Summary

- The centre-right Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union won the German elections held on February 23 with 28.6% of the votes, putting CDU leader Friedrich Merz on track to be the next Chancellor. His first job will be to form a coalition government.

- Negotiations with the Social Democrats, which came third with 16.4% of the vote, will focus on bridging differences on issues such as fiscal reform and domestic policies. A change in the fiscal stance is likely, with more spending on defence, but may not result in a major stimulus.

- Any reform of Germany’s debt brake or the creation of a special fund will take time given the existence of a blocking minority and is therefore unlikely to affect growth before 2026.

- Merz is currently discussing with the SPD the possibility of approving up to €200 bn of special defence spending before 24 March. Given the blocking minority, it would be technically possible to pass such a measure with the outgoing chamber, i.e. before the start of the new legislature (24 March). Summoning Parliament for an emergency session under such conditions has not happened since 1998, when Germany had to make decisions concerning the war in Yugoslavia.

- Given more debt issuance is likely, German bond yields may have to rise further if they are to become more attractive. The blue-chip DAX appears reasonably valued despite its strong performance over the past year and could benefit if key reforms are implemented.

Election Results

The centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party, the Christian Socialist Union (CSU), won the German election with 28.6% of the popular vote. CDU leader Friedrich Merz is therefore set to be the next Chancellor and will lead coalition talks to form a government at a time when Europe’s biggest economy faces economic, trade and geopolitical challenges.

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) doubled its voter share to 20.8%, broadly in line with polling, but had hoped to secure more votes. While in theory, the CDU/CSU could govern with the far-right AfD, Merz has ruled this out. His most likely coalition partner is therefore the Social Democrats (SPD), even though the centre-left party performed poorly with only 16.4% of the vote. Outgoing Chancellor Olaf Scholz has said he won’t take a frontline role in his party.

The Greens came in fourth with 11.6%, followed by far left party die Linke (8.8%). Both the liberal FDP and left-wing BSW fell short of the 5% threshold to enter the Bundestag. Die Linke emerged as the clear outlier performing strongly as a result of a strong pro-migration campaign.

2025 election results – Distribution of parliamentary seats

What are the coalition options and how long could negotiations take?

Given the tensions that brought down the last government, which was a three-party coalition, preference will be given to a two-party coalition to limit the amount of compromise necessary. The most likely coalition is between the CDU/CSU and the SPD.

In Germany, coalition negotiations typically last between two and three months. The new government is likely to take office by April/May, depending on the complexity of the negotiations.

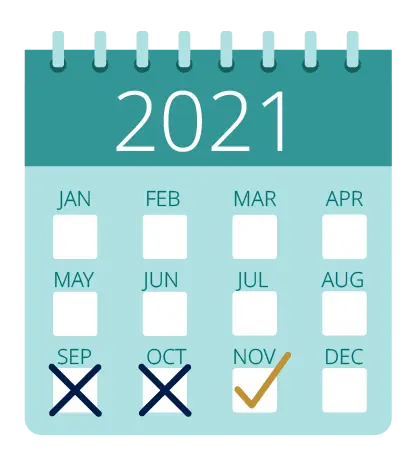

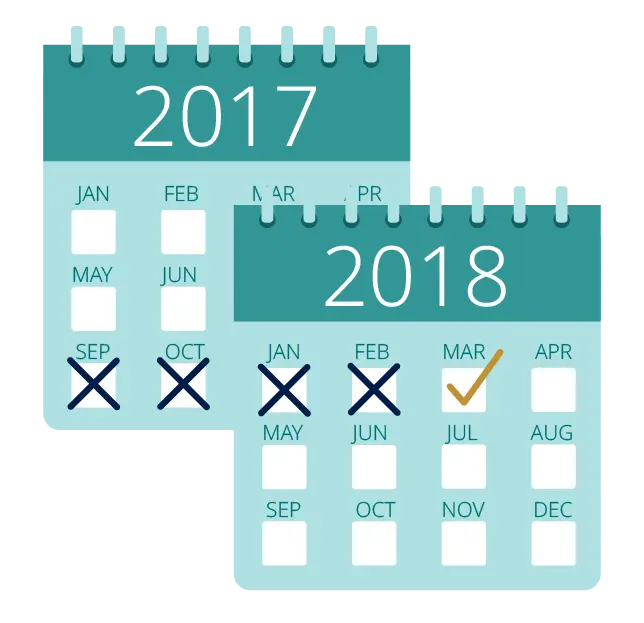

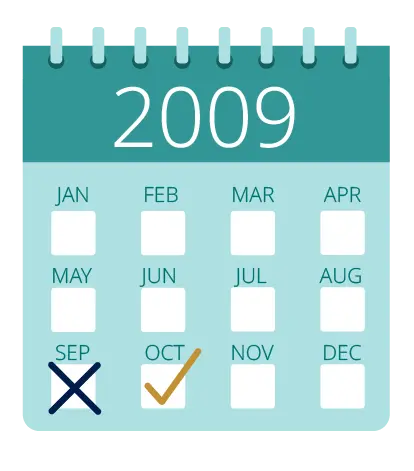

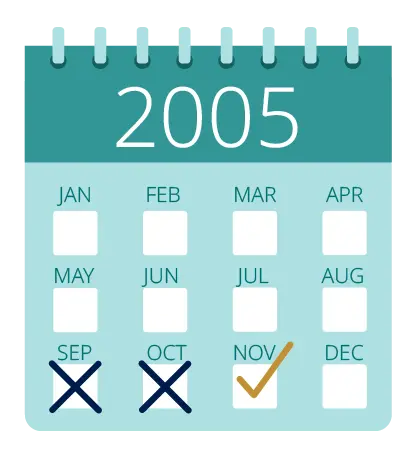

Usual duration of coalition negotiations in Germany

| Traffic light Coalition The elections took place on September 26, 2021, and the coalition agreement between the SPD, the Greens, and the FDP was presented on November 24, 2021, meaning negotiations lasted approximately two months. |

|---|

| Grand Coalition The elections were held in September 2017, but due to complex negotiations, including the initial failure of talks for a "Jamaica" coalition (CDU/CSU, Greens, FDP), the final agreement between the CDU/CSU and the SPD was only reached in March 2018, about six months after the elections. |

| Grand Coalition After the September 2013 elections, the CDU/CSU and the SPD took about three months to form a grand coalition, with the final agreement concluded in December 2013. |

| CDU/CSU - FDP Coalition The elections took place on September 27, 2009, and the coalition agreement between the CDU/CSU and the FDP was finalized on October 24, 2009. Angela Merkel was sworn in as chancellor for a second term on October 28, 2009, meaning negotiations lasted approximately one month. |

| Grand Coalition The federal elections were held on September 18, 2005, and the formation of a grand coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD took time due to the tight results. The final agreement was reached on November 11, 2005, meaning negotiations lasted about two months. |

How much could policy change?

The centrist parties’ election manifestos took different stances on issues ranging from fiscal reform to domestic politics. But they were broadly aligned on EU policy and attitudes towards the United States.

| The program emphasizes maintaining the debt brake, reducing taxes for low- and middle-income earners, and implementing strict security measures, including a zero-tolerance policy on crime and enhanced border controls. The program also advocates a strong stance on migration, including deportations and reduced social benefits for asylum seekers. |

| It supports Ukraine, strengthening transatlantic relations, and calls for increased military spending and cooperation within NATO. Additionally, it seeks to enhance Germany's role in the EU while rejecting joint European debt liability and advocating for a more competitive European market. Merz will also seek to strengthen transatlantic relations, but this will be difficult given expected US policies towards the EU. Merz is likely to work with the United States through EU channels, try to mitigate trade conflicts and enter new agreements with countries in Asia and Latin America. |

| It reduces European bureaucracy, increases competitiveness, and revitalises relations with France and Poland. |

| The CDU/CSU platform specifies spending of 2% of GDP on NATO and CDU leader Friedrich Merz suggested during a pre-election televised debate that such expenditure would 'probably reach 3%' of GDP. The CDU also seeks a gradual reintroduction of mandatory military service and aims at strengthening the defence industry with more European cooperation in arms production. |

| The SPD’s programme criticises the current debt rule and proposes reforming it to allow greater public investment, especially in infrastructure and innovation. The SPD wants to increase worker protection and the minimum wage. It also seeks income tax reform with targeted tax relief for low- and middle-income earners. The party calls for reduction of electricity costs, support for renewable energies, and incentives for ecological transition for businesses and households. |

| The party would like to continue to support Ukraine through military and humanitarian aid while avoiding military escalation between NATO and Russia. It calls for another 100-billion-euros fund for defence and a target of 2% of GDP for military spending. The SPD also wants to diversify Germany’s trade partners to reduce dependence on China and the United States. |

| It supports reform of the single market and European integration and wants to strengthen Europe’s industrial base. The SPD emphasizes cooperation with France in several areas, notably industrial policy and energy transition. The SPD proposes Europe pursue strategic independence to counter the protectionist policies of the US and China. |

| It criticises the current debt rule and proposes reforming it to allow greater public investment, especially in infrastructure and innovation |

Given their different stances, much will depend on the coalition contract. However, fiscal reform is likely, with the degree of change depending on negotiations.

Overall, we can expect the following policy changes: Germany is likely to increase defence spending. Reducing welfare spending may be tricky given the SPD’s pledges. Germany is likely to have to play a more dominant role when it comes to the Russia/Ukraine conflict, in particular in defence, but also in managing relations with Russia after any ceasefire. The US may also want to bring Russia closer to the US and Europe if it wants to distance Russia from China. Given Russo-German history, it is likely that Germany will play its part, not least because the prospect of cheaper energy prices will be a welcome relief for the German economy. However, the stance may pose political difficulties and will take time.

On foreign policy, the next government is likely to prioritise EU cooperation and the diversification of trade relationships. It will take a nuanced approach to China, as it seeks to ‘de-risk’ while avoiding another trade war given a trickier relationship with the United States. Germany is unlikely to fall out of line with other European countries when it comes to the US.

Economic and fiscal Outlook

What is the economic and fiscal outlook?

The German economy, which was in recession for the second year running in 2024, is the weakest economy in the eurozone. Tightening financial conditions, rising energy prices and weakening foreign demand (particularly from China) explain the poor economic performance. Structural problems pre-date these issues. There is a huge backlog of investment and ageing infrastructure. Meanwhile, a shortage of skilled labour, an ageing population, and low productivity mean that potential growth is under pressure.

Uncertainty over tariffs has been weighing on confidence and domestic demand since the start of the year. As a result, the economic outlook for 2025 is bleak. The government has recently cut its growth forecast for this year to 0.3% (compared with the 1.1% it expected as recently as October). And the Federation of German Industries (BDI) is even more pessimistic, forecasting a further contraction in GDP this year of around 0.1%.

The next government will therefore have to tackle the economic concerns that largely dominated the election campaign. Some of the reforms proposed by the CDU to boost growth have no budgetary cost (e.g. cutting red tape). However the parties that will form the next coalition recognise that additional fiscal resources will be needed.

There are two ways for the next government to raise funds:

- A reform of the constitutionally-enshrined debt brake rule

- The use of one or more special off-budget funds (for defence and/or infrastructure)

In both cases, a two-thirds majority in both houses of parliament is required and the choice will be based on political, rather than economic, calculations. The CDU, the SPD and the Greens, who all favour a reform to some extent, do not have such a majority in the Bundestag. The presence of a blocking minority can delay the implementation of measures, especially in the defence sector. The more one instrument is used, the less the other will be used. It will probably be easier to obtain this super majority for special funds (SF) than for an ambitious reform of the debt brake rule. The SFs are criticised for being "off-budget", but they ensure that the funds will not be used for other purposes at a later date (the Constitutional Court ruling of November 2023 guarantees this).

It is therefore likely that there will be a significant change in the fiscal stance, but this may take many months and, in any case, we should not expect a major stimulus. The choices will depend as much on external pressures as on Germany's economic situation in the coming months.

The debt brake rule can be reformed but will not be abandoned, as the CDU intends to maintain pressure on social spending. We expect a modest relaxation of this rule. The structural deficit ceiling could be raised slightly - from 0.35% of GDP to 0.5% of GDP, for instance - to increase the government's room for manoeuvre. This would allow some pro-business fiscal measures to be taken, which are unlikely to be financed by a reduction in social spending.

With regard to special funds, the envelope could be between 100 and 200 billion euros over five years. If there are any surprises, it is likely to be in the area of defence. The one unanswered question at this stage is whether the AfD, which opposes Ukraine aid, would risk opposing an SF that would increase Germany's defence capabilities.

Shortly after the start of the Russia/Ukraine war, Olaf Scholz had a special fund of €100 billion voted in to modernise the German army. This fund will soon be exhausted. The CDU's election programme was cautious but the Munich Security Conference was a game changer.

The future Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, declared that Germany should increase defence spending as a percentage of GDP, from 2% to 3%, without specifying the timeframe. To achieve this target starting in 2026, a budget of €200 billion would be needed over the next five years.

What will be the economic impact of such policies?

The process of revising the constitution and creating a new fund will take time. We therefore don’t expect to see any impact on growth before 2026. Empirical studies show that public investment typically has an average multiplier of around 0.8 in the first year, and around 1.5 within two to five years. However, defence spending has a lower multiplier in most European countries because a lot of military equipment is imported. It is worth noting that Germany's extra defence spending over the last two years (military spending rose by nearly a quarter in 2024, or 0.4% of GDP) have not been enough to pull the economy out of recession.

We expect the next coalition government will mobilise fiscal policy more proactively and that this will contribute significantly to German growth next year. However, the coalition contract negotiations will need to be monitored very closely in the coming weeks to confirm this view.

Investment Implications

Fixed Income

The two main reasons to be cautious about German debt in global fixed-income portfolios before the elections are still firmly in place. First, German government bond yields are the lowest in the euro zone and among the lowest in Europe, so more attractive valuations are on offer elsewhere. Second, Europe’s largest economy has been underperforming its peers and needs a significant fiscal boost, particularly on investment.

That will mean issuing more debt at a time when global government bond supply is already very high relative to history and central bank balance sheets are shrinking rather than growing. Given this backdrop, German yields would need to rise further if they are to become more attractive, and especially so for long-maturity bonds. While this could lead to a further steepening of the German yield curve, there is a need to remain agile on positioning at the short end.

This part of the curve will be sensitive to any inflation numbers that might challenge market expectations that the European Central Bank will cut policy interest rates by a total of 75 basis points this year. Only a sustained bout of risk aversion would prompt a re-evaluation of the appeal of German Bunds given their traditional role as a safe haven but, for the moment, there are better risk/reward opportunities on offer.

Investors may, for example, find value in carry trades that offer good visibility. Potential candidates include Italian, Spanish, and Greek bonds, and possibly Polish or Hungarian debt.

Equities

Germany’s blue-chip DAX index has had a good run over the past 12 months, outperforming other major European bourses, and even the S&P500, by delivering total returns of around 30%.

The rally came despite well-documented domestic economic challenges and was driven by stock-specific issues, the sectoral exposure within the index (40% of the index is accounted for by just four stocks), and the significant global revenue exposure of index members (80% of DAX members’ sales are generated outside Germany).

Despite this strong performance, the index remains reasonably valued, relative to both its own history and other markets, at 13.7 times forward earnings. Moreover, consensus estimates anticipate EPS growth of 11% for the DAX over the next 12 months, above the 8% expected for the broader European market, and not too far from the 13% predicted for the US market.

Valuations do not seem unduly optimistic and investors’ focus will now turn to the chances of a reform of the debt brake and the new government’s appetite to set up a special fund focused on defence, and possibly infrastructure. Its ability to deliver corporate tax cuts and ease the regulatory burden on companies will also be of interest.

Such an outcome would benefit domestically focussed companies (small and mid-cap stocks enjoy higher domestic exposure), more cyclical companies, and in particular those exposed to a potential boost to infrastructure and defence spending.

More broadly, coalition negotiations that suggest key reforms may be delivered would be positive for the wider European economy and regional equity markets.