Summary

Executive summary

Since China embarked on economic reforms and opened up its markets in 1978, it has enjoyed a prolonged period of extraordinary growth. A discernible trend emerged in the early 2010s that the country’s growth has peaked and begun to moderate. The focus now turns to the endpoint for this trajectory, and the potential for China to maintain its ascent with a more sustainable growth rate.

This slowdown is structural in nature, propelled by a sharp correction in the housing sector since late 2021 that is still unfolding. In 2024, we expect housing prices in major cities to register faster declines, particularly as the supply of affordable homes increases. The painful process of rebalancing away from an excessive reliance on real estate, compounded by the onset of local government debt restructuring, is expected to place downward pressure on China's growth over the next three to five years.

Nevertheless, it’s not all doom and gloom. The question is not whether growth will slow further, but if China can navigate towards a sustainable future. Aside from real estate, unrelenting debt growth and insufficient investments, are grounds for generating future sources of growth. Productivity lies at the centre of the new growth model, with a renewed focus on technology and the energy transition. However, Beijing needs to mitigate the transition pain and reinvigorate reforms.

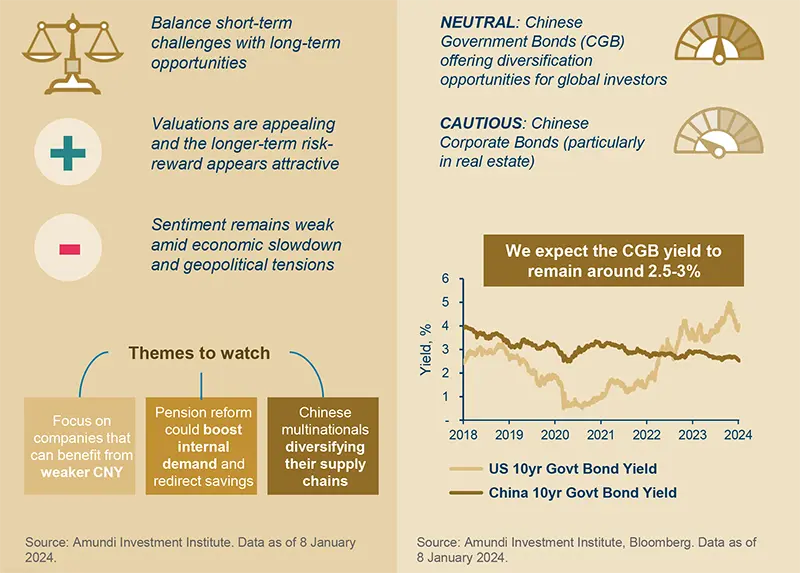

From an investment standpoint, the shift toward a more sustainable growth model presents long-term opportunities in Chinese assets, but it also calls for increased selectivity in the short term to cope with the economic slowdown.

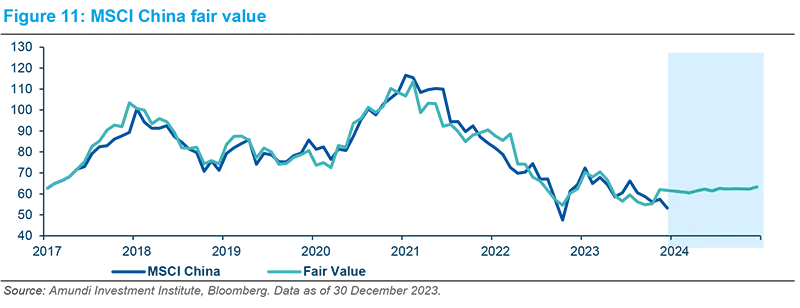

- Equities: we maintain our long-term positive view as we see Chinese equity as a core component of a strategic asset allocation, but we are increasingly selective with a neutral bias short-term amid the weakening real estate sector, about which we are negative (particularly regarding developers). However, valuations are appealing and the longer-term risk-reward appears attractive (especially for the domestic market) even after taking into account another wave of downward earnings revision in 2024, as consensus earnings expectations are still too high. In terms of sector allocation, we favour quality stocks in resilient sectors and companies with the ability to gain market share and that operate in key technologies.

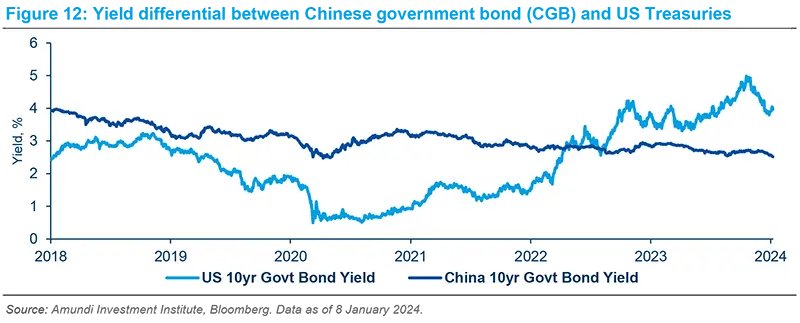

- Bonds: we maintain a cautious view with regard to Chinese corporate bonds. The ongoing deleveraging effort will lead to widening credit differentiation. As for sovereign bonds, we believe that Chinese Government Bonds (CGB) offer diversification opportunities for global investors. Anticipating continuously accommodative monetary policy and a declining neutral rate, CGB yields will remain steadily low.

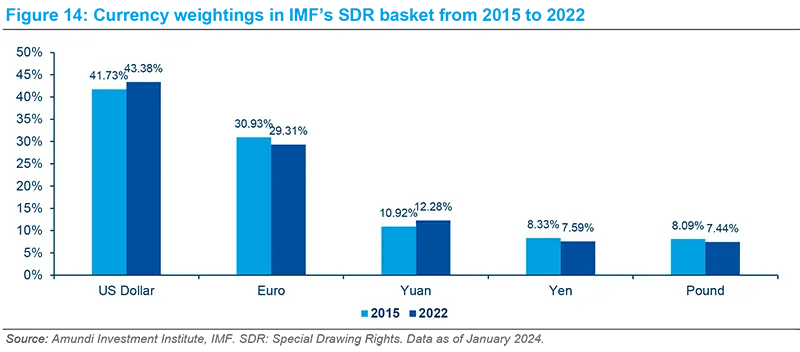

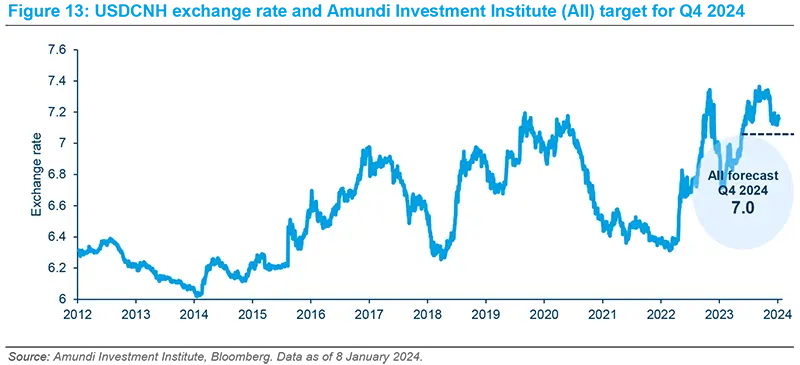

- Currency: the Fed pivot and PBoC’s monetary policy choice are the key determinants for the RMB outlook in 2024. We expect the currency to have a mild appreciation against the dollar amid the narrowing policy rate gap. Over a longer horizon, the RMB will be increasingly used as a settlement currency in trade. Further globalisation of the RMB will hinge on its financing and investment functions, where China’s financial liberalisation and global integration will play an essential role.

The goal of Chinese policymakers is to manage the economic transition; this suggests deleveraging has become the new priority over the old growth-centric approach.

Investing in China 2024

2024 - The pivot towards a new growth paradigm

Productivity holds the key

Some clouds in 2024 China macro outlook

Equity Views

Fixed income views

A long-term view: a new growth paradigm

Growth decelaration underway

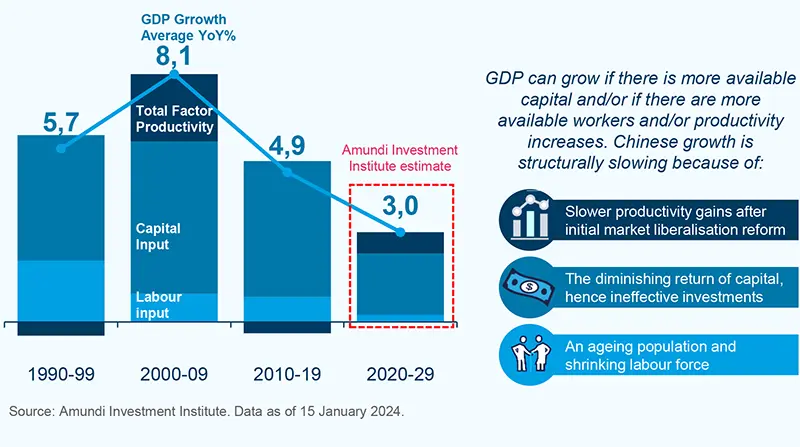

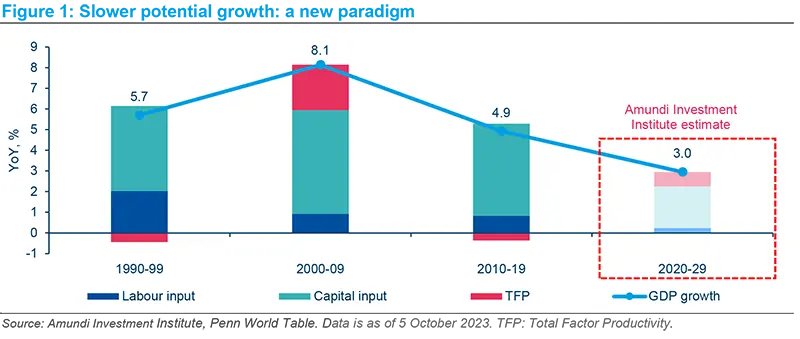

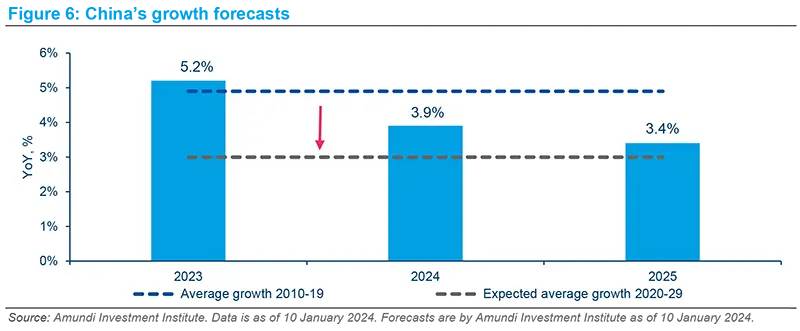

China has been among the world's fastest-growing economies since the 1980s when it began its reforms and shifted to an open-door economic policy. However, economic growth has started to slow after four decades of impressive economic success. The deceleration trend of Chinese GDP growth is not new: after roughly 10.5% per year during the 1990s and 2000s, annual average GDP growth slowed to around 8% during the 2010-2015 period, and then to 6.6% in the four years before Covid-19.

There are several factors explaining this already observable deceleration, among them are:

- An ageing population and shrinking labour force.

- The diminishing return of capital, hence ineffective investments.

- Slowing productivity gains after its initial market liberalisation reforms.

In particular, the high-single-digit growth in the early 2010s was largely dependent on investment and credit. But the side effects have become too big to ignore for policymakers. As domestic fragilities built up, leverage in the financial system increased and inequalities skyrocketed.

Towards a sustained future

The high-growth model, once propelled by investment, low-cost manufacturing and exports, has reached its limit, necessitating a transition. The current economic downturn presents risks, yet it also offers opportunities embedded within a new paradigm for growth and development.

Despite facing three significant challenges – a demographic shift, debt and decoupling – we expect China to sustain a 3% growth rate.

"The current economic downturn presents risks, yet it also offers opportunities embedded within a new paradigm for growth and development."

The first demographic dividend, generated by working-age population growth, is long gone. The working-age population will continue to decline over the next half-century, translating into lower potential growth. The second demographic dividend, achieved through investments in physical and human capital, is usually larger than the first1. The prevailing low fertility rates in East Asian economies provide important lessons: it is difficult to reverse the demographic profile over the long run but it pays off to invest in human capital and to tap into the talent dividend, where China still has a notable gap (25%) compared to East Asian economies.

While demographic trends are relatively consistent and predictable in the long term, capital input growth is largely a matter of policy, particularly in terms of debt management. The real estate deleveraging saga has starkly demonstrated that Chinese policymakers are averse to inflating away their problems. As resources shift from real estate to strategic sectors, such as advanced manufacturing, we anticipate a marked reduction in capital stock growth – from 11% in the decade of 2010-2019 to an expected 5% in 2020-2029.

Productivity holds the key

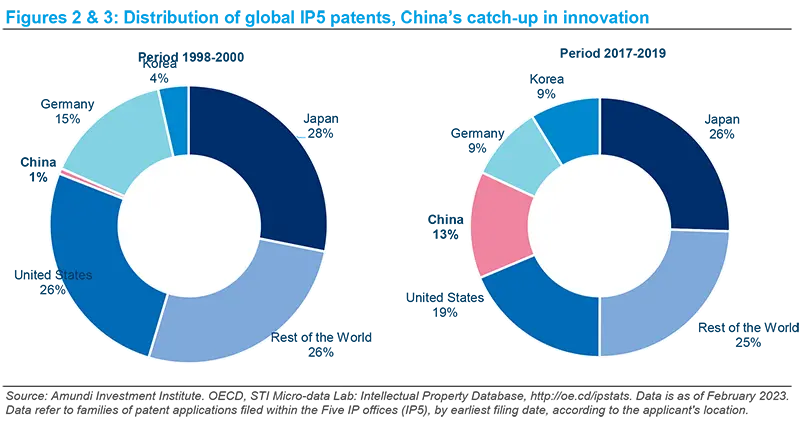

China's rapid advancement in global innovation is evident. The country has risen to prominence in several metrics, including the number of top-cited researchers, scientific publications and global patent shares.

“Innovation has been prioritised at the national level, aiming to transform China into a technological powerhouse and transition from low-value-added manufacturing to an economy based on innovation.”

The critical question is whether China can maintain its upward trajectory in the face of intense strategic competition globally, notably as the West prioritises national security over economic interests and pursues a de-risking strategy.

Decoupling could impact China's growth through productivity, and to a lesser extent, through capital input as foreign direct investment (FDI) retreats. Nonetheless, we expect China to maintain a steady pace of technological progress, supported by its leadership in several crucial technology sectors, as well as the government's focus on basic research and the semiconductor industry.

However, it's often overlooked that technological advancement doesn't automatically translate into productivity gains. For these gains to materialise, structural reforms and institutional changes that set the right incentives are essential. A nation with leading scientists may not effectively disseminate technology across its society and can still experience productivity loss. Boosting total-factor productivity (TFP) through catch-up growth can be significant and beneficial, but further reforms and economic liberalisation are prerequisites for such progress.

Box 1: China is already a leader in certain technologies

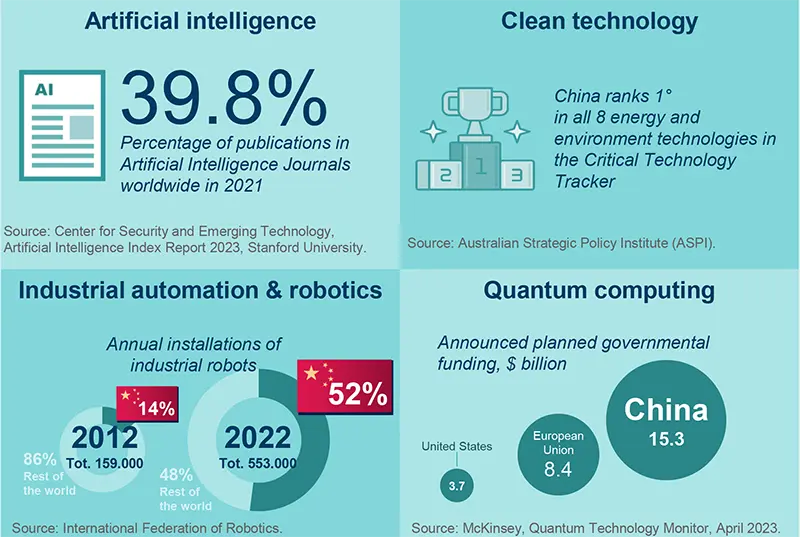

The vibrant private sector, its massive manufacturing base and skilled labour generated a unique technology advancement pattern in China. In this regard, process innovation is as important as original inventions, and the main driver for industrial upgrade.

Policy-wise, we believe that China will continue to:

- Pursue a technology autonomy and increasingly rely on its domestic market

- Move up the global value chain, with axes in clean energy, AI, semiconductors, Electric Vehicles and digitalisation.

- Seek industrial policy and regulatory reforms to increase productivity growth.

China is quickly closing the gap with the US in AI research. Chinese scientists now publish more papers on AI and secure more patents than their US counterparts. Although the US remains the leader in designing chips for AI systems, China is leading in terms of AI applications such as speech and image recognition. Part of China’s AI success is also down to its large population, which enables companies to gather and harness huge amounts of data. Some household names are taking the lead in evolving the AI research agenda.

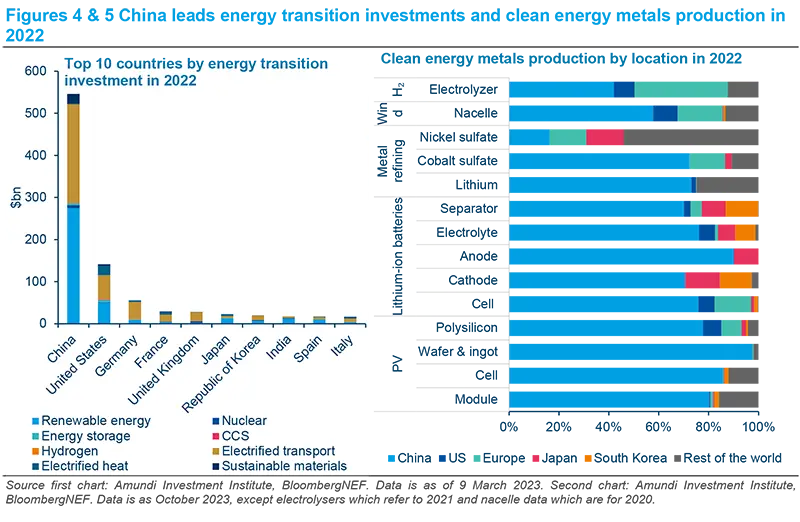

China has been the biggest investor globally in clean energy over the last decade and it is now the largest producer of solar panels, wind turbines and electrical vehicle batteries in the world. It holds almost three-fourths of the world’s manufacturing capacity for lithium-ion battery cells and controls even more of the supply chain before final assembly. Through its Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese companies are becoming key exporters of these products around the world.

China is poised to lead the world in the automation economy; with a shrinking working-age population which is set to accelerate, the demand for industrial automation will continue to grow rapidly. China is already the biggest market for industrial robotics accounting for over 50% of new installation of industrial robots worldwide in 20222. China is also becoming a leading global producer of advanced robotics. The Chinese government makes no secret that it would like the nation to become self-sufficient when it comes to industrial robots.

2. World Robotics 2023 Report, September 2023.

Chinese researchers have been leading the field of quantum communications as well as quantum computing and hold more patents across the quantum field than their US counterparts. A team of Chinese scientists built the most powerful quantum computer in the world last year, capable of performing at least one task 100 trillion times faster than the world’s fastest supercomputers. Quantum computers and communications are nascent technologies and unlikely to be of practical use for years to come. But fully-fledged quantum networks could provide unhackable channels of communications, and a powerful quantum computer could theoretically break much of the encryption currently used to secure emails and internet transactions. They would therefore have vital national security applications.

China technological advancement

China leads energy transition investments

Energy transition: another element to achieving higher-quality development

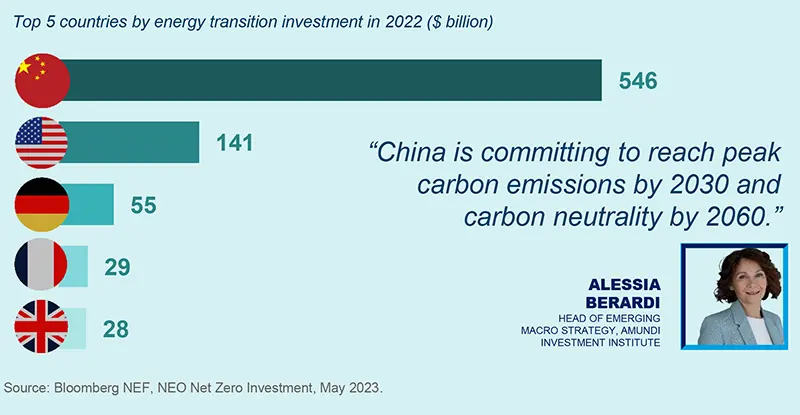

The Chinese objective to achieve high-quality development also relates to the green transition. Growth rebalancing is having a positive impact on the domestic economy as it could speed up the energy transition, avoiding the negative effects of climate change.

China strives to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, 10 years later than the EU or the US. In the meantime, it leads investment as well as R&D in the energy transition globally: the country spent $546 billion in 2022 on energy transition investments, which included solar and wind energy, electric vehicles and batteries, accounting for almost half of global expenditure. The industry is gaining strong public support to reduce fossil fuel dependence and increase electrification.

China continues to lead clean-technologies manufacturing, especially in electric vehicles, solar panels and batteries. The US Inflation Reduction Act and the European Green Deal aim to localise new energy supply chains and reduce their reliance on China. However, given the urgency to act on climate change, and given China’s superiour cost basis and technology advantage, we believe China will maintain its strong leadership in this key industry, furthering growth potential over the long run.

2024: in the shadow of multi-year deleveraging

The post-pandemic recovery has been tepid and disappointing, impacted by a sharp correction in the Chinese housing sector. China’s economy is projected to end 2023 with a growth rate of just over 5%. Throughout the year, market expectations for policy stimulus have been realigned in accordance with Beijing's long-term vision, which shifts away from a singular focus on growth and incorporates new considerations including national security.

While there have been modest signals of recovery, overall growth remains sluggish and we have turned more cautious on the Chinese economy, particularly over the medium term. Our growth projections for 2024 and 2025 diverge from the consensus, as we expect a rapid economic transition towards the lower 3% gear. This shift comes as China grapples with secular challenges including demographic ageing, diminishing capital returns and geopolitical fragmentation.

Easing measures: too light for a secular downturn

Beijing escalated fiscal, housing and monetary policy easing at the end of 2023. This initiative was not a one-off stimulus, it will be a multi-year commitment with final numbers likely to surprise on the upside. However, these efforts are a rather responsive defence to mitigate the impact of a significant ongoing constraint – debt discipline. The overarching force of debt discipline will overshadow easing measures, driving growth down further.

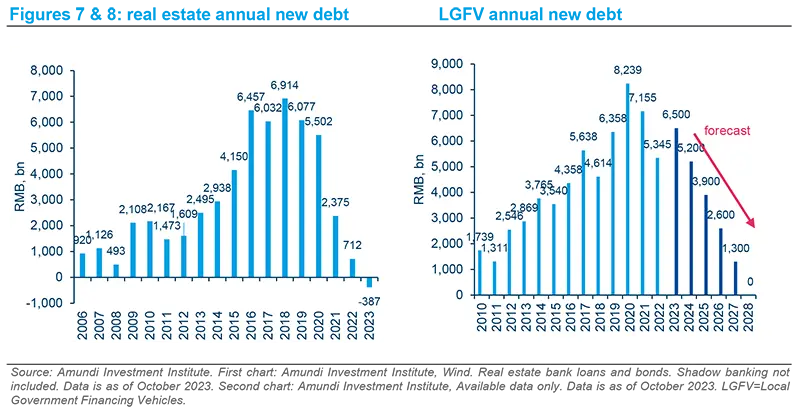

The deleveraging effort began in the real estate sector in late 2021. Over three years, RMB6 trillion of new credit to the sector evaporated, plummeting from over RMB5.5tn in 2020 to -387bn in Q1-Q3 2023. The remaining developers are still grappling to stay solvent.

“This overarching force of debt discipline will overshadow the easing measures, driving growth down further. We expect a rapid economic transition towards the lower 3% gear.”

Attention has now turned to Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs)3, with tightening measures starting in late 2023. Unlike real estate developers, LGFVs benefit from government fiscal support and a higher degree of policy leniency. Immediate deleveraging within this sector is not anticipated; however, the growth of new debt is projected to decelerate from the current rate of RMB 6 trillion per annum down to zero or could even be negative by 2028.

Between 2017 and 2020, real estate and LGFV collectively accounted for half of China’s annual new credit (51%), equivalent to 13% of GDP. This marked a dramatic increase from the less than 15% share that real estate held in 2007-2009, a time when the concept of LGFV was non-existent.

Reversing these two excesses in sequence will require the formal government sector to leverage up, and the fiscal deficit to remain expansionary for longer. Policymakers cannot afford to passively wait for credit demand in other sectors to grow. In fact, in the process of dealing with real estate excesses, we have seen a strong window of guidance for the banking sector to increase lending to the manufacturing and rural sectors.

3. A special type of entity that thrived after 2009 as the central government opened the back door for local SOEs to get around the strict fiscal rule, leverage state assets (e.g. land as financial collateral), raise funding from the market and invest in infrastructure projects.

Consumer: a slow burn, not a swift recovery

While the entire economy will have to deal with the reversal of excessive leverage, the impact will not be uniform, with households bearing the brunt of the strain. The average Chinese consumer is faced with the dual blow of slower economic growth and exclusion from the latest round of fiscal stimulus. The 2023 supplementary budget dedicates all spending (0.8% of GDP) to infrastructure, offering no direct relief to consumers.

Compounding the issue is a bleak labour market outlook and the looming onset of a wealth shock. Despite avoiding significant price corrections so far, the real estate sector is on the cusp of a downturn. The combined effect of shrinking incomes and falling property values is likely to result in an uptick in mortgage defaults.

Unless there is a shift in policy to support consumer spending, the gradual erosion of consumption will persist. A historical parallel can be drawn with Japan from 1985 to 2003, where the middle class contracted and income distribution skewed, leading to a more polarised "M-shaped society."

Currently, the Chinese government's focus remains on supply-side policies, emphasising its manufacturing prowess and supply chain resilience, with little attention being paid to consumer-driven demand stimulus. This preference has resulted in broad disinflationary pressure. While there is no strong evidence to suggest that China is entering a period of deflation, mild underlying inflation is anticipated.

Navigating this economic shift amid relatively high leverage is a delicate balancing act, revealing financial vulnerabilities. Yet, a systemic financial crisis is not inevitable and any debt crisis is likely to differ from past financial upheavals witnessed in emerging markets (like the 1997 Asian crisis) and developed markets (such as the Lehman Brothers and the Eurozone sovereign debt crises). This distinction is partly because much of China's debt, both public and private, is denominated in local currency, unlike many emerging markets. Additionally, Chinese authorities retain considerable discretion to distribute costs among stakeholders and to manage the failures of economic entities on a case-by-case basis.

Real Estate: half-way through the downturn

Property sector remains a drag on China's economy

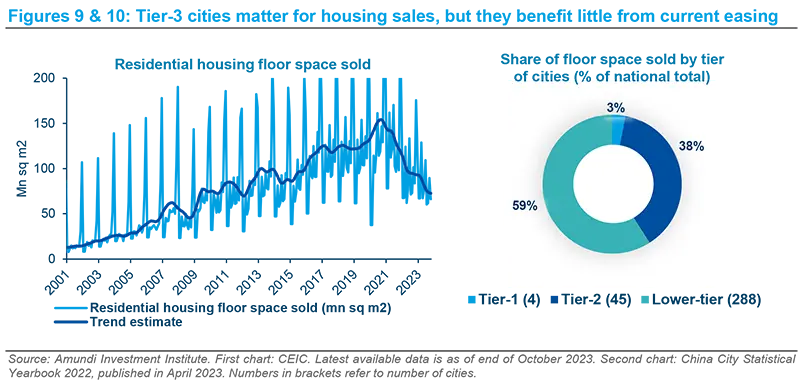

The sharp correction in the housing sector is not over yet. Given the restrained easing and deteriorating supply/demand dynamics, further steep declines in home sales are likely in 2024-25 (a 10-15% fall in volume each year) before the momentum stabilises and the market enters a gradual decline mode.

The recent announcement to provide refinancing help to developers reduces the tail risk of additional big-name defaults in 2024, but it has little impact on reviving housing demand. The real estate sector has escaped a meaningful price correction so far. In 2024, with a record number of listings in the secondary market and an expected increase in affordable public housing supply, we will start to see home prices drop more significantly, especially in large cities.

Beijing’s objective is to engineer a controlled decline for the real estate sector, not to revive the sector. Hence, any easing of housing policy has been tactically restrained to support only rigid demand and implemented in a city-specific manner. Lower-tier cities, having exhausted their policy room since end-2022, are benefiting little from the latest easing measures and the relaxation of purchase restrictions in Tier-1 cities will further widen the disparity between large and small cities.

Moreover, it’s becoming an increasingly herculean task to counter the structural drop in demand using cyclical easing measures. Urban household formation, the key driver of rigid demand, is naturally decreasing over the long term and is projected to reach 7mn units in 2026 before dropping to 4-5mn by 2030. The notion of a long-term demand floor appears to be misleading, as the market is set to shrink.

The risk of additional negative credit events among the remaining private real estate developers cannot be ruled out. This warrants a cautious approach towards the housing sector. Given the limited exposure to private developers in the banking system, we don’t think the crisis will be a systemic one as was the 2008 Great Financial Crisis in the US. In addition, the Chinese financial system is administered with strong state intervention. The loss could be digested over multiple years.

“Although the sharp correction in housing sector is not over yet, we don’t think the crisis will be systemic. Moreover, China's property troubles could be digested over multiple years.”

Market views beyond the short-term outlook

View on the Chinese equity market

We remain neutral to slightly constructive on the Chinese equity market, although we have adopted a more selective approach to our Chinese market exposure in the short term.

There are two main reasons for our current caution:

- The magnitude of the macro-economic recovery has been disappointing thus far and there remains the possibility of further downside risk to GDP growth (given the government’s piecemeal approach to easing will not be enough to revive growth), and further downside risk to earnings expectations as 2024 market expectations still look too high.

- Geopolitical risks are also an emerging threat to equity market performance, and one we see persisting through to this year’s US elections.

Balancing positive factors:

- On the flip side, the macroeconomic downside may be offset by significant excess household savings accumulated during the Covid-19 period being deployed into the wider economy.

- Valuations: macroeconomics and policy measures aside and focusing on valuation, we note that the Chinese equity market (i.e. MSCI China is approx. 9.9xfwd P/E (source Bloomberg as of 12 Jan 2024) and trading near historical lows) looks attractively valued following the recent pull-back. However, after taking into account a possible further downward wave of revisions in terms of earnings expectations, the market may seem attractively valued but not cheap enough to trigger a buy.

- The Chinese ‘policy put’: a pro-growth government stance with the capacity to further support the property and private sectors. It is a powerful driver for markets, as seen in some market performance for example during the announcement of the Government’s initiative to cut the stamp duty applied to equities as well as to cap brokerage fees. Nonetheless, we note that some policy measures revealed recently lacked granularity (or scope) and have failed to restore confidence and backstop the market.

Example of “Policy Put”:

A national consumption promotion package – notably, the third one since mid-June, was recently released albeit lacking the fiscal backing necessary to come to fruition. Similarly, Tier-1 cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen have recently released statements echoing the MHURD’s (Ministry of Housing & Urban Redevelopment) supportive stance towards domestic real estate – including lowering the down payment requirements for first-home buyers and reducing the stamp duty charges for second home buyers, yet have failed to pass policy measures echoing their statements to date. Going forward, and over the coming weeks, we expect the Government’s various proclamations – i.e. consumption stimulus, SME tax cuts, mortgage rate reductions, property policy support, FX stability and the potential for further monetary easing through RRR cuts – to be debated and tested by the market, driving further market volatility.

From a sector standpoint

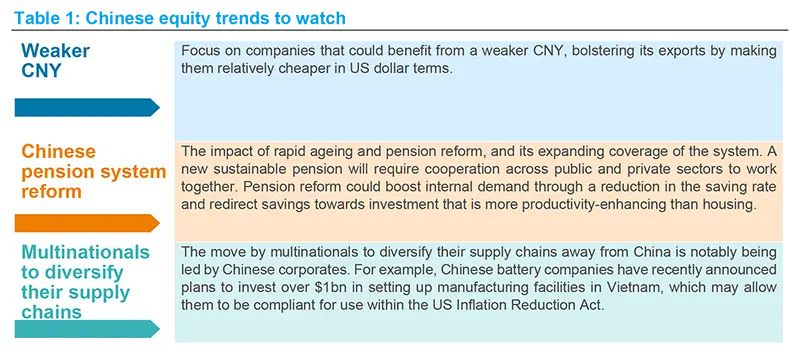

We have become more selective in Chinese equity, focusing on areas where we see demand remaining resilient amid an uncertain macroeconomic backdrop and companies that have the ability to gain market share, as well as companies that have the ability to innovate (whether in process, product or cost structure).

- We are cautious on Industrials (where we see an unprecedented wave of impending supply within the solar and renewable energy supply chain, but are positive on select pockets – i.e. industrial automation plays).

- While we continue to remain positive on certain names within the EV/battery sector, we see large parts of the battery component sector heading into oversupply, so here we prefer to stick to the sector leaders in terms of costs and technology, with conservative expansion plans, who should continue to gain market share as smaller local competitors exit the industry.

- Separately, we remain cautious on banks, insurance, IT and real estate.

- We are more constructive within consumer staples, healthcare and consumer discretionary stocks, albeit remaining selective. In the consumer space, we prefer the companies catering to trends such as travel and luxury goods as demand is either more resilient or was pent up and post-reopening has not been entirely released yet (due to capacity constraints, e.g. outbound flights)

- We remain positive on energy and communication services.

- Going forward, we believe that longer-term risk-reward may favour domestic Chinese A-share markets (relative to offshore-listed Chinese equities in HK and elsewhere) amid the gradual escalation of geopolitical risk as well as the enormous domestic liquidity pool to be deployed once confidence recovers. Short-term, offshore-listed Chinese equities might offer more upside in the case of more decisive fiscal easing.

In conclusion: we think that the downside is fairly limited in Chinese stocks, on the back of cheap valuations, low investor positioning and no systemic risk; the rapid deterioration in the property market, LGFVs and Trusts should continue to trigger a broad array of stimulus announcements. However, the likelihood of a corporate earnings upcycle relies on the revival of the almighty property market and decisive fiscal easing from the Government, which might not happen as quickly as investors want as systemic risk remains low; hence our idiosyncratic approach and we are somewhat defensive in our stock selection, which favours higher quality names.

“We think that the downside is fairly limited in Chinese stocks, on the back of cheap valuations, low investor positioning and no systemic risk.”

Key trends for China's bonds market

Regarding EM fixed Income, we have been defensive on Chinese assets over the quarter and we are cautious on Chinese hard currency bonds, local rates and FX.

China government bonds view

We expect Chinese local government bonds’ low beta compared with US Treasuries to continue despite the growing valuation gap between the UST 10yr versus the CGB 10yr yields. With the renewed PBOC easing bias to simulate the real economy, we expect the CGB yield will remain anchored around 2.5-3%. Technicals are positive for CGBs, investors are lightly positioned in CGBs and non-resident holdings of CGBs remain very low, below 10%4, while CGBs remain a key investment instrument for local financial markets.

4. EM Local Currency Bond Holdings Monitor, by IMF January 2024.

More cautious on China’s credit market

Although we are generally cautious on Chinese credit owing to the short-term outlook for the Chinese economy, there are pockets of value in specific issuers. However, a careful approach towards credit quality is necessary in light of recent credit events as well as potential tail risks in the current economic environment.

From a sector standpoint

The larger global sectors in focus are:

- Real estate – it remains a sector where there is little optimism for the moment; ongoing sales decline YoY, a lack of progress on restructuring initiatives in external bond markets combined with a lack of game-changing stimulus in the underlying markets themselves has left the sector without major positive catalysts. Furthermore, some of the top developers – that had formerly been seen as potentially resilient, such as Country Garden – have seen a sharp reversal in fortune as the structural downturn in the industry continues to take its toll.

- Asset management companies (AMCs) – the sector continues to be a point of concern after a profit warning from one large company and the postponement of earnings from another. The profit warning was broadly in line with expectations for both investors and rating agencies but evidenced the impact of broader economic pressures and uncertainties relating to the underlying exposure of these companies. For now, companies are expected to meet capital requirements and there remains the possibility of further supportive actions from the Chinese government, but risk on ratings may remain. Some issuers have also proactively addressed their debt burden through sizeable bond buy-backs. Therefore, we are highly selective overall, but our bias is to reduce overall risk further.

- TMT and utilities: we are more constructive on selective names within technology and utilities. We see these issuers’ credit profiles remaining strong on the back of idiosyncratic improvements while being more insulated from top-down headwinds.

Outlook for Renminbi

The Chinese currency weakened by 3% against the US dollar last year reflecting China's economic troubles. That said, with the Federal Reserve now pivoting to a new monetary cycle, we think the USD’s bull trend is behind us. This should limit how much upside for USD/RMB will be extended. The market is also short the RMB, which again serves as a positive technical for the currency.

Over a longer horizon, especially given the recent extension of BRICS, we think the RMB will be increasingly used as a settlement currency as well as being the third largest currency in the IMF SDR basket. The significance of this evolution is that from a global reserve allocation perspective, there is room for allocations to RMB assets to increase over the long term.