Summary

-

Biodiversity losses may have a material effect on some companies, but companies also erode biodiversity through their activities and practices.

-

A bespoke ESG rating process and investment framework can ensure that biodiversity issues are taken into account in portfolio construction.

-

We believe that a biodiversity-oriented approach should exclude the weakest issuers regarding practices and policies, while favouring those with over 20% of revenues linked to natural capital themes, or over 80% aligned with providing climate change solutions.

-

In our view, the most appropriate measure to assess and compare the biodiversity footprints of companies and sectors is the Mean Species Abundance (MSA) metric1.

-

Engagement with companies on biodiversity issues in their operations and value chains is crucial.

Summary of key messaging

Integrating biodiversity risks into investment frameworks is becoming more and more relevant. Biodiversity refers to the diversity of living organisms and is assessed at three different levels - the diversity of ecosystems (i.e. terrestrial, marine and aquatic), species and genes. It is integral to the health of soils, plants and animals, but also to the supply of clean water, waste decomposition and agricultural productivity as well as human health and mental well-being. However, biodiversity is being destroyed at a rapid rate. According to the Convention on Biological Diversity global investment in biodiversity conservation requires approximately USD536 billion annually by 2050. Yet, current annual expenditure falls heavily short of that, amounting to USD133 billion2. This has implications for businesses globally, with the size of this threat only now coming into full view. Many companies have an impact on nature, but also are dependent on it. For example, 3 of the 18 sectors within the FTSE 100 Index are linked with production processes that rely on it3. Meanwhile, companies contribute to biodiversity loss through their activities, or the location of their operations and supply chains. A rising awareness of this interrelationship between companies and biodiversity has ensured that related issues are increasingly factored into equity and fixed income portfolio construction.

To enable this, we believe investors should embrace a bespoke ESG rating process and biodiversity investment framework. This can involve excluding the weakest companies in terms of practices or policies, while favouring those with over 20% of revenues linked to natural capital themes, or over 80% aligned with providing climate change solutions. Using a biodiversity indicator – the Mean Species Abundance (MSA) metric – the biodiversity footprints of portfolios, companies and sectors are measured and compared. This data enhances investors’ ability to have a high level of engagement with companies on biodiversity issues in companies’ direct operations and value chains.

The Vital Role of Biodiversity

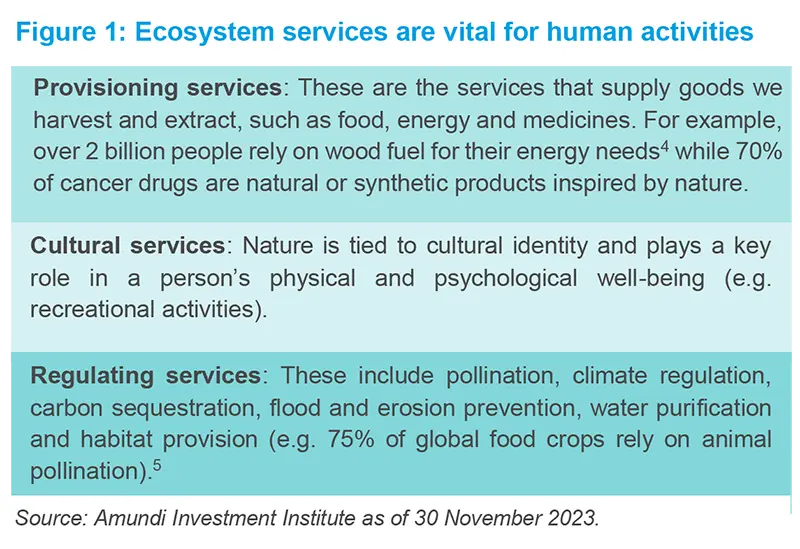

Biodiversity is part of the Earth’s natural capital and considered the cornerstone of a well-functioning planet. It refers to the diversity of living organisms and is assessed at three different levels - the diversity of ecosystems (i.e. terrestrial, marine and aquatic), species and genes. Biodiversity contributes to the health and resilience of soils, plants and animals, and benefits humans, being integral to the provision of clean drinking water, waste decomposition and agricultural productivity as well as human health and mental well-being. Collectively, these benefits are known as ecosystem services, and include a variety of types (see Figure 1 below).

Economic growth has resulted in a rapid decline in biodiversity. According to the World Wide Fund (WWF) Living Planet Report, almost 60% of wild animal populations have disappeared in the space of 40 years6. Biodiversity loss can lead to a rise in food prices and diet-related diseases as well as threaten local livelihoods and economies. In fact, over the last five years, the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Reports have gone as far as identifying this loss as being a mid- to high-level global risk in terms of impact and likelihood.

Turning to companies, many are reliant on nature, reflected in the estimate that over 50% of global GDP is moderately or highly dependent on it7. Hence, biodiversity loss has implications for businesses globally, and the size of this threat is only now coming into full view. For example, 3 of the 18 sectors that comprise the FTSE 100 Index are linked with production processes that require nature. Conversely, companies’ actions can be notable contributors to biodiversity loss through the nature of their activities (e.g. deforestation) or the location of their operations (or supply chains) in biodiversity sensitive areas.

The financial estimates of the effect of biodiversity loss have now reached staggering levels (see appendix 1). For example, according to the Convention on Biological Diversity, global investment in conservation requires approximately USD536 billion annually by 2050, but current annual expenditure falls heavily short of that, amounting to USD133 billion. While these estimates come with limitations, it is clear that biodiversity-related risks are pervasive. This has led market participants – including central banks through the momentum created by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS)8 – to assess biodiversity risks and determine the process of integrating them into investment processes.

Measuring Biodiversity and building an investment framework

To assess companies’ exposure to biodiversity risks and opportunities as well as their conduct concerning biodiversity, we believe investors should rely on a rating process that involves:

- Drawing on environmental information from data providers and internal research tools

- Monitoring controversies using various sources to identify environmental damage that is affecting biodiversity

- Applying caps to the relevant criteria of the ESG scoring of issuers that have insufficient risk management of activities with a high negative influence on biodiversity

- A lack of appropriate processes or disclosures can also be a reason to cap biodiversity-related criteria of the ESG scoring.

There are still notable challenges in accounting for biodiversity, such as limitations around data measurement and a lack of clear reporting standards. Yet, this complexity is not an excuse for inaction.

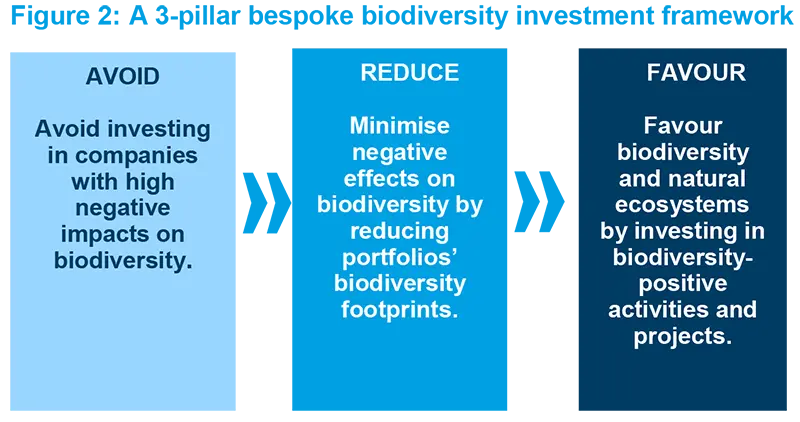

Building on this ESG rating process, investors should embrace a wider investment framework in order to assess and integrate biodiversity issues into their investment strategy. In our view, this framework must be based on 3 pillars (see Figure 2 below). The aim of such an approach is, on the one hand, to minimize biodiversity-related risks in investment portfolios, and on the other hand, to invest in companies that are leaders on biodiversity-related matters.

1. AVOID

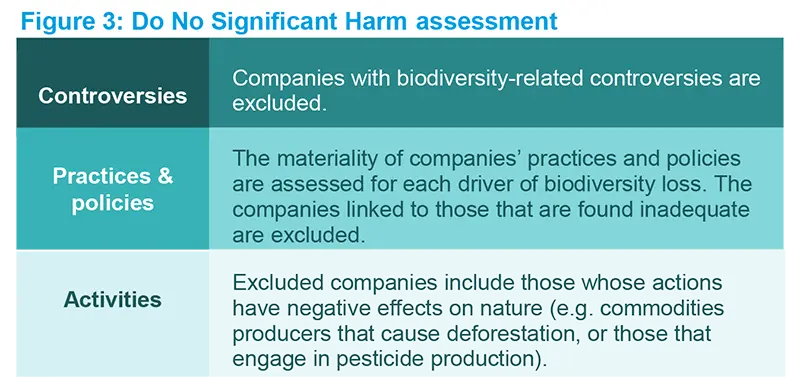

We undertake a “Do No Significant Harm (DNSH”) assessment9 based on 4 of the 5 drivers of biodiversity loss identified by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (2019): the changing use of land and sea; direct exploitation of organisms; climate change; pollution; and invasive non-native species10. This DNSH is conducted across several dimensions (see Figure 3 below).

On top of this, we carry out an assessment of companies’ activities which negatively affect biodiversity sensitive regions, on the basis of the definition of Principal Adverse Impact (PAI) 711. Specifically, this will serve to identify and exclude companies with operations which are damaging these areas and also exclude the worst-performers on our “Biodiversity and Pollution” environmental sub-criterion12.

2. REDUCE

This second pillar aims to track portfolios’ biodiversity footprints. The MSA13 metric is used, which expresses the mean abundance of original species in a habitat compared to what it would be in an undisturbed habitat. It ranges from 0% to 100%, where 100% relates to a species group that is intact, and 0% to all original species that are locally extinct. It can track changes in ecosystems over time.

To calculate biodiversity footprints over a surface, we use the MSA part per billion (ppb) metric. It accounts for the difference in time between static impacts (accumulated negative effects on biodiversity) and dynamic impacts (periodic gains and losses of biodiversity). The static footprint includes all the long-lasting effects which remain over time, while the dynamic footprint is caused by changes during the specific period assessed. When comparing footprints across companies and sectors, we use the MSA part per billion of revenue metric. This quantifies the effect of companies’ activities and value chains on their environments. The objective of this measure is to link companies’ economic activities and the pressures exerted on biodiversity. Thus, it is useful in managing investments, such as enhancing investors’ abilities to engage with companies on biodiversity concerns. Moreover, monitoring the portfolio’s MSA can also allow investors to report more easily on their investments’ biodiversity footprints, which will increasingly be required by regulators in the years to come.

Additionally, we believe portfolios should be invested to a notable extent in sectors facing biodiversity-related challenges. Investing in these “high biodiversity impact sectors”, while excluding the worst performers in their respective sectors, is a way to seek change in the real economy and encourage companies to continuously improve their practices and policies through engagement.

A starting point in integrating biodiversity into portfolios is to tilt them away from issuers that have high biodiversity footprints and no ambition to reduce them, towards those that are lowering biodiversity risks.

3. FAVOUR

The third pillar aims to invest in issuers that are leaders on biodiversity-related matters. To measure environmental impact, we rely on both climate change and natural capital indicators (see Figure 4). Eligible companies are identified by screening for those that have more than 20% of their revenues linked to natural capital themes, or more than 80% aligned to climate change solutions. We selected these thresholds in order to maintain a high level of ambition on natural capital and climate change indicators, while not being too restrictive on the investment universe.

As seen in Figure 4, climate-related indicators are also included in the framework, as climate change is intertwined with the objective of preserving biodiversity. Indeed, it is one of the key drivers of biodiversity loss, with changes in the marine, terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems resulting in a loss of species, a greater probability of diseases and, eventually, a mass mortality of plants and animals. At the same time, biodiversity is also essential to limit climate change. Terrestrial and marine ecosystems act as carbon sinks, absorbing around half of the greenhouse gases emitted14.

Selecting corporate leaders focused on climate change solutions can be a way to identify those that are indirectly favouring biodiversity preservation.

On the credit side, green bonds that are financing biodiversity positive projects are favoured. The categories of eligible projects under the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) Green Bond Principles15 include: pollution prevention and control; environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land use; terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity conservation; and sustainable water and wastewater management.

Engagement encourages corporate change

Although corporates both affect and depend on biodiversity, they are still early in the process of determining how to measure, address and report on biodiversity-related metrics. To accelerate action, investors should also engage16 to help companies address biodiversity risks. The objectives are two-fold:

- Increase awareness of biodiversity loss to accelerate corporate action

- Identify current industry best practices and disseminate these recommendations to corporates

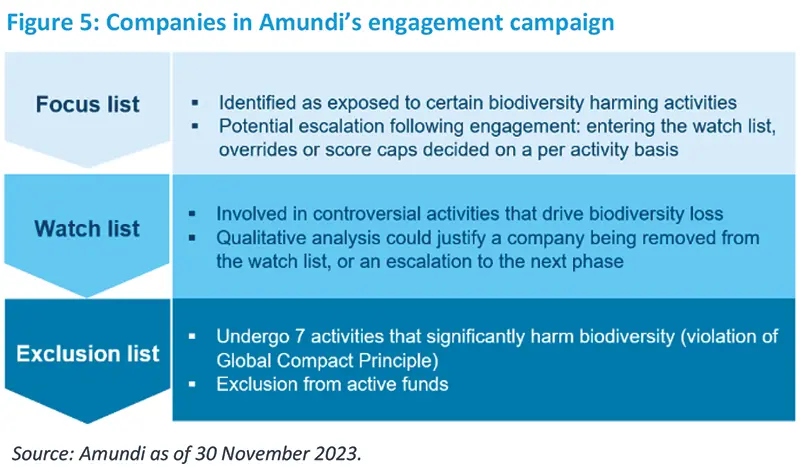

Investors should derive a focus list of companies (see example in Figure 5) and others for which biodiversity is deemed relevant. The engagement focuses on the management of biodiversity issues and ecosystems risks, not only in direct operations, but also in value chains. When an abuse or allegation occurs, investors should communicate directly, or in collaboration with other investors, in seeking assurance that measures will be taken for effective remediation. When engagement fails, or if the action / remediation plan of an issuer appears weak, the company should be excluded from the investment universes and escalation strategies begin, such as: negative overrides of ESG criteria; questions at Annual General Meetings (AGMs); votes against management; public statements; ESG score caps; and, ultimately, exclusions if the matter is critical.

Amundi’s 2022 engagement campaign on biodiversity

In 2022, 119 companies were engaged on their biodiversity strategy. As part of this commitment, Amundi provides recommendations to improve the integration of this theme within their strategies. Amundi has also strengthened its shareholder dialogue on the preservation of natural resources. More broadly, 344 companies were engaged through various programmes, including the promotion of a circular economy and better management of plastic, the prevention of deforestation, and various topics including pollution control or sustainable management of water resources.

Bringing the investment approach to life in fixed income

As one of the leading banks in Italy with significant ESG commitment, this company has issued more than 8.5 billion euros of green bonds which are focused on renewable energy, the circular economy, green buildings and biodiversity. In the company’s sustainability framework, green eligible projects within the category - Environmentally sustainable management of living natural resources and land-use - include those aimed at developing sustainable agricultural practices as well as conserving nature and biodiversity. Some good examples of such projects are those in carbon farming17 and forestry (e.g. loans to afforestation, reforestation and forest management). In addition, projects that generate negative environmental impacts are excluded.

Turning to the circular economy, we identified this as having a notable positive impact on biodiversity as it reduces the demand for primary resources18. The bank has a strong commitment regarding this economy, with an 8 billion euro financing upper limit within its new 2022-2025 Business Plan. Even prior to this plan, the banks’ green bonds had a significant allocation to this area, financing projects aimed at: increasing the efficiency of resource use within a company, or along its supply chain; production processes using products made of renewable or recycled resources; and loans related to the replacement of non-recyclable materials with recyclable materials.

A leading provider of renewable products based on wood and biomass has a strong focus on sustainability and innovation. With low-carbon, renewable and recyclable fiber-based products, the company aims to be a leading player in driving the transformation towards a bio-based circular economy.

To achieve this aim, the company has committed to reaching a net-positive impact on biodiversity in its own forests and plantations by 2050 through active management. Furthermore, it has issued 7 green bonds which are financing projects that fall within one of the eligible categories: sustainable forest management; renewable, low-carbon and eco-efficient products, product technologies and processes; energy efficiency; renewable energy and waste to energy; sustainable water management; and waste management and pollution control.

In their most recent impact report, the company disclosed information on projects funded, such as:

- Restoration of native forests and conservation of biodiversity: In Sweden, the company achieved a positive climate impact through the carbon sequestration taking place in its forests. As an average of 2020–2022, these sequestered an estimated 1.7 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per annum.

- Sustainable product processes: These projects related to the R&D, equipment, processes and technologies used in the manufacturing of bioeconomy products. These will increase substitution from fossil alternatives and non-renewable materials. An example of increased recycling is the replacement of plastic in take-out food packaging through using the company’s plastic-free, recyclable formed fiber products.

OTHER RESEARCH BY AMUNDI ON BIODIVERSITY

- Biodiversity: It’s Time to Protect Our Only Home - N°1 It's time to sound the alarm on biodiversity

- Biodiversity: It’s Time to Protect Our Only Home - N°2 Addressing Biodiversity Loss

- Biodiversity : It’s Time to Protect Our Only Home - N°3 Addressing Biodiversity in Mining & Metals, Utilities, Paper & Forest Products

- Biodiversity: It’s Time to Protect Our Only Home - N°4 Addressing Biodiversity in Food-based Sectors

- Biodiversity: It’s Time to Protect Our Only Home - N°5 Managing Biodiversity in the Insurance Sector

- Biodiversity: It’s Time to Protect Our Only Home - N°6 Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals sectors

- The Market Effect of Acute Biodiversity Risk: the Case of Corporate Bonds

Research has highlighted a range of estimates concerning biodiversity loss. For example: the World Bank has attempted to link biodiversity loss to its associated economic impact, with results in some countries indicating a 20% GDP loss; other research claims that the financing gap to restore biodiversity up till 2030 will reach USD711 billion annually, but as of 2019, only USD143 billion per annum (16%) had been invested19; and the Convention on Biological Diversity forecasted that the global investment in biodiversity conservation requires approximately USD536 billion annually by 2050, but the current annual global expenditure falls heavily short of that, amounting to USD133 billion.

In December 2022, the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP 15) introduced clear targets for biodiversity conservation in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)20. These targets included the aim to conserve 30% of land and oceans by 2030. To support this target, countries agreed to gather a minimum of USD200 billion per year from both public and private funds, and to raise USD30 billion per year from developed nations to benefit developing countries. However, there is a need to better understand how companies impact and depend on biodiversity for these commitments to become concrete.

Companies must provide dedicated information in order for investors to better consider biodiversity-related risks and opportunities in their investment decisions. With enhanced information, capital allocation will be driven away from activities harming biodiversity to those limiting negative impacts, or even providing solutions to preserve and restore biodiversity. It will also contribute to the assessment of physical and transition risks in investment portfolios. Key biodiversity linked elements (e.g. climate, water, pollution and resource use) need to be properly accounted for as a foundational element of corporates’ environmental strategies. This is hoped to be achieved by the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)21, which requires more comprehensive company reporting on sustainability impacts.

For investors, being able to assess their portfolios’ biodiversity impacts and dependencies is particularly important in light of the disclosure requirements at the European level. The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)22 implemented a series of mandatory ESG disclosures for financial market participants and advisers, including reporting on the Principal Adverse Impacts (PAIs) of their portfolios. Specifically, the PAI Indicator 7 requires that activities are disclosed that negatively affect biodiversity sensitive areas. Furthermore, in France, Article 29 of the Law on Energy and Climate (LEC) has extended requirements for annual reporting by financial investors to include information on long-term alignment with biodiversity goals. Investors should also be able to quantitatively measure and report on the impacts of their investments on biodiversity, as well as their exposure to biodiversity-related risks.

As of today, there are significant hurdles to effectively account for biodiversity, such as challenges around data measurement and a lack of clear standards for reporting. However, this complexity should not be an excuse for inaction. Work on the topic is moving fast: guidance is provided by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)23. This gives companies a concrete framework to help them comply with new transparency requirements

We signed the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge in 2021, which consists of 5 steps financial institutions promise to take: collaborating and sharing knowledge; engaging with companies; assessing impact; setting targets; and reporting publicly on the above before 2025.

In the context of signing this pledge, we are involved in a number of working groups:

- Impact assessment (including biodiversity measurement and data): members share case studies, best practices and lessons learned on the different approaches to biodiversity measurement.

- Engagement with companies: members disclose experiences on biodiversity related engagement, with companies aiming to build upon (not duplicate) the work of other collaborative initiatives.

- Public policy & advocacy: members communicate with governments on public policy to reverse nature loss.

- Target setting: members share experiences, new developments and explore science-driven global goals, targets and frameworks.

Assessing companies on biodiversity: To deliver on our commitments, we developed (2023) a dedicated Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services Policy, which will be fully integrated into our Responsible Investment Policy. This policy is applicable to issuers with activities which have the potential to critically impact on forests/deforestation and water through deep sea mining and extractives activities (e.g. metals & mining, oil & gas companies) in biodiversity sensitive areas. In addition, this policy is also relevant to companies exposed to pesticide production and single use plastic producers and users. It covers the way in which we rate issuers exposed to biodiversity risks and communicate with those on the internal focus list to help them integrate biodiversity and ecosystem services in their strategies. Furthermore, the policy outlines how we implement an escalation process when engagement fails, or when an issuer’s remediation plan is deemed weak.

Collaborative engagement: As well as undertaking corporate campaigns related to biodiversity, we participate in collective initiatives. We signed the Nature Action 100 initiative, whose aim is to drive greater corporate action to reverse nature and biodiversity loss, and take part in the FAIRR initiative, a collaborative investor network that provides tools to manage investment risks and opportunities in the food sector. Our ESG analysts participate in several working groups related to biodiversity: waste and pollution, sustainable aquaculture and anti-microbial resistance.

Public policy & advocacy: Beyond corporate engagement, we work with the wider ecosystem of stakeholders to address biodiversity loss. This includes engaging with policymakers, both directly and collaboratively with other investors, to emphasise the need for ambitious national and international policies around biodiversity issues.

- In 2021, we spoke on behalf of the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge and the financial sector during the High Level Segment of the Conference of the Parties. We outlined the financial community's desire to participate in the fight against biodiversity loss, as well as encourage the setting of ambitious targets for the Global Biodiversity Framework. These targets need to be supported by an appropriate regulatory framework.

- We also contributed to the COP15 in 2022 as a member of the Finance for Biodiversity Foundation’s delegation along with 25 other financial institutions. The Finance for Biodiversity pledge notably advocated for the final version of the Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) to include explicit language that supported the alignment of financial flows with the global biodiversity goals outlined in the framework.

- Finally in 2022, we participated in the One Ocean Summit, held within the context of the French Presidency of the Council of the EU and with the support of the United Nations. We announced the beginning of a close collaboration with the Fondation de la Mer, which has developed a framework to help companies to measure impacts and make positive changes in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #14 “Life below water”. This goal seeks to conserve the oceans and seas, and use marine resources sustainably.

Sources and References

1. Source: Marques A., Robuchon M., Hellweg S., Newbold T. & Behe J. (2021), “A research perspective: towards a more complete biodiversity footprint: a report from the World Biodiversity Forum”, International Journal of Life Cycle Analysis 26: 238- 243.

2. Source: The United Nations Environment Programme 2021, State of Finance for Nature.

3. Source : United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI).

4. Source: The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2019). This is an organisation established to improve the interface between science and policy on issues of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

5. Source: Institute for the Biotechnology of Infectious Diseases.

6. Costanza R., De Groot R., Sutton P., Anderson S., Kubiszewski I., Farber S., Turner K. R. and Van Der Ploeg S. (2014), “Changes in the global value of ecosystem Services”, Global Environmental Change, Volume 26, May 2014, Pages 152-158.

7. Source: World Economic Forum, Davos (2020).

8. Launched in 2017, the NGFS is a network of central banks and financial supervisors that aims to accelerate the scaling up of green finance and develop recommendations for central banks’ role in climate change.

9. The DNSH (do no significant harm) principle is integrated into the EU taxonomy regulation. This principle requires companies not to cause any harm to the 6 environmental objectives which determine the sustainability of an activity: mitigation of climate change; adaptation to climate change; sustainable use of marine resources; the circular economy; pollution prevention/reduction; and protection/restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

10. The invasive non-native species driver of biodiversity loss is not included in our assessment due to the current lack of data available on the topic.

11. A Principle Adverse Impact (PAI) is any impact of investment decisions or advice that results in a negative effect on sustainability factors, such as environmental, social and employee concerns, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and anti-bribery issues.

12. The Biodiversity and pollution rating criterion is integrated into the Environment pillar of our proprietary rating.

13. There is no consensus over which methods and indicators are best in assessing biodiversity. However, researchers and companies are increasingly using the MSA metric as their key measure.

14. Source: United Nations Environment Programme (November 2021), Five ecosystems where nature-based solutions can deliver huge benefits.

15. The Green Bond Principles (GBP) seek to support issuers in financing environmentally sound and sustainable projects that foster a net-zero emissions economy and protect the environment.

16. Amundi launched an engagement campaign dedicated to biodiversity strategies in 2021.

17. Carbon farming refers to agricultural methods that improve the uptake and storage of carbon dioxide in soil.

18. Source: European Environment Agency, The benefits to biodiversity of a strong circular economy, June 2023.

19. Deutz A., Heal G. M., Niu R., Swanson E., Townshend T., Zhu, L., Delmar A., Meghji A., Sethi S. A., and Tobin de la Puente, J. (2020), “Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap”, The Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

20. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. It was adopted in December 2022 at the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

21. A new EU Directive that replaces the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and seeks to ensure alignment with the EU sustainable finance agenda, particularly in relation to the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities.

22. EU legislation that imposes assessment and disclosure requirements for labelled product providers and advisers in the EU. The technical guidance on core and supplementary reporting metrics came into force in March 2021. All sustainable funds (i.e. financial products that have sustainable investment as their objective (Article 9), or which promote environmental and/or social characteristics (Article 8)), are required to disclose the percentage of assets invested in activities eligible under the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities.

23. The TNFD was launched in June 2021 to provide a reporting framework for companies and financial institutions to disclose their nature-related risks, such as biodiversity loss or the degradation of ecosystem services.