Summary

Geopolitics: it’s now all about power and might, but core interests will hold

Key Takeaways

With multilateralism retreating, diversification is increasingly critical for investors.

In a multipolar world where leverage comes from critical resources and military power, governments are prioritising resilience. AI and defence spending should remain supported despite high levels of public debt. The USD will remain the reserve currency given the lack of alternatives, but its status is likely to weaken as a wider set of alternatives emerges, supporting gold.

New security alliances and trade deals are emerging despite intensifying economic friction as policymakers seek to compensate for the eroding global order. These will ensure global trade and investment continue to flow.

Following the US strike on Venezuela, growing threats against Greenland, and intensifying protests in Iran, we recap our expectations for geopolitics in 2026.

It has been our long-standing assumption that the level of geopolitical risk would continue to rise into 2026. Indeed, one of the drivers leading us to this conclusion is the melting ice in the Arctic. It is opening new shipping routes, intensifying resource competition, and creating shorter routes for Russia and China to reach North America. We have therefore always taken Trump’s Greenland aspirations seriously.

This year will be dominated by Washington seeking to expand its powers domestically and internationally. Tensions with Russia are more likely to intensify than abate, at least in the next several months. The Middle East will continue to see change. Tensions between China and the US will remain, but our base case is no escalation. The AI race will continue and shape the Great Power Competition and, with no regulatory oversight, the political and social consequences will likely be significant over time.

There is plenty of risk out there and avenues for things to go wrong. There are more active conflicts today than at any point since the end of World War II as countries seek to change geopolitical realities to their advantage. As economic friction is more likely to intensify, governments and investors will continue to diversify to build resilience. There will be winners and losers, or at least countries and regions better able to navigate the emerging new order. In short, 2026 is now all about power and might. However, overall, we expect core interests to hold and prevent wide-scale escalation.

Expect more interventionist US foreign policy

Early in Trump’s second presidency, we outlined a framework for how to think about US policy. Most of the policies pursued by this administration seek to achieve the following objectives: get a better deal for the US, achieve greater economic self-sufficiency, and increase Washington’s power. This framework still holds.

We anticipated that the Trump administration would oust Maduro with military means. But Trump’s readiness to leverage US military strength to achieve geopolitical goals is now ringing alarm bells for allies and adversaries alike.

Should the president be faced with a divided government after the midterm elections, which is likely, he will also likely double down on foreign policy. Limited ability to shape domestic politics usually encourages a president to do so.

The US under Donald Trump is, however, unlikely to undo the pillars that have cemented US power over the past few decades. There are US presidents and US interests, and while the former come and go, the latter usually stay. NATO and US alliances are essential US interests and eroding these will likely face resistance from within US power structures.

Similarly, a world divided into spheres of influence, where the US drops support for Ukraine and allows Russia to swallow it while China’s Taiwan ambitions are accepted by the US, would clash with core US interests and is therefore not our base case expectation.

Greater US interference in Latin America is now a given after decades of largely ignoring the continent. The US has already put Cuba on notice and warned Mexico and Colombia. Trump’s LatAm strategy can be summarised as reducing soft power via aid and ramping up economic and military pressure. This aims at weakening drug cartels, allegedly achieving a better deal for the US, and undermining regimes not aligned politically with the US. But Latin American politics is also moving towards the right because of domestic electoral shifts. Important elections are on the agenda in 2026, such as in Brazil, Peru, and Colombia.

However, Trump’s repeated emphasis on Venezuelan oil now being controlled by the US will cause memories of previous ‘US imperialism’ which was also responsible for the rise of far-left politics in the continent in the first place. Trump is therefore, ironically, a risk to his political allies in LatAm.

Significantly reducing China’s role in the region will be difficult as Beijing has heavily invested in infrastructure (such as ports and telecoms), resource exploration, and diplomacy in the subcontinent. For many countries, China is as important a partner as the US.

Europe faces a critical year

Forcing regime change in an adversary country, Venezuela, which can be considered geographically and strategically important to the US, is different from seizing territory from an allied country. While Greenland, due to its geography and sparse population, would be easy to seize militarily, the costs for the US are too high: military action against an ally would erode the NATO alliance and cause ruptures with other US allies, a key strength the US has vis-a-vis Russia and China.

The recent controversial National Security Strategy emphasised the importance of US alliances and Europe as an ally. Most US aspirations over Greenland can be achieved without a military takeover, the US has an agreement with Denmark to allow it to have military bases and extract natural resources; the Danish government has signalled readiness to improve the current terms.

Militarily seizing Greenland by claiming that Denmark has no right over it would open Pandora’s box and could lead to many challenges over territorial realities created since at least the 18th century. However, the issue is unlikely to go away — Trump will continue to press the matter to extract maximum concessions and seek to force a sale. But any action over Greenland is unlikely to be immediate at a time when tensions with Russia are building over the lack of an agreement on Ukraine.

Despite progress on aligning the Western position on how a ceasefire would be secured, we see the continuation of the Russia–Ukraine war as the most likely scenario, at least for the first several months of the year. The base case is an intensifying hybrid war, with potential sporadic flashpoints beyond Ukraine.

Europe will likely undergo greater political transformation this year as a result of defence spending and a fickle US forcing Europe to step up. A big focus will be on Germany’s ability to spend and the wider impact on the European economy. The upside risk would be a ceasefire potentially allowing Europe to capitalise on Ukraine’s reconstruction.

Hungary holds elections that could bring political change to the EU should Viktor Orbán be voted out of office, removing one stumbling block to more EU integration. Geopolitical pressures will likely continue to force EU leaders to push forward difficult reforms, but the pace will likely remain slow, also because the US seeks to erode EU unity. Even though elections are only scheduled to take place in 2027 in France, 2026 will likely see campaigning intensify.

China will continue to flex its muscles, but seek stability

China is likely concerned about the Trump administration’s renewed interest in Latin America and its desire to reduce Chinese influence in the region. However, both the US and China have realised their mutual dependencies in 2025. The US understands now it can’t do much without Chinese rare earths, while China’s economic performance and social contract (political control in exchange for economic prosperity) depend on global trade flowing. Therefore, in 2026 there is likely a limit to how much the relationship will deteriorate. Tactical deals between the two are possible, but a material change in the relationship is unlikely as trust remains low. We expect this ‘tense understanding’ scenario to persist even as Xi and Trump are expected to meet. Questions over Taiwan’s political status will continue to grow as geopolitical realities are changing and China expands its influence campaign and geopolitical power.

Prepare for more change in the Middle East

The Middle East will see ongoing political uncertainty. The Iranian regime is weakening, and the odds of regime change are rising through a combination of domestic protests and likely involvement from Israel and the US. 2026 could therefore be the year in which the country sees a leadership transition. The question is whether it will only be a change at the top or a more radical shift.

There are wider power shifts underway in the region. The Gulf is getting attention because of growing investments. But there is a power rivalry between the UAE and Saudi Arabia, a weakening Iranian grip, an unstable Syria, and Israel is facing elections. How this restructuring ends is currently hard to predict.

From Beijing to the Middle East, the global landscape is shifting. The US and China may still cut occasional tactical deals, but a true reset looks unlikely, while Iran’s regime is weakening and the odds of a significant political change are rising.

Key implications for 2026

|

Midterm election math: pain, policy progress, and Trump’s playbook

Measuring President Trump’s political capital ahead of the midterms

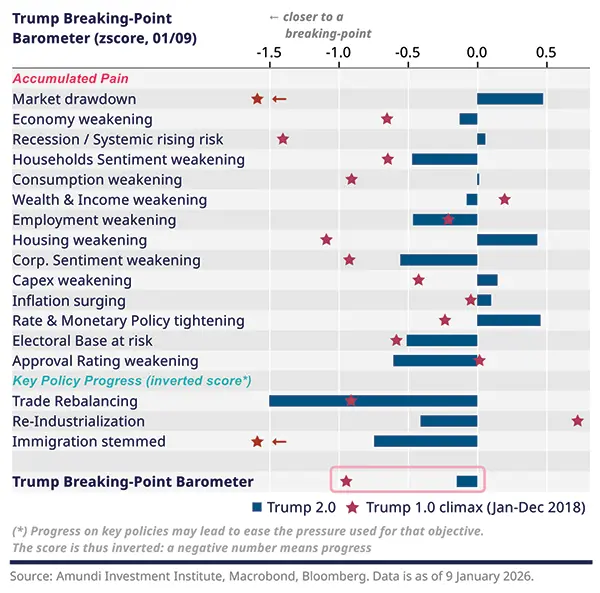

We assess the economic and political costs of President Trump’s policies to anticipate how difficult it may be for the Republican Party to retain its majority and whether future US policies are likely to be disruptive.

Our approach combines two dimensions:

Accumulated pain indicators: measuring accumulated economic and political pressure across a set of ‘pain’ indicators — pressure on markets, households, housing, corporate sector, the broad economy, recession risks, inflation, rates, the Fed, and the dollar, living conditions of Trump’s electoral base, and polls and approval ratings.

Key policy progress indicators: tracking progress on core administration priorities. As those objectives are met, the administration may be more willing to ease the pressures that motivated those priorities — trade rebalancing, re-industrialisation, partner concessions, middle-class recovery, and stemming immigration.

Market drawdown - leading signal for the broader economy

Household pain - particularly consumption, confidence, jobs, and income

Housing stress - key for households (affordability) and construction

Corporate pain - capex, manufacturing activity, and corporate confidence matter for jobs and re-industrialisation

Broad economic pain - amplified by higher perceived recession risks

Surging inflation - hurts households and undermines a key election pledge

Easing rates, Fed stance, and the dollar - reduces pain for households, firms, and exporters

Electoral base pressure - living standards of Republicans, the middle-class, and voters in swing states

Polls and approval ratings - midterms on the horizon

Trade rebalancing - lower imbalances, higher customs duties (to limit the deficit), stronger domestic consumption in China

Early signs of re-industrialisation - via reviving the economic fabric, investments from abroad, on/near/re-shoring

Partner concessions - EU: LNG buying, less tech pressure, military spending. China: voluntary export cuts, market access, rare earths

Middle class recovery - the natural Trump electorate: lower wealth inequality, job creation, wages

Stemming immigration - improving middle-class purchasing power and job prospects

Key finding: pain peaked, but pockets of weakness matter for the midterms

Pressure peaked in spring 2025. That peak appears to have prompted a tactical retreat by the administration, reflecting both political calculation and some measurable policy progress on trade and immigration.

Overall, aggregate pain is lower today than at that spring 2025 peak, but it remains meaningfully higher than at inauguration.

The main deterioration is concentrated in employment, consumer sentiment, and the living conditions of Trump’s electoral base — precisely the areas most likely to drive midterm turnout and swing voting.

Trump 1.0 offers a useful reference: disruption rose sharply into late‑2018 and then eased, with milder aftershocks thereafter. A similar pattern — intense pressure followed by a moderated, domestic‑focused phase — is plausible for Trump 2.0.

Pain peaked in spring 2025; the risk now sits in employment, sentiment, and the living conditions of the electoral base.

Our “Breaking‑Point” Barometer combines accumulated pain and policy progress. A lower reading indicates rising pressure alongside recorded policy gains. The red arrow in our chart highlights the end‑2017 to end‑2018 pressure spike and serves as a stylised comparison for current conditions.

Detailed component scores in the following table highlight that some indicators (employment, sentiment) are weaker now than during the early Trump 2.0 period, while progress on trade and immigration registers as material gains.

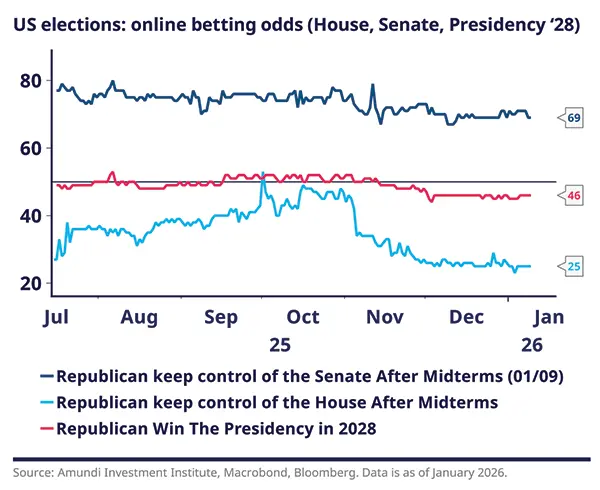

Lead midterm indicators suggest an uncertain outcome with risk of losing the House

Sub-factors in our Barometer

Three empirical lead indicators tend to shape the midterms outcome:

Presidential approval – especially among independents and swing voters. Current approval levels are weak, although the Republican base remains mobilised.

Economic health – most importantly employment, inflation, household income/wealth and housing affordability. These measures are broadly average, but localised weakness matters.

Local political dynamics – seats at stake, local political context, campaign dynamics, fundraising. These are presently mixed: seats on the ballot are not unusually challenging to win, but Democrats have regained momentum.

Taken together, the signals are mixed. Given the narrow majorities involved, the Republican Party is at significant risk of losing the House. Leading up to the midterm elections, we expect President Trump to favour fast, attributable, and domestically focused moves, similar to what his predecessors did.

Likely policies to be implemented to improve Trump’s standing at midterms

|

The midterm elections will have an influence beyond US borders

Trump’s foreign policy will be influenced by the midterms. The desire to limit economic volatility will likely lead Trump to maintain his fragile trade deal with China, even if episodic tensions continue.

Buoyed by the administration’s perceived military success in Venezuela, which has resonated with some voters, Trump is likely to pursue additional foreign‑policy wins in Latin America and beyond. Iran deserves close scrutiny in that context.

If Republicans lose the midterms, Trump will probably lean even more into foreign policy, given his reduced domestic leverage.

The administration will likely act sooner than later to deliver visible results before the election; a Republican midterm loss could see Trump lean further into foreign policy as domestic leverage diminishes.

Conclusion

Domestic policy and economic uncertainty have eased since their spring 2025 peak, but weaknesses remain in areas that will matter most in the midterms. The administration is therefore likely to deploy its playbook aggressively and sooner rather than later — targeted fiscal spending, purchasing-power and affordability measures, deregulation, selective diplomacy and an emphasis on quick, attributable wins.

Signals to watch include a shift in polls, the jobs picture, housing affordability, and voter swings in key districts.

History suggests Trump will likely lose the House majority — an outcome currently priced by online betting markets. Until then, he will probably try to enact as many of his planned reforms as possible before the election.

Post‑midterms, should the House be lost, policy would need to be more bipartisan, implying less disruptive domestic measures and a greater focus on foreign policy.