Summary

The many challenges that lie ahead will likely lead to high volatility in the global cycle, in terms of growth and inflation. To weather such an uncertain period a more dynamic asset allocation framework is needed.

Executive summary

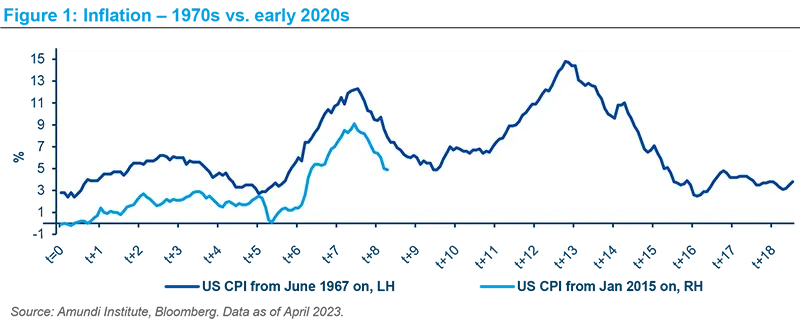

Our view, reinforced by the Covid crisis and the Russia-Ukraine war, that the 2020s could bear similarities with the 1970s, has gained more traction since 2021, primarily due to high inflation.

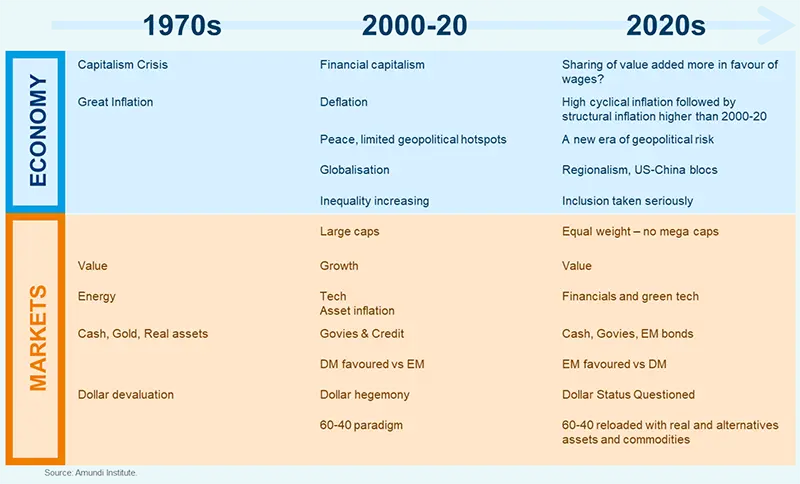

While the 1970s were followed by structural economic changes that included triumph of supply-side economics, globalisation and a shift of value added in favour of capital, there is now a widely shared narrative that incoming transformations will go the opposite way.

Despite near-term worries, inflation remains less persistent than during the early 1970s. From a cyclical point of view, it is likely to return more easily to levels closer to targets, especially because monetary policy has been more decisive.

Longer term, while arguments in favour of a change in macroeconomic regime abound, both inflation and growth are likely to be caught in a tug-of-war between opposite forces. There is still uncertainty on the end game, but we expect high volatility in the global cycle, regarding growth and inflation, due to the challenges that lie ahead, like the energy transition and the road to net zero, and some forces in Developed Economies to gain more strategic independence.

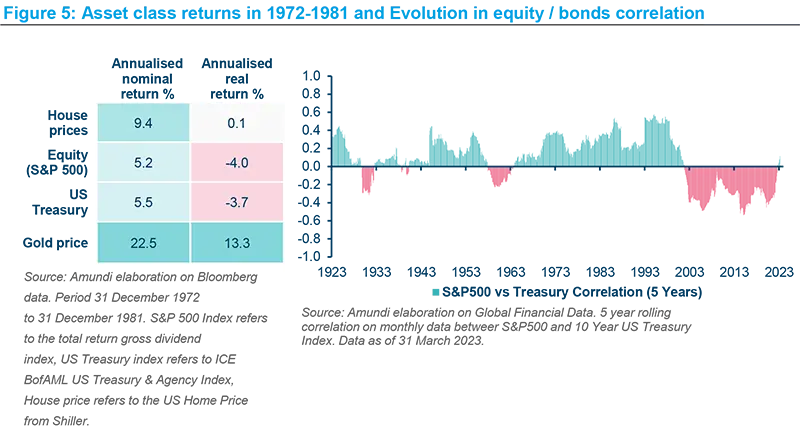

Investment implications include more diversification in terms of asset classes (due to more frequent expected co-movement of bonds and stocks, and lower expected Return on Equity - ROEs), more regional diversification and the need to develop a dynamic asset allocation framework able to capture the swing in growth and inflation dynamics with an horizon of 1-3 years.

A regime shift vs the past decade, still including some 70s features

Are the 2020s like the 1970s?

Even before the current decade began, and before Covid and the Ukraine war, we believed the 2020s would bear similarities to the 1970s. What happened in the last years has obviously reinforced this conviction. These events begin with the sharp surge in inflation, combined with fledgling economic growth (stagflation) since 2021. They also extend to some of the certain and presumed causes of this stagflation:

- A war generating a surge in energy prices (Ukraine like Kippur) as a short-term trigger.

- The lagged effect of monetary and/or fiscal profligacy (post-Lehman QE and Covid policies like a series of pre-70 policies to address the financing of the Vietnam war, Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society or the post-war reconstruction) as a long term cause.

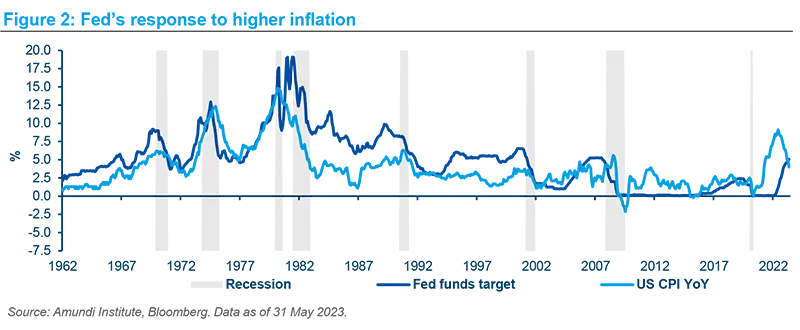

Inflation and monetary policy in the 1970s and their consequences for the real economy.

What followed from the early 1970s on was a decade of volatile and sometimes very high inflation (with two spikes, in late 1974 and early 1980), only tamed at the price of a complete revamp of the monetary policy framework, ultra-high interest rates and a sharp recession (at least in the US). Regarding the output, the 1970s also paved the way for a paradigm change for supply-side economics (implemented from the 1980s on, after it won the academic debate in the 1970s), deregulation, offshoring, the triumph of the so-called “shareholder capitalism”, and several decades of deindustrialisation that deeply disoriented the Western lower and middle class. These changes were accompanied by a shift in the sharing of value added away from wages, and towards capital both companies and housing.

In light of this experience, today’s burning questions are:

- whether bringing down today’s high inflation needs to be as painful as it was then, and, if so whether Central Banks will show the required determination;

- whether we should expect another paradigm change in the global economy.

Nonetheless, the two scenarios are not identical

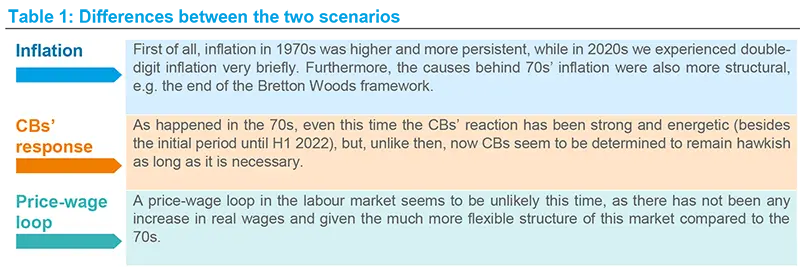

Despite the many similarities between the two periods, some crucial differences explain the reasons why this time the final outcome, in terms of economic consequences, could be different.

Regarding the short term, there are many differences between today’s inflation and that seen in the 1970s, which lead us to believe price pressures may abate more quickly this time.

- First, inflation has not been as high as in the early 1970s, at least so far, largely owing to Central Banks’ decisive action and wariness of second-round effects. Double-digit inflation has remained a rarity, avoided particularly by the US, and only very briefly experienced by the euro area and other countries.

- Furthermore, causes of high inflation are different. With regard to this, it is essential to recall that the high inflation of the 1970s also followed the exceptional monetary event that was the end of the fixed peg of USD to gold and therefore demise of the Bretton Woods framework. In other words, the very nature of the common numeraire of the global financial system changed (from gold-based to fiat), logically leading to a large swing in its real value. There has not been, recently, a similar referential-changing event. Nowadays, the topic of the USD's global status has risen since some countries have been diversifying reserves away from the USD (for instance as a risk management decision), particularly as some trades have been settled in currencies other than the dollar (e.g. India-Russia for oil), although such examples have been limited.

- Central Banks’ reaction to inflation has been strong after an initial slow start. We could argue that the rate hike at the beginning of the 1970s was also very sharp, at least in the US. Yet, this time, thanks to lessons from the past, Central Banks are unlikely to cut rates as quickly as they did then, and seem to intend to remain on the hawkish side as long as economic conditions make it bearable.

Even more so, long-term inflation expectations have only slightly moved upwards, signalling that Central Banks’ credibility on inflation is not at risk. Indeed, inflation expectations are a conventional indicator of Central Banks’ reliability, yet also influenced by experience of past inflation episodes. In other words, a combination of rational and adaptive expectations. Current economic participants do retain the memory of decades of disinflation. According to basic macroeconomic theory, anchored inflation expectations should help inflation move lower and prevent the initial supply shocks from morphing into a prolonged price-wage feedback loop. Little of this existed in the 1970s, where, while short-term memories were of relatively low inflation, Central Banks had not built specific credibility in this regard (as they tended to pursue and communicate on multiple macroeconomic and financial goals).

- Regarding the labour market, conclusions of a price-wage feedback loop are premature, as wage increases have fallen short of inflation yet (i.e. there has been no increase in real wages). Note that the much more flexible structure of the labour market compared to the 1970s’ (much less inflation indexation and, overall, less powerful trade unions) also makes this type of loop less likely.

Bearing these factors into account, a 2nd spike in inflation (similar to that of the end-1970s) is unlikely. At the same time, for Central Banks, bringing inflation back to their targets may not require a deep recession.

Note, though, that the caveat here can be that the second spike in inflation in the late 1970s was accelerated by the 2nd oil shock (post-1979 Iranian revolution). Another large geopolitically driven energy supply shock in the coming quarters or years cannot be ruled out and it is a risk to watch.

A tug-of-war between opposite forces

Retreat of globalization, and inflation as its expected consequence, are all but sure. Indeed, a slowdown in growth seems to be a more likely effect and, moreover, technological developments seem to be deepening globalisation within services activities.

However, even though markets can expect inflation to be less persistent than in the 1970s in terms of magnitude and duration, they must also mind that it could nonetheless trigger more financial, as well as macroeconomic, volatility.

This is largely due to much higher leverage than the 1970s’, be it in the public or private (household and corporate) sectors. First, high debt levels mean that governments will be more constrained in how they can respond to economic shocks. Then, debt-related public or private financial accidents cannot be ruled out as a lagged effect of the rise in rates of the past 18 month. Moreover, valuations of assets have sharply readjusted (in the case of bonds), or may still have to do so following the higher rates (i.e. some illiquid assets). Although the situation appears far less risky than in the pre-Lehman era, we can still see the risk of some shockwaves (through various channels) from assets markets to the general economy. Low market liquidity may amplify them.

- On inflation, while globalisation has often been identified as a key cause of the lowflation of the last decades, its predicted reversal is logically seen as carrying the opposite effect. It is, however, not so clear whether that will be the case. First, even if considered a prolonged and gradual negative supply shock, deglobalisation may be more growth-negative than inflation-positive. Moreover, how deglobalisation will proceed (if at all) remains in question: it is often seen as taking shape largely through the reshoring of manufacturing activities, accelerated by deliberate reindustrialization policies. However, goods are now a much smaller share than services in inflation baskets, with new technologies potentially opening the way for a deepening of globalisation (i.e. international fragmentation of value chains) within services activities.

Other factors often mentioned as inflationary over the long term include expected large investment plans for such goals as sovereignty/strategic autonomy in key sectors, climate change, or the reduction in social inequalities. However, to what extent these changes are structurally inflationary will largely depend on how they will be financed: whether Central Banks accompany them with long-lasting accommodation or whether they will be financed by tax increases.

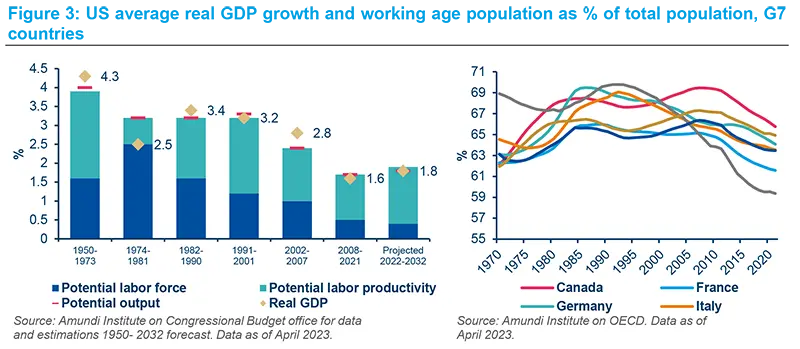

- When it comes to economic growth, higher appetite for investment may be a clear positive. On paper at least, this is the ideal vector of higher demand and productivity growth at the same time. However, investment plans could well fall short of ambitions if bogged down in conflicting priorities, red tape and resistance from vested interests. Moreover, some forces of secular stagnation are still here, such as the factors behind declining productivity growth (ageing and the transition from manufacturing to services) or the falling growth in the working age population. Negative factors may even be supplemented by more frequent and intense episodes of climate change and geopolitical disruption that hurt growth.

- In terms of the sharing of value added, opposite factors are also at play. On the one hand, policies aimed at calming fatigue towards supply-side economy and the rise in non-conventional political forces may lead to a rebalancing of value added towards wages (with uncertain implications on growth speed). On the other hand, accelerating new technologies, while benefitting a minority, could make the majority of workers even less marginally productive and shift further the value added in favour of capital.

Nonetheless, as of today, likely features of the new regime are: mild higher structural inflation (this could mean CBs simply reaching their targets, instead of the frequent 2000-20 undershoots), some gradual extension of de-globalisation, growth rates similar to the previous decade, a slightly higher share of the pie towards wages at the expense of capital.

New tools to navigate a more uncertain environment

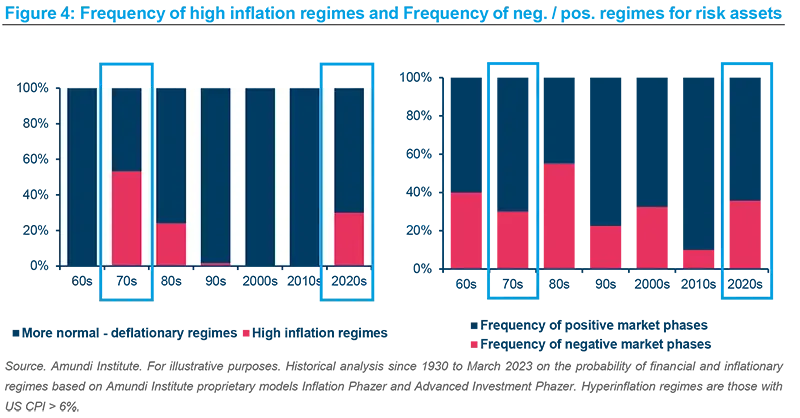

Investors should be aware that adjustments towards a new regime will not be linear. The resurgence inflation episodes in the 1970s and more recently in the 2020s triggered frequent episodes of negative risk assets performance, as we can see in the chart below.

Importantly, investors will need an investment framework able to capture higher volatility in growth and inflation and adapt asset allocation decision on different regimes.

It will be important in our view to enhance diversification:

- Short term, the risk of a reacceleration in inflation is moderate, but volatility of inflation figures will likely remain high as multiple adjustments occur. From a growth and income perspective, our cyclical view remains cautious. We see some cracks in the real economy due to tighter financial conditions (commercial real estate and highly leveraged companies), while equity markets are too buoyant. Therefore, we remain cautious on risk assets. This dynamic asset allocation approach, that detects inflation points in the cycle, would help to re-adjust the portfolio, and turn more constructive on risk assets.

- Over the longer term, slightly higher structural inflation (vs. 2000-20) means more frequent co- movement between bonds and equities (through the common expected inflation part of the discount factor), something already illustrated in a spectacular way in 2022 (the worst year for a balanced portfolio since 1974, according to some metrics). Investors should therefore seek diversification beyond these two asset classes, recalling that in the 1970s most asset classes delivered negative real rates, with the exception of commodities like gold and oil.

A retreat of globalization or regionalisation, even limited, are likely to lead to less synchronized economic cycles and monetary policies across major economic regions, and thus more value for regional and currency diversification. Moreover, continuing EM growth outperformance, combined with less recycling of EM current surpluses on DM markets (the capital market side of de-globalisation), could lead to EM assets outperformance vs. DM.

Due to a possible rebalancing towards wages, margins are likely to represent a smaller share of value added, at least in DM. Investors should thus not expect the same ROEs on DM equities with an equivalent level of risk. With a longer-term view, and adding the consequences of the energy transition (different impact on growth depending on the countries), to achieve the same returns as in the past decades, investors should include real, alternative and EM assets.