Summary

Executive summary

| Monica DEFEND Head of Amundi Institute |

Investors should focus on currencies as a potential source of return and risk diversification for a portfolio.

What is the purpose of this paper?

In the initial papers of this series, we have addressed issues around how institutional investors should set their investment objectives, how to articulate their asset allocation across different horizons, and how to segment their investment universe. Another key issue to address in an Investment Policy Statement (IPS) relates to the hedging policy investors should adopt for their international assets, particularly:

- Should such a hedging strategy vary by asset class?

- What considerations should drive this hedging strategy?

- How active should they be in their currency management?

This paper is designed to help investors answer these questions.

What are our sources and credentials?

Our answers are based on a combination of financial literature, the findings of investor surveys and through our regular contact with institutional clients, as well as our extensive experience in advising them on asset allocation issues.

Who is this paper for?

It is directed towards institutional investors and should be particularly relevant for investment professionals involved in setting strategy or exercising management responsibilities within an investment organisation.

Key messages and recommendations:

- Investors generally decide not to hedge fully the foreign exchange (FX) exposure associated with their overseas investments, as currencies bring diversification into institutional portfolios and contribute to reducing their volatility. Currencies can also be useful tools for implementing certain macroeconomic views and for building an efficient multi-asset portfolio.

- As with other asset allocation choices, FX strategies should vary across time horizons. Whereas strategic FX allocation essentially stems from long-term risk optimisation, medium-term FX allocation is usually based on macroeconomic and valuation considerations, and tactical FX allocation may also include momentum or market-trend considerations.

- The main factors impacting investors’ strategic hedging policy are the status of their domestic currency – in most cases, a lower degree of hedging is warranted when the base currency is more volatile – and the structure of their asset allocation, as financial literature and investor practices justify higher hedging levels for risk-off than for risk-on assets such as equity.

- When investors choose to implement an active medium-term FX strategy, they should base it on well-articulated investment beliefs and define a process and governance consistent with those beliefs.

- Tactical FX strategy is also applied by some investors, but it requires significant resources in terms of investment expertise and quality of systems.

To hedge or not to hedge?

As the overall investment environment remains uncertain and the attractiveness of major asset classes is challenged, we believe it is appropriate to focus on currencies as a potential source of return and risk diversification for a portfolio. Indeed, FX has a number of advantages as an asset class. It is highly liquid, at least in the case of the main global currencies, and accessing currency markets is less costly than accessing other asset markets due to the huge volume of daily currency transactions. Moreover, currencies do not carry duration or issuer risk – although admittedly counterparty risk cannot be fully discarded – and can be a useful source of diversification for a portfolio.

Despite these advantages, managing FX is a source of complexity for many investors who sometimes consider the FX exposure linked to their overseas investments as an unwelcome source of risk and are not sure how to manage it. Currencies can indeed be volatile and are difficult to forecast, and they do not offer a systematic premium to be reaped, unlike other asset classes. As argued in a previous paper, we believe that asset allocation decisions respond to different goals and are articulated around different approaches, depending on their horizon. This also applies to FX decisions. As such, we suggest addressing the issue of FX hedging via strategic, medium-term, and tactical horizons, based on academic literature and institutional practice, as well as our own experience as multi-asset managers.

Currency in strategic asset allocation

According to financial literature, it is appropriate for investors to not fully hedge the implied currency exposure of an internationally diversified portfolio. What share of assets should they choose to hedge or keep unhedged? In a seminal paper, Fischer and Black argued for a “universal hedge ratio”, defined as a “constant related to an average of world market risk premia, an average of world market volatilities, and an average of exchange rate volatilities, where we take the averages over all investors”. Reality is more complex and there seems to be a large variety of investor attitudes in terms of foreign asset hedging policy. In an older paper which is still considered a useful reference, Sebastien Michenaud and Bruno Solnik observed that a broad range of strategies – from systematic to no currency hedging policy and with some investors applying a ‘minimum regret hedging policy’ – feature 50% hedging. More precisely, the institutional practice usually consists of applying a different hedging ratio depending on asset classes: the largest part of non-domestic fixed income, sometimes up to 100%, is generally hedged, whereas equity hedging is more limited and is often derived from an asset allocation optimisation analysis taking into account the overall portfolio structure.

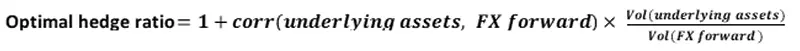

Investors in developing countries also tend to consider FX as a means of protection against domestic inflation, especially when they cannot rely on a domestic inflation-linked assets market for that purpose. FX can also reduce portfolio risk, as it provides diversification against other asset classes, especially equities, due to the low -- or sometimes negative -- correlation between equities and currencies, whereas this is less the case for fixed-income assets. For instance, the return of the Japanese equity market has historically been negatively correlated with the exchange rate of the yen against other major currencies, even though this link has not been so clear recently. Mathematically, the ‘optimal’ hedge ratio – or the hedge ratio that minimises the volatility of the overall portfolio, taking into account underlying assets and FX instruments used for hedging purposes -- is determined by the following mathematical formula:

In other words, if the portfolio of underlying assets is negatively correlated to the currency forward, it is optimal for the investor to hold some foreign currency exposure, as it can reduce the overall portfolio risk, whereas a high hedge ratio is recommended if the correlation is positive. Let us illustrate this through an analysis of the two major factors that should help define the level of FX hedging in strategic allocation: the features of the investor’s currency and the structure of its portfolio allocation.

Features of an investor’s domestic currency

If the domestic currency is highly sensitive to the global economic cycle, domestic assets will suffer during periods of market turmoil and economic downturn, and unhedged exposure to foreign assets will offer useful portfolio protection. For example, according to a large Australian investor, foreign currency exposure gives “access to defensive currencies that provide returns and liquidity in times of market stress and protects purchasing power when the Australian dollar weakens”. Our Canadian pension fund clients also tend not to strategically hedge their exposure to US assets, as they see the US dollar as a safe-haven currency that offers useful tail-risk hedging features against their domestic currency whose behaviour is partly driven by trends in commodity prices and more generally by market risk appetite.

The view that FX, through exposure to core currencies, is a potential source of portfolio tail risk mitigation is also shared by a number of Nordic or Asian institutions, whose domestic currency is positively influenced by global cyclical conditions. Meanwhile, pension funds in Switzerland, or Japan – where the home currency can act as a safe haven in times of market turmoil – display opposite features. US- and euro-based investors, who enjoy highly liquid and core domestic currencies, have more incentive to hedge their foreign assets exposure (see box 2). Usually, the dollar has proven to be a better hedge than the euro.

Impact of a portfolio’s asset allocation structure

In the case of a strategic allocation with modest expected return and risk, heavily dominated by fixed-income assets, optimal FX hedging will often be close to 100%, as the additional risk contribution of FX cannot be offset by its diversification benefits. On the other hand, strategic currency hedging will be very limited in the case of a high-risk portfolio with a heavy content of risky assets, as the benefits of diversification will then be tangible. This confirms that different approaches are recommended for hedging fixed income and equities.

A strategic hedging policy to be applied to real and alternative assets is a more challenging issue, as these assets feature specific complexities which are particularly linked to valuation uncertainty and a lack of data frequency due to their limited liquidity. As the exact underlying FX exposure is often difficult to assess, some institutions prefer not to hedge it at all for these assets, whereas others aim to hedge all alternatives, albeit imperfectly. Reflecting the different hedging approaches for equity and fixed income, some Canadian pension funds strive to hedge infrastructure and real estate, as their risk level can be seen to be closer to fixed-income risk. Hedging strategy also depends on the weight of alternative assets in a portfolio, as it may not be worth looking for a solution to this complex problem if these assets are only marginal.

Hedging costs and liquidity are other factors that influence the hedging policies for different asset classes. Most investors consider that hedging emerging assets in particular is too complex and expensive. Some large institutional investors also prefer not to hedge their exposure to currencies with limited liquidity, such as Norwegian krone, Danish krone or New Zealand dollar. In addition, investors should not confuse the assets’ currency denomination with their currency exposure. For instance, regulation had to be changed in Chile after the 2008 crisis, as prior to that, exposure to a Brazilian equity fund denominated in US dollars, for instance, was considered as a dollar risk which was an inappropriate reflection of the true underlying risk.

To illustrate the influence of an investor’s currency base and asset allocation structure, we present two investor cases in the following boxes. The first applies to an Asian pension fund in an export-orientated country, whose currency may suffer against the dollar during periods of market stress. The second refers to a euro-based pension fund with a conservative asset allocation structure.

Box 1: Emerging Asian pension fund

The investor’s reference allocation is 70% hedging assets (fixed income), 20% growth assets (essentially equities), and 10% inflation-sensitive assets (real estate and infrastructure). Exposure to domestic asset classes, which is about 75% of the reference portfolio, is obviously 100% denominated in the domestic currency, whereas this is not, or very limited, the situation for the allocation to international assets. Table 2 quantifies the impact of hedging the return and risk of all asset classes included in the investor portfolio (please note that these impacts are specific to this investor’s currency and should not be taken as absolute conclusions). Hedging global bonds significantly reduces their volatility, as expected, but also improves returns from this investor’s standpoint. Meanwhile, hedging gold increases the return marginally, but meaningfully increases the volatility. The benefits of diversification between gold and the exchange rate of the investor’s currency against the dollar are then lost.

Moving to a portfolio level analysis, we conducted an optimisation of the hedging ratio by mixing hedged and unhedged allocations. The efficient frontier represents the risk-return profiles of all combinations of hedged and unhedged allocations. The minimum risk corresponds to the fully unhedged allocation (see the red triangle at the lower left-hand corner of figure 1). This shows that, despite the volatility reduction induced by hedging at an individual asset-class level, the risk-return trade-off is often more favourable to unhedged portfolios due to the impact of correlations, suggesting unhedged currency exposure diversifies and reduces portfolio risk, with only a very slight negative fallout for returns.

Box 2: European pension fund

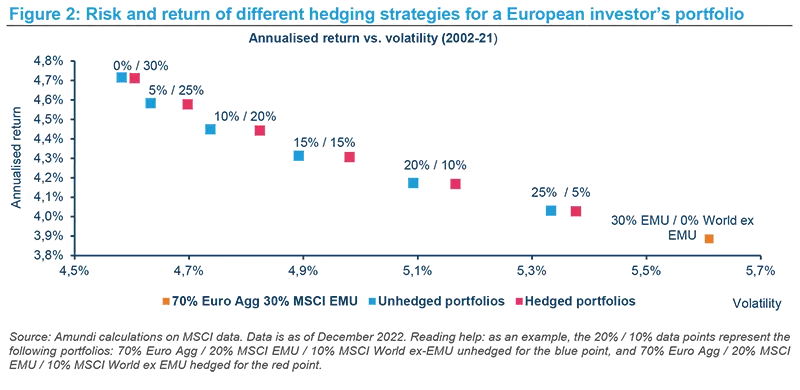

Now we turn to the example of a European pension fund with a 70% fixed income and 30% equity strategic allocation and apply a simpler methodology than used in box 1, essentially based on historical data. We assume that fixed income is invested domestically, with the Euro Global Aggregate Index as a reference. We start with a purely domestic equity exposure and introduce international equities, represented by the MSCI World Index, replacing Eurozone equities, by tranches of 5%. In the first simulation, all international equities remain unhedged (blue points in the chart), while in the second one they are fully hedged (red points in the graph). Figure 2 compares the two simulations.

In this example, there is no clear advantage for one strategy against the other in terms of return and the main benefit in return-risk terms is linked to the partial rebalancing from Eurozone to global equity rather than being linked to the currency component. In terms of risk, the unhedged strategy has a slight advantage over the hedged one during the 20-year period of analysis. This benefit, in terms of lower volatility, reaches its peak of about 10bp (4.89% vs. 4.98% volatility) for an equity component equally split between euro and non-euro equity (15% weight for each). It is modest and varies over time, and was particularly pronounced during the period of high market stress around the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the euro debt crisis, which saw a succession of weakening and strengthening periods for the dollar-euro exchange rate. This example would tend to confirm that keeping part of an international equity portfolio unhedged allows investors to benefit from an intrinsic diversification effect between equities and FX, although the advantage in this case is limited. As multi-asset investors, our experience – taking the example of a euro-based 50% global equity / 50% domestic bonds portfolio – is to keep about 20% of the portfolio unhedged. Given the weight of euro markets in global equity indices, this corresponds roughly to a 50% FX strategic hedge of the foreign equity exposure and a full FX strategic hedge of the foreign bond exposure, notwithstanding the possibility to tactically manage currency hedging.

Medium-term allocation: active or passive?

Once they have set their strategic FX allocation, investors may amend it within a medium-term horizon, by implementing an active currency strategy. This consists of diverging from the hedge ratio set for the SAA, while a passive strategy is designed to bring systematically the portfolio’s hedge ratio back to the SAA or reference portfolio. Active currency decisions can themselves respond to different objectives, for example helping to manage the overall portfolio risk or improve its expected return by aiming to benefit from a given macroeconomic or valuation view.

The choice of being active or passive regarding currency management hinges critically on the investor’s belief. For some, currencies are too difficult to forecast and are a transaction tool rather than a ‘buy-and-hold’ asset. They may also consider that an active FX approach requires an excessive amount of effort and resource in terms of research, investment, execution, risk management, performance measurement and reporting, whereas the expected reward is limited in the absence of a premium or embedded return, as is the case for bonds and equities. FX should then essentially be considered for its risk diversification properties, helping minimise portfolio risk. For instance, according to Swedish pension fund AP4, an open currency position is mainly relevant from “a risk mitigation perspective, where the level is regulated primarily through currency forward contracts”.1

For other investors, global portfolios have a natural FX exposure, which can significantly impact their return and risk and should be managed professionally. As explained in a recent AP3’s annual report, “Currency management is one of the fund’s most important areas to manage risk and generate returns”. Some investors in this group may point to long-lasting trends in currency markets that they would want to take advantage of. Unlike bonds and equities, which have idiosyncratic features linked to the company or the issuer, currencies are essentially driven by macroeconomic considerations, making currency forecasting appropriate for investors with a top-down investment approach. Nevertheless, the passive approach appears to be the most common among institutions, but in order to be implemented rigorously, it requires that the investor has a look-through for all underlying positions, which is not necessarily an easy task.

Medium-term currency decisions mainly require the expression of a limited number of currency views that result from:

- Macroeconomic views: sound macroeconomic fundamentals are associated with currency strength. Currencies may also help build a portfolio to suit certain macroeconomic scenarios, for instance, using commodity currencies in a scenario of rising commodities, export-oriented, emerging currencies to benefit from a scenario of accelerating global growth, or safe-haven currencies such as dollar, Japanese yen, or Swiss franc in the context of rising risk aversion across financial markets. The capacity of FX to replicate these macroeconomic drivers depends on whether they are good proxies for these drivers. For example, in our multi-asset portfolios we have used Australian dollar-Japanese yen as a good indicator of risk on/risk off market conditions, but this relationship has not worked well in the very recent period as a result of the Ukraine war and its impact on oil markets. Investors should also keep in mind that the impact of macroeconomic variables on FX varies over time. We have seen market participants focus sequentially on trade balance, money supply, interest-rate differentials or inflation as key influences in FX.

- Valuation: it is typically based on models such as a simple purchase-power parity (PPP) or a combination of different valuation models, such as Behavioural Equilibrium Exchange Rate (BEER) or real effective exchange rate (REER). Academic work underlines interest rate differentials such as carry trades, for instance, which involves benefiting from the higher interest rates offered by foreign fixed-income securities against domestic fixed-income securities, as a source of investors’ speculative demand for active FX strategies. Some investors may amend their strategic hedging policy if they believe that their domestic currency is strongly over- or undervalued. As an illustration of medium-term valuation considerations influencing an investor’s hedging strategy, a Canadian pension fund reported to us that it decided to unhedge most of its exposure to US assets in 2015, at a time when they thought that the Canadian dollar was very overvalued against the US dollar. Such a strategy implies a certain stability in the long-term relationship between two currencies, as structural changes in a given country can justify a major adjustment of its currency’s status.

According to our observations, these medium-term currency strategies can be subject to a relatively broad leeway. For instance, if the international equity allocation of a portfolio is defined as 50% hedged in SAA, actual hedging of that share can be set within a 30-70% range for the medium-term asset allocation (MTAA). In this case, investors should make sure that reaching the extreme positions in the allowed range does not lead the portfolio risk to rise significantly versus the SAA risk.

Some institutions have also defined systematic rules to decide on the size of their active FX strategy. As an illustration, one of our large institutional clients uses deviations from a fair valuation level, estimated using a PPP model, as the threshold for trades to be implemented. For instance, if the dollar – as the most important foreign currency for this investor – is overvalued by one standard deviation according to the model, the hedge ratio of dollar-denominated assets is increased by X% in the MTAA. For two standard deviations, the hedge ratio will be increased by Y%.

1 Source: public information from A4.

Box 3: FX hedging strategies - a case study

Currency is a core asset class for asset managers. The 24-hour FX market is highly liquid and generally reacts quickly to market developments. It, therefore, provides a huge variety of options for hedging client portfolios and reducing embedded volatility. There are several different approaches to this asset class:

- An active and absolute-return approach seeks to make the most of macroeconomic and fiscal policies, as well as technical discrepancies. With a global macroeconomic approach, utilising robust portfolio construction tools, investors can implement lowly-correlated strategies which aim to play macroeconomic themes such as global or regional recoveries, pro-cyclical currencies and geopolitical tensions.

- Overlays are designed and implemented with targeted levels of FX exposure and calibrated hedging strategies:

- Active currency overlay: this strategy uses currencies as an asset class to enhance global portfolio returns. Currencies are rebalanced continuously in favour of those with a better risk-return profile, while applying a predefined risk budget.

- Dynamic currency overlay (DCO): this strategy designs an optimal hedge ratio reflecting the investor’s goal of reducing global portfolio volatility. The optimal hedge ratio is adjusted over time to limit underlying asset volatility.

- Passive currency overlay: this strategy defines a specific level of FX exposure in order to reduce the portfolio’s currency risk.

Here is an example of a DCO. A large European institutional investor is willing to diversify its euro-denominated fixed-income allocation by allocating to dollar-denominated US Treasuries through a DCO. This entails a three-step process:

- Determination of the optimal hedge ratio: currently, it stands at 83% given the negative correlation between US Treasuries and the USDEUR cross-exchange rate;

- Current dollar valuation looks expensive in purchasing-power-parity (PPP) terms, as it is more than one standard deviation above average, adding a further 10% to the hedge;

- Tactical positioning: tactically, the portfolio managers opt to buy 3% of additional dollar exposure.

In the end, the overall hedge programme represents 90% of dollar exposure, keeping a 10% USDEUR position open.

Tactical FX allocation requires significant resources

For some investors, active FX management also includes a tactical component, orientated towards the short term, typically less than one year. In this case, it is mainly focused on generating excess return over the MTAA. When allowed, tactical currency decisions are typically more numerous, smaller in size and often based on momentum and technical grounds, requiring constant market awareness and portfolio monitoring. As a result, they should be made under the remit of currency specialists who have experience in understanding the short-term drivers of currency markets. Likewise, an investor with a core and stable home currency expecting an increase in market volatility may choose to increase its FX hedging.

Currency management requires a professional analysis of the currency drivers included in an investor’s universe. Such expertise cannot be developed for all currencies. Investors should therefore be selective. Given the weight of US and, to a lesser extent, European markets within global indices, the dollar and the euro will naturally be included in the universe. For many investors, the main allocation decision will relate to the exposure of the dollar against their domestic currency, due to its major impact on the portfolio return, which has been further strengthened by the increased weight of US markets in international benchmarks reflecting the flow into US-based global technology leaders. Other currencies may be included if they can provide proxies for macroeconomic drivers. Energy-related currencies, such as Norwegian krone or Canadian dollar, may be used as inflation-linked assets. Investors in an emerging country may also feel comfortable with managing the currencies of their neighbouring countries, even though geographical proximity is not necessarily an advantage in FX markets.

Hence currencies may be segmented into relatively homogeneous blocs, which can be defined along geographies or macroeconomic drivers, or a combination of both in a matrix mode. The following segmentation is an illustration of this approach:

- a dollar bloc, including Canadian dollar and emerging currencies tightly linked to the dollar;

- a euro bloc, including Swiss franc, British pound, Nordic and Eastern European currencies along with the euro;

- a Japanese yen bloc, limited to the Japanese currency due to its highly idiosyncratic behaviour;

- an Asian bloc, around the Chinese yuan; and

- an emerging commodity currencies bloc, including Russian rouble, South Africa rand and Colombia peso, for instance.

First, investors can choose to allocate their portfolio between different currency blocs and, as a second step, within each bloc. However investors should regularly check the validity of this segmentation, as currencies’ status may evolve over time and depending on market circumstances.

Portfolio weighting rules, to be applied to the major currencies in the portfolio, should also be clearly defined under the condition that liquid derivatives instruments are available for easy hedging or to gain exposure. They can take the form of an overall ex-ante risk budget, a maximum currency deviation against the strategic benchmark or stop-loss rules to quantify the maximum loss that an investor can bear if its expectations are not fulfilled. More specifically, based on our experience, currency allocation budgeting should depend on the expected return that FX specialists are realistically able to achieve, and particularly on:

- their target information ratio;

- their hit ratio (share of winning versus losing positions);

- the win/loss ratio (size of the average winning versus average losing position); and

- the number of transactions in active FX.

Box 4: Active currency management, example of Amundi’s multi-asset strategies

Currencies are an important part of our four-pillar multi-asset process. Portfolio managers actively manage currency risk on a tactical basis, potentially leading to some short-term differences with the currency weights included in the medium-term asset allocation. Our currency decisions tend to be segmented along the key pillars featuring our investment approach:

- Currencies can be used within the macroeconomic pillar featured by our view of the world. For instance, a bullish view on the global macroeconomic cycle may be implemented via an exposure to pro-cyclical currencies, such as emerging ones. In the first asset allocation level, we typically use G8 currencies which are very liquid, as well as the main emerging currencies, for instance to play a recovery in the global macroeconomic cycle.

- Currencies may also be used within our hedging pillar, as we do not want all strategies included in a portfolio to be in line with our central scenario. For instance, commodity currencies may be included in an asset allocation bucket designed to protect a portfolio against the risk of an inflationary scenario. We may also choose to invest in risk-off currencies, such as Swiss franc or Japanese yen, if we want to increase the portfolio’s resilience to an anticipated market stress event.

- Currency strategies may also be included in our satellite pillar as an additional asset allocation layer, with long-short tactical positions based on valuation gaps or on macroeconomic anticipations. Typically, such strategies will be implemented within the same currency bloc, such as Norwegian krone-Swedish krona or New Zealand dollar-Australian dollar.

The authors would like to thank Marie Brière, Viviana Gisimundo, and Kokou Topeglo for their contributions, as well as Jean-Xavier Bourre, Benjamin Bruder, Shane McDonald, Antonio Motta, Bertrand Paquot, Cosimo Marasciulo, and Francesco Sandrini for their careful reading and useful comments.