Summary

- Post-war pension systems in the Eurozone were developed on the basis of two distinct logics: contributions and defined benefits. Today, all systems have become hybrid.

- Faced with the demographic challenge, all Eurozone countries have undertaken various reforms of their pension system.

- Northern countries are now doing better on financial sustainability than southern European countries because of reforms.

- In all countries, a core reform has effectively raised the retirement age or increased the contribution period. The sustainability of these systems remains to be monitored over the next 20 years.

- Tightening budget constraints in countries with high debt levels and ageing populations are exacerbating the need for savers to build supplementary and funded pension plans.

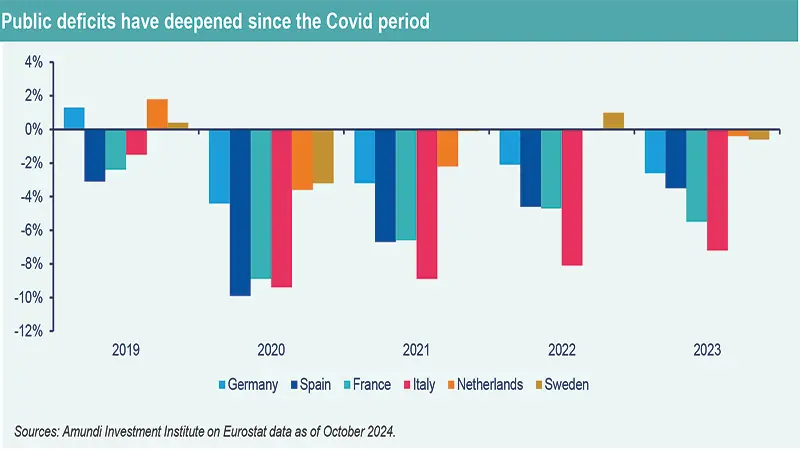

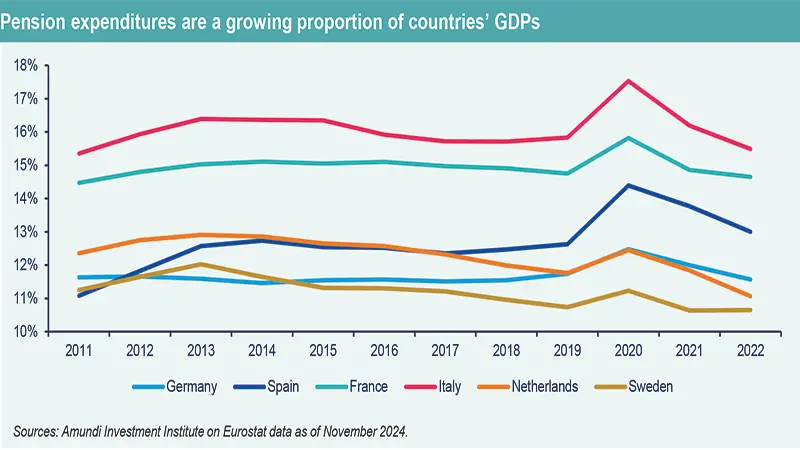

The issue of pension systems in Eurozone countries is significant because pension outlays represent a substantial portion of GDP. And an ageing population increases financing needs. At the same time, country deficits – and consequently debt – have deepened during the Covid period, including through higher interest rates1.

Over time, pension expenditure contributes to the rise of public debt, in particular in countries where pay-as-you-go schemes predominate. Households will have to save more for their retirement, especially in countries that need to consolidate their public finances. That said, all pension schemes may find it difficult to generate sufficient returns, especially if economic growth is too weak.

The variety of pension systems in the Eurozone are the result of the history, culture, and economic situation of each country. What are their commonalities or differences? What reforms have been undertaken to maintain the sustainability of their pension systems?

Six countries are studied in this context: Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and Sweden2 . The first 5 countries – the major historical countries of Europe – have long been facing the challenges of an ageing population. This is a lesser concern for other countries that joined the EU recently (Poland, Slovakia, Cyprus, etc.).

What are the major historical pensions systems? What remains of them today?

Historically, there are two types of pension systems in Europe that emerged after World War II: the 'Bismarckian' system and the 'Beveridgean' system. The former, that originated in Germany is based on defined contributions: each worker receives a pension based on their contributions to the system during their working period. This system is generally managed by social partners. The latter was developed in England based on a redistributive principle: universal coverage funded by taxes and organised by the state – broadly called the defined benefit system.

Today, there are hybrids of these systems in all countries, but all have established minimum pension levels, or social minimums3.

Importantly however, reforms have led to the development of funded pension systems alongside the pay-as-you-go system, in which active workers’ contributions pay for pensions of the retired. In funded systems, contributions are accumulated in pension funds, entitling contributors to receive benefits upon retirement.

Therefore, there is no longer a typical pension system – each country has its own specific features and various degrees of complexity. The simplest is the Netherlands, with a uniform basic pay-as-you-go pension for everyone, supplemented by a funded pension contracted by the employer.

There is no longer a typical pension system – each country has its own specific features and various degrees of complexity.

What reforms have been undertaken?

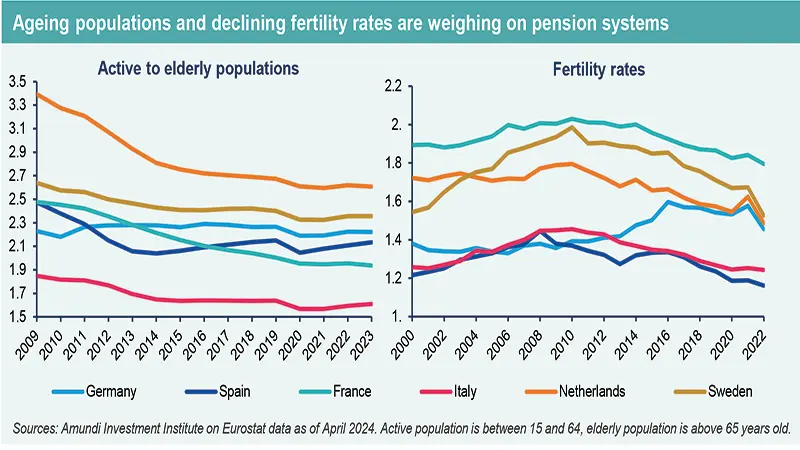

Since the 1980s, the pension systems in these countries have been facing the demographic challenge of an increasing proportion of elderly people in the population relative to the number of working individuals capable of financing pensions. This trend is linked to declining birth rates combined with rising life expectancy4.

As a result, these countries have undertaken reforms aimed at balancing their pension systems, some long ago like Sweden, others much more recently like Spain.

The various reforms undertaken in recent years have focused on different factors:

- Increasing the retirement age;

Lengthening the contribution period.

At least one of these two criteria has been tightened for the six countries studied5 :

- Reduction in pensions: by incorporating demographic factors into the pension calculation, as in Sweden, Germany, or the Netherlands, or through increased taxation or effectively reducing the real value of pension by not indexing payment to inflation, such as in France;

- Increasing contributions, as in Spain.

Pensions: a significant proportion of public spending

Pensions account for a significant proportion of public spending, but this varies greatly from country to country. In France, the financing of pensions represents a significant proportion of the State budget.

Although France does not have the highest proportion of pensioners in Europe, it does have a high level of pension spending (14.7% of GDP), which is around 2.5 percentage points higher than the European average (12%). In Europe, only Italy (with 15.5% of GDP) has higher spending than France. On the other hand, pension spending is lower in the Netherlands (10.7% of GDP).

All in all, the share of pensions in public spending is lower in France (24.7%) than in Italy (28.8%), but both countries are above the European average (23.9%). Conversely, this share is particularly low in the Netherlands (14%).

What is the sustainability of these pension systems?

European economies have long been faced with the question of whether their unfunded/underfunded public pension systems are sustainable. The pay as you go system is based on intergenerational solidarity, and therefore assumes that a sufficient number of workers contribute (with real wages rising in line with their productivity gains). A fall in the working population or in real wages will affect the equilibrium of pay-as-you-go systems. And this problem is all the more important given that pensions represent a significant proportion of the economy (% of GDP), and that the level of debt is high6.

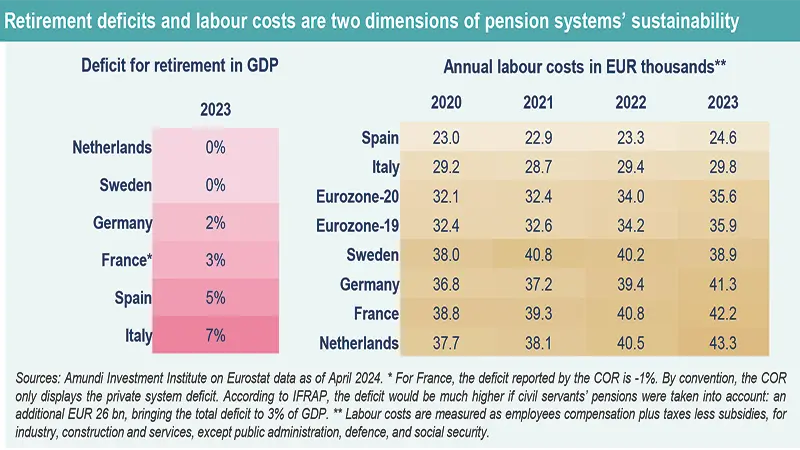

Sustainability has several dimensions: deficits of the state and of the pension system, tax pressure on labour income,living standards of retired households, and the intergenerational and gender equities of the systems.

In ‘pay-as-you-go’ schemes such as France's, the pensions paid are, in principle, funded by contributions deducted from the working population. In a ‘funded’ scheme, however, working people contribute to pension funds that acquire financial securities on their behalf, the proceeds of which are then used to pay their pensions. Naturally, this changes the stakes for public finances..

In principle, in a pay-as-you-go scheme, pensions are funded by contributions each year (or over a cycle). The contribution rate is set by the government. The scheme remains balanced if the rise in the dependency ratio is offset by the fall in the average replacement rate or by a rise in the contribution rate.

In practice, however, pay-as-you-go schemes are rarely ‘pure’ and contributions and benefits do not necessarily balance out. Pensions can be revalued (for social or equity reasons, for example) and the resources of these schemes include a large proportion of taxes and subsidies. Put another way, an increase in the dependency ratio can lead to a deterioration in the financial sustainability of pay-as-you-go pension schemes, and therefore to a fall in the replacement rate and/or an increase in the contribution rate.

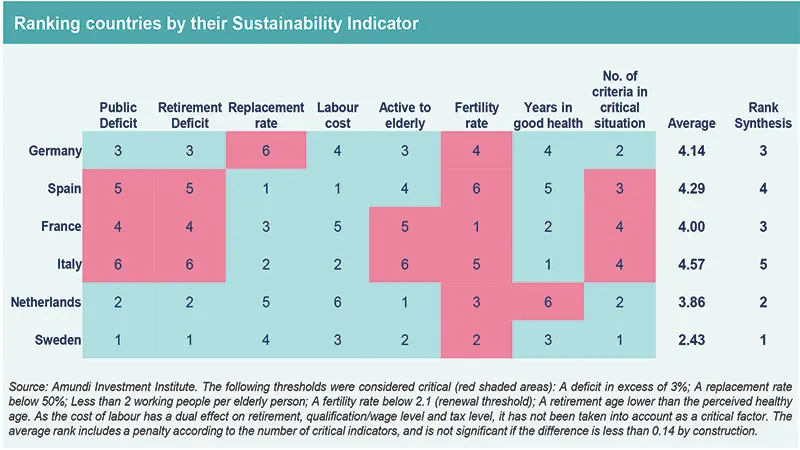

From the perspective of deficits, the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden are the most virtuous. Furthermore, controlling the taxation of labour is key to maintaining the country's international competitiveness. Labour costs are thus highest in the Netherlands, Germany, and France. However, these are also the countries with the most skilled workforce and higher productivity.

A 2023 CEPR study7 on the fiscal capacity of governments to finance pensions, based on the Laffer hypothesis (too much taxation kills taxation), compares the position of different countries. France and Italy emerge as the countries with the least fiscal leeway on wages to counter a rapid decline in pension levels. The Netherlands, Germany, and Spain are in a slightly less critical situation.

It also shows that consumption taxation as a means of financing pensions is a fiscal alternative that results in better per capita welfare than increasing the retirement age (or contribution period), with an equivalent outcome on the pension system's balance

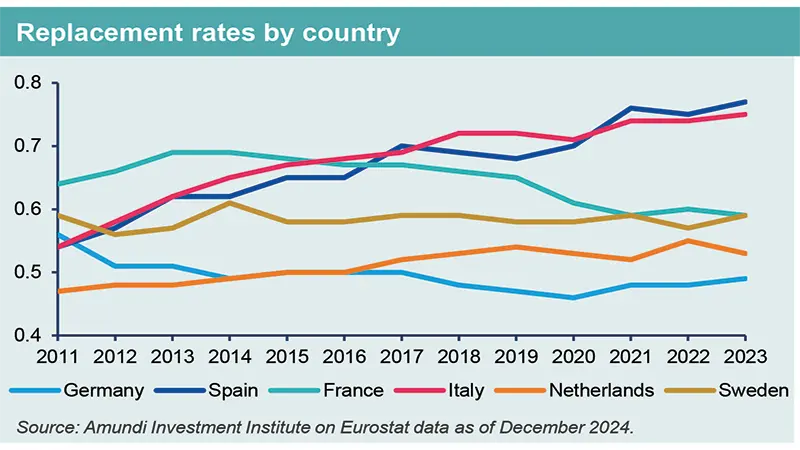

In terms of pensioners' living standards, pensions represent between 48 and 75% of final income for the countries studied. At the top of the scale are Spain, Italy and France, the countries with the highest pension deficits. Sweden and the Netherlands follow. Germany is at the bottom of the scale.

To alleviate the cost of financing first pillar pensions, the German government has proposed a bill: they plan on launching a state-funded pension fund invested in capital markets, which is expected to reach EUR 200bn by 2036. The fund will be financed with approximately EUR 12bn a year in the form of government loans. Additionally, EUR 15bn in federal government assets and liquidity will be used to finance the fund by 2028. The current pension replacement rate of 48.2% is guaranteed until 2025. But without a change in the law, the current employee contribution rate of 18.7% is set to rise to 21.1% by 2037, and the replacement rate to fall to 45%. With this fund, the government aims to guarantee current pension levels until 2039, by limiting the increase in contributions.

In Sweden, a country with a balanced pension system, some retirees face poverty issues. These are mainly women, as women's pensions are on average 30% lower than men's, or men forced to retire early. Indeed, the inequality in replacement rates compounds with income inequality.

The average replacement rate decreases in France as the required contribution period increases, which is something to monitor.

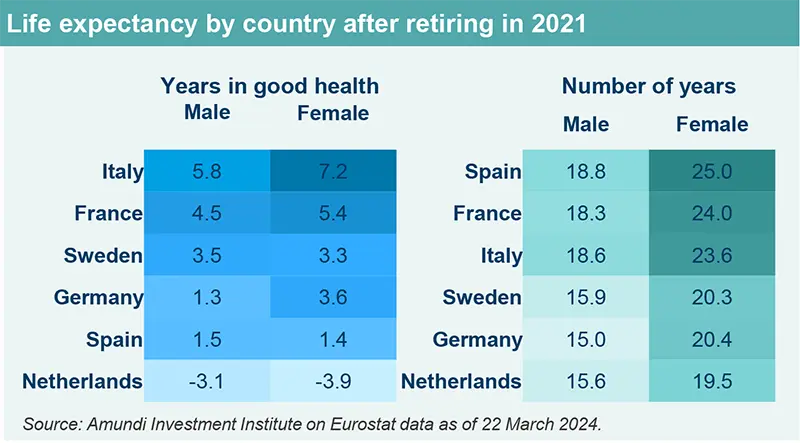

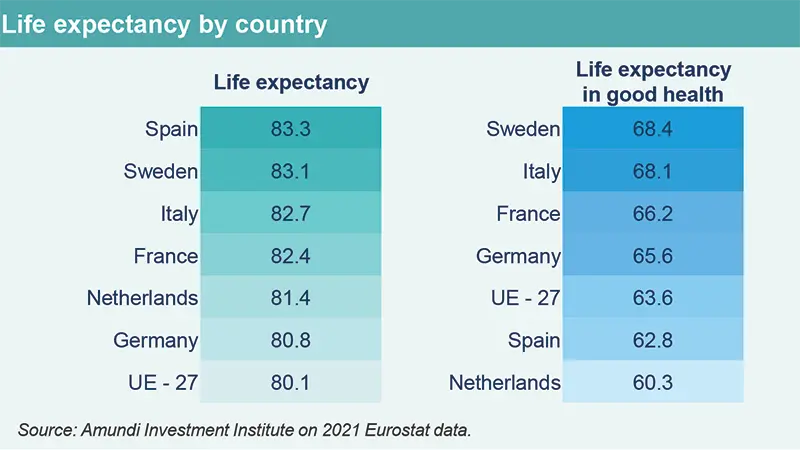

Regarding intergenerational equity, greater variability in replacement rates can pose problems. Similarly, life expectancy and remaining in good health after retirement is a factor for intergenerational equity. This is negative in the Netherlands.

The ranking of the 6 countries relative to each other regarding the aforementioned indicators, with a focus on indicators reaching a critical stage, shows that the 3 countries in the most critical situations are Italy, Spain, and France. In contrast, Sweden and the Netherlands demonstrate a more sustainable system.

The question is whether economies in critical fiscal situations have sufficient room for manoeuvre to maintain their underfunded public pension systems.

Even if the reforms undertaken are heading in the right direction, there is no guarantee that they will ensure the sustainability of pension schemes. Indeed, an ageing population coupled with low productivity at constant employment, will exacerbate the threat to pension systems in the medium term. This is because weak potential growth in an environment of higher interest rates and elevated debts would inevitably tighten the budget constraint, which could ultimately result in a further fall in replacement rates and an increase in contribution rates.

Despite significant differences, the room for manoeuvre (called ‘pension space’) to finance public pensions through additional taxation of earned income over the next 30 years already appears limited in many countries. The CEPR study cited above finds that in 5 countries (Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain), pension space is between 10 and 25% (i.e. expenditure on public pensions is at least 25% less than the maximum revenue that can be generated by labour taxation). For 4 countries (Belgium, Austria, France and Italy), the ‘pension space’ is already less than 10%. And for France and Italy, there will be no pension space by 2030.

With another methodology, the Mercer CFA Global Retirement Report finds similar conclusions. Considering 50 indicators including retirement benefit levels, system sustainability, and governance quality, it highlights the Netherlands as the top-ranking country8 . France, Spain, and Italy are identified as presenting significant risks or problems. The report suggests developing a funded pension system.

To face this retirement challenge (and even more so in countries where the Sustainability Indicator is critical), it seems important for individuals to supplement their government funded pensions with savings set aside though out their life.

The multiplicity of evolving regulations between countries, and the diversity of personal situations and retirement goals, underline the need to develop individual and customizable solutions. These solutions should not be designed in isolation: they should be engineered with the understanding of all the sources of pensions an individual can get, be them from the first,

second or third pillars.

Conclusions

All pension systems in the Eurozone, regardless of their specifics, are currently facing the demographic challenge of the 'grandpa boomer' phenomenon and will continue to do so for the next 20 to 25 years. They have all undertaken reforms, whether related to retirement age, contribution duration, pension levels, or contributions, the effects of which are still to come for many of them.

The most resilient, balanced, or even surplus-generating pension systems are those of the Netherlands and Sweden. Sweden, for instance, faces issues of poverty mainly among retired women, and the Netherlands has already surpassed the perceived healthy retirement age as the age of departure from the labour market.

However, the countries currently in the most critical situations are Italy, France, and Spain.

France and Spain have implemented new measures in 2023, and the ambitious early retirement measures implemented by Italian governments appear to have ended. Whether these measures, along with those implemented by Germany, will be enough to durably balance the pension systems of these four countries remains to be seen.

The increase in public debt and the budgetary constraints imposed by the Stability and Growth Pact will force countries in a critical situation to implement fiscal consolidation measures in the coming years. With replacement rates falling, and a possible increase in taxation looming, it is more important than ever for savers to develop a supplementary pension scheme.

Appendix

Pension system deficits

There is no official, unified database in the Eurozone on government expenditures to cover pension system deficits. There are certainly several reasons for this, including the fact that taxation in the eurozone countries remains the sovereign domain of each country, and the highly political nature of the subject. The figures in Table 1 (deficits for retirement) have been taken from a variety of sources (economic newspapers, forecasting organisations) and are provided for indicative purposes only.

Demographic factors

The number of working people per person aged 65 and over, observed and projected for 6 countries, is declining significantly, a trend anticipated until 2050/20609 . The decrease in the number of active workers per elderly person is due to declining birth rates and increased life expectancy. The birth rate is falling steadily, well below the replacement threshold of 2.1 children per woman. In 2021 in the European Union, the average life expectancy at birth was 80.1 years, and the average life expectancy in good health was 63.6 years10. Life expectancy tends to be higher in Western Europe than in Eastern Europe. The post-war birth boom of 1946 to 1974, the so-called “Thirty Glorious Years” of rising living standards and mass consumption, is creating a ‘grandpa-boom’ today.

Retirement ages

Statutory retirement ages are gradually being raised, reaching or exceeding healthy life expectancy in some countries.

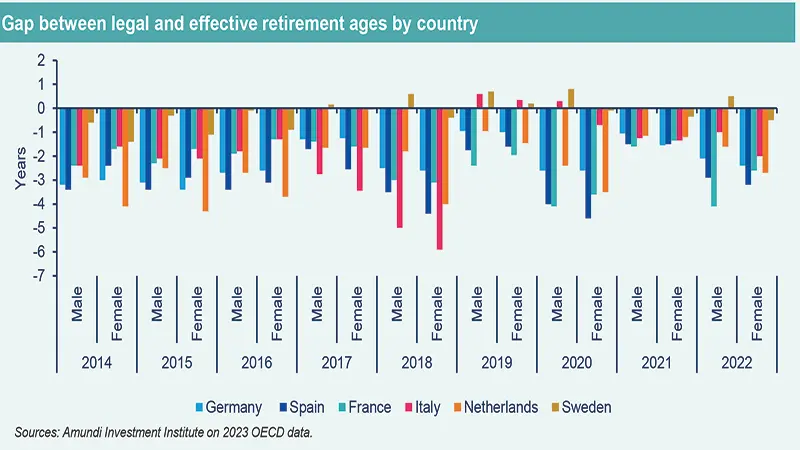

Labour market retirement ages are in practice different from legal retirement ages, as shown in the chart overleaf.

What are the factual reasons for these differences?

Apart from the legal derogations on retirement ages listed below by country, it is a fact that older people can also find themselves prematurely outside the labor market (disability, unemployment halo, etc.).

In Germany, it is possible to retire 2 years before the legal retirement age, without a discount for those who have worked 45 years (a period made possible by the practice of apprenticeship), or with a discount if the length of employment exceeds 35 years. Many workers opt for early retirement.

In Spain, it is possible to retire early at 65 if you have paid contributions for a certain length of time (36 years and 6 months in 2018, and an additional 3 months per year thereafter), or at 60 with the mutualist condition. There are also other possibilities for early retirement, such as partial or flexible retirement, or for jobs considered dangerous. The minimum contribution period is 15 years.

In France, early retirement is possible in certain cases (long careers, special schemes, arduous working conditions, etc.), but a minimum contribution period is required to qualify, otherwise the pension will be reduced. In the general scheme, the contribution period is gradually being extended from 42 to 43 years.

Italy abruptly raised the retirement age from 64 to 67 in 2012 (66 years and 7 months for women). However, two transitional reversals have been made: one with the 5 Star Movement and the other with the current government, making retirement possible from the age of 62 with contribution conditions of 41.10 months for women and 42.10 months for men. The minimum contribution period is 20 years.

In Sweden, the statutory age applies to the general pension, but most professional agreements stipulate a minimum age of 65 for receiving an occupational pension (90% of employees have one). Age 65 is also the minimum age for state-funded guaranteed pensions for low-income earners. The notion of length of contribution is not taken into account; what determines the retirement age is much more the level of pensions, which are subject to a conversion criterion based on life expectancy. However, 40 years is the length of time required in the country from age 16 to 64 to receive the full guaranteed state pension for low-income earners.

The variability of required contribution periods is largely a function of each country's labor market.

1.See the insert on pension system deficits on page 7.

2.Sweden is not a member of the Eurozone and the Swedish Krone is not yet within the exchange rate mechanism (ERMII).

3.OECD Pensions Outlook 2022.

4.See the insert on demographic factors on page 7.

5.See the insert on retirement ages on page 7.

6.Countries without pay-as-you-go pension systems can also experience high levels of debt. The real challenge for all economies is to increase. productivity and maintain growth despite an ageing population and the risks associated with climate change. And for individual savers, to be able to diversify their resources when they reach retirement age.

7.Heer, B. et. al., (2023), ‘Pension system (un)sustainability and fiscal constraints: A comparative analysis’, CEPR Discussion Paper, DP18181.

8.Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index 2023.

9.Eurostat data base, induced active population with a constant activity rate averaged over 9 years, April 2024.

10.Eurostat data base, life expectancy at birth by sex (May 2024) and healthy life years at birth by sex (June 2024).