Summary

In order to better understand geopolitical trends, Amundi has developed the Geopolitical Sentiment Tracker (GST). The tool aims to inform the investment process: it includes a variety of datapoints allowing investors and researchers to better understand and be alerted to rising risks. It also allows our teams to identify opportunities.

This paper focuses on the GST’s first capability: risk identification. To showcase what it can do, we outline the current geopolitical context, and how the tracker informs our analysis.

We expect geopolitical risk will remain elevated for the next several years as a result of the growing number of actors involved, the tectonic geopolitical and technological shifts underway, and deteriorating bilateral relations.

To get a better assessment of where the risk is emanating from, the Geopolitical Sentiment Tracker provides insights into these risks and alerts us to changes.

The 2020s will likely see growing levels of geopolitical risk

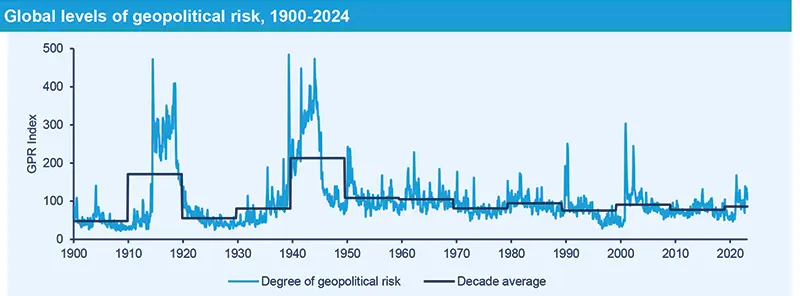

According to the Geopolitical Risk Historical Index1, which measures geopolitical risk since the early 1900s, the 2020s so far seem to rank ‘middle of the pack’ when compared to periods in history facing high or low geopolitical risk.

Interestingly, the level of risk calculated for the first few years of the 2020s is comparable to that seen throughout the duration of the cold war, roughly from the 1950s to the 1990s. A period that, characterised by the rivalry between two super powers is, to some extent, comparable to today’s environment shaped by US-China tensions.

Source: Amundi Investment Institute on Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), and Dario Caldara and Matteo Iacovello Geopolitical Risk Indicator (GPR) – see data here1.

More countries drive risk

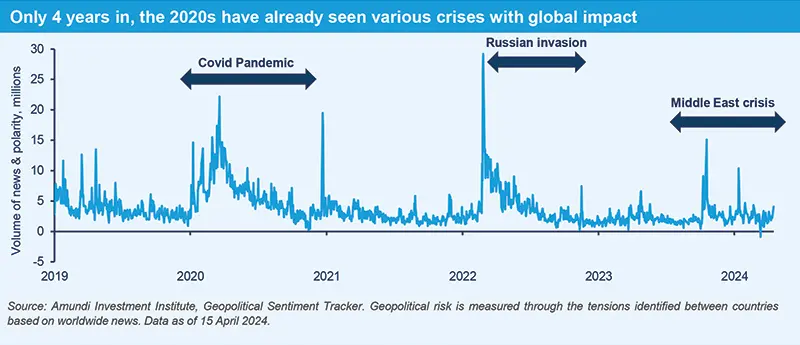

Delving deeper into Amundi’s new Geopolitical Sentiment Tracker, we can deduct from the data that the 2020s are likely to remain a period of elevated geopolitical risk.

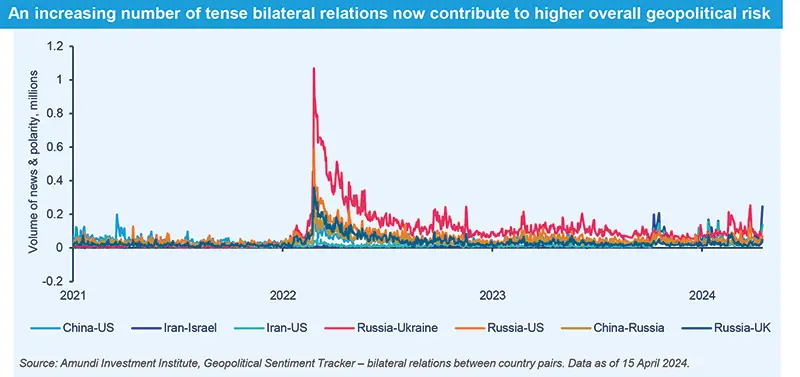

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, more countries are contributing to driving geopolitical risk. Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel and the subsequent involvement of many different (and also new) actors in the ensuing tensions in the Middle East further accentuate these dynamics.

Of course, today’s tensions are a result of the developments of prior decades. For example, 9/11 and the Great Financial Crisis laid the foundations for many of the political realities we see today in the Middle East and within Western democracies.

However, when we zoom into the 2020s, the impression that emerges is that the number of crises with global impact, and the pace at which they occur, are accelerating: the Covid pandemic lead to the break-down of global trade ties; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused major ruptures between traditional allies; the Middle East crisis is threatening to draw Iran, Israel and the United States into a bigger war. Some have coined today’s rapid succession of major negative developments a ‘polycrisis’.

More scope for tensions, protectionism, economic and ‘hot’ war

We have established that today’s geopolitical tensions involve a greater number of actors. The more tensions persist between countries on different issues, the more difficult it will be to de-escalate and find common ground. Today’s geopolitical trend of power ‘realignment’, which we have elaborated on in a previous paper, contributes to this risk.

The realignment underway is a result of the geopolitical shifts occurring since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and since China stepped more confidently onto the global stage as a competitor and challenger to the US. ‘Middle powers’ have refused to take sides and instead are making the most of the current context to improve their negotiating position and obtain the maximum benefit for their own strategic, economic and political interests. India, for example, is signing new agreements with the US, while maintaining its ties to Russia as it sees no need and feels no pressure to take sides.

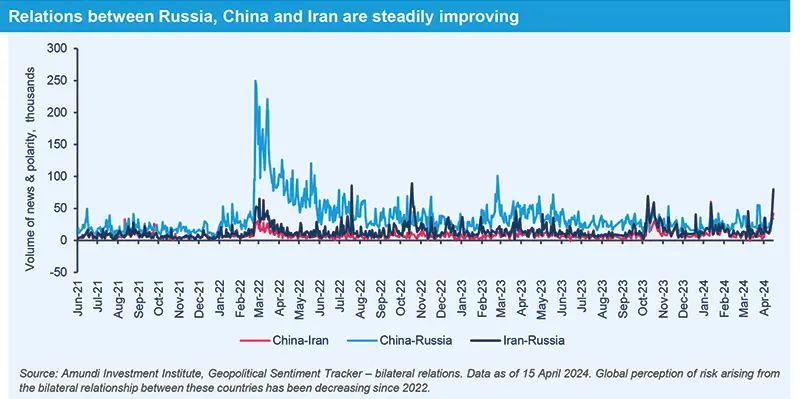

As tensions rise and common objectives are identified, new and unlikely partnerships also start to emerge. Russia’s military collaboration with Iran and North Korea are notable examples. These relationships are simultaneously supporting Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine, North Korea’s goals in the Korean peninsula, and Iran’s efforts to destabilise Israel and the US in the Middle East. These new dynamics are growing into significant new security threats for the US, which will be difficult to address.

While some middle powers benefit from the realignment, the influence the US and EU yield over other countries is being challenged.

The US will continue to respond with growing protectionism and an ‘America First’ strategy, no matter who sits in the White House, even though a second Donald Trump term would likely be more disruptive for existing US allies. The European Union will have no choice but to respond in kind after having seen an exodus of industrial firms drawn to the US by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). China and others will also react accordingly. All countries will use the levers they have and this means that natural resources will be used more readily for political advantage, as we have already seen with some rare earths and natural gas. As hostilities grow, so will export controls and sanctions.

All of these measures will see the prevalence of economic warfare rise, and this increases the risk of ‘hot’ war.

The threat posed by rapidly growing and more sophisticated misinformation, which Artificial Intelligence (AI) is certain to accelerate, adds another dimension, as do the negative consequences of climate change.

In sum, the geopolitical realignment is creating more complexity and more tension in many different directions.

Geopolitical risk is mainly driven by worsening bilateral relations

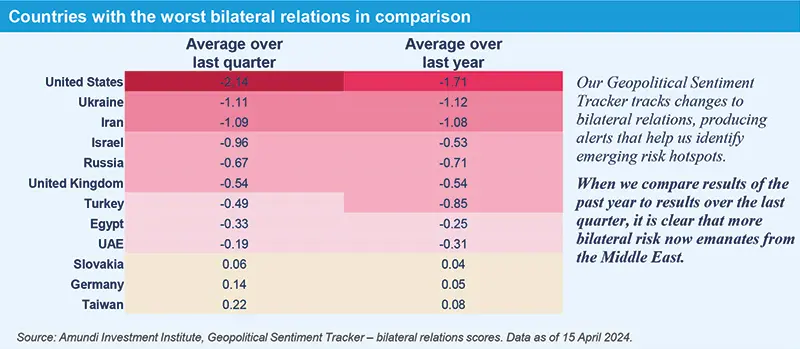

Both quantitative and qualitative analysis shows that geopolitical risk is mainly driven by relations between two countries. It is therefore important to track these bilateral relations. Below we outline our views on the likely trajectory of the bilateral relations we consider most critical for geopolitical risk for the foreseeable future:

We see growing risk for the US-China relationship that we define as a Great Power Competition on a path of ‘controlled, steady, downward decline’ for at least the next five years.

The electoral outcome in Taiwan, which earlier this year cemented a China-hawkish government, adds risk to the USChina relationship. The US election, in which both sides will campaign on the basis of being hawkish towards China, adds further tensions.

Faster than expected tech advances in China will accelerate the US clamping down on China’s technological development, irrespective of who ends up in the White House.

A Trump presidency would likely exacerbate trade tensions with China given that his administration would likely seek to divorce China from the US at a faster rate and more holistically than the Biden administration. The latter remains mostly focused on high tech sectors, such as semiconductors, AI and quantum computing – a list that will likely expand soon. As a result, we expect the next US administration to preside over worsening US-China relations.

Despite this, we expect both sides to exercise caution at the rate and pace of decline given that too much is at stake for both economies. Hence, we expect the worsening of ties to be controlled.

With regards to relations between China and Taiwan, for 2024 we see higher risks of a ‘middle road escalation’ which would greatly concern markets. We also see growing risks in the South China Sea more broadly.

With regards to relations between China and Taiwan, for 2024 we see higher risks of ‘middle road’ escalations such as a temporary blockade of the island, which would greatly concern markets. We also see growing risks in the South China Sea. These risks grow in line with US-China tensions, China’s domestic economic challenges, and the number of geopolitical hotspots requiring US involvement.

While a military attempt for China to take Taiwan is not our base case, a forced unification should not be underestimated. Taiwan’s ability to defend from such an attempt is low, and so is domestic confidence in the United States’ commitment to intervene on behalf of Taiwan. The more geopolitical hotspots involve the US militarily, the more of an opportunity for China to ‘act’ on Taiwan and push its interests in the South China Sea more assertively. There are many ways China can escalate from the current level, for example by implementing customs checks on ships, hiking insurance costs and adding political risk and uncertainty to the detriment of Taiwan.

We also see higher risks emanating from the war in Ukraine. The most likely scenario for 2024 is a continuation of the fighting, with Russia likely trying to gain more territory as the US election approaches. While 2024 will likely be a difficult year for Ukraine, 2025 could look very different.

Fears over Europe’s ability to protect itself from possible future Russian aggression will only grow alongside concerns over NATO protection from the US, leading European countries to accelerate their defence build-up, which in turn increases the risk of the war escalating beyond Ukraine.

Even in the most benign scenario of a ceasefire, Russia will most likely continue to be seen as a threat and a hostile actor within Europe for the next several years.

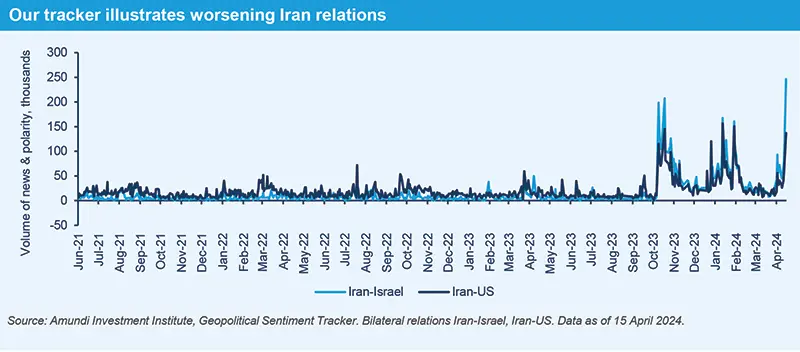

In the Middle East, there are many serious medium to longer term risks emanating from the political situation within Israel, a possible war between Lebanon and Israel, and a potential escalation between Israel and Iran.

Whatever the outcome of the Hamas-Israel war in the short-term, over the longer-term Israel will continue to face existential threats as a result of the forces unleashed since October 7th. The threat Iran poses to the US, following its role in supporting Russia and destabilising US positions in the region, has also grown significantly. Advancement of its nuclear capabilities adds another dimension of risk, meaning Iran is a growing threat that the US and Israel may soon feel the need to have to deal with.

Another geopolitical hotspot emerging with new force is the risk posed by North Korea. There are growing concerns that North Korea may decide to start a war against the South or plan a Hamas-style attack. There are various reasons for the notion that something has fundamentally changed from the usual way North Korea operates. Kim Jong Un’s rhetoric has changed, and there is evidence that Russia has received ammunition and weapons from North Korea, while North Korea is receiving ‘something’ from Russia, that could be food as well as more sophisticated technology. North Korea’s military capabilities seem to have improved.

There are two interpretations for North Korea’s more hostile behaviour. Kim Jong Un may have concluded that he has reached the end of the road in trying to improve relations with the US, and the only way to improve North Korea’s economic situation is to take the South to war. An alternative interpretation is that Kim is seeking to increase his negotiating power ahead of US elections in the hope that a return of Trump will open the door to negotiations to achieve sanctions relief, acceptance as nuclear power, and the removal of US troops from the Korean peninsula.

In any case, it is likely that North Korea will pose a growing risk, also because the new Russia-North Korea alliance gives the latter greater independence from China, and poses a new threat to the US given than Pyongyang’s worldview is ‘bought into’ the narrative of a weaking of the US.

The geopolitical sentiment tracker – What it does

Above, we have explained why it is important to understand bilateral relations in real time. Of course, a country’s risk exposure is driven by several components, all of which have to be tracked to obtain a holistic assessment.

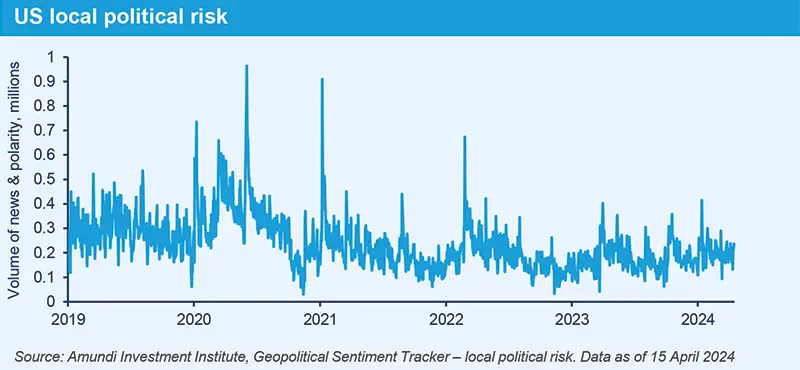

We also assess a country’s local political stability based on real-time data that alerts us to changes in the domestic political atmosphere.

For example, when we look at the US, our index illustrates big spikes for local political risk after the killing of George Floyd in May 2020 and the storming of the Capitol in January 2021:

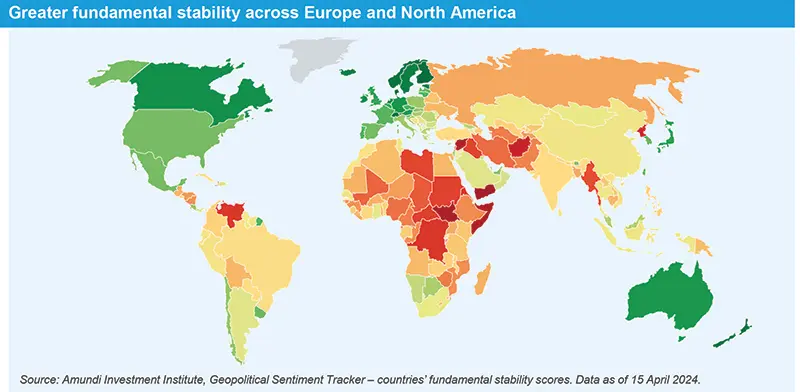

We also assess ‘fundamental’ political stability, based on low-frequency data from international organisations, to better understand the underlying ‘health’ of a country’s political and legal institutions, security infrastructure, human rights, press freedom, etc.

When looking at ‘fundamental’ stability, many parts of Europe and North America rank better because of their institutions, despite the many geopolitical risks they face.

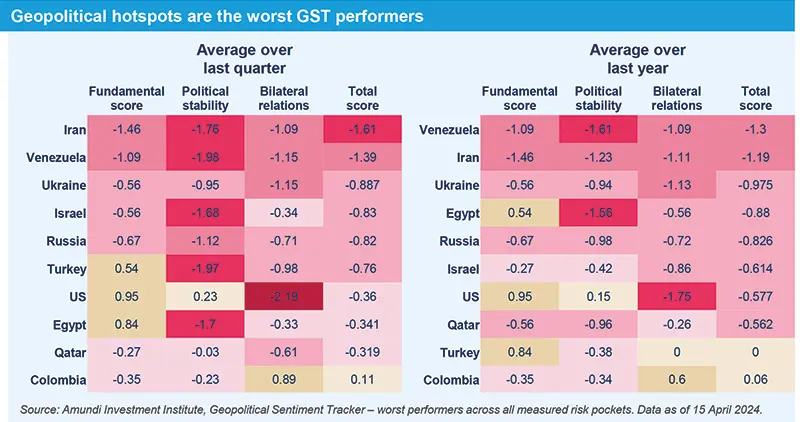

Lastly, we add all of these components – local risk, bilateral relations risk, fundamental stability - into an overall ranking that alerts us when a country moves up or down the scale. The world’s geopolitical hotspots are the worst performers in our Geopolitical Sentiment Tracker.

Methodology

Our Geopolitical Sentiment Tracker contains the sub-indices and datasets below. We are implementing these datasets into Amundi’s economic and risk models which inform our investment process.

- Fundamental Stability Index: The fundamental score ranks all countries based on data from public sources (such as the World Bank, UN, etc.). It assesses a country's ‘fundamental’ stability by ranking quality of governance, press freedom, levels of conflict and human development, etc.

- Local Political Stability Index:

- We assess global perspectives on local political stability by measuring sentiment in global news. We measure how many times words related to politics are mentioned in articles that refer to a country. On top of this volume information, we retrieve the sentiment.

- The dataset derives from GDELT – Global Database of Event Language and Tone. It continuously monitors print, broadcast, and web news media in over 100 languages. We currently cover 63 countries to notably reflect the MSCI developed and emerging indices.

- Bilateral Stability Index: The aim of our bilateral relations index is to identify tensions and improving relations between two countries from a global viewpoint. We mirror the methodology used to measure local political stability but centre our analysis on pieces of news that relate to two countries.

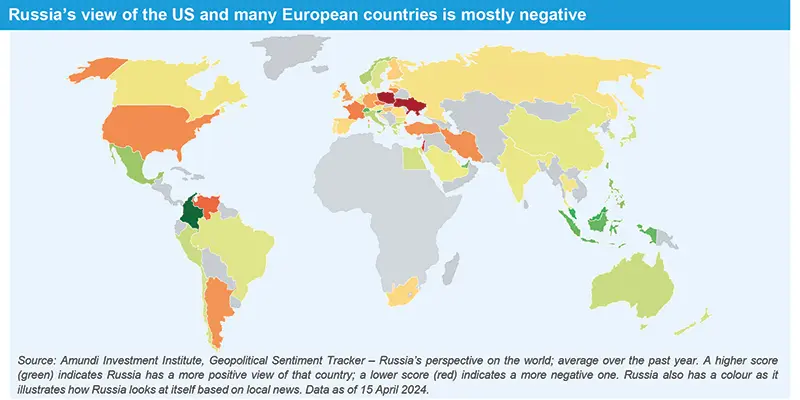

- Country viewpoint: The country viewpoint allows to observe the world through the lens of a specific country. To evaluate a country’s viewpoint on another country (or itself), we focus on articles published in its local sources that mention the country of interest.

- Political Stability Index & Country Scores: This is the ‘results’ index including all scores from the sub-indices above. It allows comparative analysis between countries based on fundamental stability, real-time local political stability and bilateral relations. The result is a comprehensive assessment of a countries’ comparative political risk.