Summary

From sluggish to strong: Germany poised to support Europe’s growth

Key takeaways

Eurozone growth remains sluggish, but rising incomes, lower ECB rates, and strong household savings support a potential strengthening. US tariffs still pose a significant threat to key European industries like automotive manufacturing.

EU defence spending is increasing, but it still mainly benefits the US. Building a unified European military industry will take years even with broad political consensus. The European Defence Industrial Program (EDIP) aims to shift procurement within Europe to 50% by 2030, but challenges in financing and coordination make this a long-term objective rather than an immediate solution.

Germany’s new government plans to increase public investment through a €500 billion fund and loosen debt constraints on defence spending. This fiscal expansion could provide a fiscal stimulus of 1.5% to 2% of GDP annually from 2026, with potential spillover effects on other European economies.

Weak growth in the short term, but prospects remain favourable

Multiple surveys suggest that economic growth in the Eurozone remains sluggish at the start of the year, while labour market conditions have begun to weaken in several countries. Recent data also indicate a significant moderation in wages, with companies expecting an average increase of +3.3% over the next 12 months, compared with +4.5% at the same time last year. However, wages are still projected to rise faster than prices.

Despite these short-term challenges, the argument in favour of a recovery remains intact. Higher real incomes, lower ECB rates, and healthy household balance sheets are all factors supporting domestic demand. Notably, household savings have increased further over the past two years, with the average Eurozone savings rate up 1 percentage point since the end of 2021 (at 15.3%).

However, the trade tariffs announced by the US against Mexico and Canada reflect a looming threat that must be taken seriously. Increased tariffs would weigh heavily on European industry (particularly in Germany and Italy) and on the automotive sector, which would be among the most exposed. This creates significant uncertainty for European growth, as higher tariffs could severely impact key industries.

Monetary policy: the ECB will have to further ease monetary conditions

Although the debate is fixated on key interest rates, it is important to also monitor what is happening on the ECB’s balance sheet, which continues to shrink, down 25% from its peak in 2022. Since December 2024, the ECB has stopped reinvesting maturing PEPP bonds. In practice, this means ECB purchases will decline by nearly €500bn in 2025 compared to last year.

Rate cuts are exerting downward pressure, especially on the short end of the yield curve, while quantitative tightening (QT) is exerting upward pressure on long-term yields. The effectiveness of rate cuts on easing financial conditions is limited when the central bank’s balance sheet is contracting at the same time. Moreover, bank lending to the private sector is increasing rather slowly.

Loans to non-financial corporates grew by 2.0% year-on-year in January, significantly slower than their long-term average growth rate. The same trend is true for housing loans, which increased by just 1.2% year-on-year, compared with an average annual increase of 5.1%. Given this backdrop, the ECB is likely to maintain an accommodative stance to support economic growth.

Can defence spending in Europe and Germany change the situation?

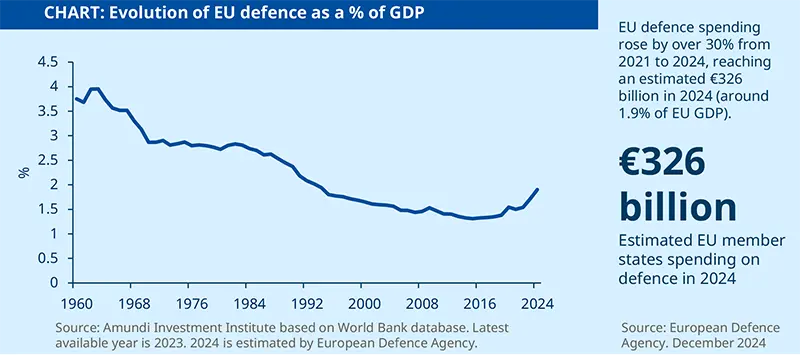

The EU spent 2% of its GDP on defence in 2024, compared to 3.4% in the US. Over the past decade, the EU's nominal defence spending has increased by more than 220%. This sharp increase reflects Europe’s strategic shift following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

The Munich Security Conference: a new era for Europe

The announced military disengagement of the US signals the beginning of a new era, where Europe must take responsibility for its own security, something it is not yet fully prepared to do. In 2024, Europe spent 2% of its GDP on defence but it must now rapidly strengthen its military capabilities. It is worth noting that in the 1960s, despite being protected by the US military umbrella, Europe spent between 3-4% of its GDP on defence.

The European Commission (EC), in line with most EU heads of state, has put forward several proposals to help Member States (MS) finance their increased defence commitments. On the one hand, the activation of the national escape clause within the Stability and Growth Pact will make it possible to finance defence spending at the national level. The measure should enable MS to allocate approximately €650 billion over four years to defence, bringing defence spending to 3.5% of GDP. There are also plans to set up a common mechanism of €150 billion structured in the form of loans to MS. In theory, these initiatives could mobilise €800 billion for European defence.

However, many countries with high debt levels, such as France, Italy, and Spain, will struggle to commit to such expenditure without either reducing other expenditures or increasing taxes. This could have significant consequences for economic growth and social stability.

Private financing remains a major challenge for the defence sector, particularly for SMEs and medium-sized companies, whose development is essential to the construction of a pan-European military ecosystem. However, it is too early to count on the mobilisation of significant amounts through this channel. Further details are likely to be provided in the White Paper on Defence, which will be released by the EC on 19 March.

As the US steps back, Europe faces the urgent task of strengthening its own defence, yet high debt levels and financing challenges could slow progress.

What will be the impact on GDP growth?

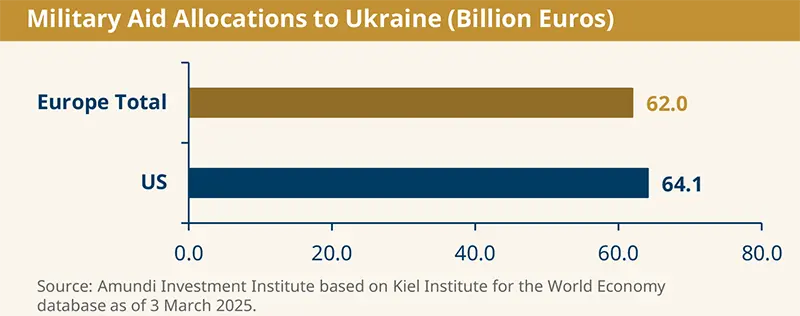

The economic impact of defence spending varies significantly depending on whether military equipment is produced locally. In the US, the multipliers are relatively high. In Europe, on the other hand, they are generally below 0.5, because a large part of the defence goods are imported (France seems to benefit from higher multipliers). In 2023, 70% of military purchases by EU Member States were made outside the EU, with the US accounting for over 60%. Moreover, less than 20% of EU defence investments were made jointly.

To address this issue, the European Defence Industrial Programme (EDIP), presented in March 2024, aims to develop and strengthen Europe’s military industry. The initiative encourages Member States (MS) to jointly procure defence equipment and to source 50% of it within Europe by 2030, increasing to 60% by 2035. The idea is to build pan-European supply chains, but there are many obstacles in practice.

Despite the political will, building a unified European defence industry will take many years. In the medium term, the good news is that this will enable Europe to boost its technological investments and its industrial base. But in the short term, in the absence of a single defence market, much of the EU's increased military spending will primarily benefit the US. This could help Europe avoid a full-scale trade war with the US, provided that Donald Trump refrains from taxing European exports in return.

Since much of European military spending still flows to the US, efforts to build a unified European defence industry will take years to materialise.

Germany: a special case

On 4 March, the CDU and the SPD (the two parties that will make up the next coalition government in Germany) agreed to have the outgoing chambers vote on two key measures:

A special fund (SF) with €500 billion (11.6% of 2024 GDP), enshrined in the constitution, for public investment in infrastructure over 10 years, of which 100 billion would be allocated to the states.

A reform of the debt brake rule for defence spending.

This marks a historic shift. Germany is one of the only EU countries capable of financing a major budgetary expansion through increased debt. In practice, these proposals mean that defence spending will no longer be constrained ex ante, allowing Germany to reach its target of 3% of GDP for defence spending as early as next year.

In addition to defence spending, public infrastructure investment would be set to increase by around 1% of GDP per year in the coming years. This would be enough to clear the investment backlog, which has accumulated to an estimated 15% of GDP, by 2035. Unlike defence spending multipliers, the fiscal multipliers for infrastructure investment are quite high (well above 1), meaning this spending will have a stronger impact on economic growth.

Ultimately, the proposals of the CDU and SPD should boost the German economy, but probably not before 2026, given the time required for implementation. However, the proposals have not yet been adopted: on 10 March, the Greens, whose votes are necessary to achieve a two-thirds majority in the Bundestag, opposed the reform of the debt brake, likely to secure concessions in other areas. The two-thirds majority in the Bundesrat will only be obtained with the support of certain ‘Free voters’. It is therefore premature to consider these proposals as a given.

Consequently, we our keeping our growth forecasts unchanged for Germany and, by extension, for the Eurozone this year. However, with a revival of infrastructure spending of 1% per year (50 billion), combined with an increase in defence spending from 1% to 1.5% (to reach a target of between 3% and 3.5% of GDP), we estimate that the annual fiscal stimulus for Germany could amount to 1.5% to 2% of GDP for several years, starting in 2026. The rebound in German growth will inevitably have a knock-on effect on its European trading partners, but this impact should remain modest, especially if other countries pursue fiscal consolidation at the same time.

Ukraine and Europe’s path ahead

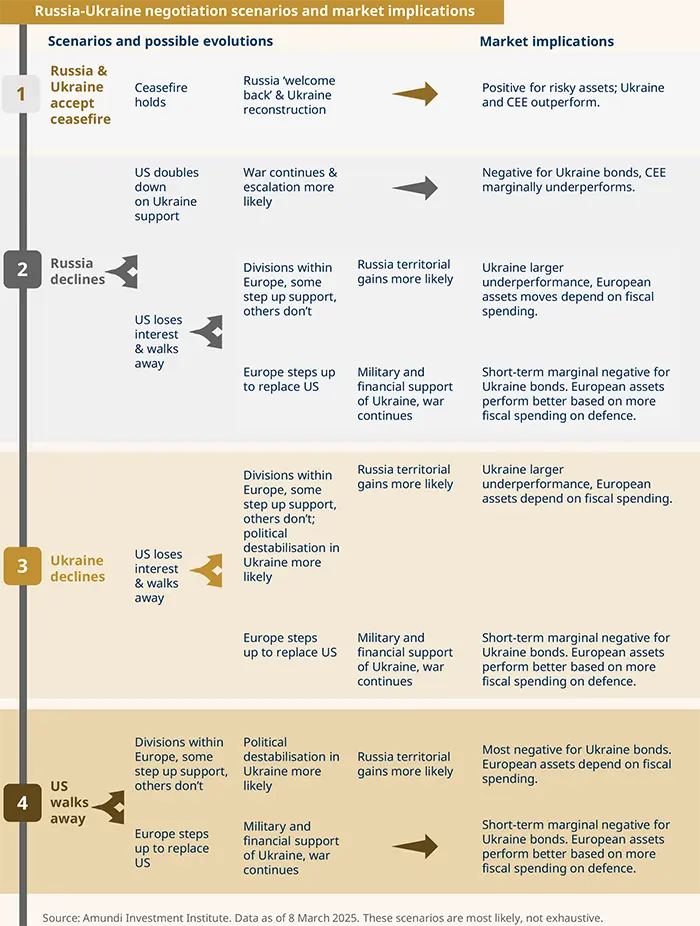

Foreign policy under the Trump administration has drastically shifted the dynamic between the US and its allies, ramped up pressure on Ukraine, and embraced Russia’s rhetoric on the war. In outlining the various scenarios for negotiations this year, we highlight what this means not only for the fate of Ukraine but also for Europe.

European leaders will likely follow one of these three paths in response to the US’s new stance: first, they may do ‘just enough’ and hope for the best; second, they may accept the weakening of Ukraine and the EU; or third, they may rise up to the challenge and reduce their security dependence on the US.

Path 1: Europe does ‘just enough’ and hopes for the best

The first path would see the EU and UK spending somewhat more on defence over time, while continuing to slowly improve the defence capabilities of the EU and individual countries. While Ukraine would receive more military support, European leaders would eventually accept that Ukraine would remain vulnerable to renewed Russian aggression. US protection, although wobbly, would still be regarded as the main pillar of European security.

Path 2: Accepting the weakening of the EU as a geopolitical player

The second path would see European leaders accepting that Ukraine’s future is in the hands of Russia (and a fickle US). Some countries would likely try to rekindle ties with Russia in the hope of reducing the military risk it poses. The EU would be significantly undermined as a geopolitical player, and fears would linger over Putin’s intentions beyond Ukraine.

Path 3: The EU and UK rise to the challenge, emerging as more powerful geopolitical players along the way

The third path would involve European leaders, or a strong-enough coalition of the willing with EU support, rising to the challenge. This would require making trade-offs, such as redirecting social expenditure towards defence spending, which would need to increase significantly to rival the US. Meanwhile, the integration of military capabilities and systems across Europe would need to accelerate at a rapid speed. Over time, the EU and the UK would emerge as a geopolitical power in their own right.

An alternative scenario would see the US reversing course and doubling down on its support for Ukraine, which would increase the odds of a direct war with Russia.

A step forward for Europe

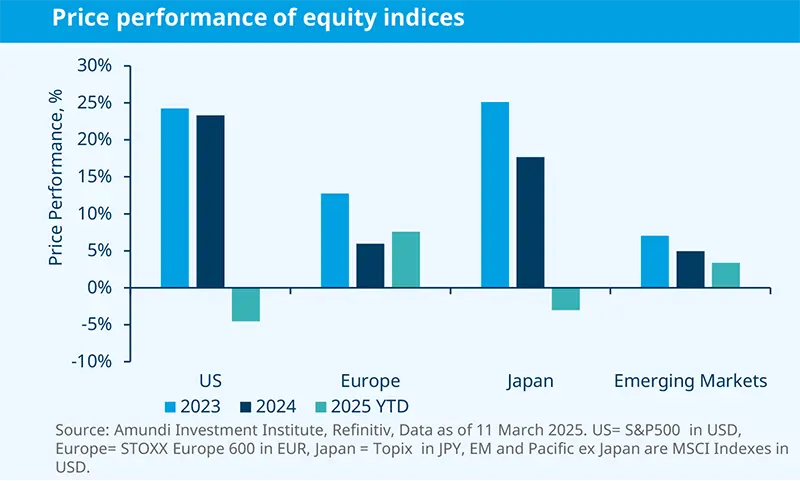

Over the past two years, the European equity markets (STOXX Europe 600) has underperformed the US and world indices (S&P 500 and the MSCI ACWI), largely due to the exceptionalism of the Magnificent 7. However, following this year’s DeepSeek shakeup, concerns have emerged regarding mega-cap valuations, creating opportunities for other stocks and regions to catch up. So far in 2025, Europe has outperformed both the US and other key regions, and there could be room for more growth.

European equities shine

Despite concerns over US tariffs, the Russian-Ukraine war, and an evolving European political scene, European equities are holding up well. Since President Trump’s inauguration, Europe has yet to be subjected to the widespread tariffs imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China, bringing relief to the Eurozone’s equity markets, as many analysts had feared the worst. And although Europe is not immune to US tariffs, we expect the tariff impact to be contained as only 6% of the sales of European-listed companies could potentially be affected if we exclude production carried out locally in the US and services.

As for the war in Ukraine, a ceasefire would have three implications: 1) a downward impact on energy prices, to which Europe is highly sensitive; 2) reconstruction in Ukraine, estimated at $524bn according to the World Bank, which should benefit companies in the region; 3) the need for structural decisions regarding defence independence. Lastly, the agreement between CDU/CSU and SPD (pending approval) for a major loosening of Germany’s fiscal situation will lead to significantly higher spending on defence and infrastructure and could prolong the rally.

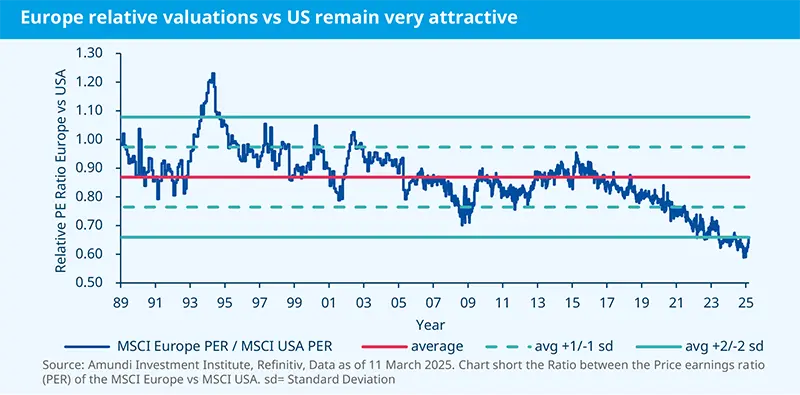

The case for a relative preference for Europe vs the US remains intact, as valuations are more appealing and the fiscal push could support earnings dynamics.

Scope for more

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, this type of relief rally in the European market relative to the US has occurred four times, lasting between four to twelve months and resulting in price outperformance of 9% to 22%.

The current rally in the STOXX Europe 600 has produced an outperformance of around +12% vs the S&P500 since the start of the year. Despite this strong rebound, Europe’s discount relative to the US has only returned to two standard deviations below the historical mean since 1988 (see chart above).

However, beyond a re-rating, transforming this rebound into a sustainable outperformance trend would require an improvement in earnings growth; currently, the consensus on Europe remains below other regions, such as the US, Japan, and EM.

Exposure to European markets makes sense and can be done with a pro-cyclical bias while still avoiding exposure to tariff hikes. In terms of style, mid-caps fulfill this approach with a number of other advantages, including lower valuations, stronger earnings growth than large caps, potential tax cuts in Germany, and benefits from Ukraine’s reconstruction. In terms of sectors, we favour Banks (due to yield curve steepening), Software (which is isolated from tariffs), and Aerospace & Defence (supported by structurally higher spending).

Opportunities in Europe beyond equities

European yields have risen, while US yields have fallen over the past month, driving the US-Germany 10Y spread to its the lowest level since July 2023. In the very short term, the move looks overdone; however, the fundamentals have changed. Risks to US growth have multiplied, while growth prospects – and expected issuance – have risen in Europe. Yet, European bonds can be supported by monetary policy. We expect the ECB to keep cutting interest rates, while we believe the Fed will not begin cutting until May. As a result, the spread in key rates could rise (albeit temporarily) to 225bp, pushing the 2Y spread between the US and Germany from the current 170bp to 180bp and the 10Y spread from 135bp at present to 160bp.

There may be even bigger opportunities in peripheral bond markets. The bold moves by the new German government on infrastructure and defence spending are likely to be echoed in other markets. Nonetheless, higher German spending – and strong growth in southern and Eastern Europe – still imply a continued tightening in Spanish, Italian, and other European spreads relative to Germany in the 5-10Y segment of the curve.