Summary

Executive summary

With development financing needs outpacing available resources, attracting private capital into social and environmental projects in risky markets (e.g., emerging markets) is vital. We believe that Blended Finance (BF) offers a strategic solution. Specifically, this investment approach involves the public sector leveraging private money to finance projects focused on achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and addressing climate change. Institutional investors are enticed to participate in these projects, which may initially appear too risky for them. BF is widely employed by public sector sponsors, such as development finance institutions (DFIs) and multilateral development banks (MDBs), whose mandates are to serve public interests (e.g., reducing poverty).

However, there are challenges in designing effective BF solutions. These solutions need to offer private investors market-based, risk-adjusted returns while, at the same time, move beyond being bespoke solutions to scalable ones. This is necessary if BF is to no longer remain a niche within the broader field of sustainable finance.

At the Amundi Investment Institute, we have recently focused our research on the modelling of structured BF vehicles, with particular emphasis on credit risk analysis, tranche calibration, portfolio diversification, cash flow structuring and risk premium evaluation. In particular, we look at how to reconcile diverse investors’ objectives and achieve optimal structures in junior-senior tranche vehicles1. This involves maximising the leverage ratio (i.e., the amount of private sector capital relative to public sector capital) for the sponsor (e.g., junior investor, DFI), managing the concessionality premium and ensuring the safety of the senior tranches2.

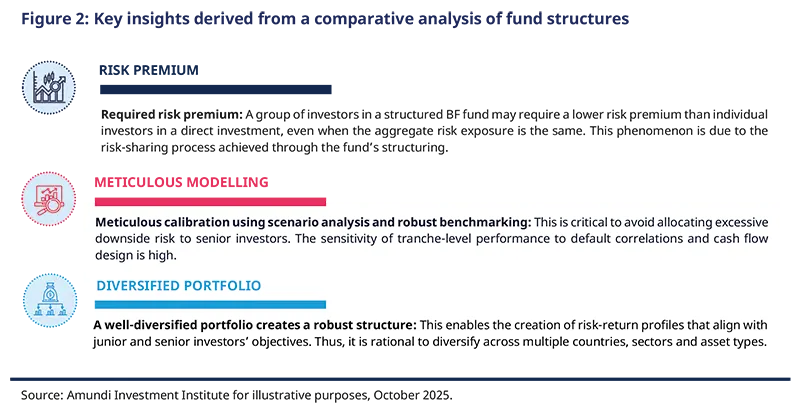

Several key insights emerged from our analysis. Firstly, the risk premium required (i.e., the price of ensuring an investment is attractive to private investors) by a structured BF fund may be lower than that required by a direct investment. This is due to the risk-sharing process embedded in the structure of the fund3. Secondly, to avoid allocating excessive risk to senior investors, it is critical to use scenario analysis and robust benchmarking in modelling. Finally, to create risk-return profiles that align with investors’ objectives, it is important to have a well-diversified portfolio.

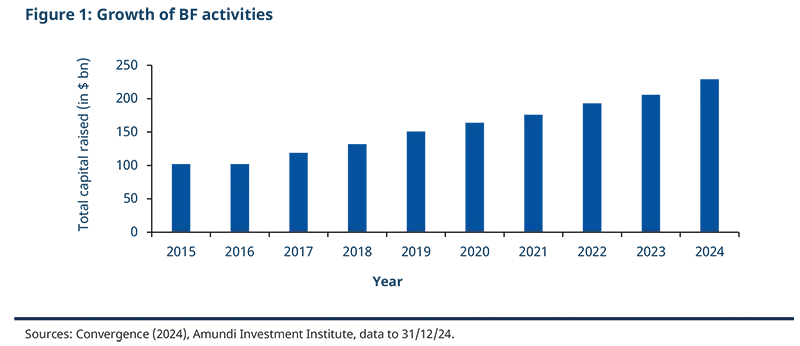

Looking ahead, there is a notable financing gap between the BF market size ($230 billion) and the estimated energy transition costs ($275 trillion between 2021 and 2050)4. To close this gap, products’ risk sharing and scalability need to be improved, while collaboration across public and private sectors becomes increasingly important. Only then can BF reach its full potential.

Blended finance offers private investors a unique opportunity to deploy capital that achieves both financial returns and sustainable impact. Unlocking this capital is critical in ensuring that emerging markets can join the energy transition.

| VINCENT MORTIER Group CIO, Amundi | MONICA DEFEND Head of Amundi Investment Institute |

The increasing relevance of blended finance for private investors

The BF market size is small ($230 billion), with growth restricted by product complexity, limited availability of investable assets (e.g., emerging market corporate bonds), incremental regulatory requirements and the projects’ long investment horizons. These restrictions have ensured that annual BF commitments between 2023 and 2025 only averaged approximately $15 billion. This is insufficient when compared to the estimated $4 trillion in annual investment required to achieve the SDGs5.

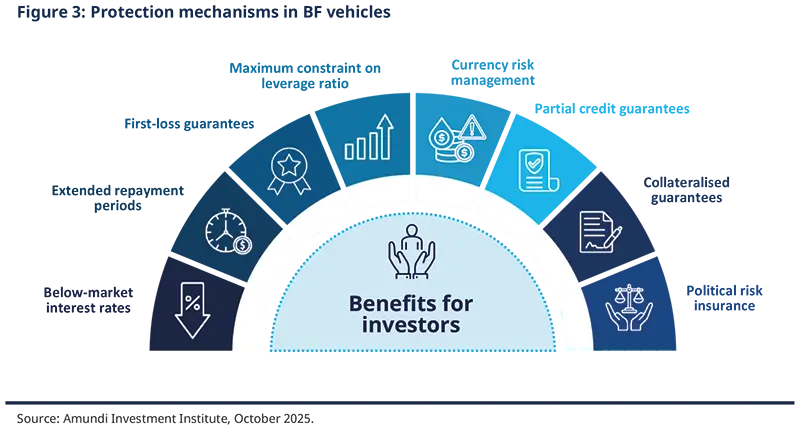

Several measures are expected to promote higher growth going forward (e.g., the Global Green Bond Initiative, the COP 29 UN Climate Conference agreement), while the availability of scalable layered fund structures that include credit enhancements (e.g., first-loss guarantees, political risk insurance) is increasing6. This is essential in helping to mitigate perceived risks. Additionally, currency risk mitigation strategies provide protection from the impact of currency fluctuations that can erode returns, especially when revenues are in local currencies, but obligations are in hard currencies. Furthermore, collaboration across stakeholders is rising, which will facilitate the design of standardised structures and knowledge sharing. These factors are contributing to aligning investment opportunities with investors’ risk preferences.

The future of blended finance hinges on standardisation, scalability and collaboration. For the market to attract institutional investors at scale, defining and agreeing on optimal product structures will be essential.

Everyday challenges in designing solutions

Overcoming structuring challenges when working with DFIs and MDBs

Adnane LEKHEL |

A key challenge is managing the necessary balancing act between these institutions’ mandates, timelines and risk appetites as well as those of private sector investors. In our view, DFIs and MDBs bring tremendous value to transactions. This is not only through their development mandates and roles in mobilising capital for high-risk projects but also due to their deep understanding of emerging markets. However, these organisations tend to err on the side of caution, as they aim to safeguard public capital. Furthermore, their processes are complex, designed to align with governance frameworks as well as policy goals. This complexity can constrain the potential for solutions, even when there are strong developmental rationales.

Encouragingly, DFIs and MDBs are now exploring more flexible BF models to attract private capital, especially in underserved or very low-income markets. Increasingly, these models are helping to push the boundaries of more traditional frameworks. We believe the key to achieving greater flexibility is the emergence of more platforms where public and private stakeholders can collaborate.

Ultimately, we see our role as being innovative in designing solutions that align institutional mandates with private commercial objectives while also safeguarding projects’ financial health and development impacts. Essentially, we strive towards stakeholders’ needs being met, capital being unlocked and transformative outcomes being achieved.

A view into future obstacles for the development of BF

Jean-Marie DUMAS |

One of the largest hurdles for the future of BF is ensuring that the developmental aspect of a transaction is not viewed as an additional risk that private capital must bear without proper compensation. To avoid this, DFIs and MDBs need to absorb risks or provide incentives that de-risk investments and make them commercially viable. This is why pricing mechanisms and capital stack designs (e.g., junior-senior tranches) are so important. They must reflect each party's actual contribution and align with shared KPIs so that both public and private stakeholders are incentivised to pursue the same goals.

A second major challenge is moving beyond purely bespoke solutions. By nature, BF transactions often require customised structuring due to their thematic focus (e.g., climate, biodiversity) or the use of specific instruments (e.g., guarantees, technical assistance facilities, multi-layered tranching). However, this high degree of customisation can limit replicability and scalability. Furthermore, expertise in structuring BF funds is concentrated among a few DFIs and MDBs, creating bottlenecks in market development. To enable scalability, these institutions must share their knowledge and collaborate with a wider range of stakeholders to design the next generation of standardised BF models that are sufficiently flexible to meet impact goals.

Insights into blended finance structures

Interview with Thierry Roncalli (Head of Quant Portfolio Strategy, Amundi Investment Institute) on insights from his recent paper “A Framework for Structuring a Blended Finance Fund” and Elodie Laugel (Chief Responsible Investment Officer, Amundi). |

Thierry, you have developed a framework for assessing structured BF funds. What, in your opinion, are their critical components?

Two critical components are the concessionality rate and the leverage ratio. The concessionality rate measures how much a loan’s terms are more favourable than market terms. This can include below-market interest rates, longer repayment periods, or grace periods during which the principal or interest payments are deferred. These flexible terms can be tailored to the financial circumstances of the borrower, making debt servicing more manageable. Thus, concessional capital plays a critical role in de-risking development projects by absorbing part of the financial risk.

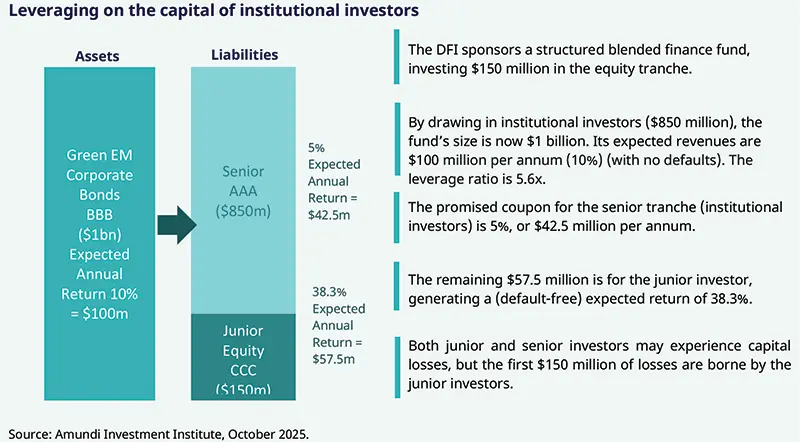

Turning to the leverage ratio, this is the amount of private sector (i.e., institutional) capital divided by the public sector or sponsor (e.g., DFIs) capital. A DFI’s objective is to maximise the leverage ratio. As these public organisations operate with limited annual budgets, achieving a high leverage ratio allows them to support a greater number of projects than they could otherwise fund on their own.

Thierry, in your view, what is an optimal structure for a BF fund?

An optimal structure aligns the different financial objectives of the two types of investors. While a DFI’s objective is to maximise the leverage ratio, institutional investors want to safeguard the senior tranche. So, although these different investors may share the same impact-oriented objectives, their financial objectives diverge.

To maximise leverage, the DFIs (i.e., junior investors) absorb higher risks so that senior tranches are better protected. For example, DFIs can offer first-loss guarantees, agreeing to cover the first X amount of losses. Also, as the risk borne by the senior tranche investors increases with higher leverage, optimal structures should incorporate a constraint that reflects their maximum acceptable risk level. These risk buffers help those investors achieve investment-grade ratings, enabling them to participate in the senior notes.

Box 1: How does BF work? A DFI (e.g., the World Bank, the European Investment Bank) may want to promote the market for emerging market green bonds. To examine various solutions, we assume that the DFI has a $150 million fund, and the green bonds’ expected return is 10%.

|

Thierry, what are the reasons behind the differences in BF funds’ structures?

One reason for differences is that asset portfolios do not have the same risk profiles. Factors such as maturity, portfolio diversification, asset concentration and the nature of the underlying credit risk (e.g., crossover bonds versus high-yield assets) can influence the effectiveness and resilience of a structured finance vehicle7.

A second notable difference lies in the relative sizes of the senior and junior tranches within the fund’s structure. There is a trade-off between the junior tranche’s size and the credit rating of the senior tranche. A larger junior tranche lowers the leverage ratio compared to funds with smaller junior tranches. This can improve the senior tranche’s credit rating, making the opportunity more attractive to institutional investors.

Finally, different investors’ preferences can influence fund structures. Not only are those of institutional investors different from those of the DFIs, but also it can be assumed that institutional investors’ preferences across two different BF funds are not the same.

Thierry, in comparing BF fund structures, what are the critical characteristics to consider?

We determined a framework that can be used for comparing fund structures. Firstly, robust modelling of the credit risk within the asset portfolio is critical. In particular, the risks to a senior tranche’s performance need to be examined, given that institutional investors are subject to credit rating constraints. Cash flow analysis is also an important pillar in fund modelling. This analysis on the asset side is straightforward, but on the liability side, there are differences in tranche payment rules, performance triggers and protection mechanisms. All these factors significantly impact the risk-return profile for investors. Finally, we established that the senior tranches’ performances are sensitive to tail risks; hence, it is vital to examine the impact of default correlation on portfolios' loss distributions. To capture regional and sectoral risk dynamics, we used multi-factor models, which allow for an in-depth risk analysis across portfolios.

Thierry, what strategies can be used to reinforce a junior-senior tranche structure?

If the default correlation among bond or project issuers is high, or diversification is poor, strategies can be used to strengthen the structure. The leverage ratio can be reduced by increasing the junior tranche's total exposure, while the senior tranche’s investments could be limited to less than 60%. Protection mechanisms are also used, such as loss carry-forward techniques or dividend sponsorship8.

In addition, a portfolio’s systematic risk can be high compared to its idiosyncratic risk, especially when it includes both crossover bonds and pure high-yield bonds. This reduces the benefits of diversification, making it difficult to create two distinct risk-return profiles. In such cases, a mezzanine tranche can act as a buffer between the junior and senior tranches, thereby improving risk allocation. Finally, there are effective guarantees and risk transfer mechanisms available to mitigate perceived investment risks in emerging markets (see Box 2)9.

Box 2: Credit enhancements and risk transfer mechanisms Supporting our research on optimal BF vehicles, we also wrote a paper examining the strengths and weaknesses of credit enhancements and risk transfer mechanisms that exist at both the portfolio and transaction levels, of which there are several types. To start, DFIs not only offer first-loss guarantees on liabilities but also provide them on funds’ assets. Partial credit guarantees (PCGs) are used as well, offering transaction-specific protection, while institutional investors can agree to collateralised guarantees where they supply all the funding, provided their exposure to potential losses are limited. Turning to insurance products, political risk insurance (PRI) can be obtained to mitigate risks associated with war and civil disturbances. Furthermore, this insurance can be layered alongside PCGs, allowing investors to address both political and credit risks within a single transaction. Such a combination has proven critical in sectors like infrastructure, renewable energy and financial inclusion. The success of these guarantees depends on correctly determining the size they need to be to sufficiently de-risk the portfolio and ensure the entire structure functions effectively. A survey from the Institute of International Finance (IIF) indicates that private creditors view them as one of the most effective components of BF structures. For them to alleviate risks, they must be perceived as credible and independent of the borrower’s influence.9 The aim of the paper is to create awareness of credit enhancements which, in turn, will enable informed decisions to be made about BF opportunities, including their alignment with investors’ preferences (How can investors lean into blended finance structures: demystifying credit enhancements). |

Elodie, how can currency risk be addressed?

Currency risk can undermine a portfolio’s performance. Hence, market-driven solutions have emerged to address this challenge, such as The Currency Exchange Fund (TCX). Established by a consortium of DFIs, impact investors and multilateral banks, TCX provides hedging instruments that allow investors to transfer local currency risk off their balance sheets. Importantly, TCX prices the hedge to reflect the true economic cost of carrying emerging market currency exposures, rather than speculative market pricing. These instruments play a role similar to credit enhancements.

Elodie, are there other challenges beyond risk modelling, tranche design and portfolio diversification?

Other important challenges include the need to effectively manage governance risks, enhance transparency and enable market growth through better liquidity and regulatory frameworks. Meeting these challenges will require collaboration between DFIs, asset managers and regulators. In addition, all stakeholders in project opportunities in low- and middle-income countries need to be connected with those who are experienced in creating these solutions.

Initiatives like the World Bank’s new guarantee platform and the EU’s EFSD+ platform are steps toward creating spaces for digital cooperation.10

Layered fund structures provide a proven framework for public-private partnerships to mobilise large-scale investment. Credit enhancements and currency risk mitigation mechanisms are critical levers to unlock financing for the SDGs in emerging markets.

Finally, Elodie, is there an overlap between BF and impact investing?

BF has an overlap with impact investing. BF is a structured approach that uses public and private funds to raise extra capital for development projects, whereas impact investing encompasses a wider range of strategies to achieve positive environmental and social outcomes, along with financial returns. Many BF deals qualify as impact investments, but private investors may not be willing to take on the same amount of risk or prioritise impact to the same extent as public investors.

1. A junior-senior tranche structure divides a pool of assets into different risk levels, with senior tranches being the least risky and junior tranches the riskiest. Senior tranches are paid first in case of defaults, while junior tranches are the first to absorb losses.

2. The concessionality premium is the degree to which the financial terms on offer are more favourable than market-based terms.

3. In comparison to a direct investment, the lower risk premium required by a BF fund does not imply lower expected performance.

4. McKinsey & Company, “The net-zero transitions”, January 2022. McKinsey & Company estimated that capital spending on physical assets for energy and land use in the net-zero transition would amount to about $275 trillion. Convergence (2024), “State of Blended Finance 2024”, Report, April 2024.

5. Convergence (2024), “The state of blended finance 2024”, Convergence Blended Finance. Mazzucato, M. (2025a),“Reimagining financing for the SDGs: From filling gaps to shaping finance”, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Policy Brief No. 170, Special Issue, United Nations.

6. A coalition of DFIs and MDBs makes up the Global Green Bond Initiative. The pooled vehicle is backed by a guarantee from the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus. The COP 29 UN Climate Conference (November 2024) resulted in 200 countries agreeing to triple finance to developing countries, reaching USD 300 billion annually by 2035.

7. Crossover bonds, also known as crossover credit, are bonds that sit on the borderline between investment-grade and high-yield credit ratings.

8. A capital loss carry-forward is the process of claiming the balance of a capital loss deduction in future years when it exceeds the annual limit in the first year. A dividend sponsorship allows investors to automatically reinvest their cash dividends into purchasing additional shares in the company.

9. Institute of International Finance, “Scaling blended finance for climate action – perspectives from private creditors”, July 2023.

10. The €13 billion EFSD+ Open Architecture Guarantees allow investors to finance projects in more challenging markets by assuming the risks of more unstable environments. The World Bank Group launched a new guarantee platform on July 1, 2024, to streamline product offerings and maximise the limited capital available for development in emerging markets and developing economies.