Summary

Macroeconomic focus

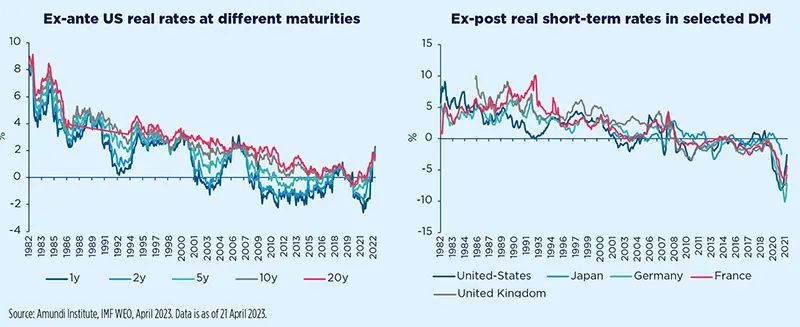

Will real bond yields come back down?

Demographic trends and weak productivity growth should continue to drive real interest rates.

Real, or inflation-adjusted, bond yields are higher than they were before the pandemic, but are likely to return to pre-Covid levels in the medium term, when inflation returns to major central banks’ 2% target.

Those who doubt policymakers will hit their inflation goals point to de-globalisation, structural changes in supply chains, higher public debt, and larger pay settlements. These are valid concerns, but won’t result in permanently higher inflation unless demand for goods and services were also to settle at higher levels. There is so far little evidence that this will be the case.

Meanwhile, those who question whether real yields will fall may point to the need for higher investment to manage the energy transition, potentially higher defence spending in a geopolitically fragmented world, and the costs of servicing very high public debt. Some also worry about a sustained rise in wages.

Workers’ pay poses the smallest problem. Wage rises have yet to match consumer price increases. There is little evidence that will change even though inflation has peaked, partly due to the continuing concentration and rising market power of large companies.

The impact of the energy transition will depend on how it is financed. For example, using higher carbon taxes to deter fossil fuel use would mean limit the impact on government balance sheets. Meanwhile, de-globalisation’s effects will be distributed unevenly, with large advanced economies relatively shielded. High public debt is more of an issue since major central banks have gradually begun to unwind their large holdings of government debt. Nevertheless, the main drivers of the decline in real interest rates – aging populations and declining productivity – are unlikely to reverse course in the foreseeable future. The inflation pressures and temporary stresses that economies are currently experiencing are therefore unlikely to prevent real bond yields from reverting to low levels.

Emerging markets

Short-term relief for emerging markets

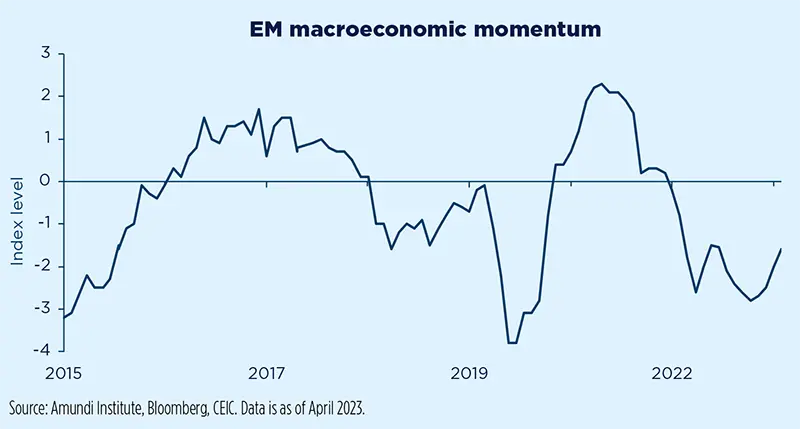

While the EM macroeconomic backdrop remains fragile amid slowing global demand and less accommodative financial conditions, EM macro momentum has been improving slightly, with the overall inflation deceleration proving sharper than expected – especially for the headline index – and growth perspectives being resilient.

As far as growth is concerned, we upgraded 2023 China’s GDP growth to 6.0% from 5.6%, as Q1 results proved better than expected, despite downgrading Q2 and Q3 sequential growth. While consumer spending has shown a modest recovery, housing sales have surprised to the upside and March export data exceeded expectations. However, this export trend appears unsustainable due to fragile global growth conditions. Other areas of vulnerability, such as the sluggish rebound in consumer confidence and lagging housing construction, corroborate a more subdued economic outlook going forward.

Signs of short-term relief are visible in less obvious countries, those with large exposure to the United States and, therefore, the expected US recession, such as Mexico. Even in this case, stronger-than-expected underlying momentum has prompted an upgrade to our 2023 GDP growth expectation to 1.8% YoY from 1.4%, alongside a marginal cut for 2024, to 0.2% YoY from 0.4%. Domestic demand remains strong, particularly household consumption which is supported by a very tight labour market – the unemployment rate is below 3% and wages are growing at 11% – as well as by strong remittances. Having said that, short-term catalysts need more structural measures (e.g., secure reliable energy supply) to take full advantage of the ongoing nearshoring and drive potential growth higher.

Generally, while a geo-economically fragmented world could provide low-hanging fruit to commodity exporters in the short term and to those countries that are better positioned on the value-added chain and are geopolitically aligned, most EM need to step up their reform process to tackle the challenges of a world that features lower growth in the medium-to-long term.

Macroeconomic snapshot

The rapid Fed tightening is starting to impact the US economy and we expect the economic landscape to deteriorate tangibly, driven by significantly weakening consumption and investment patterns. The credit crunch should weigh on growth and will define how deep the recession will be, while inflation is set to remain sticky, at least in the near term. The recession and below-par growth will help drive core inflation towards target over the forecasting horizon.

Notwithstanding our marginally upgraded growth forecasts – mainly due to the combined effects of betterthan-feared Q1 and carry-over effects – we expect very weak Eurozone activity, especially as financial conditions tighten and the weak US economic outlook worsens. Although China’s reopening represents a tailwind, it won’t be able to completely offset the deteriorating US outlook. Sticky core inflation will hold back consumption and keep the ECB in tightening mode.

With inflation remaining above target for several quarters, we keep seeing a cost-of-living-induced recession playing out in the UK. Although the outlook has improved on the back of incoming data and news flow, with lower energy prices removing downside risks, we still see the economy facing headwinds, which will also keep growth subdued in 2024. Energy remains a key risk for both the growth and inflation outlooks.

Although the outlook has improved on the back of incoming data and news flow – with lower energy prices removing downside risks – we still see the economy facing headwinds. In particular, we expect inflation to remain very high and above target, putting a lid on domestic demand. Growth will remain subdued in 2023-2024. Energy remains a key risk for both the growth and inflation outlook, together with food inflation and import prices.

In light of robust Q1 growth, we raised China’s 2023 GDP forecast to 6.0% from 5.6%. However, we acknowledge that 6.0% in 2023 pales in comparison to the striking 8.4% reopening expansion in 2021. There are areas of vulnerability, evidenced by the sluggish rebound in private sector confidence and the spike in youth unemployment. Coupled with subdued inflation, these factors offer policymakers a convenient justification to keep an accommodative stance.

The RBI stayed on hold in early April, leaving its policy rate at 6.5% against market expectations. The decision was not surprising, considering that the real policy rate hit a neutral(ish) level that was targeted at the beginning of the tightening cycle (May 2022) and the inflation rate has indeed moderated, as shown by the March report at 5.7% YoY, down from 6.4%, finally within the RBI target range. The 6.5% policy rate should be the peak of this tightening cycle.

The IMF was complimentary about Mexico’s sound fiscal, monetary and BoP situation at its recent meetings. Even growth, Mexico’s Achilles heel, has surprised on the upside supported by the very tight labour market. The country’s structural narrative is even more impressive thanks to nearshoring. Core inflation is finally slowing and Banxico might be done hiking too. However, the US slowdown will weigh on Mexico’s growth, where H2 2023 is likely to be weaker.

Brazil’s economy is slowing and Q4 2022 GDP even contracted, after a robust H1 2022, due to aggressive monetary tightening. Robust agricultural output likely lifted the headline above zero in Q1, but the softening labour market will outweigh these tailwinds driving 2023 GDP slightly below 1.0% (vs. 2.9% in 2022).

Inflation moderated to 4.7% YoY, but the BCB cannot cut just yet, as inflation expectations are de-anchored above target and Congress is yet to pass a new fiscal rule. Still, we see signs that the Selic rate will be cut over the summer months.

Central Bank Watch

DM CB still focused on inflation, some EM CB ready for rate cuts

Developed markets

The priority for central banks remains the fight against inflation.

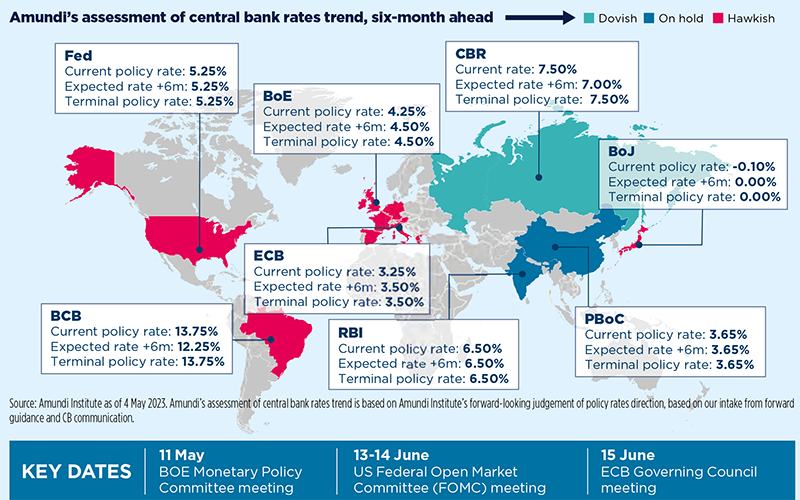

We think the bar is too high for the Fed to start cutting rates. The good news is that its policy appears to be working, according to its own metrics. There is evidence that inflationary pressure is slowing and labour market conditions are finally easing. The US economy continues to create jobs at a steady pace, but this job creation is only concentrated in a few sectors. However, it is hard to see a huge change in the environment for the Fed. This means another 25bp rate hike in May and little clear reason to cut rates in the short term. We think the market is not correctly pricing the trajectory of the Fed funds rate for 2023 and we expect the bulk of rate cuts to be delayed to 2024.

The ECB did not commit to future rate hikes, but Christine Lagarde was clear: “inflation is projected too high for too long.” The ECB is concerned about the strong diffusion of high energy prices to the rest of the economy. We confirm our expectations for the ECB terminal rate at 3.5%. The BoJ revised its forward guidance, no longer expecting policy rates to remain at low levels, while pointing to patience for policy continuation.

Emerging markets

March saw the bulk of the benign base effects kick in for EM headline inflation. This same effect should dissipate over the summer months. After that, inflation should stabilise or pick-up mildly by fall 2023. Specific factors such as the tight labour market and strong wage indexation or the gradual removal of price controls are offsetting or delaying a broader inflation decline across EM. Very few EM CB still have to complete their tightening cycle (e.g., Philippines), while most of them are pausing before turning to easing, even though inflation is clearly on its way down. Uruguay CB – this month’s exception – surprised with a 25bp cut to 11.25%, on the back of lower inflation and a looming recession. Even though they are being pushed back marginally, we maintain our expectation that a few CB will start their easing cycles as soon as Q3 2023, especially in LatAm (Brazil, Chile, Peru), followed by Eastern Europe and, tentatively, Asia. The easing cycle will gradually unwind very tight financial conditions and, accordingly, should alleviate the economic deceleration in several EM.

Geopolitics

Russia-Ukraine: lengthy war as likely as ceasefire negotiations

We maintain our view that a window for ceasefire negotiations may open in the latter part of this year.

The upcoming Ukrainian counter-offensive and recently leaked US intelligence do not change our expectations for the Russia-Ukraine war. Fighting will increase in the next few months. Ukraine may somewhat succeed at pushing back Russia, but will likely make no large territorial gains. Beyond the short-term horizon, we agree with the consensus view that the war could last for a long time. Indeed, Russia’s behaviour puts upside pressure on this scenario: Russia is increasing its diplomatic efforts to shore up international support and resources. It feels emboldened by China’s support; its economy has shifted into war mode and Russians have become used to the war. There is also the notion in Russia that it can ‘wait out’ Western support for Ukraine.

That said, we maintain our view that a window for ceasefire negotiations may open in the latter part of this year for various reasons. First, there are valid reasons for Ukraine to negotiate. It faces weapons and manpower shortages. The difficult economic conditions in the West, which are increasing dissatisfaction among the public, could weigh on political support for the war and Ukraine knows support will not last forever. Ukraine will be able to extract a lot of concessions from the EU and the United States for laying down arms. Second, there are valid reasons for Russia to negotiate. Minor territorial gains can be sold as victories. Russia has already expanded its sphere of influence. Putin is also likely to see any further economic weakening of Russia as being more detrimental to its longerterm strategic interests. Lastly, there has been ample peace-making activity of late, with European leaders travelling to China for talks.

Policy

US debt: the spectre of default resurfaces

The debt ceiling has been changed 102 times since WWII, so investors mostly ignore such episodes.

The debt ceiling was reached on 19 January. This limits the total authorised amount of federal debt. In theory, the Treasury can no longer issue debt. If it were to run out of liquidity, barring extraordinary measures, the United States would default. In practice, the Treasury prioritises payments and reduces spending (e.g. social security…). A grace period then follows. This year, it is estimated that the Treasury will run out of cash before the autumn, possibly in June.

It is estimated that other expenditure will have to be reduced by an average of 20- 35% per month to free up enough cash for interest payments during the summer, when tax revenues are generally less buoyant.

The experience of 2011 suggests that risking default is perilous. In August 2011, despite the debt ceiling being raised, S&P downgraded the Treasury’s debt, citing more uncertain governance. Credit spreads and the equity risk premium jumped immediately, as did implied equity volatility. The Treasury had to resort to extraordinary measures to meet its financial obligations.

In 2013, the Fed simulated the effects of a one-month impasse, during which the Treasury would nevertheless honour all interest payments. The result was an 80bp rise in the ten-year Treasury yield, a 30% fall in the stock market, and a 10% fall in the dollar.

A US default is highly unlikely, but a period of financial turbulence in the run-up to that fateful date cannot be ruled out.

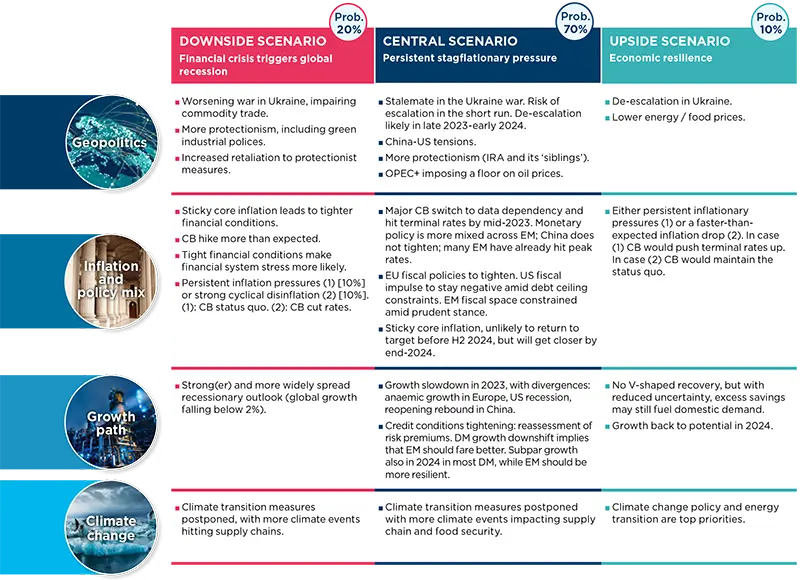

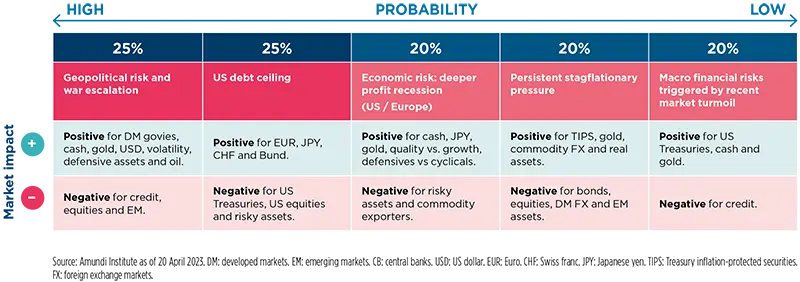

Scenarios and Risks

Central and alternative scenarios

Risks to central scenario

Amundi Institute Models

US Financial Conditions Index (FCI)

Financial conditions are a key determinant of the future state of economic activity.

What is the model about?

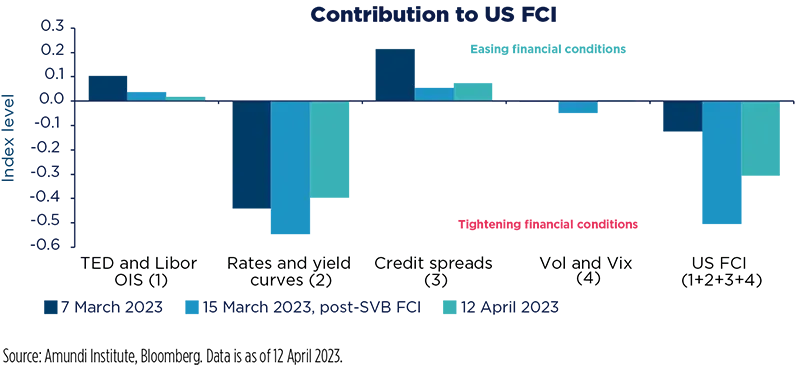

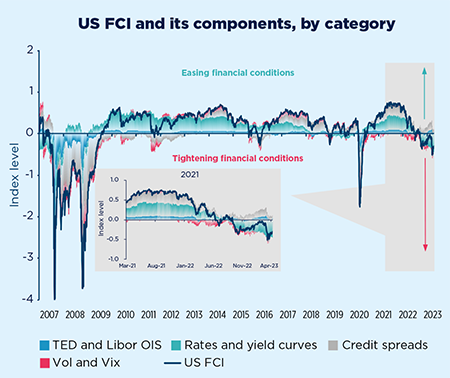

- The rationale: financial conditions are a synthetic measure of how easily firms, households and governments can finance themselves. They provide valuable information regarding future risks to liquidity provision – and thus economic activity -- arising from build-up imbalances in borrowing rates, credit spreads and market volatility. FCI is also actively used by monetary policymakers to study the broad effects of monetary policy on financial markets.

- Model setup: the FCI is set up by combining a comprehensive set of financial data: money market rates, sovereign bond yields and the slope of the yield curve across tenors, credit spreads and cross asset volatility. The goal is to capture the interactions between the financial system and the real economy, assessing whether monetary policy acts as a support to growth or as a headwind.

- Model output: the index is an equally-weighted aggregate of single components, normalised with an expanding method. A below-zero reading means that financial conditions are tightening, while deviations above zero mean they are easing. The former often translates into an economic slowdown, while the latter means that the likelihood for the real economy to be affected by financial stress is low.

What are the current signals?

- The current tight FCI stance is mainly due to: rising interest rates, bond market volatility and extreme yield curve inversion. Unlike recent periods of financial stress (2011, 2015, 2018), there has been little transmission from monetary policy to the credit channel: US credit is still contributing positively to the US FCI.

- The limited spillover to credit spreads makes the asset class the weakest spot if expectations of an imminent Fed pivot disappoint. In this case, the US FCI may tighten further, hit by credit and money markets.

Infographic - Markets in charts

Equities in charts

Developed markets

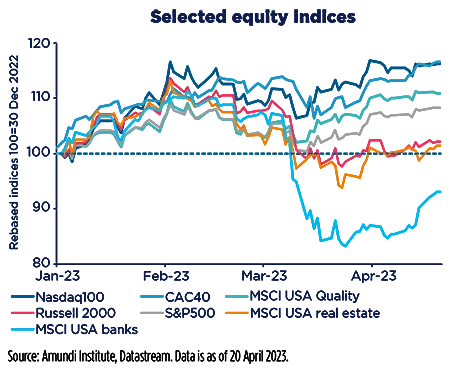

Equity is rebounding, but behaviour is uneven.

| Quality plays maintain the advantage |

|---|

Despite some banks rebounding, quality is maintaining its advantage, as well as the Nasdaq. The CAC40 index is competing with the Nasdaq.

| US market expensive again |

|---|

The strong resilience of the US equity market is rapidly making it expensive again. Other markets remain around historical averages.

Emerging markets

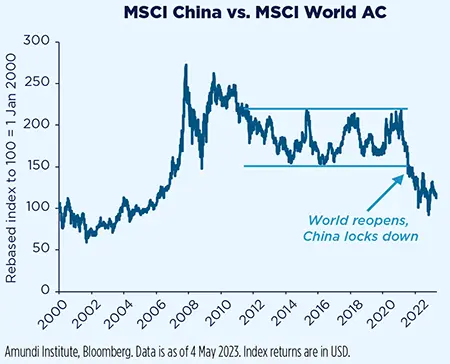

China’s earnings growth has started a recovery path thanks to the economic

reopening.

| Still room for Chinese equities |

|---|

After two years of China’s equity underperformance, the reopening of China’s economy is a huge catalyst for Chinese equities, supporting a positive view for the asset class.

| China earnings are set to rebound |

|---|

Some recovery is expected in China’s earnings, with its domestic economic recovery thanks to its reopening and the global cycle, which should accelerate in the second half of the year.

Bonds in charts

Developed markets

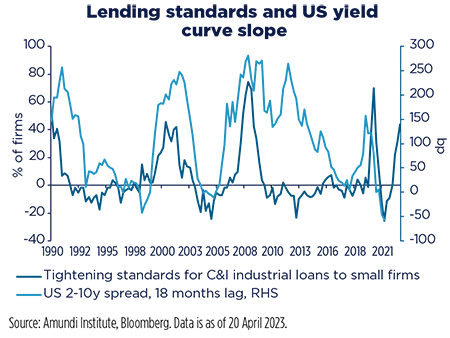

| The curve lags lending standards by 18 months |

|---|

The share of banks tightening lending standards to corporates leads by over a year both actual loan growth and the yield curve.

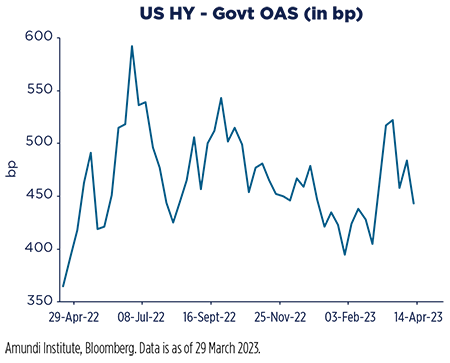

| HY spreads retraced most of March widening |

|---|

Emerging markets

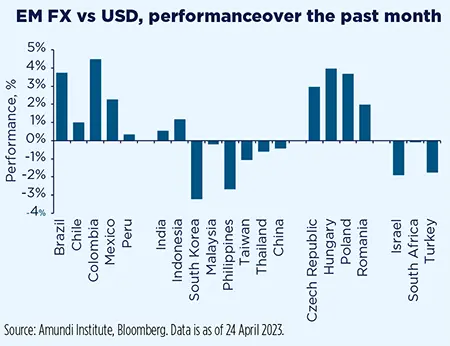

LatAm and CEE currencies have benefited from USD depreciation.

| EX FX recovering thanks to USD depreciation |

|---|

The EM FX that benefited the most from USD depreciation over the past month have been LatAm and CEE currencies.

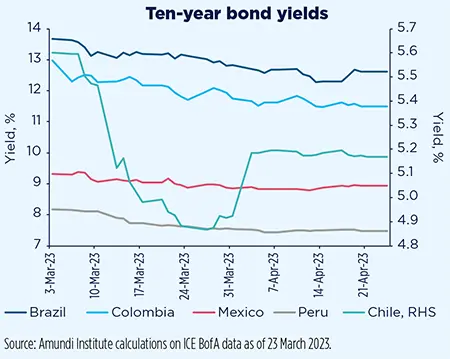

| LatAm local bond yields down on the month |

|---|

For local bond yields, the drop has been particularly evident in LatAm, the region that is most advanced in terms of the zightening cycle ending and inflation decelerating.

Commodities

Cartel back in power

An unusual alignment of planets for oil could help prices defy gravity.

An unusual planetary alignment made it possible for OPEC+ to preemptively cut output without risking losing market share or crashing demand. US producers on the sideline, chronic energy underinvestment, ample spare capacity and decoupling Chinese demand gave room for action. The US withdrawal from the Middle East is eroding Western leverage on oil and leading to greater interest alignment within the cartel. With tighter markets by autumn, we see prices converging towards a $90-95/barrel range by year-end, with less sensitivity to the economy and more resilience than other cyclical assets. A break above $100/barrel looks optimist: output cuts due to weak demand are less impactful and economic deceleration is at its beginning. In the short term, we see range trading amid richer valuations and weaker momentum.

Currencies

Rays of sunshine for EURUSD

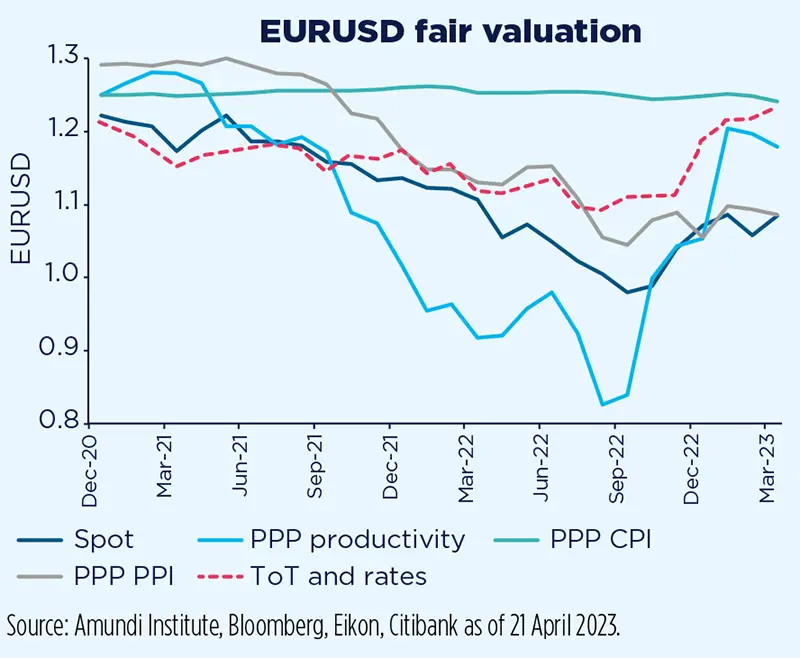

Recent EUR structural headwinds are improving fast.

US inflation and the Fed remain the key short-term risks, yet the asymmetry from here is less supportive for the USD. When looking for candidates to express this view (JPY and CHF work best in recession), the EUR screens nicely in this cycle. Its low-beta profile and improving domestic conditions suggest a higher exposure to the single currency. EUR fundamentals are improving fast (whether inflation (PPI), productivity (CPI/PPI), terms of trades (ToT) or rates differentials) and global portfolio flows have not reflected that yet. Eurozone investors remain net creditors to the rest of the world (it started once the ECB adopted the NIRP) and, despite the move in EUR rates, there has been no massive reallocation of capital so far. This is something we expect to drive EURUSD higher in the coming months.