Summary

Executive Summary

The Covid-19 crisis can be considered a turning point for social issues: it has put global socio-economic inequalities in the spotlight and made them more concrete than ever before. It has also clearly shown the tragic effects, from an economic and societal perspective, that systemic shocks can have on unequal, non-resilient societies.

On the one hand, it is generally accepted that an excessive increase in inequality represents a real threat to financial stability and to economic growth. On the other hand, however, there is no real consensus or a ready-to-use framework for social risks at a microeconomic level of analysis, i.e. which socially-related factors have the capability to materially affect companies.

In this exploratory framework, Amundi has identified several social risks at a company level that can originate from the relationships between the company itself and its most important stakeholders, namely employees, consumers, society at large and regulatory authorities.

For each of these stakeholders, some relevant social risks were identified: indeed, they were proven to have a material impact on the financial value of companies. Overall, while transition and physical are the generally agreed-on climate change risks, in the case of the social pillar, they seem to mostly relate to the transition towards a “fairer” economy: employees’ need for “decent work” contracts, changing consumer behaviours and expectations, overall societal demands for companies to contribute fairly to the communities they operate in, increasing regulations in terms of corporate income taxes, human rights due diligence, etc.

In this unprecedented context, the materiality of social risks is expected to increase. Moody’s estimated that US$8trn of the total debt it rates is subject to material social risks, i.e., four times the amount exposed to climate change risks, and this figure is expected to be even larger in the years to come. Investors should thus start integrating social risks along their whole investment value chain, from analysis to engagement and voting, in order to be prepared for their increasing materiality and impact on a company’s financial performance.

The Covid-19 crisis has been a turning point for inequalities

The issue of social inequality has been discussed for years by academics and is constantly a hot topic among researchers but also within the general public, as proven for instance by the remarkable success of Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the XXI Century” in 2015. Several trends have coexisted in past decades, shedding light on the complexity of the topic, and the Covid-19 crisis is likely to accelerate any pre-existing trajectories for inequality.

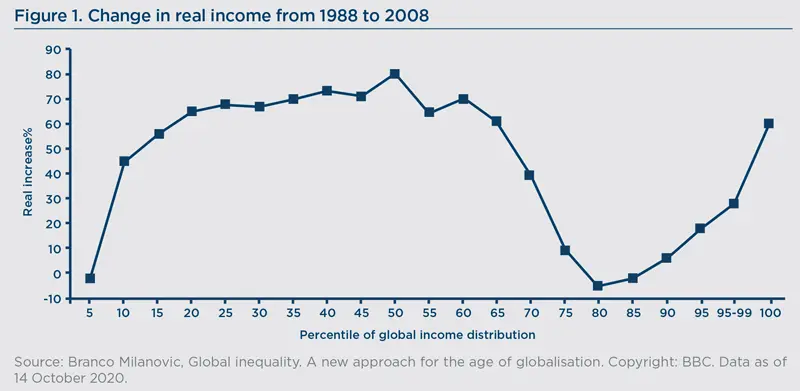

On the one hand, the recent growth episode since the 1980s has led to a decrease in global income inequality overall, when measured in relative terms. The remarkable economic development of countries such as China and India is identified as the main driver of this decline, leading to an improvement in living conditions for the poorest half of the population. In fact, the share of the global population living in extreme poverty has come down from 37% in 1990 to 10% in 2015.1 However, this overall convergence is not evenly distributed, and the differences between countries and regions are still extensive. In 2020, the average income of people living in Northern America was 16 times higher than that of people in sub-Saharan Africa.2

On the other hand, the growth of income inequality within countries has mainly involved developed liberal democracies. The lion’s share of the recent growth episode was taken by the top 1%, leaving little on the table for the middle class. Across OECD countries, the richest 10% earn, on average, 9 times as much as the bottom 10%. Furthermore, the GINI coefficient – one of the most popular measures of income inequality – experienced a 10% hike between the mid-1980s to 20183. The increase was especially pronounced in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States.

On top of this, Covid-19, like all major pandemics over the last century, is likely to push inequalities higher.4 Developed countries with older populations have been hit hardest in terms of mortality, despite having better health systems, higher incomes and better preparedness. Lower educated people, as well as young people and women, also suffered more significantly from job and revenue losses. Overall, the pandemic has placed social issues in the spotlight, with access to healthcare and social protection being a fundamental concern for governments to support households and companies in the short-term.

The Covid-19 crisis has provided an accurate representation of the impact of systemic shocks to non-resilient and unequal economies and societies, leading investors to give much greater importance to the social pillar in their investment approach. As a matter of fact, the crisis has brought about significant opportunities for investors in terms of the “S” within ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance). Our research shows that in North American equity markets the social pillar, which had been lagging behind the environmental and governance pillars in previous years, outperformed the other two pillars in the first quarter of 2020, in the midst of the market downturn.5

The factors that might have led to greater resilience of companies’ performance during the Covid-led market downturn are varied. However, companies that showed a strong response in terms of the protection of employees and of supply chain operations experienced smaller-than-average subsequent declines in stock prices.6

Other factors leading to outperformance, worthy of being cited, include strong pre- 2020 finances, a higher level of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities7 and low international exposure (especially to China, initially).8

The following sections will consider the extent to which social risks have become material for companies, and therefore investors, and how the latter can take action to mitigate such risks.

Social risks: a category deserving greater consideration

As outlined above, the Covid-19 pandemic completely shifted the discussion on social risks for companies and investors. While the general agreement on the materiality of climate change has built up over the years based on scientific evidence and growing interest from market participants, its social counterpart had a more abrupt evolution. Indeed, it is not surprising that it took a “black swan” event, such as this pandemic, to bring social issues to the center: the “S” does not follow a linear trajectory, the risks related to it are always there but they only manifest themselves violently when unexpected shocks happen.

In previous Amundi papers covering the social theme9, we highlighted how risks (and, on the positive side, opportunities) relating to the “S” pillar of ESG will be a key focus for years to come. While the last decade shaped “investing for the low-carbon transition” as we know it today (and the best is yet to come with COP26 in Glasgow this year10), we can expect that in the next one, at least, social risks will be incorporated into investment decisions on top of environmental-related risks. In fact, the concept of a “just transition” has increasingly been recognised by investors as a way to develop a more comprehensive and adapted response to climate change. It consists of taking into account the multiple impacts on workers, consumers and local communities, of the transition to low-carbon economies in investment frameworks.

Concretely, we consider social risks as being all risks emanating from social factors that can have a material impact on a company and its stakeholders. In this context, we have expanded the concept of “Double Materiality”, which the European Commission has developed for its “Guidelines on reporting climate-related information”, to include its social counterpart.11 We thus consider not only how social factors affect a company’s value (“first materiality”) but also how the company itself alters (positively or negatively) the social “status quo” of its stakeholders (“second materiality”).12 Indeed, as we will see further, the latter can also have major effects on a company’s value as stakeholder voices and expectations are increasingly able to shape market valuations and to raise issues to the level of materiality.

A notable example of how double materiality works is the probe around the OxyContin opioid painkillers produced by Purdue Pharma. The company, by enabling the supply of drugs without legitimate medical purpose, greatly contributed to US life expectancy dipping in 2015 for the first time in decades (second materiality).13 This complete lack of product responsibility has led to a US$8.3 billion settlement with the Department of Justice and several cases which are still being brought about (first materiality).14

It needs to be underlined that, naturally, social risks affect issuers across sectors and regions in different ways, as with climate change-related risks. However, maybe slightly counterintuitively, their impact can be even wider and more pervasive here than for their climate counterpart. Indeed, Moody’s estimated that over $8 trillion of the debt it rates is highly subject to social risks, versus around $2 trillion that faces environmental risks. At the end of 2019, Moody’s assessed that emerging market sovereign and sub-sovereign issuers, issuers from healthcare and education-related sectors, heavy industries’ companies (e.g. automotive, utilities) and consumer-oriented sectors with harmful effects for the society (e.g. tobacco, gaming) are most at risk from social considerations.15 However, the pandemic has accelerated this trend by highlighting social issues in most economic sectors and geographical regions and it brought the public scrutiny’s focus temporarily away from the “high-emitters” and from the traditional “bad guys” in terms of social practices.16

At a macroeconomic level of analysis, it is generally recognised that high levels of social inequality can have a negative impact on economic growth18, for instance through a decrease in investment flows.19 On top of being an obstacle to growth, income inequality leads to socioeconomic imbalances and episodes of social unrest that end up negatively affecting financial markets.20 Finally, there seems to be a vicious circle between income inequality and financial instability: higher levels of inequality lead to greater macro-financial risks that can then induce greater inequality.21

At a microeconomic level of analysis, in line with the concept of “double materiality” previously mentioned, we will frame material social risks through a stakeholder-based approach. It needs to be underlined that there is no clear consensus among asset owners and managers about which social risks are relevant and can indeed be considered material, thus we have attempted to highlight the ones proven to have materiality in their contexts.

|

Box 1 – Spotlight on the Taxonomy The EU Taxonomy, in its essence, is a science-based classification system, which establishes a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities that contribute to some or all of the EU’s six main environmental objectives.17 The social aspect is already integrated in the current Taxonomy via the inclusion of the minimum "safeguards" (based on OECD Guidelines and United Nations Principles), but it is not yet completely clear what this requirement will entail. Thus, the proponents believe a dedicated Social Taxonomy would help to rally investment in the just transition mentioned above and, more generally, in activities deemed beneficial for society. What is certain is that the European Commission working on social issues will increase the discussion around them and could have some major impact on the regulatory front, as has been the case for the green part of the Taxonomy. |

1. Employees

Labour and capital are nowadays considered the most important factors on which economic activity is based. In this context, the share of national income that is distributed to labour has been falling tremendously in the past two decades, especially in countries such as the US and the UK.22

However, the importance of the labour factor is not doubted and companies need to provide the required incentives to their employees if they want them to be motivated and to contribute to the company’s financial success.

The decision for a company on whether to invest in employees’ motivation and wellbeing is an important one as these resources could be otherwise directed to other more “productive” expenses.

However, numerous studies have proven that employees’ satisfaction is indeed correlated with better stock market performance for a company.

For example, employee satisfaction (assessed through the proxy of online reviews) was found to have a significant positive correlation with long-term stock returns across US companies.23 The same was observed when analysing employee satisfaction through the renowned and publicly available “The Best Companies to work for in America” ranking.24

Employees in all sectors and regions were deeply impacted by the pandemic with, naturally, major differences between “frontline” employees providing essential services and other employees that could continue their working life from their homes. In line with research underlining the stronger resilience of companies with better sustainability performance in the outbreak of the pandemic, studies have proven that companies that were already giving importance to employees’ working conditions prior to the crisis better withstood the market downturns.25 The link between employees’ satisfaction and firms’ performance is also expected to strengthen in the aftermath of the crisis.

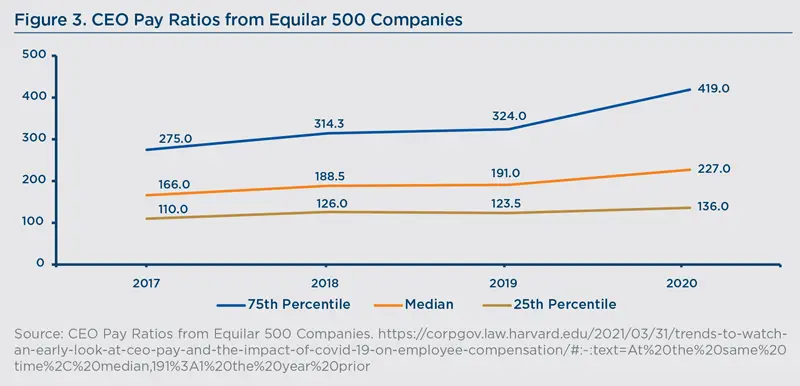

Regarding employees’ motivation and satisfaction, there is the “thorny” topic of the equity pay ratio, also called CEO pay ratio. Indeed, as mentioned above, labour in its entirety (and not only the C-level executives) is one of the key factors of production: all workers at all levels, naturally in different manners and to different extents, contribute to driving up a company’s value. In a number of jurisdictions around the world (notably the UK and the US26), it is now compulsory for public companies to disclose the ratio of CEO to median worker pay. The topic is more or less controversial depending on the regions and sectors; however, the public audience, as well as some corporate leaders and institutional investors, have shared their concern that an excessive within-firm pay dispersion is contributing to a rise in inequality.27 28

Nonetheless, the market seems to have a very clear idea about high CEO pay ratios: it does not like it. In an analysis focused on the US, markets had a significant reaction to the disclosure of these figures, thus showing the ratio is considered a relevant indicator when assessing a company in its entirety. Most importantly, companies reporting higher pay ratios experienced a significantly large negative reaction.29

In a broader context, when companies disclosed high CEO pay ratios and even after attempting to spin or edulcorate the news, the reaction from stakeholders has been negative: negative media coverage, less shareholder voting support for say-on-pay (SOP) resolutions and, relevant to the above, worse employee productivity and morale in the long run.30

|

Box 2 – Respecting Human Rights

Asset owners and managers should ensure the respect of human rights across their operations and their investments: it is their responsibility and it makes sense from a risk management perspective. They should adopt policy commitments to respect internationally recognised human rights, have a proper due diligence process in place in terms of identification, prevention and monitoring of human rights outcomes and should enable, to some extent, access to remedies for people whose human rights have been affected through the investments.33 As an example, Norges Bank Investment Management, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, clearly states what it expects from companies in terms of respect for human rights34 and takes active decisions to divest from companies posing an “unacceptable risk for violation of human rights”.35 |

To conclude, even if, in general, an excessively high CEO pay ratio is perceived negatively by the market and can have severe repercussions on companies’ profitability, it is even more of a problem when the median worker does not earn a living wage. Notably, US companies offering minimum wage contracts – insufficient to make a living – are now experiencing labour shortage issues due to the supply of unemployment benefits.31

This leads to the consideration that social cohesion, in the form of employees’ wellbeing, protection and fair pay compared to C-level executives, can be a key driver of financial performance and it is still underpriced by the market.

2. Consumers

Consumers are the second stakeholder to be taken into consideration. Their power on the future profitability of a company is immense, as they are capable (more or less depending on the sector and its switching costs) of deciding whether they will continue to buy from that specific company or if they will turn to a direct competitor. Consumer behaviours are shifting; consumers increasingly require the businesses from whom they buy products and services to avoid exacerbating social issues or, even better, to have a positive impact on them. Importantly, they expect these same businesses to start disclosing their social (and environmental) impacts across their whole value chain.

Several studies, implementing different research techniques, have proven over the years that consumers are more likely to choose products that they perceive as being socially responsible.36 In the longer term, this reflects in positive pro-company behaviours, such as purchase, loyalty and advocacy, given a company’s CSR activities match its consumers’ moral beliefs.37 Notably, this link between social responsibility and consumer satisfaction and loyalty was found to be significant across multiple sectors, from retail to banking.38

In this context, an example of a company that has behaved in line with the morals and values of its customer base is Nike, having chosen Colin Kaepernick, an ex-National Football League (NFL) player, as the protagonist of one of its advertisements. Kaepernick’s controversial kneeling during the US anthem before NFL games, a sign of protest against police brutality, likely cost him his NFL career. In the immediate aftermath of the ad, Nike stock prices reached an all-time high and its direct digital sales, benefitting from the ad, rose 36% over the quarter.39

Overall, a satisfied and loyal customer base can lead to excess returns that, in turn, do not experience enhanced volatility.40

In summary, for socially responsible companies, there is a higher likelihood that consumers will adopt pro-company behaviours (purchase, loyalty, advocacy), leading to higher profitability and excess returns.

3. Communities and Society

Importance must be given also to communities and the broader society that the firm can affect, directly or indirectly.

For example, it was observed that public mining companies investing in the relationship with the communities involved in their activities in order to avoid conflict had higher financial valuations in comparison to their peers, everything else being equal.41 An example «from real life» involves the social scrutiny around the use of fresh water and the impact of mine tailings in Chile: continuous protests from local communities led to a stoppage of copper shipments from a large mine and to more stringent requirements when starting a mining project, increasing costs for the mining companies.

We can naturally expect this type of communities-based social risk, which can also be known as “social license to operate”, to be more material for sectors such as mining and utilities whose operations can lead to major changes in the daily life of local communities. However, for sectors that are generally not particularly controversial, the need for a social license to operate can also be a material social risk. For example, in the beverage sector, characterised by the intensive use of water in its operations, Coca- Cola’s bottling plant operations in India were deeply impacted and, in some cases, entirely halted by conflicts with local communities due to scarce water resources.42

Overall, companies that have invested resources in building positive relationships with the communities impacted by their operations present a higher financial value than their peers, all else being equal, and ensure their operations are not heavily impacted by social unrest.

4. Regulatory Authorities

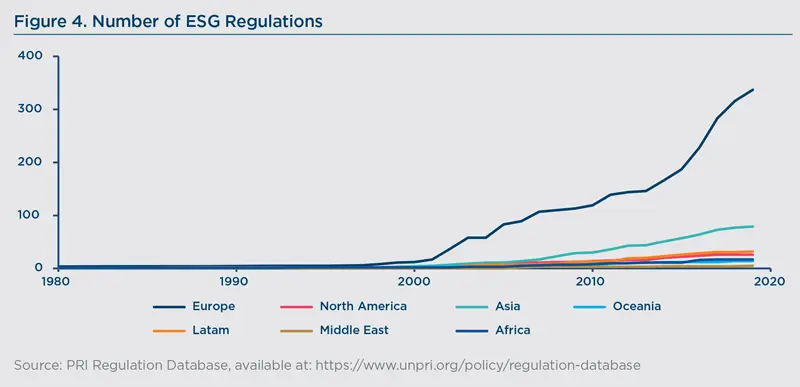

Moreover, regulatory bodies and governments are also powerful key stakeholders, able to profoundly impact a firm’s operations, business model and, finally, profitability. In the specific context of the Covid-19 crisis, governments – even those more on the liberal side – were forced to intervene in the economy and in the daily life of their citizens in a manner not experienced since World War II. While the extent of government interventions should naturally scale back when the situation stabilises, it is unlikely it will fully return to pre-Covid levels.

The scope of policies from governments and regulatory bodies relevant to corporations is varied: tax rates, labour laws (such as minimum wages policies), specific sector-based regulations (such as the sugar tax, etc.).

Firstly, in previous Amundi publications43 we have shared our perspective that the coming months could see an increase in corporate income tax rates, especially in developed markets. Indeed, US President Biden has been proposing to raise the rate from the current 21% to between 25% and 28%, depending on the final agreement. Furthermore, at the OECD and G20 levels, a global corporate tax rate is under discussion: for the moment, at the G7 finance ministers meeting on the 4th and 5th June, a 15% global minimum tax rate was agreed upon.44 Multi-national corporations have been, at times, heavily fined: for example, Google was forced to pay US$1 billion to the French government in order to settle a fiscal fraud probe.45 Also, some nations (such as Denmark, Scotland and France) have decided to make companies headquartered in tax havens ineligible for economic support during the crisis.46 For the reasons outlined above, we can expect companies headquartered in tax havens and/or implementing aggressive tax policies to be closely under the radar in the years to come.

Secondly, labour policies could be affected, with a particular focus on wages. Employment losses among low-wage employees have been much higher than for high-wage employees in countries such as Canada and the US. At the same time, employees earning a lower average wage were the ones suffering the most from the health and economic crisis: they were the “frontline” workers providing essential services and those employed in sectors that were shut down the most, such as the food service industry.47 Indeed, discussions about rises in national minimum wages have been happening across several jurisdictions: notably, with the proposed “Raise the Wage Act” of 2021, US legislators are trying to double the minimum wage to US$15 from the current US$7.25 for all workers across the country48. In this context, companies that have been paying their employees at wages lower than their industry peers and/or lower than the industry average will be more negatively affected: this is particularly true for sectors in which wages make up a significant part of the total costs, such as retail. For example, the largest US retailer, forced by US State laws to increase its starting minimum wage, suffered a heavier drop in earnings compared to peers paying their employees with industry-leading wages.49

Overall, a higher scrutiny and, consequently, stronger activity from regulators is expected, in terms of how companies consider and affect social issues within their operations. To give an example, the European Commission is currently working on a new directive that will require companies operating in the European Union (including non-EU-based) to apply a mandatory due diligence process regarding the respect of human rights across their whole value chain.50

To conclude, companies that have not taken upcoming social-focused regulations into consideration (such as corporate tax rates revision or minimum wage increases) have experienced worse financial results than their peers and it is expected they will continue to do so.

5. Investors

Lastly, investors are also a powerful stakeholder that companies need to account for. They provide firms with the needed capital to operate and achieve profitability, while being able to exercise a profound influence on decision-making. Thus, for businesses, having investors on their side, especially in uncertain situations and economic shocks, is of paramount importance.

Through the above framework, we have attempted to give a broad overview of some of the arising social risks investors should be taking into account as being financially material and thus potentially capable of influencing the short-term and, most importantly, the long-term returns from investments. Below, we provide ideas on how social risks can be integrated along the whole investment value chain.

|

Box 3 – Cross-Stakeholder Social Risks: Reputation and Litigation Litigation or liability risks can also be included in this category as they originate from the negative effect the company has on all stakeholders. There has been a remarkable rise in the number of ESG Litigations and, while in the past most were related to climate change, Covid-19 has increased the scrutiny on social issues.53 A notable case is the one of Bayer that, not having undertaken enough due diligence on Monsanto’s controversial Roundup weed-killer prior to the acquisition, will need to spend up to $10.9bn in its attempt to settle an avalanche of legal cases in the US.54

|

Incorporating social risks in the investment value chain

Investors should consider social risks in terms of the double materiality outlined above. Indeed, while on one hand their main concern is how social risks can affect a company’s value, on the other hand how a company exacerbates or mitigates social issues can, in turn, become a risk that can end up affecting its value as well, as shown in the previous section.

Investors should therefore consider incorporating social risks across the whole investment value chain: from the analysis of the social risk impact to the engagement and voting activities.

In terms of ESG analysis, asset owners can, supported by asset managers and advisors, identify the most material social factors influencing their portfolios. For example, at Amundi, ESG Analysis is performed based on 37 criteria (both generic and sector-specific), of which 19 are related to the social pillar. The generic criteria applied to all analysed sectors includes labour conditions and nondiscrimination, health & safety, client/supplier relations, product and societal responsibility (including tax practices) and local communities and human rights, mirroring the type of stakeholder-based framework proposed here.55

Importantly, the coverage of social-related data available on companies is increasing, thanks to growing disclosure requirements from governments and regulators. An example of this is the French Gender Equality Index launched in 2018, whereby publicly listed companies are required to make available their “Gender Score” evaluating their gender equality performance.56 Also, while quantifiable metrics on a company’s exposure to climate change risk are more easily available, the matter is a bit more complicated for social risks. As a result, artificial intelligence and, especially, sentiment analysis of natural language are increasingly used to support the analysis.57 The ESG analysis can then be translated into an overall ESG policy highlighting the values and objectives of the asset owner in terms of ESG factors and, in particular, in terms of social issues.

Investment solutions are also at investors’ disposal to help in the process of integrating social risks. A first possibility would be to apply a filter excluding issuers with poor social practices from the investment universe (with the help of the ESG social criteria mentioned above), thus increasing the level of protection from social risks. To go one step further, asset owners can decide to invest in strategies and instruments that directly aim to encourage issuers to modify their business models towards higher social inclusivity and impact. As an example, social bonds provide investors with the possibility to ring-fence their financing to socially beneficial projects and engage with the issuers on socially-related topics and indicators, while obtaining a risk-return profile in line with a vanilla bond of the same issuer, and extended impact reporting.58 Also sustainability-linked bonds with socially-focused KPIs are intriguing instruments: here, corporate issuers have a tangible monetary incentive to improve the social responsibility of their business models and practices. However, to this day, only two such instruments have been issued in the market.59

Within an ESG investment approach, ongoing engagement is also crucial. These dialogue activities are helpful insofar as asset owners can support companies to recognise their exposure and the impact (positive or negative) on their key stakeholders. They are also extremely influential in terms of “best practice” setting and for encouraging portfolio companies to develop and improve their social practices. Asset owners can also consider engagement in collective terms by joining key market initiatives focused on social themes, such as the Platform Living Wage Financials, which “encourages and monitors companies to address the nonpayment of living wage in global supply chains of the garment industry”.60 Lastly, but not least, as shareholders, voting at Annual General Meetings is a valuable opportunity to give clear guidance to companies regarding what is expected from them in terms of social responsibility.

To conclude, we expect social risks to become increasingly material and will continue exploring this topic in the months to come. In fact, the Covid-19 crisis opened Pandora’s Box of social risks and it is unlikely it will be closed again. On the bright side, firms with positive social practices are expected to provide attractive investment opportunities in the years to come.

Definitions & Abbreviations

1. Institut Montaigne (2019) “Poverty in the World: Where Do We Stand?”

2. UN World Social Report 2020 “Inequality in a rapidly changing world”

https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/01/World-Social-Report-2020-FullReport.pdf

3. https://www.oecd.org/social/inequality.htm

4. Vox EU (May 2020) “COVID-19 will raise inequality if past pandemics are a guide”

https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-will-raise-inequalityif-past-pandemics-are-guide

5. Amundi Insights Paper (June 2020) “The Coronavirus and ESG Investing, the emergence of the Social pillar” https://research-center.amundi.com/article/coronavirus-and-esg-investing-emergence-social-pillar

6. https://www.statestreet.com/content/dam/statestreet/documents/ss_associates/Corporate%20Resiliance%

20During%20Covid19_3046656.1.1.GBL..pdf

7. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X21000957

8. https://academic.oup.com/rcfs/article/9/3/622/5868420?login=true

9. https://research-center.amundi.com/article/social-bonds-financing-recovery-and-long-term-inclusive-growth;

https://research-center.amundi.com/article/day-after-4-inequality-context-covid-19-crisis

10. https://research-center.amundi.com/article/shifts-narratives-3-make-it-or-break-it-moment-why-investors-should-care-about-cop26

11. https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/policy/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en.pdf

12. https://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/policy/190618-climate-related-information-reporting-guidelines_en.pdf

13. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/01/30/801016600/life-expectancy-rose-slightly-in-2018-as-drug-overdose-deaths-fell?t=1623089716621

14. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54636002

15. “Heat map: Social considerations pose high credit risk for 14 sectors, $8 trillion debt” (Moody’s Investors Services, 31 October 2019)

16. https://www.cfauk.org/pi-listing/asset-management-after-covid-19-irreversible-change-or-back-to-where-we-left-off#gsc.tab=0

17. Climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, the transition

to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

18. https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/trends-in-income-inequality-and-its-impact-on-economic-growth-SEM-WP163.pdf

19. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/4553018/alesina_incomedistribution.pdf

20. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/03/19/Pricing-Protest-The-Response-of-Financial-Markets-to-Social-Unrest-50146

21. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2020/01/16/Finance-and-Inequality-45129

22. https://research-center.amundi.com/article/day-after-12-changing-shares-labour-and-capital-incomes-what-implications-investors

23. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165176517304433

24. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X11000869

25. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3560919

26. https://www.sec.gov/news/pressrelease/2015-160.html

27. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/134/1/1/5144785

28. The Equilar 500 tracks the 500 largest companies trading on one of the major U.S. stock exchanges (NYSE, NYSE American or Nasdaq) by revenue. More info can be found at: https://www.equilar.com/equilar500.html

29. https://www.sauder.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/2020-02/Equity%20Market%20Reaction%20to%

20Pay%20Dispersion.pdf

30. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3481540

31. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/26/smead-labor-shortage-wage-rises-a-democratization-of-us-workforce.html

32. Available at: https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=11953

33. https://www.unpri.org/human-rights-and-labour-standards/why-and-how-investors-should-act-on-human-rights/6636.article

34. https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/responsible-investment/principles/expectations-to-companies/human-rights/

35. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-norway-swf-ethics-idUSKBN25R1AW

36. https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezp.essec.fr/science/article/pii/S2352250X15003218

37. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0148296318303667?casa_token=OUVYVXZ0J_

EAAAAA:xbQMr2UdvwDrTY5_d5AN_CHvT-OvNOW-Vylz18TzBEXSwClmfnHBrI-Kp1g60KQ1PJNfunMZ4-U#bb0240

38. See, for example:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330571588_The_effects_of_corporate_social_responsibility_on_consumer_

loyalty_through_consumer_perceived_value; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326863804_Linking_customer_satisfaction_with_

financial_performance_an_empirical_study_of_Scandinavian_banks

39. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jiawertz/2018/09/30/taking-risks-can-benefit-your-brand-nikes-kaepernick-campaign-is-a-perfect-example/?sh=4ca8c82845aa

40. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228233854_Customer_Satisfaction_and_Stock_

Prices_High_Returns_Low_Risk

41. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264376641_Spinning_Gold_The_Financial_Returns_to_

Stakeholder_Engagement

42. https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=6529

43. https://research-center.amundi.com/article/day-after-4-inequality-context-covid-19-crisis

44. https://www.ft.com/content/95dd0c00-7081-4890-bcef-b9642312db4d

45. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-tech-google-tax-idUSKCN1VX1SM

46. https://www.taxjustice.net/press/scotland-joins-wave-of-countries-blocking-tax-haven-tied-corporations-from-receiving-covid-19-bailoutstax-justice-network-responds/

47. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---cabinet/documents/publication/wcms_756331.pdf

48. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/biden-raises-minimum-wage-federal-contractors-15hr-2021-04-27/

49. https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=6529

50. https://www.ropesgray.com/en/newsroom/alerts/2020/05/EU-Mandatory-Human-Rights-Due-Diligence-Legislation-to-be-Proposed-in-Early-2021

51. https://www.aon.com/getmedia/8d5ad510-1ae5-4d2b-a3d0-e241181da882/2019-Aon-Global-Risk-Management-Survey-Report.aspx

52. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228388417_Celebrity_Endorsements_Firm_Value_and_Reputation_

Risk_Evidence_from_the_Tiger_Woods_Scandal

53. https://www.lw.com/thoughtLeadership/ESG-litigation-roadmap

54. https://www.ft.com/content/f0e08509-f012-4190-a5a3-feab2cd77072

55. https://www.amundi.com/institutional/responsible-investment-policies-reports

56. https://travail-emploi.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/indexegalitefemmeshommes-ve-03-pageapage.pdf

57. For more information, refer to:

https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-atifc/publications/publications_report_aisolutions

58. For more information, refer to:

https://research-center.amundi.com/article/social-bonds-financing-recovery-and-long-term-inclusivegrowth

59. Sustainability Linked Bonds issued by Schneider Electric and by Novartis.

60. https://www.livingwage.nl/