Summary

This paper is the first of our ESG Thema series on social issues. The “S” pillar of ESG investing is increasingly on the agenda of investors, alongside environmental issues, as they have come to recognize the materiality of social risks. The first topic we will tackle as part of this series is that of respect for human rights, specifying how investors can integrate these fundamental rights in their investment and engagement strategies.

Key Take-aways

- Participating in the protection of human rights is a must, especially in a context of deepening inequalities around the world and a decline in respect for human rights.

- International organisations and NGOs work to promote human rights but companies and financial actors have also their role to play. Companies’ exposure to human rights violation is complex. It depends on their activity, their localisation and the localisation of the whole value chain (from supply chain to customer use).

- Human rights breaches represent a significant risk, be it related to the business, human resources or reputation of a brand. At Amundi, we aim at engaging companies on human rights to have them acknowledge the issue and to promote best practices

Introduction

According to the Human Freedom Index, “83% of the global population lives in jurisdictions that have seen a fall in human freedom since 2008. That includes decreases in overall freedom in the 10 most populous countries in the world.1 ” As shown by this quote, the respect for human rights has declined in recent years, demonstrating a rising need to ensure human rights are being respected and upheld globally.

Human rights must be fundamental for all. The principle of the universality of human rights is the cornerstone of international law. According to the United Nations, the first organisation who settled this definition, human rights are rights inherent to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status2. There is a wide range of human rights and many are interlinked:

As an asset manager, we recognize our connection to human rights and to potential human rights abuses through our activities, suppliers’ activities, and through our investment activities. Promoting human rights helps to address societal inequalities and supports a stable and robust society. One of our roles as an investor is to raise awareness and encourage the adoption of strong practices notably through active engagement with issuers. We see human rights violations as a breach to Amundi’s investment principles, and this is why we pay particular attention to company exposure to human rights risks. It is reflected in our responsible investment policy3 which considers the respect of the ten principles of the United Nations Global Compact (10 UNGC)4 deriving from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Labour Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, among others5. These principles are directed to companies with the idea of meeting their fundamental responsibilities to human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption.

Investors have a key role to play

As an investor and shareholder, advocating for these rights is a foundational element of our engagement strategy. The concept of social cohesion, which seeks to address disparities in wealth while strengthening the resiliency of society, is a strategic priority for Amundi. However, social cohesion cannot exist if human rights are not upheld.

At Amundi, ESG is fully embedded in our investments strategies and human rights play a key role within our ambitions around social cohesion. More specifically, Amundi aims to address human rights risks by encouraging companies to acknowledge their exposure to such risks and take concrete actions to prevent and address issues should they occur. On the quantitative side, our proprietary ESG rating tool assesses issuers using available human rights data. On the qualitative side, the ESG Research team monitors actual and potential human rights impacts at sector and company level and promotes Human Rights through engagement.

We believe that Human Rights Engagement is a two-pronged approach. The first aims to engage proactively on identification and management of human rights risks and the second reactively, when an abuse or allegation occurs to ensure companies are acting appropriately for effective remediation. This includes ensuring companies are taking into account UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights and OECD Due diligence guidelines. However, our aim is to ensure that company practices on human rights go beyond a reporting and compliance exercise to have a positive and tangible impact on their operations locations. Nonetheless, on this point, best practices are still emerging before being able to fully and effectively monitor them and react to human rights abuses accordingly.

Company exposure to human rights issues

Identifying, monitoring and preventing human rights violations is not only a government responsibility but also a corporate concern. Operations across a company’s value chain play a key role in human rights outcomes as reflected in the 10 principles of the UNGC. Companies are particularly exposed to the right to work in just and favourable conditions, the right to social protection, to an adequate standard of living and to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental well-being.

The non-respect of these rights represents a risk for companies in different ways and at different levels:

- At the Business level

- At the Supply Chain level

- At the User/Customer level

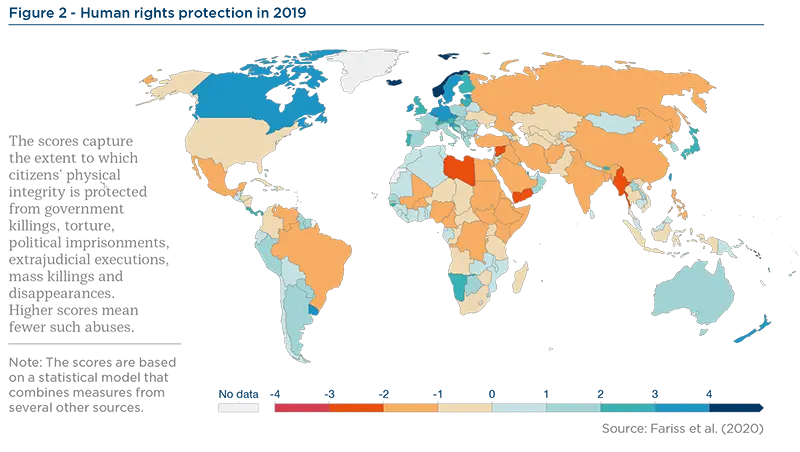

For companies, this means that they must put processes in place to address their exposure at all levels of operations, which is arguably not easy. In other words, this means addressing human rights risks across the entire value chain, from raw materials extraction to customers. This level of scrutiny must be strengthened even more depending on the location of its stakeholders. Especially, as shown in figure 2, the respect of human rights is not equivalent depending on countries and geography. To do so, companies should have a good understanding of their global exposure. One strong practice is mapping not only where in the value chain they are most exposed to human rights risks, but also where in the world this exposure is highest. This includes analysing their direct business locations, and the geographical locations of their supply chain (i.e. indirect operations - all tiers6 included), and when relevant, the potential impacts on customers and end-users in various regions of the world.

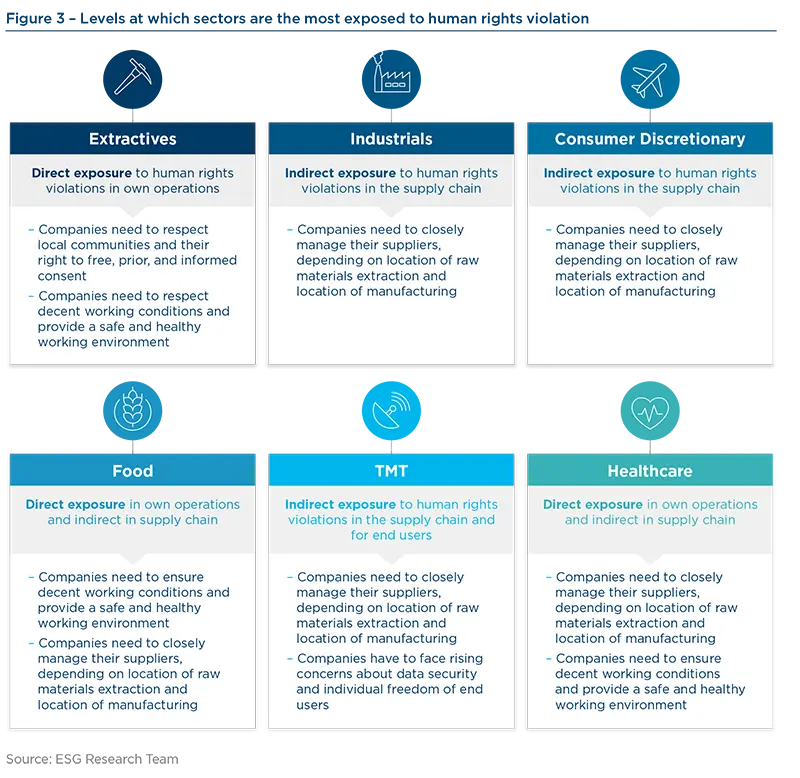

The nature of human rights risks in the value chain will vary by both sector and activity. Different sectors carry with them different sets of human rights risks. Though, ultimately, human rights risks must be mapped at the activity level because exposure to those risks can vary depending on the company (based on its own unique strategy and operations). Thus, it is every company’s individual responsibility to do this work.

For instance, when working with raw materials extraction and with manufacturers in some specific locations, the risk exposure is more tangible. As an example, agriculture has been identified by the International Labour Organization as being particularly prone to human rights abuses, such as forced labour, human trafficking and slavery. Therefore, in these cases, corporates have to apprehend human rights violations even more. The consequences they may face if any violation of these rights occurs can vary but are not negligible.

Companies will face higher exposure to the following non-exhaustive list of risks:

Reputational risk

There is a rising consumer awareness in regards to companies facing controversies and thus, controversies related to Human Rights are not exempt. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the reputation of a company accounts for 25% of its value7. The OECD adds that given the impacts of reputation damage, reputational risk management is a critical organisational function both to proactively protect against (prevent) and effectively deal with events (detect and respond) that may cause damage to a company’s reputation. It is all the more a concern for companies whose customers can easily chose alternative products if the brand does not align with their values.

Business risks

When companies misbehave and do not respect minimum required working conditions, there is an impact on the quality of the work done and thus on the financial well-being of the business.

Human resources risks

When companies do not respect minimum required working conditions, there is more chance of any accident to occur and employees are more likely to abandon their jobs. Eventually, the company can find itself in a dead-end.

Compliance/ Financial risks

Human Rights violation can expose companies to litigations and trials, which might lead to important fines

Case Study: Engaging on Human Rights in the Aerospace & Defence Sector

As an example, we decided in 2021 to engage on human rights with the aerospace & defence sector. As suppliers of components for aerospace and defence products, the industry is particularly exposed to human rights issues. Besides, companies face local regulatory restrictions. For instance, in the US, the government requires Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registrants who manufacture or contract to manufacture products containing conflict minerals to disclose the origin and status of minerals.

Contrary to common belief, the defence industry has not been the subject to the same level of scrutiny as other sectors, such as the extractive, agricultural, garment and technology industries, in relation to their human rights. Since the aerospace & defence industry is not dependent on consumer sales, companies tend to be less adversely impacted by public attention, compared to companies in other industries. This is why our approach is based on the supplier management angle. Besides, since aerospace & defence companies are suppliers dependent, we believe it is necessary for them to pay a particular attention to human rights management and issues, not only for their tier 1 but also for their tier 2, and tier 3 suppliers. Effective due diligence must be commensurate with risk, adequately resourced and geared towards the prevention of harm to others.

Key findings from our engagement:

- Human rights risks issues are not always considered less material. Some consider that they are not particularly exposed since they are European companies with strong labour rights in place.

- There are standards in place but they are minimal, and primarily linked to mandatory legal requirements. There are limited proactive actions beyond mandatory requirements such as dedicated trainings or human rights due diligence.

- Companies have processes in place to recognize and to denounce any human rights violations, such as a whistleblowing systems accessible to all stakeholders. However, there are no particular processes in place to prevent and address human rights issues that may occur across the value chain.

- Overall, processes are strong inside the business and at a tier 1 supplier level. We can expect more from aerospace & defence companies since it is a supplier-intensive sector that requires a strong knowledge of suppliers. A close relation with the suppliers and a good understanding of the origin of any component is essential to the proper functioning and the security of goods manufactured in this sector.

As seen with the aerospace & defence sector, addressing human rights due diligence with companies is complex. There is no one size-fits-all tool to prevent human rights violations. This is why companies need to start acknowledging the role they have to play to prevent and reduce any human rights violations.

Conclusion

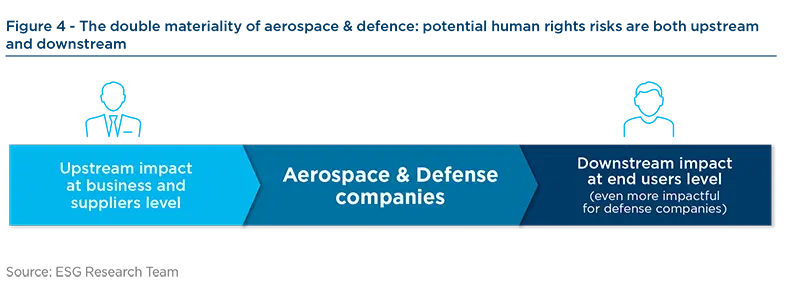

For companies, accountability is key. In other words, they need to view their operations through the perspective of double materiality (as presented in Figure 4) and go beyond regulatory minimum requirements. This means not only managing most material risks to the business but also human rights risks that are material to all stakeholders. Thus, if companies want to measure their social impact highlighted by the double materiality, they need to start considering human rights as a risk to people and not just to business.

As Eleanor Roosevelt said: “Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any map of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person: the neighbourhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.”

1. https://www.cato.org/human-freedom-index/2021

2. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/human-rights

3. https://about.amundi.com/ezjscore/call/ezjscamundibuzz::sfForwardFront::paramsList=service=ProxyGedApi&routeId=_dl_2f89a9f0-3100- 40f4-ad18-aed7160439cd

4. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/what-is-gc/mission/principles

5. Such as the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption

6. Supply chains consist of “Tiers” based on the closeness to the final product. The suppliers of modules and systems are directly underneath the original equipment manufacturer. These suppliers are supplied by component suppliers who in turn buy their goods from parts suppliers. See the following link for more details in the definition: https://ecosio.com/en/blog/what-is-a-tier-supplier/

7. https://www.novethic.fr/lexique/detail/risque-de-reputation.html