs, no matter their strong sustainable finance portfolios.

29. GEMs is the largest credit risk database for emerging markets, designed to drive investment to developing countries by helping investors better assess the risks

30. Galizia, F., and Lund, S., (2025). Are emerging market risks for private investors overstate? What the data shows.

31. Galizia, F., and Lund, S., (2024). Reassessing Risk in Emerging Market Lending: Insights from GEMs Consortium Statistics.

https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2024/reassessing-risk-in-emerging-market-lending.

32. Lindner, P., Prasad, A., Masse, J., (2025) The Scalability of Credit Enhanced EM Climate Debt: What Role Can Guarantees, Collateralization, Securitizations,

and Investment Funds Play? https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2025/01/10/The-Scalability-of-Credit-Enhanced-EM-Climate-Debt-What-Role-Can-Guarantees-560546

Many climate investments consist of large, capital-intensive projects, like solar plants, wind farms, or dams. Generally, the sponsors of longterm

projects will prefer long-term funding at low rates. With the bond markets generally much better equipped to provide long-term funding compared to bank

loans, this paper will focus on credit enhancements for bonds, if not stated otherwise.

33. The positive effects of guarantees for loan provision to households and small firms is discussed in Serebrisky, T., Suarez-Alemán, A. and Pastor, C. (2018).

34. In the U.S., investment grade bonds are usually unsecured. They are more frequently used by utilities (often in the form of “first mortgage bonds”)

and in the high yield bond sector. Empirical studies found that most bank loans are secured. Pozzolo (2002).

35. It should be noted that having a security/recourse to assets at the instrument level does not cover all types of risks (eg sanctity of contract, legal stability,

political risk) as opposed to other types of guarantees and credit-enhancement solutions (that would involve the use of escrow accounts, or similar schemes,

and be established in well-recognized governing law.

36. Amundi - Roncalli, T. Lekhel, A., Ben Slimane, M., Dumas, JM, (2025). A Framework for Structuring a Blended Finance Fund.

https://research-center.amundi.com/article/framework-structuring-blended-finance-fund

37. Institute of International Finance, (2023). Scaling Blended Finance for Climate Action – Perspectives from Private Creditors.

38. Catalytic first-loss capital has three main features: (i) identified party (or Provider) that will bear the first losses; (ii) the funding is catalytic, meaning it will

improve the Recipient(s) risk-return profile as the capital catalyzes the participation of investors that otherwise would not have participated; and (iii) the capital

is purpose driven by channeling commercial capital to certain environmental and/or social outcomes. GIIN (2013), Issue Brief: Catalytic First Loss Capital.

39. The lack of a credit rating will prevent a re-rating of the mezzanine and the senior tranches in case significant credit losses lead to a depletion of the equity

tranche, or if a notable worsening of the credit worthiness of the underlying debt occurs.

40. Green, Social, Sustainable Bonds

41. Lindner, Peter, Ananthakrishnan Prasad, and Jean-Marie Masse. 2025. “The Scalability of Credit-Enhanced EM Climate Debt.” IMF Working Paper 2025/002,

International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

42. World Bank, (2024), A Focused Assessment of the International Development Association’s Private Sector Window: An Update to the Independent Evaluation

Group’s 2021 Early-Stage Assessment. Independent Evaluation Group. Washington, DC: World Bank.

43. Convergence, (2025). State of blended finance 2025 report. https://www.convergence.finance/resource/state-of-blended-finance-2025/view.

44. Habbel, V., E. Jackson, M. Orth, J. Richter and S. Harten (2021), “Evaluating blended finance instruments and mechanisms: Approaches and methods”,

OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers, No. 101, OECD Publishing, Paris.

45. Leverage ratios are defined as the amount of commercial capital mobilized by each dollar of concessional capital, where commercial capital includes capital

deployed by private, public (e.g., Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs)) and philanthropic investors at market rates.

https://www.convergence.finance/news/4cC8kVJXvOFZDVxGQ6HLNH/view

46. Moehrle, C. (2024). Blended funds: don’t get obsessed with leverage.

47. Sustainable Markets Initiative and Investor Leadership Network. (2024) Blended Finance Best Practice Booklet: Case Studies and Lessons Learned.

49. Horrocks, P. et al. (2025), “Unlocking local currency financing in emerging markets and developing economies: What role can donors, development finance

institutions and multilateral development banks play?”, OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers, No. 117, OECD Publishing, Paris,

https://doi.org/10.1787/bc84fde7-en, https://oecd-development-matters.org/2025/03/20/beyond-hard-currency-a-new-approach-for-development-finance/

50. https://www.convergence.finance/blended-finance

51. World Bank Group – MIGA. (n.d.) Political Risk Insurance. https://www.miga.org/political-risk-insurance

52. Sonenshine, R., Aboulhosn, A., (2025). Impact of political risk on emerging market risk premiums and risk adjusted returns, Research in International Business and Finance,

Volume 73, Part A, 2025,102573, ISSN 0275-5319, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2024.102573. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0275531924003660)

53. U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, (2023). Capital Mobilization Impacts Resulting from DFC’s Political Risk Insurance Product – Impact

Assessment Report. https://www.dfc.gov/sites/default/files/media/documents/McKinsey%20PRI%20Capital%20Mobilization%20Impact%20Assessment.pdf

54. S&P, Marsh, (2024). Unlocking the Power of Political Risk Insurance.

55. International Finance Corporation (IFC), (n.d.). Structured and Securitized Products – Partial Credit Guarantees.

http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/176221620716778496/pdf/Partial-Credit-Guarantees.pdf

56. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), (2022).

https://www.ebrd.com/home/news-and-events/news/2022/ebrd-invests-in-scatec-green-bond.html

57. Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), (2025).

58. https://infracredit.ng/about-us/

59. Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), (2025). Energizing Private Capital: Innovations in Guarantee Offerings for Climate Finance.

60. https://www.blendedfinance.earth/about

61. Blended Finance Taskforce, (2023). Better Guarantees, Better Finance.

62. Whiting, K., (2024). Climate finance: What are debt-for-nature swaps and how can they help countries?

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/04/climate-finance-debt-nature-swap/

63. Sustainable Markets Initiative, Investor Leadership Network, (2025). Blended Finance Best Practice: Case Studies and Lessons Learned.