Summary

Central banks remain credible regarding inflation

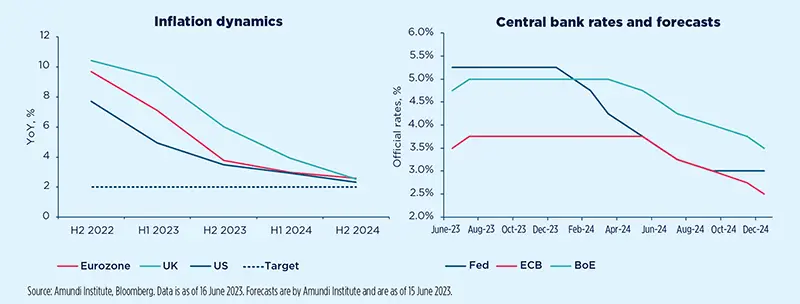

Central banks face a dilemma. Substantial monetary tightening has reduced headline inflation, but core measures are proving sticky, both in Europe and the United States. Even though inflation is still well above central bank targets, markets expect policy rates to be near their peaks. As central banks retain credibility, most measures of inflation expectations remain anchored.

The risks of inflation reaccelerating appear limited, especially as we expect central banks to maintain a restrictive monetary stance for an extended period. Past experience with advanced economies indicates that wage-price spirals do not materialise when monetary policy remains focused on meeting the inflation target. We also expect wage growth to moderate as growth slows and labour market pressures gradually ease, as currently underway in the United States. In the Eurozone – where wage growth picked up later than in the United States and with significant dispersion across countries – it may take longer for wages to moderate, but here, too, the weakening economic environment should contain any significant rise in real wages. Our reading of market-based expectations is consistent with this.

Consumer and business expectations have been more volatile, with consumer inflation expectations ticking up recently. After aggressively repricing their short-term expectations higher last year, business expectations have retraced progressively lower, although remain above their pre-Covid average levels.

Evidence from past episodes of high inflation in the United States suggests it takes about two years to bring core inflation down by half from its peak level. Our forecasts for the current episode are consistent with this. In Europe, favourable energy base effects and lower food prices will reduce headline inflation faster than core inflation. The impending economic slowdown will reduce the pricing power of corporates and, together with the normalisation of supply chains, help both core and headline measures to converge by the end of 2024.

Macro fragilities

Market vulnerabilities

| A world flooded by debt |

|---|

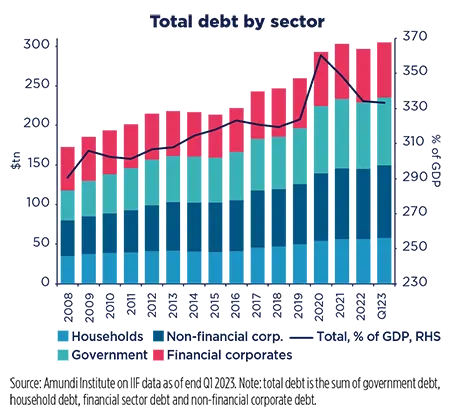

Global debt hit a record of $300tn in Q1 2023, or 333% of GDP. High debt could limit fiscal support in the case of a strong economic downturn, making the economic outlook more fragile.

| Tighter lending standards |

|---|

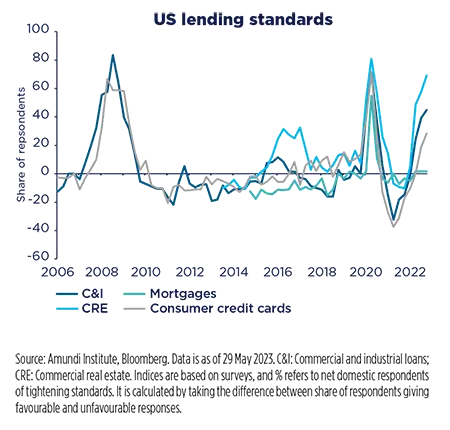

Lending conditions are tight, as borrowing costs for corporates and households have risen a lot, increasing the risk of an economic downturn.

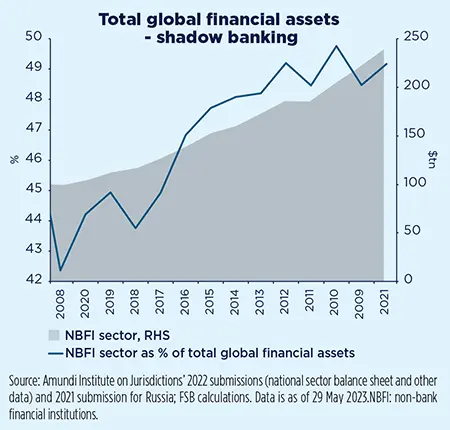

| The rise of shadow banking |

|---|

A significant risk to watch out for is the rise of shadow banking, which could threaten the financial system’s stability as the former is less regulated and can represent a hidden risk.

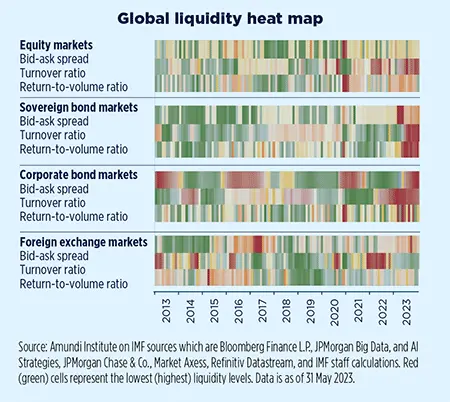

| Deteriorating liquidity in some market segments |

|---|

Given the rapid pace of monetary tightening, some key financial markets are suffering a clear deterioration of liquidity conditions.

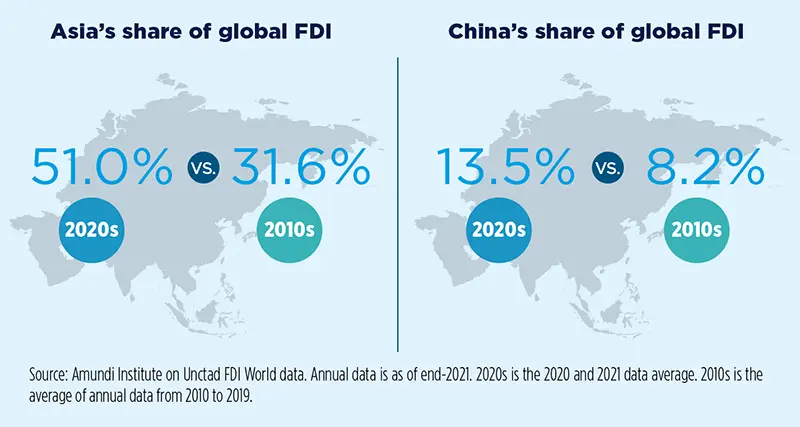

Asia to attract foreign flows

In the long term, we expect a structural, steady, and controlled downward evolution of the China-US relationship, rising regional integration, and China and India moving towards more sustainable growth models to make Asia an attractive region for foreign investors.

Despite intensifying geopolitical tensions, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in China and Asia have been rising steadily in recent years, continuing a trend that started over two decades ago. As of 2021, Asia hit 43.6% of global FDI, with China alone accounting for 11.4% of global FDI. The region is attractive to foreign investors due to its market size, labour costs and business environment, supported by effective government policies such as tax incentives, streamlined business regulations and infrastructure development. While the trend is based broadly across the region, with India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia attracting significant amounts of FDI, China remains the largest recipient of FDI in Asia.

In the long term, the rising role of digital technologies and the increasing integration of regional economies through initiatives such as the Belt and Road scheme – which is increasingly focused on China’s neighbours, both South and West – and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) should support the FDI trend. However, the region remains mixed in terms of economic development, regulatory frameworks and infrastructure, making the journey towards deeper economic integration challenging.

In the short term, early Q2 signals out of China, stemming from uncertain consumer confidence and the housing market, have raised concerns about its growth trajectory ahead. Our growth outlook (GDP growth is forecast at 5.7% in 2023) includes some modest recovery and is subject to the evolution of home sales in smaller cities, construction demand, youth unemployment and consumption. At this point, the authorities are unlikely to respond with a sizeable fiscal stimulus. However, the PBoC has definitely shifted to a more accommodative stance vis à vis its policy rates. The economy should remain on a moderate growth trend and – only in a worst-case scenario – 2023 real GDP could print at the 5.0% growth target. Yet, we should look at this short-term pattern as part of needed structural changes to engineer a more sustainable growth model.

India’s growth should also moderate in the short term, at around potential for FY2024 (5.5% YoY), after extremely robust post-pandemic growth rates while, longer term, the country’s growth model should become more sustainable thanks to renewed investment focused on newer sectors, such as semiconductors, electric vehicles and renewable energy.

US-China relations and Russia-Ukraine war to dominate H2

China has ended its strategy of ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ to emerge as a more assertive geopolitical player.

In H2, the geopolitical outlook should be dominated by US-China tensions and the Russia-Ukraine war. The current geopolitical realignment will evolve with third countries emerging as more important players. Looming risks include the threat of a surprise Israeli attack on Iranian nuclear infrastructure and the upcoming Taiwan election in January. On the Russia-Ukraine war, focus will turn to Ukraine’s counter-offensive, which will play out over the summer and into early autumn. Depending on battlefield developments and ongoing talks, a window for negotiations could open in the autumn. On US-China tensions, something has changed meaningfully. China has ended its strategy of ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ to enter the world stage as a more assertive player. This shift, coupled with US political dynamics, means that US-China relations should remain on a downward trajectory for the next several years. The steady and controlled decline does not exclude temporary improvements in the relationship. Indeed, the remainder of 2023 is likely to be relatively calm as there will be various high-level meetings between the two sides. While the United States will step up pressure on G7 countries to align with its policy towards China, many parts of the ‘Global South’ should remain non-aligned, leveraging their position to extract benefits from the US, EU, China and Russia simultaneously. On the upside, H2 2023 is likely to see further improvement in EU-UK relations, as well as progress in economic diversification with a Mercosur trade deal between the EU and parts of Latin America making inroads. Other events to watch are Spain’s election in July and the EU Parliament election in May 2024, which should drive the reform agenda moving forward.

Fiscal policy will weigh on GDP growth in the EU

EU countries face a new dilemma: how to increase green investments while respecting the new rules.

The EU Commission presented its legislative proposals. The goal of the new fiscal governance is to strengthen public debt sustainability and promote sustainable and inclusive growth through reforms and investments. The reference values of 3% of GDP (deficit) and 60% of GDP (debt) are unchanged, but the new governance takes into account the fact that Member States (MS) face different fiscal challenges (no one size does not fit all). Moreover, the rules are simplified: the only operational indicator for the budgetary adjustment path will be the volume of expenditure over several years.

The Commission made important concessions to Germany: a minimum fiscal adjustment of 0.5% of GDP per year will have to be implemented as long as the deficit exceeds 3% of GDP and green investments will not be treated separately.

In the short term, the withdrawal of the support measures introduced in 2022 will weigh on growth. Going forward, it is difficult to gauge the impact of this new discipline on fiscal tightening. The dilemma is: either MS will prioritise investment – and current spending will be cut – or taxes will be raised, which would be unpopular. Or they will sacrifice green investments to fiscal discipline, which would be counterproductive.

Time is running out with the European elections taking place in May 2024. These key technical points are still under discussion. An agreement by the EU Council is possible before the end of the year, but it is still far from being a done deal.