President Trump’s tariff announcements have rattled the previously dominant US financial markets, putting pressure on Treasury yields amid fears of slower growth and rising inflation.

Recently, the difference in yield that investors expect for holding Treasuries compared to swaps has increased significantly, signalling a perceived higher risk of holding Treasuries.

The end of US financial market exceptionalism is by no means guaranteed, but we believe it is increasingly important to enhance diversification also in the sovereign debt space. In this regard, European government bond markets are a valuable option.

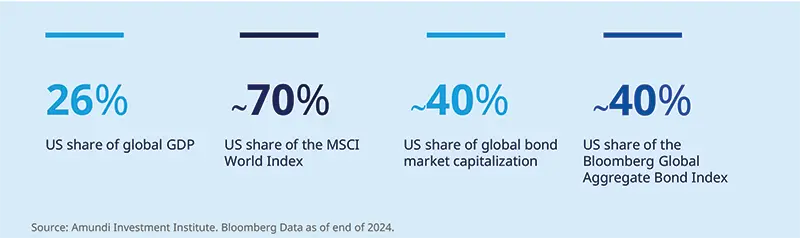

Until very recently, the US dollar (and US capital markets) seemed to reign supreme. The dollar has increasingly dominated as the currency of global transactions. Swift payments denominated in dollars rose from just over 30% of the total in early 2010 to an all-time high of 50.2% in January 2025. And more and more, US equity markets have been where the world stores its wealth. As a percentage of the global index, the MSCI US index rose from 37% in 1995 to 74% at the end of last year. Look more closely, however, and the dominance of US financial markets seems less assured. The US Treasury market, in particular, is showing signs of pressure.

What is happening in the US Treasury market?

President Trump's unexpected announcement of unprecedently large tariffs on April 2 sent shockwaves through the economy, leading to soaring financial market volatility. Initially, Treasury yields fell due to recession fears, but longer-term yields quickly rebounded as investors anticipated higher inflation and started to price in higher risks. The 10-year yield surged from below 4% to 4.5% in just a few days, while the 30-year yield rose to 5%.

The dominance of US financial markets seems less assured. The US Treasury market, in particular, is showing signs of pressure.

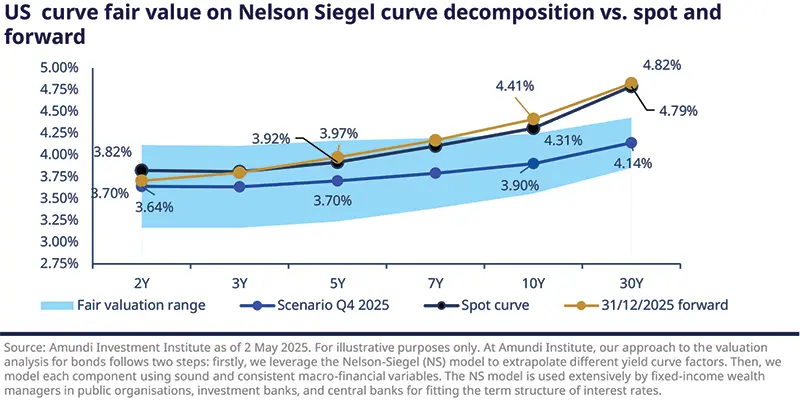

According to our model, US 10- and, in particular, 30-year Treasury yields are above their fair value.

This is not the first time US Treasuries have come under pressure since the US presidential election in November. Indeed, our fair value model of US 10-year yields has shown them to be undervalued at several points over the past five months and it suggests that they may be undervalued now. We see US 10-year yields staying at 4.3%, in line with current market levels, due to the balancing pressures of weak growth and sticky inflation.

Why are Treasuries under pressure?

To assess why Treasury yields are under pressure, we should look at the main factors influencing changes in nominal yields:

expectations of real economic growth, which account for approximately two-thirds of the changes in nominal yields;

inflation expectations, represented by the break-even rate, which contribute around 20%;

and the intrinsic quality of Treasuries, indicated by the swap spread, which accounts for about 10–15% of the changes in nominal yields.

In focus: understanding the asset swap spread

The intrinsic quality of US Treasuries can be assessed using the swap spread. This compares the interest rates (yields) of Treasuries with the rates on swaps* that have the same maturity.

- Positive Swap Spread: Treasuries yield less than the swap rate. Investors are willing to accept lower yields on Treasuries than on swaps, due to the perceived safety and stability of Treasuries.

- Negative Swap Spread: Treasuries yield more than the swap rate. Since 2020, when swaps started using SOFR as their variable rate, this has generally been the case. Investors have demanded a higher yield from Treasuries due to concerns about excessive supply or weakening demand.

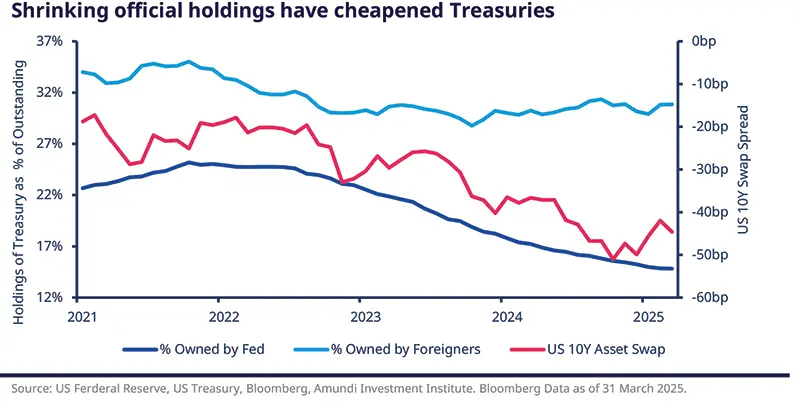

Recently, the increase in yield that investors require for holding Treasuries relative to swaps has increased significantly. From 2021 to 2023, the asset swap rate was between -15 basis points (bp) and -35 bp. In early April 2025, this rate dropped to an average of -55 bp, meaning investors are demanding an even higher yield for holding Treasuries relative to swaps.

*An interest rate swap is a financial agreement between two parties to exchange interest rate payments on a specified principal amount over a set period. Typically, one party pays a fixed interest rate while the other pays a variable rate based on a benchmark like the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR).

In April, the swap rate—the spread between Treasury yields and interest rate swaps—widened, raising concerns about market dysfunction and the safe-haven role of US Treasuries. We believe Treasury yields will continue to rise against swaps for two reasons.

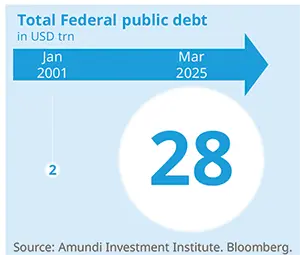

Supply will likely continue to increase. The US has run a fiscal deficit since 2002, but the shortfall ballooned during the COVID years. Federal debt as a percentage of GDP has more than doubled since the start of the century, rising from 56% in 2000 to 124% at the end of last year. Bigger deficits necessarily mean more bond issuance. The US Treasury may well continue to increase bill issuance relative to bonds, but we expect Treasury yields to rise relative to swaps across the curve.

|

Demand for US Treasuries may also continue to decline, particularly from two types of actors:

- The Fed: At its peak of the quantitative easing program in mid-2016, the Fed held $6.3 trillion of Treasuries on its balance sheet. As quantitative easing has become quantitative tightening, that number has shrunk, falling to $4.2 trillion at the end of March.

- Big foreign holders, typically central banks and sovereign wealth funds: Treasuries held by these participants have not fallen in nominal terms but have grown from just over $1 trillion in 2001 to more than $8 trillion in March this year. Yet because this has been outpaced by the growth of the Treasury market, the percentage held by these investors has declined from a peak of 56% in mid-2008 to just over 30% today.

For the time being, the move to a more negative swap spread seems to have been driven by the decline in Fed holdings (see chart below).

It is easy to imagine, however, that if big foreign investors reduce their holdings, Treasury yields could rise even more relative to swap rates. In the absence of a fall in the swap rate, this could push US nominal yields higher.

How to navigate this phase of uncertainty in bonds

While we don’t have clear evidence of a massive selloff of US debt by foreign investors, we believe it’s key to monitor swap spread dynamics going forward for at least two reasons:

- First, Treasuries still represent the risk-free rate used to price many dollar-denominated assets, such as corporate bonds. A continuation of an environment in which US Treasuries remain under pressure can create discrepancies in relative pricing.

- Second, if Treasuries lose their lustre as a store of value, this could provoke a flight of capital out of the US–and given the size of the US Treasury market, the ramifications for currency markets could be very significant. The quadrupling of the trade-weighted dollar’s value since 1978 could reverse, causing ripples throughout the global financial system.

If US Treasury yields rise due to global inflation pressure or fall due to weak global growth, government bond markets are likely to follow suit. However, if US Treasury yields rise because of worsening credit quality, then other government bond yields will not necessarily move in correlation with US yields. Indeed, as money flows out of the US government bond market, it will need to go elsewhere, and correlations between swap spreads (and yields) could well become more negative.

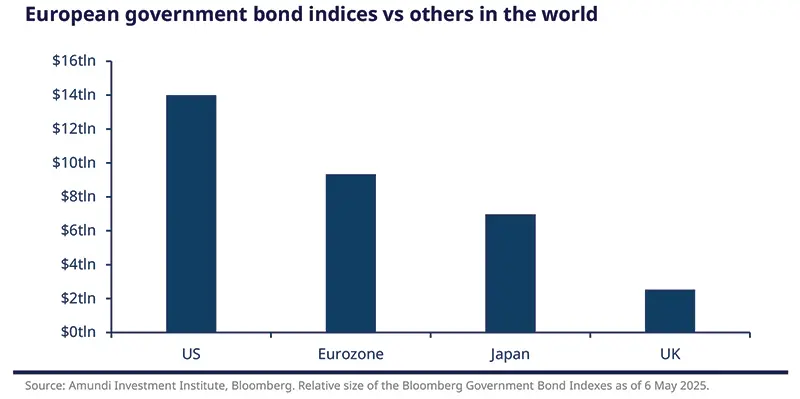

The second-largest government bond market after the US is the Eurozone. It is currently around two-thirds the size of the US market, while the Japanese and UK markets are half and slightly less than one-fifth the size of the Treasury market, respectively. So, although Europe is smaller and contains a range of countries, we still believe it is the most likely to benefit from flows out of US Treasuries into other global bond markets.

In conclusion, while the end of US financial market exceptionalism is by no means guaranteed, we believe it is increasingly important to enhance diversification even in the sovereign debt space.

The European government bond market may offer a valuable alternative to the US market, given its similar range of maturities and the fact that it is only 20% smaller than the US Treasury market.