Summary

Key Takeaways

|

A large number of households and MSMEs lack access to finance

Financial inclusion3 spans savings, credit, payment services, insurance, and investments. Many low-income households and small businesses, particularly in developing countries, remain excluded or underbanked, relying mainly on cash transactions that expose them to risks and hinder their saving and investing activities. Credit access is often limited or costly, pushing many to informal lenders or expensive formal options. Digital finance—financial services delivered via mobile and internet platforms—is central to expanding access.

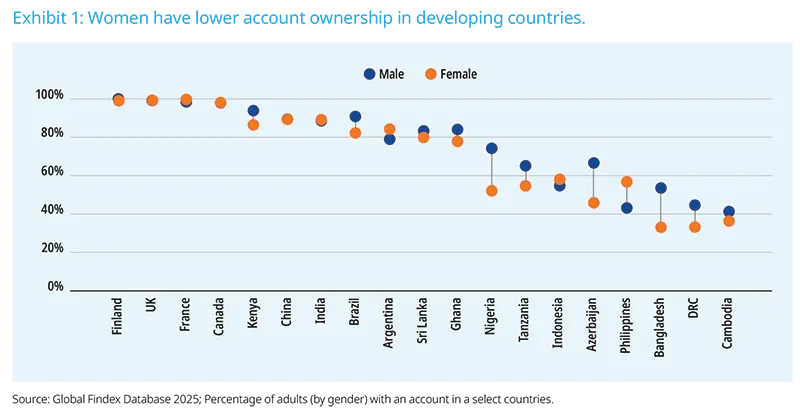

According to Global Findex Database 2025, about 1.3 billion adults worldwide did not have an account with a financial institution as of 2024. Low-income households face limited access to financial services, a result of both limited asset bases (to use as security, for example) and lack knowledge of available services. In some systems, minorities and immigrants face higher hurdles to access financial services. The elderly, especially due to branch closure combined with a tendency to avoid digital platforms also face higher risk of exclusion. Women are also a segment of society that banks need to target for inclusion. Globally, 81% of men have accounts compared to 77% of women, with the gap wider for low- and middle-income economies4 (see Exhibit 1).

Micro, Small and Medium Entreprises (MSMEs) is another segment that faces challenges accessing finance. MSMEs tend to have less stable income and cash flows, lack sufficient collateral, and often have less reliable financial data, and shorter credit history, generally leading to exclusion or underbanking. The global MSME financing gap—the difference between financing needs and credit extended—is estimated at $5.7 trillion, about 19% of cumulative countries GDP5. More than 130 million MSMEs, about 40% of MSMEs in developing/ emerging markets, remain excluded or underserved, per the MSMEs Finance Gap report.

Financial inclusion can support service provider’s profitability while reducing inequalities…

Broad, sustainable expansion of financial services into underserved segments (low income households, MSMEs etc) or new geographies (such as rural areas) can increase a provider’s market share. By addressing the unmet needs with scalable, low cost delivery models and appropriate risk controls, institutions can grow their customer base, diversify revenue sources, and build steadier, more profitable income streams over time.

Financial inclusion also diversifies a provider’s customer base, lowering concentration risk. By serving many individuals and MSMEs across different sectors and geographies, a bank can reduce credit concentration and broaden its deposit mix, which can ease funding pressure. That diversification makes the institution less vulnerable to stress in a single business line or region, thereby smoothing revenue and profit volatility and improving credit resilience.

Financial inclusion increasingly relies on digital platforms, removing one of the major hindrances to access to finance: limited branch network. The adoption of digital platforms tends to lower marginal cost per transaction, boosting efficiency indicators such as the cost-to-income ratio in the long-run. Goldman Sachs’ research6 on CEEMEA banks indicates a strong relationship between an increase in digitalisation in a country and the banks’ efficiency ratios. In the short term, it is essential for companies to invest in their IT systems. Research by McKinsey indicates that banks allocate about $650 billion annually to IT, with IT spending rising to 12% of revenue in 2022 from about 6% in 20137. We anticipate that banks will continue increasing their IT investments, particularly in applications and software. Additionally, fintech companies are expected to continue to challenge traditional banks within the digital finance space.

Expanding financial access is also beneficial to economic growth and poverty reduction. It supports Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including poverty elimination (SDG 1), food security (SDG 2), health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), and gender equality (SDG 5). Studies show financial inclusion reduces poverty8, income inequality and benefits governments by boosting business productivity, employment, and tax revenues.

…but there are also risks

Financial inclusion exposes companies to risks. Digital risks are at forefront. Greater reliance on digital platforms increases exposure to cyber threats and the likelihood of data breaches. These risks are amplified because many underserved customers lack awareness of digital risks and their rights, and some providers lack the resources or expertise to implement strong cybersecurity and data protection measures.

Another financial inclusion foremost risk is credit. Financial inclusion can increase credit risk because it extends services to individuals and businesses that are generally of weaker credit profiles due to their fragile balance sheets and more volatile profitability and cash flows. That raises the likelihood of missed payments and asset-quality deterioration for providers. Research9 by BIS indicates that, overall, delinquencies levels for Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) users in the United States are higher, at around 18.0% compared to about 7.0% for non BNPL users, underscoring the higher credit risks associated with some of the financial inclusion products.

Financial inclusion service providers are also vulnerable to money laundering and terrorism finance risks. This is mainly because some providers may not have ability to prevent, detect and investigate offenders. Financial inclusion products are generally of smaller values compared to traditional banking products, making them more cumbersome to monitor.

Financial inclusion can also create social risks that can develop into reputational, regulatory, legal, and financial risks. Rapid, digitally enabled access to credit can encourage over indebtedness and enable predatory lending practices. Widespread mobile money and digital credit adoption in Kenya10 contributed to elevated household debt burdens, while BNPL providers in the UK have faced criticism for facilitating unaffordable borrowing11. Easier financial access could also feed addictions such as gambling and impulsive spending.

Financial literacy can mitigate some of the risks

Financial education is a vital tool for mitigating many of the risks outlined above. Financial literacy plays a key role in supporting the financial well-being of a borrower. Research by Bruegel, a European economic think tank, demonstrates a positive relationship between financial literacy and the ability to manage debt levels effectively. The study highlights that individuals with higher financial literacy are better equipped to cope with unexpected income losses, showing greater resilience to financial shocks. Conversely, those with lower financial literacy tend to have fewer savings and are more likely to borrow under less favourable terms. Furthermore, countries with comparatively lower levels of financial literacy tend to have higher inequality markers12. As such, financial literacy is generally credit-positive for service providers, enhancing their clients’ financial stability and repayment capacity.

Financial literacy is especially critical in developing countries, where a significant proportion of the population struggles to use banking services without assistance. According to the Global Findex Database 2025, between 70% and 85% of adults in Pakistan, Malaysia, India, Vietnam, Tanzania, and Indonesia require help to effectively manage their accounts. Notably, women are five percentage points more likely than men to need support with using their mobile money accounts. This lack of experience leaves many account holders vulnerable to financial abuse.

Where are the opportunities?

Screening systems Long term banking assets growth in a system is a product of the level of penetration, indicated by the ratio of banking assets to GDP, wealth level indicated by the per capita income and the population. These are key long-term drivers of demand for financial services. Secondary drivers for financial inclusion include mobile penetration (critical for digital financial inclusion), a supportive regulatory environment, and an enabling funding ecosystem — including access to developmental finance and other forms of concessionary capital that supports providers focused on inclusion. Investors can prioritize countries with large or growing populations and high or rising per capita income, since these drive long term demand for financial services, and where current financial penetration is low, indicating unmet need. In general, wealthier nations have higher levels of financial services penetration and therefore limited opportunities.

|

Greater opportunities in Africa, LATAM and Asia; Focus on financial health and the elderly in developed economies

Emerging and developing countries provide better opportunities given their growing populations, expanding per capita income and low financial services penetration rates. Populous nations in Asia such as India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, and in Africa such as Nigeria, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo provide greater opportunities because a sizeable portion of their population remain underbanked or unbanked. In South America, Mexico and Colombia stand out due to the large population and low banking penetration.

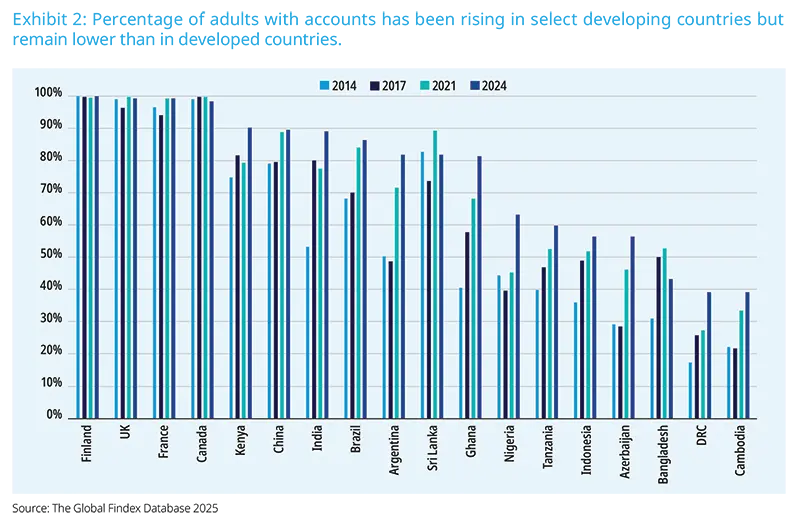

Account ownership in low- and middle-income countries is 75% compared to 95% in high income countries13. While account ownership in the developing countries is rising14 account penetration rates remain low (see Exhibit 2), making it more critical for banks in these systems to exploit opportunities.

By contrast, developed countries generally have high financial services penetration. This means banks must focus on customers’ financial health compared to access15. Financial health would require providers to create financial health charters or policies and guidelines on how to engage with their financially fragile consumer customers. Wealth management services are a significant opportunity in wealthier and developed countries. According to JP Morgan16, about half of Japan’s $17 trillion personal financial assets is owned by people aged 65 years or older, making this a key focus market.

Banks can take advantage of GSSS frameworks to structure products that can support financial inclusion, allowing investors to tap in

Financial institutions can issue bonds under Green, Social, Sustainable, and Sustainability-Linked (GSSS) frameworks to promote financial inclusion. One of the most accessible opportunities in this space is gender-based investing. Banks and lenders can structure bonds whose proceeds are dedicated to lending to women-owned and women-led businesses. For example, in Brazil, Itaú Unibanco raised about $396 million to support MSMEs owned by women17. Similarly, in Tanzania, NMB Bank issued its ‘Jasiri Bond’ with proceeds specifically aimed at financing women-led and women-owned enterprises18. In both instances, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) served as an anchor investor.

Banks can also develop borrowing products tailored to fund other underserved sectors. For instance, NatWest in the UK issued a €1.0 billion Affordable Housing Social Bond19, thus indirectly targeting the low-income households that benefit from affordable housing programs. Numerous segments of society, particularly in emerging markets, face limited access to finance. Trade financing for SMEs is a notable example where gaps remain significant. According to the WTO, globally about half of the trade finance requested by SMEs is rejected compared to about 7% for large multinationals, largely due to SMEs’ constrained balance sheets and weaker integration into global trade networks20. The limited depth and breadth of capital markets in developing economies often necessitate multilateral development banks to act as anchor investors. To incentivize investment, bonds can be structured with features such as coupon step-ups or increased redemption values if targets are not met. Additionally, insurance products can be employed to mitigate risks and enhance appeal, particularly in trade finance.

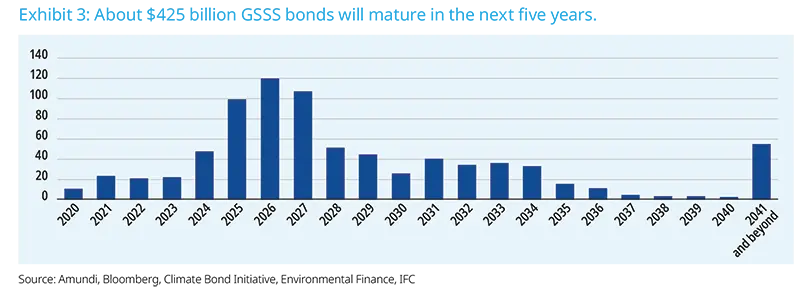

The GSSS bond issuance market is experiencing solid growth. In 2024, emerging market GSSS issuances reached 1.0 trillion21, a record high. While it is challenging to identify bonds exclusively targeted at promoting financial inclusion, gender-based bonds have emerged as a prominent example, as highlighted earlier. Both investors and issuers have a significant opportunity to expand the range of products, especially given the large volume of GSSS bonds set to mature in the coming years. In emerging markets, about $425.0 billion worth of GSSS bonds are maturing between 2025 and 2030, compared to just $127.1 billion over the past five years (see Exhibit 3). Several factors, including the current higher levels of interest rates, may influence the attractiveness of rolling over these bonds but issuers can capitalize on this opportunity by structuring bonds that appeal to investors.

Financial inclusion is a major ESG social pillar for Amundi

During its engagement process, Amundi encourages companies to expand access to finance to various groups, and to create financial inclusion policies and financial health charters. Amundi has conducted several engagement initiatives on financial inclusion, covering over 50 companies so far this year. Below we present two best practice examples, with one on financial inclusion while the other is on financial health.

Case studies A Brazilian bank that expanded financial access via its digital channels Nu Holdings is a branchless digital bank serving consumers and SMEs in Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia. As of December 2024, it reached roughly 114 million customers (up from ~20 million in 2019) and grew annual revenue to $11.5 billion from $612 million over the same period — illustrating the scale and commercial potential of digital financial inclusion. Nu delivers banking services through an app-based platform, offering credit cards, personal loans, deposit accounts, investment products via NuInvest, micro insurance and SME lending. A number of its products have no maintenance fees and require minimal credit history: for example, digital accounts offer free unlimited transfers, while micro loans can start with limits as low as $10 and expand as customers build a track record. These features allow Nu to reach previously underbanked and unbanked segments. To facilitate cash access, Nu partners with retail networks. Notably, a recent agreement with Oxxo (over 22,000 stores in Mexico) allows in-store cash withdrawals for Nu customers, with deposits planned for the future. Nu also partners with other retail supermarkets.

A French regional bank has a public financial heath charter Credit Mutuel Alliance Fédérale is a cooperative alliance of 14 federations with around 4,500 branches across France. Its extensive branch network supports financial inclusion, and the group has formalised its commitment to customer financial health through a public “vulnerable customers” charter — a best-practice framework we recommend other banks adopt. By proactively managing financially fragile customers, the bank reduces regulatory, reputational and credit risk. The charter operates alongside regulatory requirements for basic banking access. To assist customers, Credit Mutuel offers online budgeting and transaction management tools, an optional Credit Mutuel also provides debt management counselling and tailored repayment plans, supported by a regional team of about 50 staff dedicated to helping customers manage debt. The bank partners with organisations such as ADIE, Initiative France, and France Active to expand micro credit and targeted support for jobseekers, people with disabilities and social benefit recipients. |

The Credit Agricole group has a global partnership with micro finance institutions: Through the Grameen Credit Agricole Foundation, Credit Agricole supports 67 micro-finance institutions (a majority of them being medium-sized) in Sub Sahara Africa, South and South East Asia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Middle East, Europe and North America. In 2024, the foundation disbursed €38.33 million, with €34.9 million of it being new loans. The GCAF also provided technical assistance to 25 partners.

Conclusion

Financial inclusion creates financial and social benefits to providers

Despite improvement in access to finance for most adults over the past decades, there are still many adults and MSMEs that are underbanked or unbanked. Low-income household and women are especially vulnerable groups in the developing countries while the elderly face exclusion risk in the developed countries.

Financial inclusion brings financial benefits to service providers. A service provider can diversify its assets and liabilities, limiting concentration risks, and can employ digital technology to improve its efficiency and profitability. From a social perspective, financial inclusion can reduce inequality, especially income and gender inequalities which are some of the most pressing forms of inequality. That said, financial services providers would need to ensure that cyber-related and credit risks are appropriately managed.

Investors should request financial services providers to create robust public financial inclusion policies and financial health charters for the financially fragile, and low-income households. Amundi leverages its engagement capabilities to encourage financial services providers to expand financial access and financial literacy. Amundi will continue to advocate for financial services providers to broaden their efforts in the financial inclusion space.

1. These are individuals aged 15 years and above

2. Global Findex defines account ownership as having an account at a bank or similar institution such as a credit union, micro finance, post office or with a mobile money provider

3. The World Bank posits that financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs, delivered responsibly and sustainably. The Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion describes it as a state where all working-age adults have effective access to credit, savings, payment, and insurance from formal providers. Financial health complements this by assessing how inclusion impacts financial security, freedom, and resilience.

4. Global Findex Database, 2025

5. MSME Finance Gap

6. Goldman Sachs: Digging into digital

7. McKinsey & Company: Managing bank IT spending: Five questions for tech leaders

8. Suri and Jack (2016): The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money

9. BIS: Buy now, pay later: a cross-country analysis

10. Business Daily: Alarm as easy digital loans yoke more Kenyans into debt

11. The Guardian: Fears of spiralling debt as BNPL credit quadruples in UK

12. Bruegel: The state of financial health in the European Union

13. The Global Findex Database 2025.

14. As examples, account ownership has increased by 41 percentage points in Ghana, to 81% in 2024 from 41% in 2014. Similarly, in India, account ownership leaped to 89% in 2024 from 53% in 2014.

15. There are other segments that still need easier access to finance e.g. the elderly, MSMEs, migrants etc.

16. The Sustainable Investor: Alpha generation in financial inclusion

17. Itaú Unibanco: Itaú Unibanco raises R$ 2 billion in financial bonds to support women’s entrepreneurship

18. NMB: NMB Bank Plc opens another bond investment opportunity for socio-economic empowerment

19. NatWest Group announces updated £7.5bn UK social housing sector lending ambition

20. WTO: Small businesses and trade

21. IFC: Emerging market green bonds market 2024