Summary

Key insights

Among the legacies of the Covid-19 crisis, we have – first and foremost – the surfacing of a renewed inflation regime. Signs of this trend emerged in 2021, with price rises not seen for decades across the world. This dynamic has been compounded by the Russia-Ukraine war, which has significantly hiked energy prices and exacerbated pre-existing supply-chain bottlenecks.

This has encouraged investors to broaden their investment landscape in an attempt to preserve their investments’ real value. In this respect, an obvious option has been to look at global real estate markets. Despite the Covid-19-driven economic shock, house prices have continued to rise in most developed markets (DM), as well as in some emerging markets (EM). The current situation differs across regions. Even so, the fact that prices are rising simultaneously in different countries raises the issue of a possible ‘common factor’ underpinning the increase. One possibility for a common factor is the major central banks’ (CB) monetary policy stimulus delivered during the Covid-19 crisis, coupled with strong demand both for societal – the pandemic has boosted demand for onefamily houses – and investment reasons, the latter being the desire to invest in real assets.

At the G10 level, the increase in house prices and household debt is exacerbating fears that real estate may become a source of macro financial vulnerability, similar to what happened during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), especially now that major CB are withdrawing their stimulus. In the United States, the recent rise in mortgage rates could depress household demand for housing and some borrowers will no longer be able to get a mortgage or will be deterred by the additional cost. However, the current situation looks less tense than during the pre-Lehman period and real estate should not be a source of systemic risk for several reasons:

- Despite the increase, growth in household lending remains far off its mid-2000s pace in most countries.

- Household debt seems to be less at risk than during the pre-Lehman period. In the United States, the average borrower profile is now far more solid than in the mid-2000s, when the excesses of subprime loans were regarded as the main cause of the subsequent crisis.

- Banking surveillance has been stepped up considerably over the past 15 years. In several large countries (including the United States, Germany and France), the vast majority of household debt is now at fixed rates, with limited exposure for indebted households to interest rate rises.

China’s real estate market is on a different cycle. In light of the recent troubles experienced by major domestic builders, the authorities aim to decouple the Chinese economy from the housing sector and cool down the speculative forces which drove prices to bubble levels. China has entered a new era of housing regulations, no longer using the sector as a countercyclical tool to boost the economy and we expect a contraction of sales at around 10-15% in 2022.

Investors have plenty of tools available when it comes to investing in real estate markets. They range from investing in physical real estate assets to more sophisticated financial tools backed by mortgages, to collateralised debt and loans obligations. An analysis of the risk-return profile of these tools shows positive returns since their inception date for every tool, with US non-agency securities generally yielding higher returns than those guaranteed by the government, translating into a higher risk premium. In terms of risk, publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs) appear as the most volatile tool due to their equity component. In any case, all tools appear to be options to complement a global diversified portfolio in an era of high inflation and rising rates.

The assessment of real estate macro dynamics and returns will be key to portfolio construction.

G10: higher rates could weigh on valuations but not derail markets

The Covid-19 crisis has accelerated the rise in residential real estate prices across DM, where they keep setting new all-time records:

- OECD figures point to a record – or near-record – pace in twelve-month nominal price increases in Q3 2021 (the latest available data), going back to at least the early 2010s in most large countries, the only exception being Italy.

- Nominal price levels hit all-time highs in Q3 2021 in most countries, with the pre-Lehman records having already been exceeded before the Covid-19 crisis. Among the countries where this was not the case, Spain is also currently approaching its pre-Lehman peak, although Italy and Japan remain far from their highs.

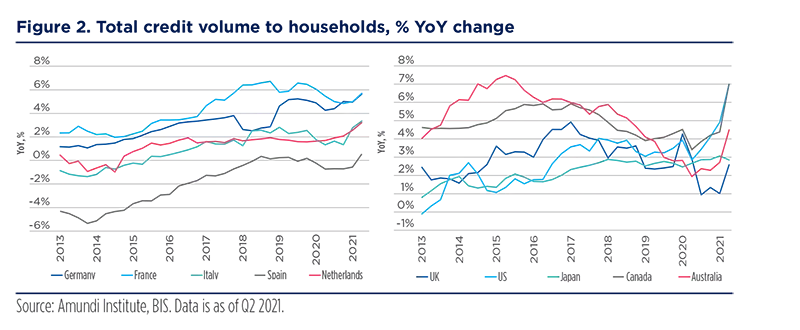

Household debt, consisting mostly of mortgages, has also been accelerating. Bank for International Settlements (BIS) figures as of Q2 2021 point to a record or near-record household debt rise within the post-GFC period across most DM, although far from their pre-GFC peak.

BIS figures point to a record or near-record household debt rise within the post-GFC period across most DM, although far from their pre-GFC peak.

The causes of this dual upward trend of house prices and household debt during the Covid-19 period can largely be attributed to the policy response to the pandemic:

- Public assistance to corporations (helping keep work contracts in place), generous short-hour work measures and social welfare payments helped preserve much of, or even increase in the United States’ case, household income in most countries. Meanwhile, the limited options for consumption during lockdowns led to a steep increase in household savings.

- Extensive non-conventional monetary policy measures sent mortgage lending rates to record lows.

- The development of smart working may also have raised households’ appetite for more living space, while the shutdown of construction sites during the Covid-19 period led to tighter new supply. However, these factors probably count less than the positive impact of incomes and interest rates mentioned above.

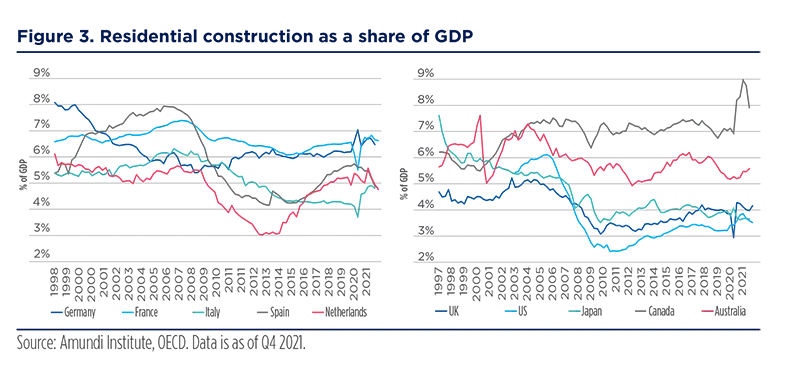

This increase in housing prices and household debt is exacerbating fears – already present before Covid-19 – that real estate may become a source of macro-financial vulnerability, similar to what happened during the 2008 GFC. Even so, the current situation looks less tense than during the pre-Lehman period. Firstly, residential investment-to-GDP ratios show that, just before the Covid-19 crisis, there were no clear excesses in construction, unlike the situation observed in Spain, Ireland and the United States during the pre-GFC period. Such excesses were significant factors in exacerbating the subsequent crises, via heavy job losses and bankruptcies in the real estate sector.

Despite the relatively fast recent increase, growth in household lending remains far from its mid-2000s pace in most countries. In the United States, it peaked at around 14.0% annually back then, compared to about 6.0% currently. In the Eurozone, the equivalent mid-2000s figure reached about 12.0% and over 20.0% in Spain. As of December 2021, it was only around 5.0% in Germany and France, where lending has been increasing the fastest among the four largest Eurozone countries. Household debt also seems to be less at risk than during the pre-GFC period:

- In the United States, the average borrower profile is now far more solid than in the mid-2000s, when the excesses of subprime loans were generally regarded as the main cause of the subsequent crisis1.

- Banking surveillance has been stepped up considerably in the past 15 years. In several large countries (including the United States, Germany and France), the vast majority of household debt is at fixed rates, with no direct exposure to a possible increase in interest rates for already indebted households.

Despite the relatively fast recent increase, growth in household lending is still far off its mid-2000s pace in most countries.

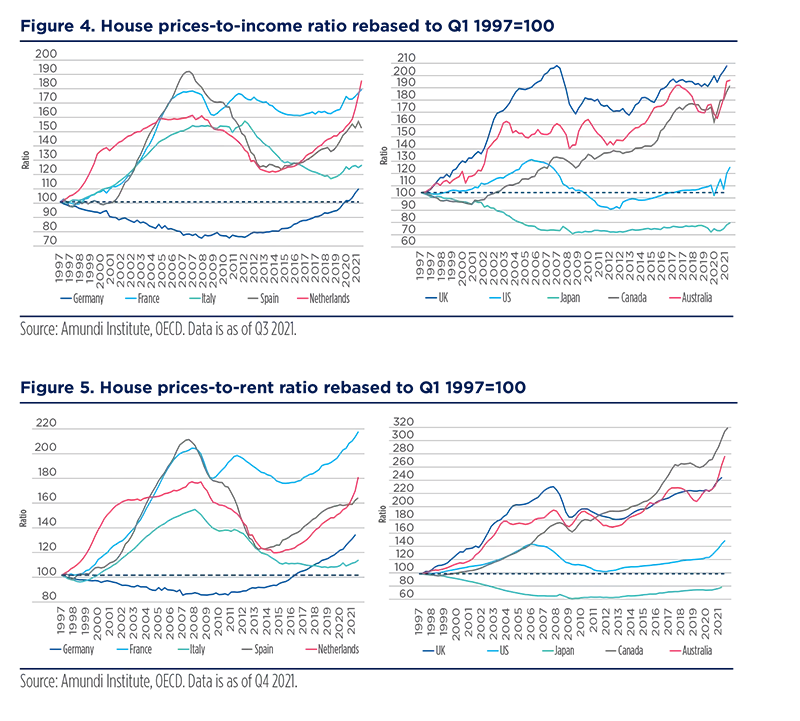

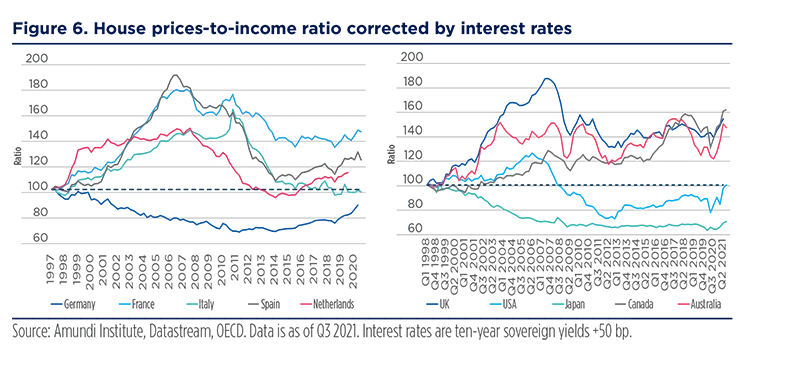

Most of the reason why some commonly used housing valuation indicators are very high seems to be a ‘simple’ adjustment to interest rates rather than excessive developments or behaviour related to the real estate sector itself. Like nominal prices, price-to-rent and price-to-income ratio valuation indicators have accelerated during the Covid-19 crisis, although price-to-income ratios remain significantly below their all-time highs in the United States, among other countries2 (see figure 4).

Most of the reason why some commonly used housing valuation indicators are very high seems to be a ‘simple’ adjustment to interest rates rather than excessive developments or behaviour related to the real estate sector.

However, these indicators do not reflect the impact of interest rates on buyer solvency and investor returns. Most – although not all – of these increases can be explained by an adjustment that, given the decline in interest rates, ultimately keeps purchasing power unchanged. In other words, in many countries, price increases have been moderate once adjusted for changes in income and interest rates, at least until mid-2021 (see figure 6).

This is also the message sent out by current purchasing power indices, such as the US Housing Affordability Index. Despite the steep increase in nominal prices, in December 2021 this indicator was at a similar level to where it was in early 2019, lower than at the peak of the Covid-19 crisis, when incomes were very high and interest rates very low, but far better than during the pre-GFC years (see figure 7). This does not apply to Germany, Canada and Australia, where prices – when adjusted for income and interest rates – are at or near highs of at least 15 years, after having taken different paths to get there. Such measures of affordability do not yet factor in the acceleration in long-term interest rates which took place in Q1 2022: absent a simultaneous consolidation in house prices, the next prints of affordability indicators could show that households’ real estate purchasing power is starting to deteriorate in many countries.

In many countries, price increases are moderate once adjusted for changes in incomes and interest rates.

The US housing market is behaving abnormally and house prices are increasingly unjustified by fundamentals. As such, it is clear that the recent surge in mortgage rates3 will depress household demand for housing. Some borrowers will no longer be able to obtain a mortgage or will be deterred by the additional cost. While acknowledging a strong price acceleration since 2020 – and the first signs of a bubble – the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas stressed in a recent note4 that the situation has nothing to do with the GFC. Household balance sheets are stronger and there is no evidence of excessive debt.

The predominant role of interest rates in high valuations has important implications in terms of qualifying risks, which are primarily tied to the possibility of rates moving up further. Describing the current situation as a ‘real estate bubble’ assumes, above all, that one sees the current level of interest rates as still abnormally low. The role of exaggerated expectations in terms of housing prices and housing demand, that have been an important factor in the build-up of many past real-estate bubbles, seems less instructive here. Current house prices may be at risk, yet first and foremost because a continuing rise in interest rates would make them unsustainable. Such a risk applies in the case of higher rates following further CB tightening expectations (indeed, for CB, avoiding excessive real estate valuations can be one more reason to tighten, although with prudence), as well as in the case of a deterioration of financial conditions that would be unwanted by CB.

While a drop in real estate prices would have negative repercussions on the rest of the economy, even a steep one would not be the powerful crisis accelerator that it was during the Lehman crisis.

Conversely, it is harder to foresee a sharp correction in real estate prices for other reasons, such as the sudden realisation by economic players that the sector is in a bubble-like situation due to ‘animal spirits’ or excessive investment. A steep rise in housing supply that would drive prices sharply lower also seems unlikely. It is true that there could always be an economic shock from another cause that would reduce household incomes and – if not fully offset by lower interest rates – nominal housing purchasing power with negative consequences on prices.

However, while a fall in real estate prices would have negative repercussions on the rest of the economy, even a steep one would not be the powerful crisis accelerator that it was during the GFC. The impact of lower house prices would probably be detrimental to household consumption due to wealth effects, albeit more so in the United States and the United Kingdom than in the Eurozone, where these effects are less proven. It could also undermine household borrowing for consumption in countries where real estate can be used as collateral. Yet, for the reasons laid out above, the fallout on the labour market – through job destruction in construction – and in the financial sector – bankruptcies by property developers and householders – would probably be more moderate than in the late 2000s. Nonetheless, the risk exists that the current increase in house prices could lead to expectations of further rises and, within a few months or years, to irrational exuberance driving up valuations to levels that could no longer be explained by income or interest rates. Residential real estate would then be in a bubble, with more severe consequences in the event of a later correction. While we are not there yet, the possibility that such a situation could occur must be monitored.

A final point worth mentioning is the special case of large ‘globalised’ cities, in which the continuous decline in purchasing power has been undeniable in pre-Covid-19 years. These are localised configurations – although large in number and common to many countries – that are distinct from the housing prices used in figuring national averages. Affordability issues in large cities are perceived as politically and socially sensitive and are often linked to the issue of inequality (across socio-professional groups, generations or regions). It is also likely that the excessive price rises in these large cities (on top of what can be explained by income levels and interest rates) are due more to shifts in local supply-demand balances, which, in turn, have ‘real’ causes (e.g., sectoral labour market and wage trends and restrictive building codes) than to overdone ‘bubble-like’ expectations. Until the Covid-19 crisis, abundant demand and scarce supply in these markets seemed likely to persist, supporting prices. In some ways (e.g., smart working, which, in theory, should boost demand for less central areas), Covid-19’s long-term consequences could help ease such pressure. However, while some recent figures may indeed point to this (e.g., relative prices of more sparsely populated areas rising versus globalised cities), they are not enough, as of now, to confirm that the attraction of large cities will fade for good, especially as the Covid-19 crisis is not over yet.

Affordability issues in large cities are clearly perceived as politically and socially sensitive and are often linked to the issue of inequality.

What should – or could – central banks do about a real estate boom?

Rising real estate prices driven by a credit boom have been harmful in the past. In 2009, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff found that, over a long period, collapses in real estate prices (both residential and commercial) are one of the main causes of financial crises. In many cases, such collapses occur after real estate bubbles that seem to be linked to excessive credit. When the bubbles burst, both the financial sector and the real economy are hit hard. Monetary policy’s role in preventing real estate bubbles is a controversial issue. In theory, it is believed that suitable macro-prudential regulation should free CB from having to react to real estate prices. Discretionary macro-prudential policies, which toughen terms of access to credit on a selective basis, play an important role in preventing or mitigating real estate bubbles. At the same time, CB must ensure that their monetary policies do not exacerbate household debt. As such, keeping an eye on rising real estate prices is an important component of any risk management approach. Low short-term interest rates often lead to looser lending terms and greater risk-taking by banks. This effect is amplified when interest rates stay low for an extended period of time. The loosening of credit conditions is exacerbated by the use of securitisation, which varies in intensity from country to country.

Wherever real estate markets are highly diverse (e.g., in Eurozone or the United States), taking a tougher line on monetary policy to rein in pricing pressure is often unsuited and possibly counterproductive.

In economies where a large share of consumers are subject to credit restrictions, a steep rise in real estate prices can have pronounced effects on consumption, in the form of the wealth effect. Leverage tends to be very high in the real estate sector and residential real estate is both the main asset and the main liability for many households (this is not the case for stock holdings). As discussed above, there were many factors involved in the global spike of real estate prices, including disposable income, interest rates and bank credit. However, there is general agreement that the declining trend of global real interest rates was among the main drivers of higher housing prices during the 2000s. Now that DM CB are withdrawing the Covid-19-era policy stimulus and embarking in rate hikes, there is a medium-to-long-term risk of higher real interest rates, posing problems for countries where homes purchases have been financed by debt. Finally, the ample liquidity still in the system could also feed into higher housing prices. An official rate hike is not a cure-all solution. This may be desirable in economies with a high degree of homogeneity, e.g., smaller countries such as Sweden or mid-sized ones like the United Kingdom. However, wherever real estate markets are highly diverse (e.g., in Eurozone or the United States), taking a tougher line on monetary policy to rein in house price pressures is often unsuitable and possibly counterproductive.

In summary, CB need to pay attention to the huge pile of public and private debt that has been accumulated during successive crises. A sudden toughening in financial conditions would have more drawbacks than advantages. Real and financial assets should remain relatively attractive as long as real interest rates remain negative, and they are likely to remain so for a long time, especially in the Eurozone. The United States will have to be watched closely: the Fed started its rate-hiking cycle in March and intends to raise rates aggressively in the first half of the year and then reduce the size of its balance sheet. The rise in nominal interest rates should contribute to the slowdown in residential real estate.

Real and financial assets will remain relatively attractive as long as real interest rates remain negative.

China real estate: a regime change

China’s real estate trends deserve a standalone analysis, given their specific features and relevance in shaping financial market trends. The real estate sector is a key pillar of the Chinese economy, accounting for some 30% of GDP, including upstream and downstream sectors. The sector generates almost 50% of fiscal revenue for the local government and it is a store of wealth for Chinese people. The sector is systemically important for the country’s stability and its economy and has been in consolidation mode since the introduction of the Three Red Line policies in 2020, whose key goals are reducing financial leverage and preventing the market from overheating. The operating environment for real estate companies was already difficult based on a confluence of factors:

- Slowdown of the overall economy;

- Margin pressures triggered by cost inflation and weaker selling prices;

- Funding pressures for developers;

- Increased mortgage costs for consumers; and

- A restrictive policy stance.

Since H2 2021, the deterioration in fundamentals of China’s real estate market has accelerated. Housing sales fell 22.1%YoY in January-February 2022, after dropping 18.7% YoY in Q4 and 14.1% YoY in Q3 2021, driving up inventories. The volume of land transactions contracted by 42.3%YoY in January-February against a fall of 25.3% YoY in Q4. Besides, property investments and construction decelerated, weighing on cement, rebar (reinforcing steel) and glass production.

Policy changes are under way

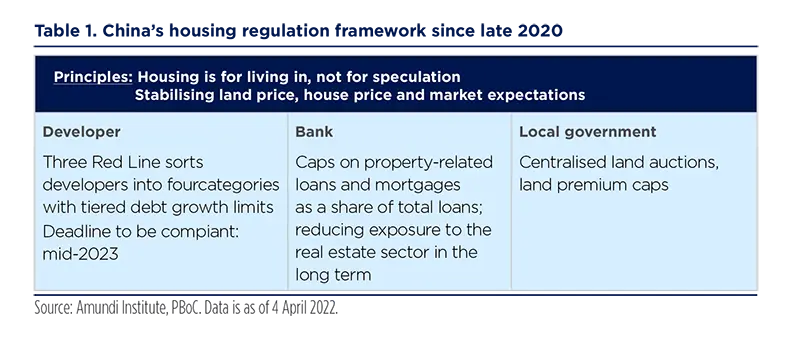

Financial regulators have stepped in since October 2021 to accelerate loan disbursement and address mortgage approvals. Governments have given developers more access to pre-sale funds in escrow accounts. As credit events begun to hurt household demand, more local governments joined the easing camp, loosening housing purchase restrictions and lowering down payment ratios. However, we think the leadership will unwaveringly decouple the Chinese economy from the housing sector in the long run. In the People’s Bank of China’s (PBoC) own words, “while forestalling and defusing ‘Gray Rhino’ risks in the real estate sector and achieving the stable and healthy development of the real estate market, it also drives the structural transformation and high-quality development of China’s economy, and lowers the overall financial risks.” Adhering to the principle that housing is for living in and not for speculation, China has entered a new era of housing regulations, no longer using the sector as a countercyclical tool to boost the economy. The current policy framework regulates all key stakeholders. It will be too complacent for markets to expect an abolishment of the Three Red Lines policies or housing loan caps in the banking sector, despite the increasing cases of restructuring among private developers.

China’s real estate sector has been in consolidation mode since the introduction of the Three Red Line policies in 2020. Key policy objectives were to reduce financial leverage and prevent the market itself from overheating.

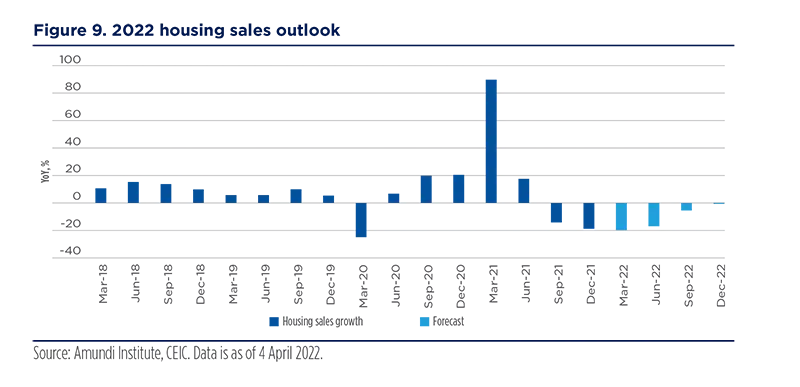

Mortgage quotas are likely to remain a constraint on housing sales in the medium term, although banks were asked to accelerate mortgage approvals and not withdraw credit lines from developers or home buyers. Reducing exposure to the real estate sector is deemed key to meeting the new development strategy. A gradual reduction in the share of mortgages in the overall bank loan portfolio is the most likely scenario. Meanwhile, the structural demand peak has not been met yet. Even though we expect the population to peak in 2026, social changes including urbanisation, smaller household size and a likely increase in the divorce rate should drive housing demand up5. Nevertheless, cyclical demand has cooled notably amid increasing credit events and weakening macro momentum, especially in smaller cities. In PBoC’s March consumer survey, the percentage of residents intending to buy a home and those believing prices will increase was at a cyclical low. We expect housing sales to contract by 10-15% in 2022 after a gain of 4.8% in 2021. We believe policies have turned and are heading in a more favourable direction, to help ease liquidity pressures for developers. That said, it will take time for fundamentals to find their bottom. Base effects will play a significant role in 2022, given the sector’s buoyant growth in early 2021. We expect China’s housing market to stabilise in H2 2022. Assuming deleveraging continues at a gradual pace, the home sales contraction should narrow in 2023 and is likely to turn positive in 2024.

We expect China’s Figure 9. 2022 housing sales outlook housing market to stabilise in H2 2022. Assuming deleveraging continues at a gradual pace, the home sales contraction should narrow in 2023 and is likely to turn positive in 2024.

Investment tools and styles to suit real estate

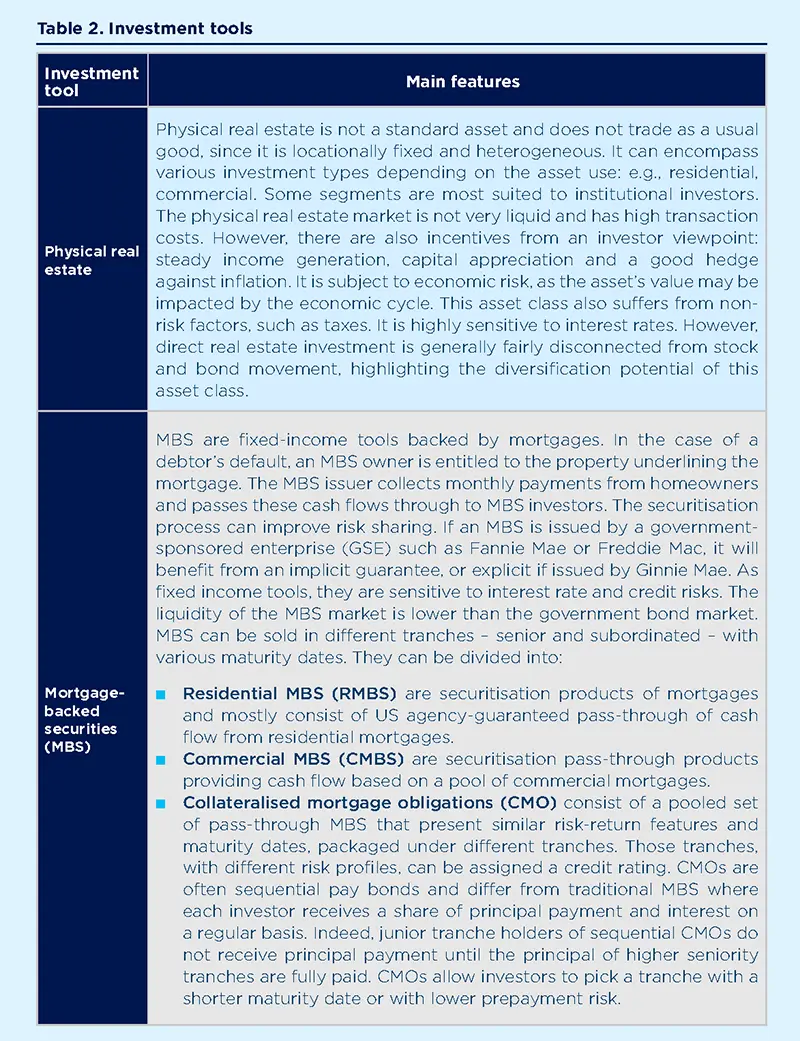

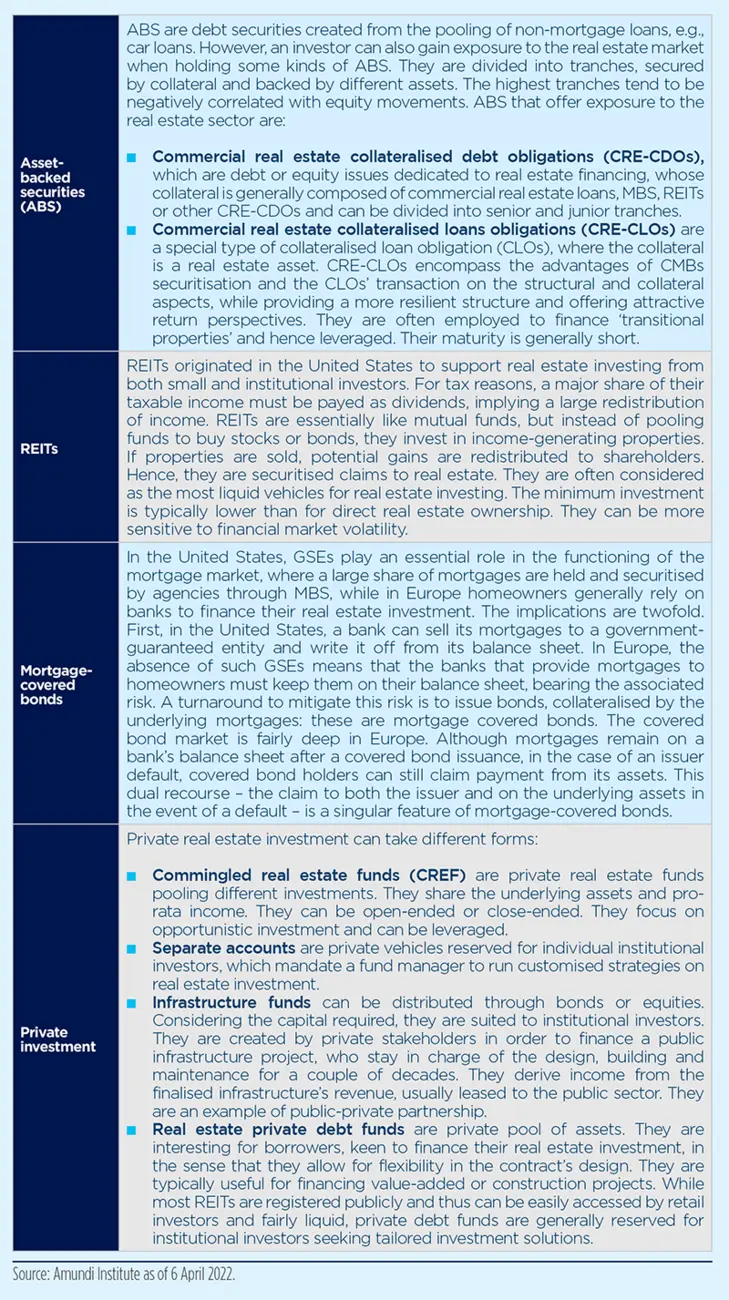

As discussed, real estate has attracted a lot of investment over recent decades, with investors turning to this market to complement traditional asset classes in their search for diversification benefits, appealing risk-adjusted returns and as a hedge against inflation. However, not all real estate investments are alike and there are plenty of tools to invest in real estate, both direct and indirect. Investment styles can also differ significantly.

Investment tools

Table 2 shows the main investment tools available to investors.

Investment strategies

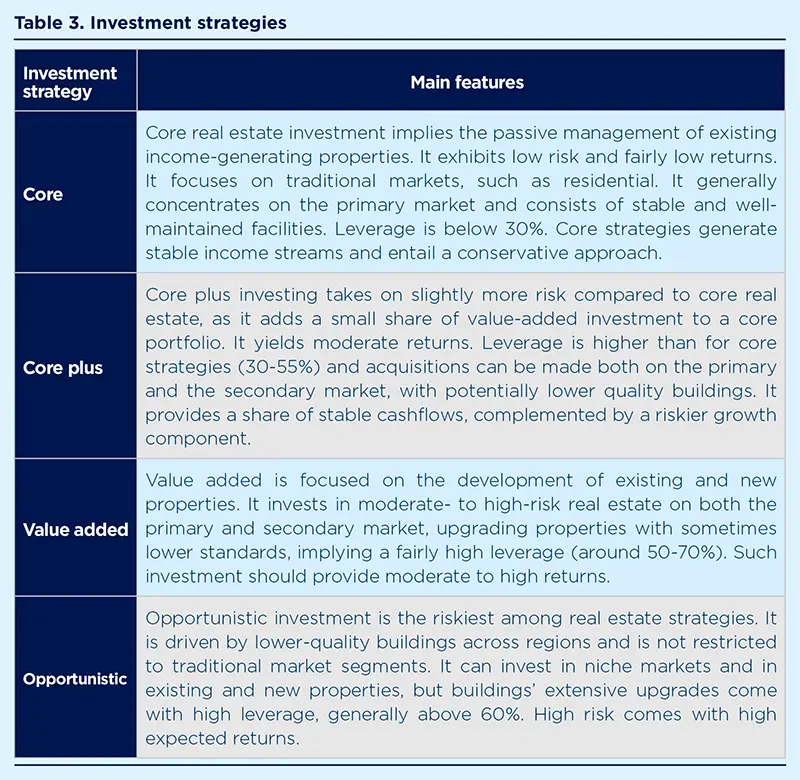

Not all real estate investment styles are alike. Table 3 shows the main investment strategies.

Source: Amundi Institute and Preqin glossaryas of 6 April 2022.

Risk and return

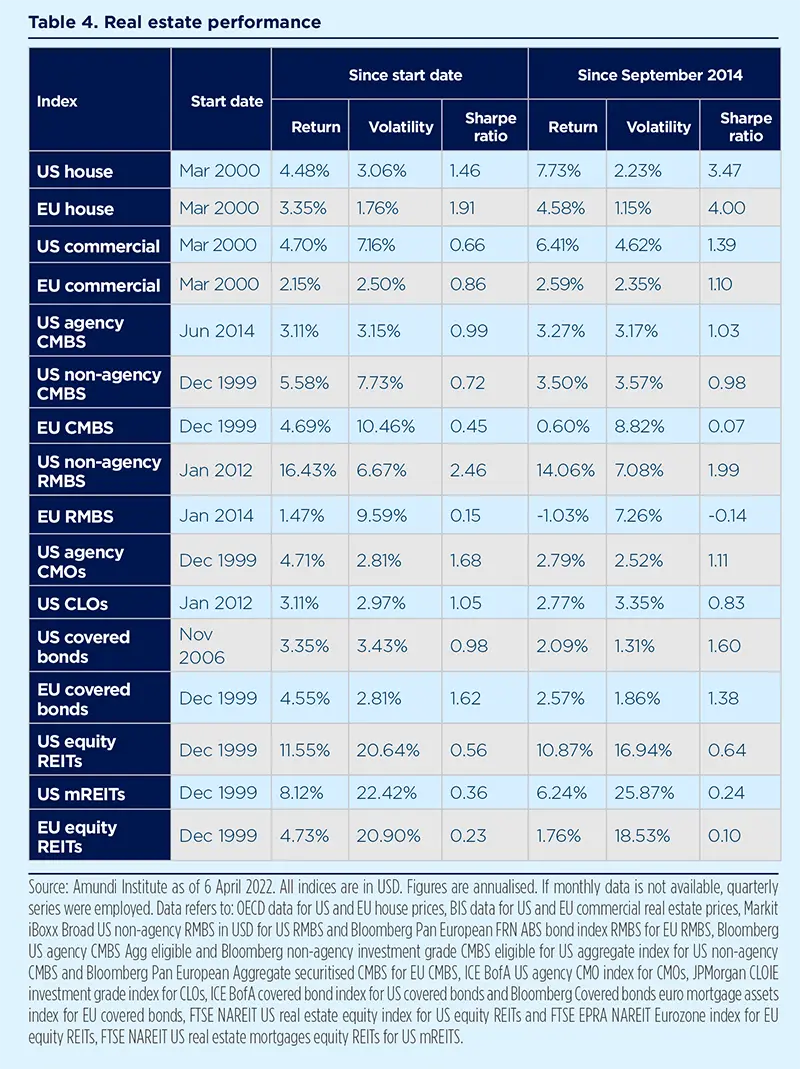

To appraise and compare the co-movements risk and return potential of the above asset classes, we analysed indices and their performance. While for physical real estate we only hold quarterly times series, for other vehicles we could retrieve monthly data. With reference to the US market, real estate has been on a broadly upward trend over the past two decades. However, depending on the asset class, performance may have taken a few severe hits along the road. Following the GFC, mortgage REIT investments (mREITs) were shattered. Mortgage-covered bonds, non-agency CMBS, and equity REITs were also not immune. More recently, mREITs experienced another performance dip amid the Covid-19 outbreak, while house prices held up well. On the volatility front, we observe that, in Europe, direct investment into property also yields the most stable returns. The performance of European REITs before the GFC was particularly striking. Direct investment, as well as mortgage covered bonds, proved more resilient than other vehicles when the pandemic hit. Over the past two decades, the RMBS we analysed have been particularly volatile. On table 4 we estimate the risk-return properties for different real estate investments.

US non-agency RMBS posted the highest return, followed by US equity REITs

Most indices showed positive returns since 2014 and all posted positive figures since the respective start date of our analysis. We also calculated the risk-return metrics over the same reference period, starting in September 2014. In both cases, US non-agency RMBS posted the highest return, followed by US equity REITs. Generally, non-agency securities yield higher returns than those guaranteed by the government, which translates into a higher risk premium. In terms of risk, publicly traded REITs appear as the most volatile tool, due to their equity component. Direct physical investments show some of the lowest volatility figures, although US commercial real estate is slightly more volatile than other indices. US CMOs, CLOs (for the longest sample only), and the covered market follow. In terms of risk-adjusted returns, US non-agency RMBS, EU housing, EU covered bonds and US agency CMOs emerge as the most attractive vehicles for the longest sample period, although they present very different risk profiles. When focusing on the most recent market dynamics, EU and US housing show the highest risk-adjusted returns. However, physical real estate investment is not a liquid option. Of the investable liquid universe, US non-agency RMBS, CMOs and CMBS, as well the covered market (both EU and in US), stand out as the most attractive instruments. EU CMBS and RMBS were among the lowest risk-adjusted returns, close to US mREITs or EU equity REITs. This result on EU MBS is insightful, since these instruments are true US-style products translated in Europe. This non-native asset class appears to lag in the EU.

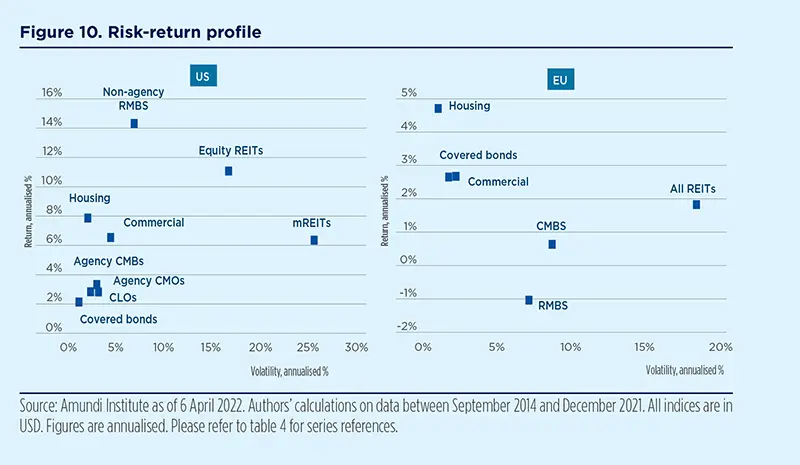

Figure 10 assesses the risk-return profile of different US real estate assets since September 2014. Non-agency RMBS clearly outperforms. We also noticed how the least liquid part of the market, namely physical real estate, presents strong adjusted-returns figures. Still, interesting opportunities exist in the liquid space: equity REITs are particularly appealing in terms of returns. In contrast, mREITs are the riskiest tools, not off-set in terms of return. Finally, CMBS, CLOs, CMOs and covered bonds exhibit similar profiles, with modest performance compared to other tools and low risk. We can draw similar conclusions for Europe: physical real estate yields the highest returns. The least liquid segment of the market outperformed again. However, covered bonds were the most attractive assets in Europe in terms of risk-adjusted returns. Non-native instruments, such as RMBS and CMBS, are less attractive in terms of returns and are more volatile. Finally, EU REITs have not performed as strongly as their US counterparts in recent years. In addition, their volatility is high, undermining their attractiveness in Europe.

Of the investable liquid universe, US non-agency RMBS, CMOs and CMBS, as well the covered market (both EU and in US), stand out as the most attractive instruments.

_________________________

1 This factor is highlighted regularly in the Federal Reserve’s Financial Stability Reports.

2 These metrics are used by the ECB, among other factors, as valuation indicators and currently point to overvaluation in most Eurozone countries.

3 On 7 April 2022 Freddie Mac announced that “mortgage rates have increased 1.5pp over the last three months (30-year fixed mortgage rate at 4.7%), the fastest three-month rise since May 1994”. As a result, “the monthly payment for those looking to buy a home has risen by at least 20% over one year”.

4 “Real-Time Market Monitoring Finds Signs of Brewing U.S. Housing Bubble”, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 29 March 2022

5 Mou, X., Li, X. & Dong, J., The Impact of Population Aging on Housing Demand in China Based on System Dynamics., J Syst Sci Complex, 34, 351–380 (2021).

Definitions

- ABS: Asset-backed securities. These are financial securities such as bonds, which are collateralised by a pool of assets, possibly including loans, leases, credit card debt, royalties or receivables.

- Agency mortgage-backed security: Agency MBS are issued by one of three agencies: Government National Mortgage Association (known as GNMA or Ginnie Mae), Federal National Mortgage (FNMA or Fannie Mae), and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp. (Freddie Mac). Securities issued by any of these three agencies are referred to as agency MBS.

- Asset purchase programme: A type of monetary policy wherein central banks purchase securities from the market to increase money supply and encourage lending and investment.

- Basis points: One basis point is a unit of measure equal to one one-hundredth of one percentage point (0.01%).

- Beta: Beta is a risk measure related to market volatility, with 1 being equal to market volatility and less than 1 being less volatile than the market.

- CLO: Collateralised loan obligation. It is a single security backed by a pool of debt. CLOs are often backed by corporate loans with low credit ratings or loans taken out by private equity firms to conduct leveraged buyouts.

- Closed-ended fund: In these funds, there is no internal mechanism for investors to redeem their subscriptions. Investors’ subscriptions are tied-up for the lifetime of the fund unless investors can find a buyer for their shares on the secondary market.

- Core plus real estate investment strategy: ‘Core plus’ is synonymous with ‘growth and income’ in the stock market and is associated with a low to moderate risk profile. Core plus property owners typically have the ability to increase cash flows through light property improvements, management efficiencies or by increasing the quality of the tenants. Similar to core properties, these properties tend to be of high quality and well occupied.

- Core real estate investment strategy: ‘Core’ is synonymous with ‘income’ in the stock market. Core property investors are conservative investors looking to generate stable income with very low risk. Core properties require very little handholding by their owners and are typically acquired and held as an alternative to bonds.

- Correlation: The degree of association between two or more variables; in finance, it is the degree to which assets or asset class prices have moved in relation to each other. Correlation is expressed by a correlation coefficient that ranges from -1 (always move in opposite direction) through 0 (absolutely independent) to 1 (always move in the same direction).

- Open-ended funds: In these funds, investors have the choice of whether to partially or completely redeem their subscription on each redemption day, subject to the redemption terms specified in the fund’s offering document.

- Opportunistic real estate investments: Opportunistic is the riskiest of all real estate investment strategies. It is synonymous with ‘growth’ in the stock market. Opportunistic investors take on the most complicated projects and may not see a return on their investment for three or more years. Opportunistic properties often have little to no cash flow at acquisition but have the potential to produce a large amount of cash flow once the value has been added.

- Quantitative easing (QE): QE is a monetary policy instrument used by central banks to stimulate the economy by buying financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions.

- REIT: A real estate investment trust is a company owning and operating real estate which generates income. Most REITs specialise in a specific real estate sector, focusing their time, energy, and funding on that particular segment of the entire real estate horizon.

- RMBS: Residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) are a debt-based security backed by the interest paid on loans for residences. The risk is mitigated by pooling many such loans to minimise the risk of an individual default.

- Value-add real estate investments: ‘Value-add’ is synonymous with ‘growth’ in the stock market and is associated with moderate to high risk. Value-add properties often have little to no cash flow at acquisition but have the potential to produce a large cash flow once the value has been added.