Summary

Road back to the benefits of international diversification

Over the past three years – well before the Covid-19 crisis – we have been arguing for a macro-financial regime shift, initially driven by the retreat of global trade as the main driver of global growth. The Covid-19 crisis has acted as a trend accelerator due to its de-globalisation footprint and implied supply-chain bottlenecks. Many growth engines have been re-shored, while the unified central bank model has ended.

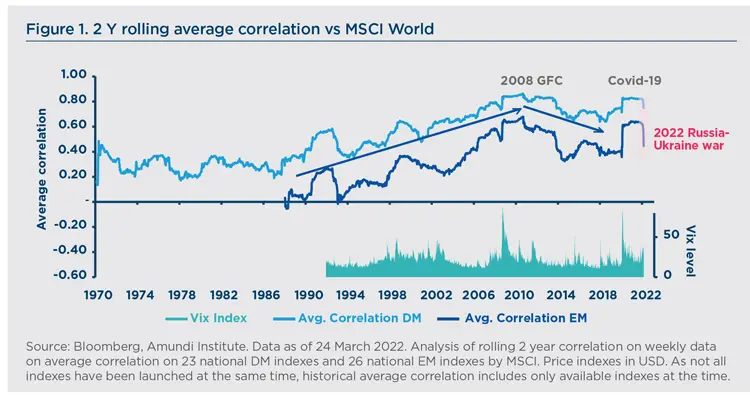

We no longer envisage a synchronous global economic cycle. Rather, we may observe regional cycles and increasing fragmentation at a country level, suggesting country risk is back with a vengeance. More recently, the Russia-Ukraine war has reinforced the case for country divergences by adding geopolitical risk to the mix, and pushing inflation unevenly higher due to different impacts stemming from higher commodity prices and supply - demand mismatches. Different country exposures to inflation and, consequently, different room for action from central banks add to a fragmented puzzle.

Amid these exceptional transformations we believe now is a good time to look into long-term trends and lessons from the past in relation to absolute and relative returns – for both safe and risky assets – and regarding diversification benefits and traps. Our aim is to assess whether these trends may be confirmed or be challenged by the ongoing regime shift.

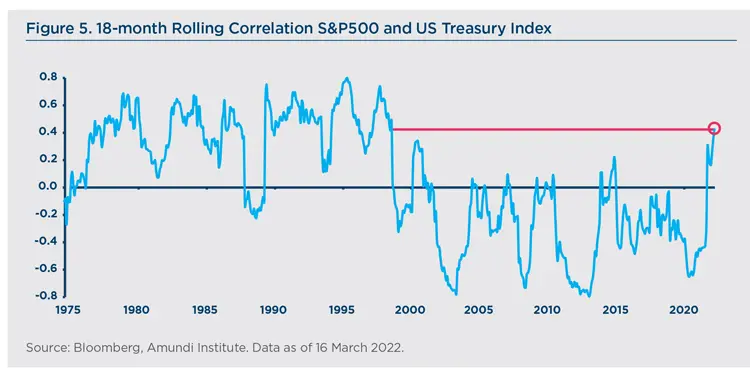

Looking at the past, we have already seen unexpected changes to well established correlation or return dynamics that have prompted investors to rethink their asset allocation approach. In 2008, during the Great Financial Crisis, investors thought they were diversified across asset classes but they were not as the majority of asset classes proved to be correlated during the turmoil. Hence asset class diversification brought little benefit during the worse of the crisis, when the only real diversifiers were safe-haven assets such as Treasuries and gold. Investors’ initial enthusiasm for factor-based allocation has resulted in some disappointment as unorthodox monetary policies have possibly weakened, at least temporarily, the power of factor diversification. More recently, traditional correlation metrics have started to break up in the face of inflation (e.g., equity/government bonds correlation turned positive) further questioning the traditional diversification framework.

The ongoing regime shift of high inflation will bring key implications for investors. With rising fragmentation and lower cross-country correlation, the benefits of global diversification is coming back in focus having been severely weakened by the effective correlation of global portfolios to the single factor of global trade.

Under such a fragmented scenario – featured by high and rising inflation – real returns will take centre stage, as investors look for sources of positive real returns and for exposure to assets that are correlated positively to inflation. Against such backdrop, we believe investors should revisit their strategic asset allocation framework and focus on three principles:

- Safe assets will prove less safe than was believed and will require investors to broaden their investment universe in the search for inflation protection. It’s time to reconsider the role of government bonds in asset allocation, as they will likely disappoint investors in the new regime and look for additional sources of real positive returns. Core allocations to government bonds should be reduced, investors should look for regional assets with the potential to deliver positive real returns as well as inflation linked securities.

- Global equities and real estate deserve a higher allocation and should see greater benefits from international diversification. Higher fragmentation of the economic cycle and the geopolitical reordering will drive up cross-country return dispersion after several decades of ‘sleeping integration’ driven by the high co-movement of global risk. Hence, in a world of low real returns for safe assets, investors should increase their allocation to risky assets, provided they enlarge their global perspective (including EM) and real assets.

- The correlation of safe assets versus risk assets is turning positive, as the inflation factor drives both asset classes. Hence, investors should consider structurally seeking to increase diversification by looking at real assets, gold, currencies and investment strategies that exhibit low correlation with equities and bonds.

The starting point for detecting what can be maintained from the past and what will likely change is an assessment of established long-term dynamics in terms of real returns and correlations. Building and developing on some assumptions from the work of Oscar Jordà et al. (who have estimated the real rate of return for everything from 1870-2015, with a focus on developed markets) we discuss the possible trends that should be maintained and sustained, as well as the aspects that should be revised as we should expect major looming changes.

Safe assets are not so safe, especially in higher inflationary regimes

In a regime characterised by high and rising inflation, real returns will take centre stage, as investors look for sources of positive real returns and for exposure to assets that are positively correlated to inflation. In this respect the first assessment regards real safe asset returns – including bonds and bills.

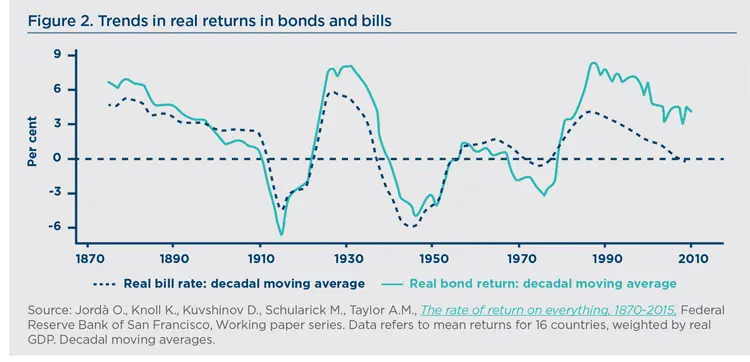

These have been very volatile over the long run. Real safe rates proved to be very low (even in negative territory) during world wars (WW) and during the 1970s’ stagflation episode, generally weighed down by inflation and the flight to safety (see Figure 2). They peaked between the two world and in the mid-1980s. At peacetime periods, safe real returns have been in the 1-3% range for most countries.

In addition, real safe returns have generally proved to be lower than real GDP growth, entailing low financing costs for governments especially after the world wars when low costs helped to repay the debt legacy from the war during an environment of financial repression. This proves critical today, as negative real returns in government bonds may help ease pressure on government finances, allowing for a rapid reduction of the debt accumulated to fight the economic damage from the Covid-19 crisis. This will be highly relevant in Europe, where the debt burden could be further exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, as the area faces the challenges of increasing energy independence and building a common defence proposition.

The long-term picture, as said, has proved to be one of low real rates, but it is also important to look at real safe returns with regards to inflation and in terms of regional diversification.

The positive correlation of real safe returns with inflation has been observed in the past and has not fully compensated investors. This is an important message for investors moving into the new regime. A positive co-movement of cross-country real safe returns was also evident. This aspect of globalisation, reinforced by the adoption of a homogeneous central bank model based on independence and on the same reaction function, is unlikely to be sustained in the current shift, as we enter into a fragmented puzzle of reactions, challenging the central bank reference model.

Overall, we believe that the regime shift will imply low/negative real returns in safe assets with potentially higher volatility, but also greater diversification among real returns in government bonds across regions where economic cycles and geopolitical risks differ. This calls for revisiting the core bond allocation with the addition of selective EM bonds that can provide positive real rates and also into inflation linked bonds, to seek inflation protection.

Equity and real estate: rising diversification benefits means risky allocations can be increased as overall risk should be lower

Before WWII global equity and global real estate returns were correlated, while after WWII they became uncorrelated. At the same time, equity markets were increasingly correlated across countries (see Figure 3, left chart), particularly after the ‘80s amid rising globalisation in financial markets (global electronic trading facilities), while cross-country housing returns remained uncorrelated likely reflecting a more fragmented investment backdrop and we believe they will continue to do so.

Consequently, country diversification in global equities has not been highly beneficial, but this is likely to be challenged under the current regime shift, as the emergence of more regionally de-synchronised market cycles and regional geopolitical risk factors will drive market movement in different directions.

In terms of real risk-adjusted returns, housing has shown a better risk-return profile due to its lower volatility (see Figure 3, right chart), while the total returns of equity and housing have been comparable. However, investors should also keep in mind that the liquidity profile of housing and equity are very different, with the first showing lower volatility but also lower liquidity and the latter being more volatile due to its high liquidity (it is often the first risk asset to be sold during a risk-off movement as it offers high intraday market liquidity).

For investors, international diversification will be back in the equity space. This supports the case for an internationally diversified portfolio of real estate and equities as a relevant core component of the overall asset allocation. This is also crucial for targeting positive real returns given that the safe assets engine is likely to be under pressure. In fact, a global mix of equity and housing in risk asset allocation should not only benefit from the low correlation among and within the two asset classes, but could also help to build a more balanced liquidity/volatility profile.

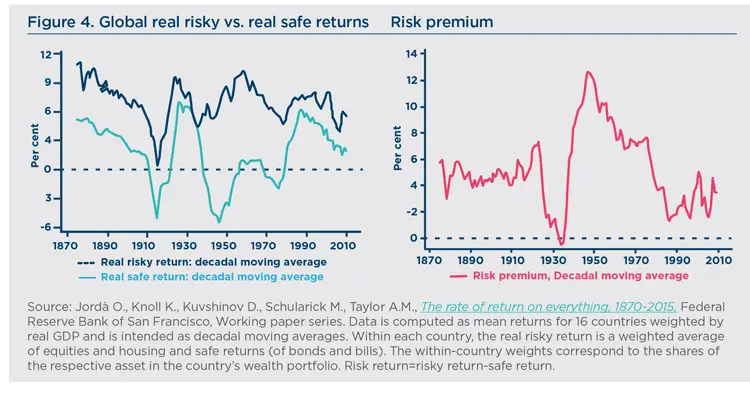

The risk premium and risky versus safe allocations: expect the risk premium to be volatile amid higher volatility in safe real returns and a breakup of traditional correlation dynamics

Over the long run, the risk premium (risky return – safe return) has proved volatile – more volatile than business-cycle swings – mostly due to changes in safe real rates, which have been very volatile and have even fallen into negative territory (see Figure 4, left chart). On the other hand, risky rates have been high and stable. This evidence does not fit with the narrative of secular stagnation, though the shortage of safe assets may have played a role on the safe asset component, just like the positive discount rate effect on risky assets.

The risk premium has fluctuated overtime. Before WWI, it was low and stable in the 3%- 5% range (see Figure 4, right chart). It rose somewhat following the war and fell to an all-time low around 0% in the 1930s. After WWII, the risk premium widened dramatically reaching its peak in the 1950s, before moving back to its long-term average.

The widening of risk premiums during wartime and in the interwar years was mostly a phenomenon of collapsing safe returns rather than dramatic spikes in risky returns. Risky returns have often been smoother and more stable than safe returns (see Figure 5, left chart), as the latter seems to absorb almost all adjustments. This is a puzzle in need of further exploration.

Risky and safe returns have been correlated on average historically and this is also the reason why investors have traditionally built their strategic asset allocation around a mix of equities and Treasuries.

Such correlation weakened during the previous regime initiated by the arrival of Paul Volcker at the Fed in 1979 before turning negative from the late 1990s onwards (see Figure 5). Recently this trend has reverted with correlations becoming positive again and reaching levels not seen since 1998.

In our view, the return of inflation points to the positive correlation between safe and risky assets, as both the efficient frontier and the utility function of bonds could change, no longer being the dominant diversifier. As the common driver of this correlation dynamic is inflation, investors should seek to increase diversification by looking to add real assets, gold, currencies and investment strategies that exhibit low correlation with equities and bonds.

Bibliography

- Blanqué, P. (2014, 2019 3rd ed.), Essays in Positive Investment Management, Economica, Paris.

- Blanqué, P. (March 2021), Shifts & Narratives #14 - Russia conflict marks a further step in the road back to the ‘70s, Amundi publications.

- Blanqué, P. (October 2021), Shifts & Narratives #10 - China is finally emerging from the US’s shadow, Amundi publications.

- Blanqué, P. (May 2020), The Day after #1 - Covid-19: the invisible hand pointing investors down the road to the ‘70s, Amundi publications.

- Blanqué, P. (June 2019), The road back to the ‘70s, implications for Investors, Amundi publications.

- Jordà O., Knoll K., Kuvshinov D., Schularick M., Taylor A.M., The rate of return on everything, 1870-2015, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working paper series.