Summary

- What is happening to Credit Suisse: Credit Suisse’s share price plunged further this week and the cost of insuring the bank’s bonds against a default has reached distressed levels. The bank’s insurance costs have risen due to a crisis of confidence following the failure of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). After a frenetic day, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) announced it is prepared to support the bank’s liquidity. This was followed by a statement from Credit Suisse outlining that it will borrow up to 50 billion Swiss francs from SNB to strengthen its liquidity and buy back some of its senior debt.

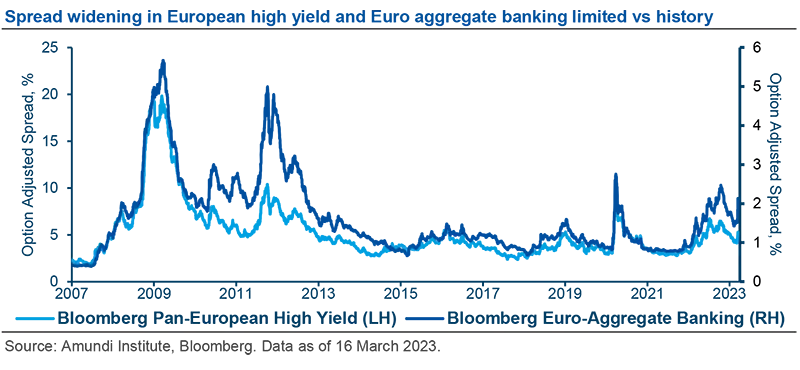

- The European banking sector is solid, with measures having been put in place after the great financial crisis to limit contagion risk. Over the last decade, regulations have been strengthened to ensure that the regulatory framework addresses any outstanding challenges to financial stability. Given that Credit Suisse is a Globally Systemically Important Bank1, regulators will closely watch developments and act to limit any contagion by the wider European banking sector. Despite recent market volatility, the banking sector is functioning well. The limited widening in the credit spreads of other major European banks in response to events at Credit Suisse suggest that the contagion effect is contained so far.

- Outlook for the European banking sector. In our view, the European bank sell-off is mainly driven by profit-taking and a reassessment of recessionary risks, which is not supportive for the profitability of the sector. In the case of a further escalation in this crisis, we expect the majority of the counterparty exposures to be collateralised, so we do not expect material losses from a potential resolution or wind down. The sector is well-capitalised and liquid and we don’t see any other specific instances that pose large risks to other banking stocks. It will be important to monitor liquidity and deposit flows for the sector over the coming periods.

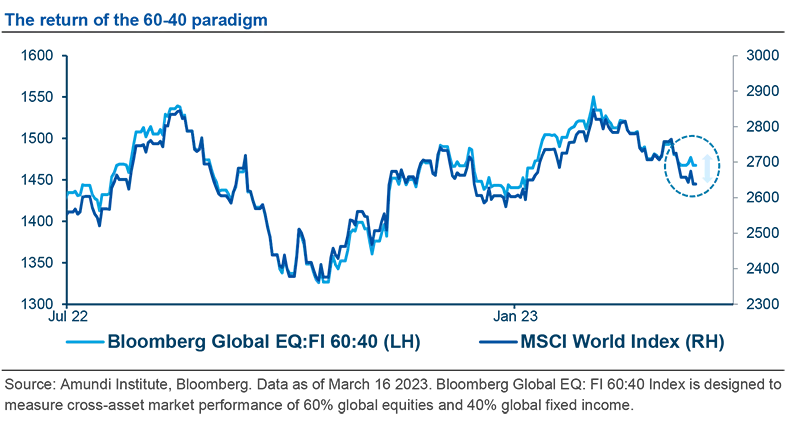

- Overall investment stance: We reiterate the need to keep a cautious stance on risk assets at this stage, as the vulnerabilities that have built up during the recent rapid interest rate hikes are starting to materialise. On a positive note, government bonds have demonstrated their role as a diversifier in this crisis, with the return of the 60-40 (60% equity – 40% bond) allocation paradigm.

What is happening to Credit Suisse?

The Credit Suisse turmoil appears to be driven by a crisis of confidence, with markets putting banks under scrutiny following the SVB failure.

The failure of SVB and other regional banks in the US, which led to the turbulence now affecting Credit Suisse, can largely be attributed to the sharp increase in rates and the inversion of the yield curve. When the yield curve inverts, “carry trades” (buying long-term securities and funding this with short-term securities) fail to work. SVB was exposed to this type of carry trade, and this was one of the catalysts that led to a run on its deposits and, ultimately, its failure.

The events at SVB triggered negative investor sentiment within the banking sector at a time of central bank tightening. Within Europe, Credit Suisse already stood out as an institution which had been experiencing deposit outflows for some time and hence was on investors’ radars.

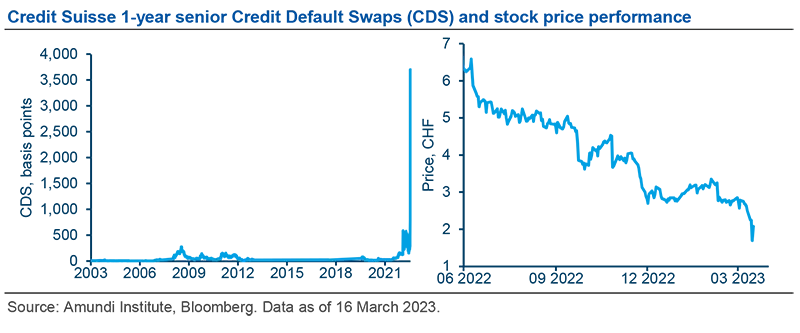

In recent days, Credit Suisse’s share price plunged further as the cost of insuring the bank’s bonds against a default on a one-year horizon (1-year senior Credit Default Swaps) reached distressed levels. Further accelerating the negative sentiment towards the Swiss bank was the announcement that its largest shareholder, the Saudi National Bank, was not open to making further liquidity injections into the bank. This added to the already fragile sentiment following the announcement earlier in the month that the bank had delayed the publication of its annual report to address comments from the US regulator.

The bank, Switzerland’s second-largest lender, has experienced several years of trouble that has led to senior management changes, legal problems and significant losses last year. The bank’s troubles have also led clients to withdraw billions of assets in just a few months and large investors to sell their stakes in the company. To address this complicated situation, the bank has engaged in a turnaround project which includes selling its investment bank unit. Despite this, however, uncertainty about its outlook remains high.

The Credit Suisse crisis is very different from the one at SVB, which ran into asset liability problems driven by rising interest rates. The Swiss bank is far less exposed to interest rate risk, according to the stress simulation required by the regulator. This is more of a crisis of confidence which is affecting the bank.

In the short term the intervention from the Swiss National Bank (SNB) should allow market sentiment to take a breath.

After a frenetic day, the SNB announced it stands ready to support the bank’s liquidity and this was followed by Credit Suisse outlining a plan to borrow up to 50 billion Swiss francs from SNB to strengthen its liquidity and to buy back some of its senior debt. This should allow market sentiment to take a breath. There is some value embedded in parts of the group, and throwing out the baby with the bathwater would be counterproductive for all market participants.

What is the outlook for the bank and what actions could be put in place by regulators to handle the situation?

Investors expect some changes to the bank’s new strategic plan, the selling of unprofitable businesses and a focus on its retail and wealth management ex-US business in particular.

Investors expect some changes to the bank’s new strategic plan, the possible selling of unprofitable businesses and a greater focus on its retail and wealth management ex-US business. Credit Suisse should rapidly amend its new strategic plan and be more aggressive in its restructuring actions. This should be painless for bondholders (but painful for shareholders).

Banks require customer confidence – if that disappears even the most solvent bank can face liquidity issues. Credit Suisse is now facing a liquidity crisis and that needs to be addressed by its home regulator / national government, as confirmed by the move from the SNB to support liquidity. Regulators have been preparing for this type of event: resolvable scenarios have been considered with the group required to submit a will to wind down / break up the institution, if required.

Financial intermediaries in the Swiss financial markets are regulated by the FINMA, which also acts as a resolution authority, helping to ensure stability in the case of an institution getting into difficulties. The FINMA can, at any time, change the Board, the management or / and the strategy of any Swiss bank if it believes the bank could become insolvent. The Swiss law mentions that “FINMA has broad authority to intervene and to take protective or reorganisation measures to protect the bank’s creditors. Such measures may have indirect implications for the shareholders”.

How do you assess the contagion risk from Credit Suisse’s issues and what measures are available to avoid a further escalation of the crisis in Europe?

Given that Credit Suisse is a Globally Systemically Important Bank, regulators will be closely monitoring developments.

Given Credit Suisse is a Globally Systemically Important Bank, regulators will closely watch developments and act to limit contagion to the wider European banking sector. Despite the recent market volatility, the sector is broadly functioning well. A limited widening in the credit spreads (on a historical basis) for other major European banks suggest that the contagion effect of the Credit Suisse case is contained so far.

We expect the majority of counterparty exposure to be collateralised and so we don’t expect material losses from a potential resolution or wind down.

In fact, Credit Suisse is the weakest link in the European banking space at present – no other listed bank is experiencing the same pressures currently to our knowledge. Assurances from policymakers and regulators on the resilience of the rest of the sector may help to contain any systemic risks and spill over effects. However, given the scale of Credit Suisse’s balance sheet and operations, the market is worried about the interconnectedness risk for the rest of the sector. We expect the majority of the counterparty exposures to be collateralised hence we do not expect material losses from a potential resolution or wind down. Since the Great Financial Crisis, the sector is well capitalised, highly regulated and in far better shape compared to the previous crisis. It will be important to monitor liquidity and deposit flows for the sector over the coming periods.

In the European Union, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), adopted in 2014 to reinforce the banking system, gives a framework to “provide authorities with comprehensive and effective arrangements to deal with failing banks at a national level and cooperation arrangements to tackle cross-border banking failures. The directive requires banks to prepare recovery plans to overcome financial distress. It also grants national authorities powers to ensure an orderly resolution of failing banks with minimal costs for taxpayers.” 2

Credit Suisse’s main regulators are in Switzerland, but the bank is also closely monitored by local authorities in countries where the bank has operations. Overall, we expect extensive cooperation between central banks and all the European regulators to limit contagion across the banking sector in Europe. In countries where Credit Suisse is a subsidiary, the bank is classified as a less significant institution and therefore supervised by the respective national authority, and not the ECB. The subsidiaries in the EU will have access to central bank liquidity facilities in these countries. However, in Europe, there is a single rulebook that applies to all banks so it would be subject to the same rules as large banks supervised by the ECB.

How does the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) work?

Over the last decade, regulations have been strengthened to ensure that the regulatory framework addresses any outstanding challenges to financial stability.

The EU's bank resolution rules ensure that a bank’s shareholders and creditors pay their share of the costs through a "bail-in" mechanism. If that is still not sufficient, the national resolution funds, set up under the BRRD, can provide the resources needed to ensure that a bank can continue operating while it is being restructured.

In 2016, the rules were strengthened to complete the post-crisis regulatory agenda by making sure that the regulatory framework addresses any outstanding challenges to financial stability while ensuring that banks can continue to support the real economy with:

- Measures to increase the resilience of EU institutions and enhance financial stability

- Measures to improve banks' lending capacity to support the EU economy

- Measures to further facilitate the role of banks in achieving deeper and more liquid EU capital markets to support the creation of a Capital Markets Union.

In the case of a bank failure, the level of deposit protection in the EU is harmonised at €100,000 (or an equivalent amount in the local currency), and this amount is guaranteed irrespective of the current level of available financial means of any Deposit Guarantee Scheme (DGS). The amount of available financial means of a DGS has no impact on the level of this guarantee and, in any case, alternative means of financing the guarantee are available. These alternative funding arrangements can, for instance, include temporary State financing (which will ultimately be repaid by the DGS). It is worth noting that the likelihood of a DGS being used has been reduced because of the existence of bank resolution tools. The existence of "bank resolution" means that some banks are likely to be dealt with using these new mechanisms and thus limiting the need for DGS support. The existence of the bank resolution regime means that (i) DGSs are less likely to be used; and (ii) even if used, are likely to recover more of the money spent than would have been the case in the past.

How do you assess the market movement of the European banking sector?

In Europe, the bank sell-off is mainly driven by profit-taking and the reassessment of recessionary risks which are not supportive for the sector.

The market movement of European banks seems to be driven by investors taking profits on a position that had become consensus (overweight European banks) . The sector had done extremely well but now the outlook looks uncertain.

The sector is still up 22% since the beginning of October (it was up 45% at the peak, data from Stoxx 600 Bank Index3). So investors that entered the sector last year can still close their positions now and lock in significant profits. And in the middle of this high volatility, it makes perfect sense to do that. But investors are not taking that money and buying defensive sectors with it. Even healthcare, utilities, etc are down. Just less so than banks. Investors seem to be keeping the money in cash and adopting a “wait and see” mode. Waiting to see how central banks will react to the market turmoil and if any more companies will be affected.

More generally, recent events have driven a reassessment of the probability of a recession, the consequences of rate hikes and the yield curve inversion are hitting markets. In a recession scenario, banks are usually seen as a sector to avoid, especially by generalist investors.

What is your overall investment stance?

We reiterate the need to keep a cautious stance on risk assets at this stage as the vulnerabilities built up in this fast-hiking cycle are starting to materialise. On a positive note, government bonds have demonstrated their role as a diversifier in this crisis, with the return of the 60-40 (60% equity – 40% bond) allocation paradigm.