Summary

- The West’s recent decision to send battle tanks to Ukraine to counteract a renewed Russian offensive increases the risk of a direct escalation with the West, while the likelihood of a protracted war remains somewhat higher. At the same time, most modern conflicts end in negotiations when both sides are sufficiently exhausted, and we consider the possibility of a ceasefire towards the end of 2023 and heading into 2024 is currently underappreciated.

- Notwithstanding how the conflict will play out, the geopolitical landscape has changed significantly since the start of the conflict. NATO has re-established itself at the forefront of Western defence, and defence spending has increased across the board. At the same time, countries that have refused to condemn Russia are enjoying newfound leverage on the geopolitical stage.

- The economic impact on Ukraine has been devastating, with over 5 million people displaced and a collapse in GDP. Estimates of reconstruction costs range from USD 350-750 billion and are still rising. So far, the Russian economy has fared better than many economists expected, mainly due to the windfall gains from last year’s spike in energy prices, but the adverse effects of sanctions will show over time.

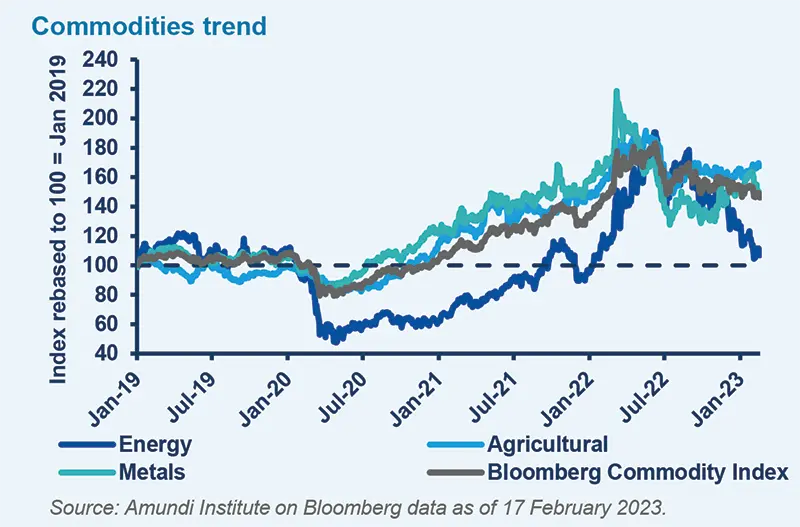

- Europe has mainly suffered from the energy supply shock, particularly the fivefold increase in gas prices. While fiscal measures have temporarily been able to dampen the effect on households and firms, finding new suppliers and diversifying the sources of energy will be crucial to preserving the international competitiveness of European industries in our view. More volatile energy and commodity prices will require a more proactive and data-driven monetary policy to contain inflation pressures.

- Emerging markets and low-income countries have suffered a much higher increase in inflation because of the higher weight of energy, commodity and food prices in their consumer price indices. Overall, greater fragmentation stemming from the war is a serious setback to globalisation and will incentivise investors to focus on country specifics rather than EM as an asset class.

- Investors have to face up to a new geopolitical equilibrium characterised by shorter value chains, greater protectionism and higher inflation. In this complicated environment, commodities can be appealing. The impact on equities, particularly in Europe, has varied across sectors and companies. This reinforces the case for bottom-up stock picking.

Geopolitics: The best and worst scenarios are underpriced

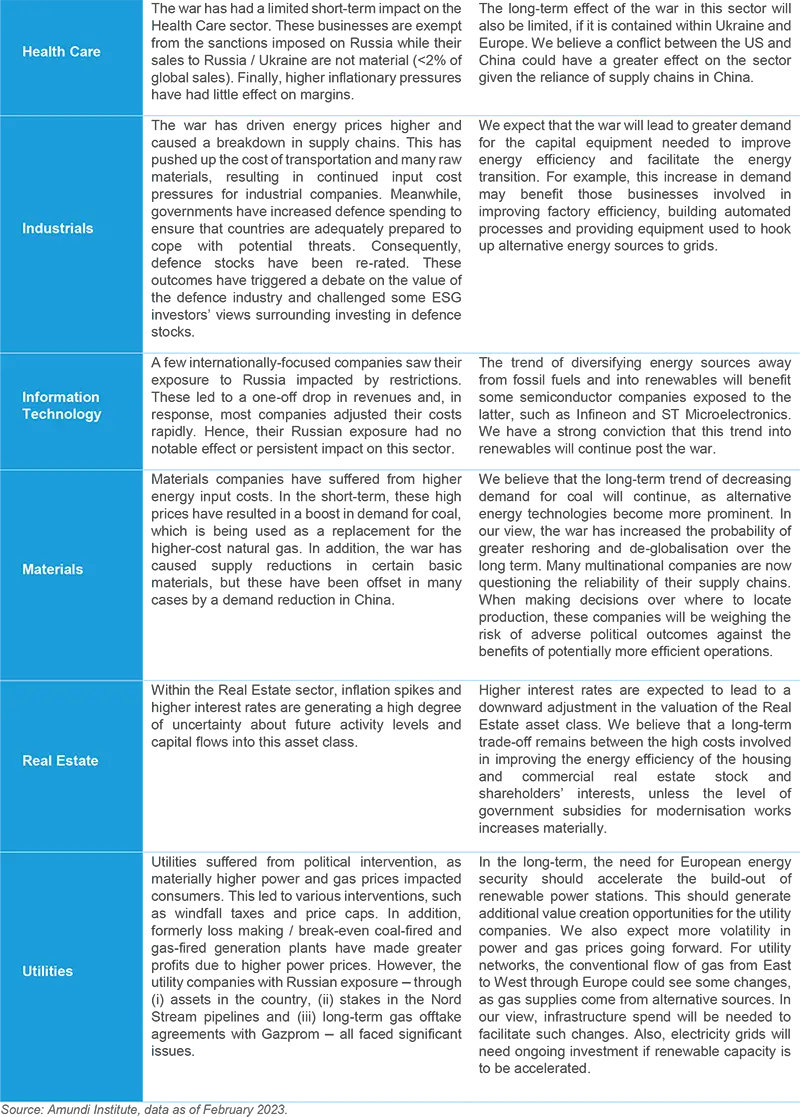

As the battle intensifies, with a new Russian offensive underway, it is unlikely that either side will decisively gain the upper hand in the near term (4-6 months). Instead, we believe two scenarios are equally likely to play out.

The first is the prospect of a long war. Russia’s large-scale military mobilisation and tactics are reinforcing its commitment to wearing down Ukrainian forces, and the public discourse in Russia is dominated by its military successes and losses rather than the question of the war itself. At the same time, Western support for Ukraine will continue in the coming months. As the West becomes progressively more disconnected from Russia, the economic incentive for peace will wane.

The second scenario is a ceasefire. A window for this scenario to materialise will most likely open towards the end of this year at the earliest. The prospect for a ceasefire has been somewhat weakened by the joint Western decision to send battle tanks to Ukraine but remains underappreciated in our view. While the timeline may extend into 2024, most modern conflicts end in negotiations, once both sides are sufficiently exhausted. There are many arguments in favour of this scenario: concerns over a nuclear escalation imply Western leaders will be keen to cap the extent of Russia’s military setbacks. Additionally, the extent and continuation of public Western support will very much depend on the socio-economic backdrop. The pain of higher interest rates and prices will still hit consumers and increase the overall level of dissatisfaction with politicians, who will be keen to see an end to the war and increase pressure for negotiations.

A third possibility is a direct escalation with the West, which in our view is also underappreciated, and merits some preparation on likely market reactions (for example in the case of an asymmetric attack on a country neighbouring Ukraine). New weapons deliveries to Ukraine increase Russia’s vulnerability on the battlefield and thereby the threat of escalation. Furthermore, while Western forces remain divided over the extent of support they should offer, more ‘hawkish’ countries are setting the tone and agenda, forcing more cautious countries to follow suit. For example, the UK’s decision to send battle tanks increased public pressure on Germany to do the same.

Despite the new weapons supplied to Ukraine, we do not believe the balance of power has shifted significantly in Ukraine’s favour. The ‘drip-feed’ approach of Western tanks and other weapons gives Ukraine mainly defensive capabilities rather than significant capabilities to push back, and is counterbalanced by Russia’s more abundant manpower. Consequently, our latest forecasts have not raised the possibility of a Ukrainian ‘victory’.

Apart from the evolution of the conflict in Ukraine, the geopolitical landscape has changed significantly in the last year.

- NATO has re-established itself as the West’s foremost defence organisation and is expanding as a direct consequence of the conflict, as shown by Sweden and Finland’s recent efforts to join. While some in the EU, particularly France, wanted to create a stronger, less US-dependent European security framework (dubbed ‘strategic autonomy’), no significant advancements have been made on this front. Instead, the US has doubled down as Europe’s main security provider, tying the continent more closely to its foreign policy goals.

- Germany is no longer sitting on the sidelines when it comes to military decision-making. It is now one of the biggest defence spenders in Europe and will remain a key player in shaping how the war progresses, but from a domestic policy angle, it still has to come to terms with this new reality.

- Defence spending as a share of GDP has increased significantly across the continent, and this is unlikely to fall anytime soon, thereby fuelling an economic sector that has been somewhat dormant.

- A new energy picture has markedly changed Europe’s industrial prospects, particularly in Germany and Italy. Storage levels are full, the mild winter has also lent a helping hand, and there is sufficient energy for the rest of 2023, but the question remains as to where new supplies for 2024 will be sourced.

- While the West has shown a strong commitment to sanctioning Russia at its own economic expense, it was surprised by the number of countries which refused to condemn Russia. The war has emboldened some countries to assert themselves on the international stage. India, for example, is benefitting from the US and EU’s efforts to distance themselves from China and feels no pressure to choose sides on the war.

- The war has put the importance of ‘nuclear’ (power and weapons) back on the agenda. From an energy perspective, domestic nuclear power has redeemed itself as an energy source that is somewhat more shielded from geopolitics than other sources. From a nuclear weapons perspective, the war has shown that nuclear powers have significantly more leverage. This will be the lesson learnt for many countries having witnessed Ukraine’s experience of giving up nuclear capabilities in exchange for failed security protection.

The war’s economic toll on Ukraine and the world

1| Beyond the terrible human cost, including a widespread exodus with over 5 million people displaced, Ukraine’s economy has been devastated by the conflict.

Over the year, GDP declined by over 30% and the damage done to its productive potential is, by most estimates, truly unprecedented. Three months ago, the estimated cost to reconstruct the war-torn nation ranged from $350 billion (World Bank) to $750 billion (Ukrainian government), but given the ongoing damage to critical infrastructure the final cost could exceed $1 trillion.

2| The short-term impact on Russia has been smaller than many economists anticipated a year ago.

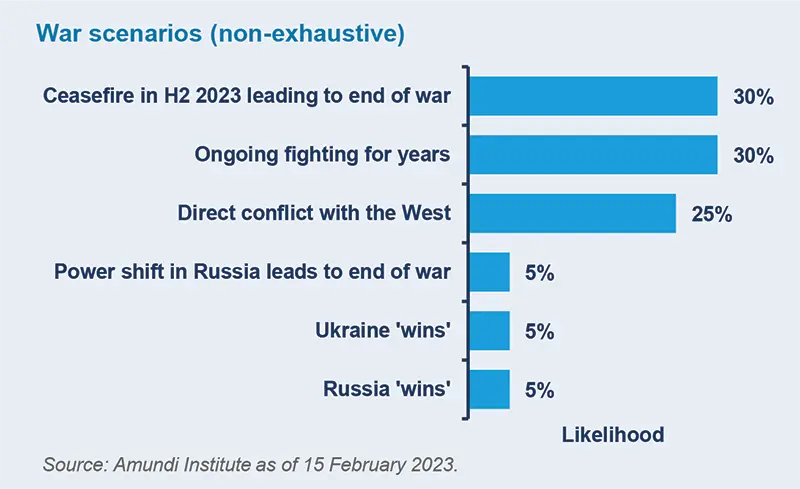

The Russian economy contracted by about 3%, whereas the consensus view expected a 10% decline. Western sanctions (until more recently) centred on Russia’s capital account, restricting Russia’s access to capital markets and freezing its sovereign assets held abroad, but left its main source of foreign income – energy exports – largely unscathed. Since Russia hasn’t needed foreign capital, the sanctions have not reduced Russia’s ability to finance its war effort.

But sanctions will have a more pronounced impact in the longer term. As the West, particularly Europe, reduces its dependence on Russian energy – as illustrated by the G7 price caps on Russian oil and embargoes on energy imports – Russia’s foreign income will drop substantially compared to last year’s windfall. Its current account surplus last month, for example, was already back to pre-war monthly levels. The war has increased Russia’s defence spending by 60%, but the sanctions and lower demand have reduced revenue from oil and gas exports by 40%. In the context of a weak domestic economy, the war effort is leading to a sharp deterioration of Russia’s public finances and unprecedented record fiscal deficits in recent months, limiting spending in other areas.

Sanctions on technology imports and a ‘brain drain’ of its human capital is a serious setback. Together with the fiscal drain from the war, this will severely dent the prospect of reviving already shrinking investments, as well as Russia’s long-held ambition of diversifying growth and reducing its dependence on energy exports.

3| The initial supply shock driven by a near-fivefold increase in gas prices and higher oil prices amounted to a 4% (terms of trade) hit to Europe’s GDP and contributed to the very sharp and sudden increase in inflation.

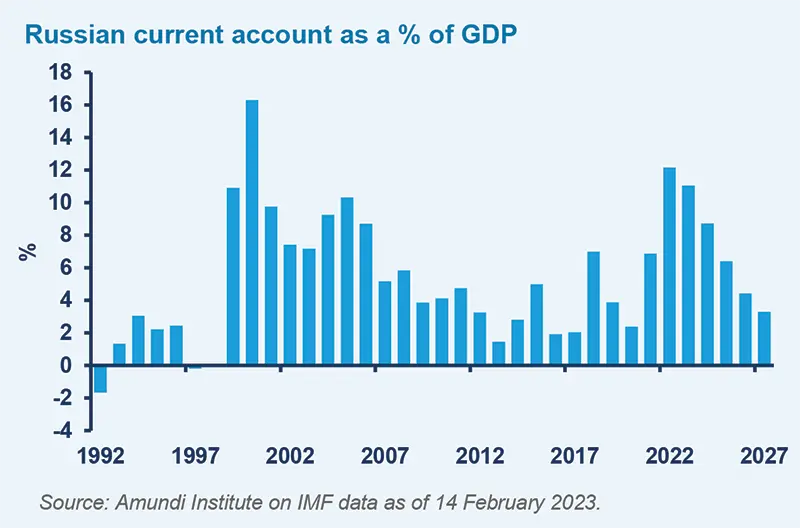

Europe has had to use much of its fiscal power to buffer the impact of rising energy bills and tighten monetary policy to ensure inflation expectations do not become entrenched at uncomfortably high levels. Finding alternative energy supplies, particularly natural gas, has been the bigger challenge. The mild winter, lower consumption, sourcing of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from other countries, and additional gas storage facilities have provided invaluable short-term support. The recent decline in wholesale gas prices has reduced the risk of a severe recession.

However, over the next 3-5 years, the global market for LNG will remain imbalanced, as demand from other regions (especially Asia) also rises. As production ramps up, the global supply of LNG should gradually increase, but prices will remain under pressure in the medium term and above the levels prevailing prior to the conflict: concerns about energy security will likely add a premium. Higher energy costs will reduce the international competitiveness of Europe’s more energy-intensive sectors, and affect the composition of growth in countries that are more dependent on industrial sectors, such as Germany and Italy. The 2011 nuclear power plant accident in Fukushima serves as a good example: Germany shut down its own nuclear plants, and its industry was suddenly faced with structurally higher energy costs, which was one of the reasons behind the shift of auto production to the US, Mexico and Eastern Europe.

Europe’s shift toward more renewable energy will undoubtedly help, but reducing its current dependence on fossil fuels is more of a 10-15 year prospect. The war has added a sense of urgency to the region’s climate agenda and its Net Zero objectives, and may reinforce policymakers’ resolve to speed up the transition.

4| Emerging markets (EM) and low-income countries (LICs) have suffered a much bigger economic shock.

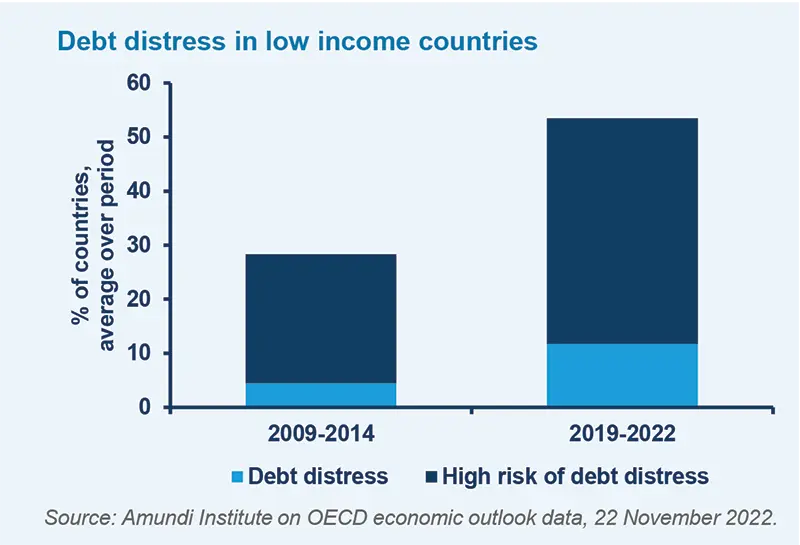

With higher weights of energy, commodity and food prices in their consumer price indices, inflation here has increased a lot more than in advanced economies. In most cases, governments lack the space for fiscal measures to cushion the impact of price shocks, and their constrained access to finances has rationed them out of energy markets, with many suffering power cuts and blackouts. With much lower access to foreign capital (capital flows to EM and LICs have halved since the pandemic), almost 60% of low-income countries (around 40 countries) are likely to be under severe debt distress, and many will be forced to restructure their public and private external debts.

While global economic integration – the cross-border flows of goods, capital, investment and ideas – effectively peaked a decade ago and has plateaued since, greater fragmentation stemming from the war has posed another setback to globalisation. Despite a recovery in the nominal value of global trade following the reopening after the pandemic lockdowns and supply chain disruptions, new trade restrictions have reduced countries’ openness to trade (aggregate global trade as a percentage of global GDP). The number of trade restrictions imposed around the world has grown from an average of 500 per year since the Great Financial Crisis to over 2,000 in the last two years. This increase in global fragmentation is a serious setback to the convergence of per capita incomes between countries that global economic integration has contributed to over the last three decades.

5| Central banks are already dealing with the consequences of the war, as well as the pandemic shock.

Monetary tightening in an environment of weak growth is challenging and requires a continuous assessment of the transitory factors (such as energy prices) behind the current bout of inflation. Policymakers have to balance the risk of overtightening against that of inflation expectations becoming unanchored from their targets. Fortunately, most market indicators of expected inflation suggest that monetary tightening has been sufficiently aggressive, with risks of adverse wage-price spirals still relatively low. In the longer term, however, commodity and energy prices may be volatile and subject to periodic bouts of volatility due to more uncertainty about energy supply and energy security. This will require a more proactive monetary policy compared to recent history, arguably driven more by data, and less by central bank forward guidance.

Implications for investors

Forcing the pace of fragmentation and the green transition.

The dynamics underlying a new geopolitical equilibrium are powerful. The Covid-pandemic and war in Ukraine have been important catalysts for a large-scale de-globalisation trend, characterised by shorter value chains, less intertwined economies, greater protectionism and higher inflation. Tangible shifts are taking place every day in corporate decisions, legislative acts and political statements. Additional issues, from human rights to pollution, have created additional barriers for financial markets to work in a truly integrated and global way. The most negative war scenario – that is, a direct military conflict between Russia and the West – would likely have extremely severe economic and financial repercussions. It would mean more upward pressure on production costs and inflation, making it harder for the ECB to employ a more accommodative monetary stance. Moving forward, we might expect to see military expenditures of around 2% of GDP, more government aid packages to households and enterprises, and a greater push towards the energy transition.

When it comes to energy, Europe has embarked on a long journey to reduce its dependence on Russia, sourcing new suppliers and increasing its use of renewables. This process will continue, regardless of a potential ceasefire or change in the Russian regime. The ECB may have to keep its balance sheet elevated to finance the Eurozone’s priorities, and there may be a bear steepening of yield curves.

A sudden end to the war would imply less of a bear steepening in bond markets and diminished inflationary pressures, paving the way for a less restrictive monetary stance. Nevertheless, corporate profitability will be affected by the energy transition, which relies on increased efforts on behalf of central banks, policymakers, and public and private support to finance the necessary capital expenditures. European corporates have a tall order to fill compared to some other international peers, given their still structural dependence on fossil fuels.

A nimble stock-picking approach is required in this environment.

Following a sparkling start to the year, European equities should gradually shed the ‘monetary illusion’ driven by inflated nominal revenues (as realised inflation is well above the percentage increase in wages), the depletion of accumulated savings, and the backlog of orders, which have supported consumption and employment beyond expectations. Moving forward, stocks could come under pressure from the slowly deteriorating environment, the compression of corporate margins, and the progressive increase in default rates. These developments may unfold much faster if the conflict in Ukraine escalates or drags on.

The case for greater financial fragmentation can also be seen in the race for semiconductors, artificial intelligence, electric vehicle components and biotechnologies for example. Global superpowers are competing to obtain leadership and independence in these sectors. Both Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping have made this clear in their political statements and stance. New legislation such as the CHIPS act in July 2022 – with a financing endowment of USD 280 billion – is aimed at reshoring and producing locally and shortening value chains.

Korea, Japan and the European Union have issued similar albeit smaller packages. While these trends are rooted in geopolitical issues, they also carry important opportunities for investors, due to the large and fundamental changes they embed.

In this deteriorating geopolitical landscape, commodities, and industrial metals and gold in particular, are appealing assets to hold, regardless of macroeconomic forecasts. Different war scenarios carry varying implications for soft commodities like cereals, which play an important role in inflation, particularly in emerging markets. A power shift in Russia or a Ukrainian victory would lead to a progressive normalisation in these products’ supply chains over the course of a few years.

Regarding foreign exchange, the war in Ukraine has imparted an important lesson: central banks will play a pivotal role, as illustrated by the freezing of Russian reserves, and will have to rethink their reserves allocations in light of the geopolitical balance that will prevail. While the war has had effects that, on the surface, appear transitory, it will also leave a deep footprint.

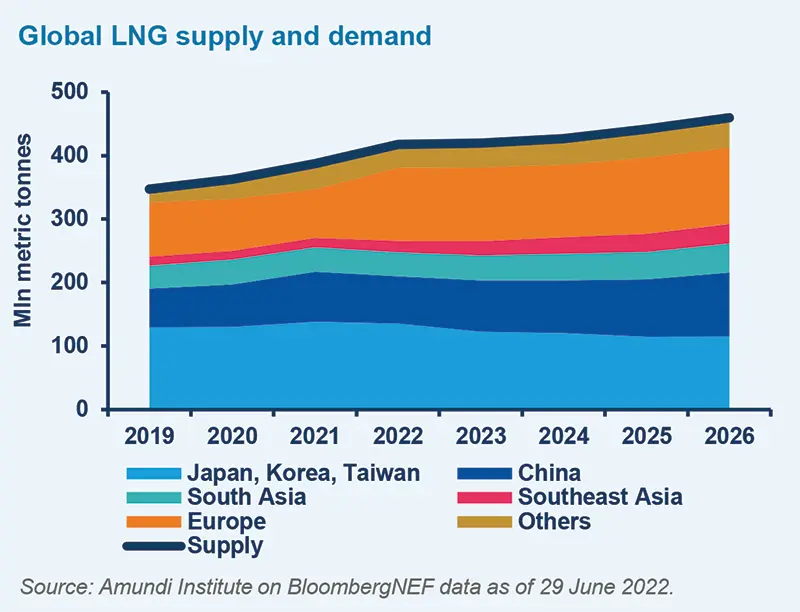

A bottom-up view of the impact on European equity

The war has defined winners and losers at the sector and company levels. The search for energy independence and the diversification of supply chains will remain key themes in the long term.