Summary

Key Takeaways

- Geopolitical multipolarity is set to persist, with heightened risks of miscalculation, shifting alliances, and military build-ups driving uncertainty and security risks.

- The US is using tariffs to pursue foreign policy goals, but it remains constrained. It is also waking up to its dependence on China’s rare earths, while Russia, broadly self-reliant, has ignored Trump’s demands to end the war. These dynamics highlight the limits of US leverage in a multipolar world.

- Europe and emerging powers are recalibrating their positions, reinforcing the trend toward ‘The Great Diversification’ across trade, security, and resources.

In line with our long-standing view that the level of geopolitical risk will rise for the remainder of this decade, the last few months have revealed an accelerated transition towards a multipolar world.

Multipolarity is one of the most unstable political systems because it assumes a high degree of uncertainty about the intentions of other states, increasing miscalculations, competition, and leading to frequently shifting alliances. It also accelerates military build-ups.

Since US President Donald Trump took power, it has become evident that raw power (control over minerals, energy, food) and military strength are what counts.

The US is using tariffs to achieve foreign policy goals and to increase US power, while military protection serves as leverage over allies to force them to give in to US demands. Therefore, more tariffs are likely, impacting global growth, inflation, and uncertainty.

However, the US is no longer the hegemon, limiting what it can do. Instead, those with critical resources and military power now have the leverage to offset US demands. The US will dissuade alliances from being formed against it and efforts to de-dollarise, but success will be limited.

As a result, the US is waking up to its dependence on China. China began to limit rare earth exports earlier this year, with a direct impact on US and EU manufacturing. That dependence limits how much the US–China relationship can deteriorate in the short term. However, the relationship is unlikely to change markedly given that this is a Great Power Competition, even if there is eventually a limited trade deal.

The US is waking up to its dependence on China.

Russia, broadly self-reliant, has ignored Trump’s demands for an end to the war. Instead, Russia will continue to test NATO with ‘grey-zone’ intimidation tactics. We continue to expect no ceasefire for the next several months. Russia is unlikely to abandon its maximalist war goals yet. The US, with mid-term elections approaching, remains unlikely to implement painful enough secondary sanctions. This is not to say that the US will not implement any secondary sanctions, but these will be limited to avoid higher energy costs in the US.

Geopolitical hedging in a multipolar world

Middle powers (especially in emerging markets) feel vindicated for hedging their geopolitical relationships (India, Brazil). India has leverage as it represents an alternative to China. While the US–India relationship is currently frosty, there are avenues for things to improve as Modi will be in the US later this year and the US has no interest in pushing other powers closer to China.

The EU is struggling to position itself in this new geopolitical order. It lacks military power and is reliant on other countries for key resources. The EU will either continue to influence Trump with the purpose of damage control or push through economic, fiscal, and political reforms. The political constraints make the first option more likely, at least until Germany’s military build-up and geopolitics make bolder reforms easier.

As a result of these dynamics (as well as intensifying domestic political turmoil in the US), governments and investors will continue to seek to lower their dependencies. ‘The Great Diversification’, as we have called it before, across geographies, asset classes, currencies, commodities, trade and security ties, will continue. Recent efforts by the US to secure rare minerals access in the Congo are an example, as are European efforts to finalise trade partnerships with Mexico and Mercosur.

US–EU energy procurement agreement: symbolic or achievable?

| ||

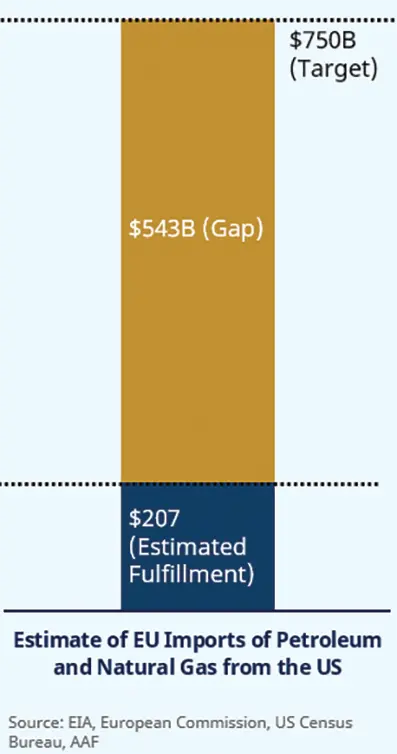

The European Commission has made an ambitious pledge to buy US energy— $750 billion over 3 years, or $250 billion per year. This is larger than the EU’s total energy imports globally. We expect this to be a tall challenge and that it will very likely take more than a year to get to the $250 billion per annum target. With respect to imports of LNG, we would note that currently the EU does not have the storage capacity to purchase the required amounts within this $250 billion envelope. Similarly, the US currently does not have the capacity to supply the required amounts of LNG. |

| |

Lorenzo PORTELLI | ||