The new governance proposed by the Commission goes in the right direction, but risks of failing are high.

After several months of informal negotiations, the European Commission proposed on 9 November a reform of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) to be debated. Only the broad outlines of the reform have been presented. The Commission has deliberately left the most politically sensitive details open. The reform of the fiscal rules must thus be adopted next year.

While investors’ eyes remain riveted on the timing and extent of the ECB’s monetary policy normalisation (key rates and balance sheet), it is on the fiscal policy side that tensions are most acute among Europeans.

The ‘general escape clause’ made it possible to suspend the fiscal rules of the SGP during the Covid-19 crisis. With the war in Ukraine, this safeguard clause was extended until 2024, allowing European states to implement stabilisation measures without any institutional constraints.

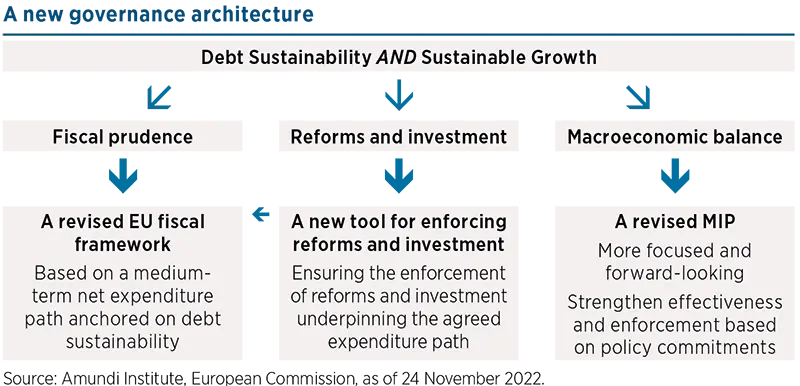

At the same time, a consensus emerged that the rules of the SGP needed to be reviewed. Many proposals were on the table. After several months of informal negotiations, the European Commission proposed on 9 November a reform of the SGP to be debated. The Commission calls for “a simpler and integrated architecture for macro-fiscal surveillance to ensure debt sustainability and promote sustainable and inclusive growth”.

Only the broad outlines of the reform have been presented. The two fundamental pillars of the pact have been maintained (a public deficit limited to 3% of GDP and a debt-to-GDP ratio below 60%). However, these numerical targets are no longer binding: the focus has shifted to the medium-term adjustment and the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach is de facto abandoned. The aim is to avoid pro-cyclical fiscal policies, which is good news.

In practice, it would be up to each country to define its own debt and deficit reduction path, instead of the current uniform rules. The idea is to empower member-states. The Commission would present each member-state with a debt adjustment path over a period of four years, with an additional three years warranted to countries whose public debt exceeds 60% of GDP, provided that they commit to structural reforms and strategic growth-enhancing investments.

The new framework should address current challenges and help make Europe more resilient by reducing public debt ratios in a realistic way without sacrificing strategic investment spending. The Commission proposes to play a greater role in assessing national budgetary plans. Two difficulties arise here: firstly, this process presupposes calm negotiations between each state and the Commission. What will happen in the event of disagreement? The second difficulty, linked to the first, lies in the typology that will be adopted. Which criteria will be used to dif ferentiate among countries? The Commission has deliberately left the most politically sensitive details open. The problem posed is anything but new: how can northern countries be reassured about debt sustainability if indebted countries are given too much leeway to avoid pro-cyclical policies or the sacrifice of necessary spending.

Divisions remain deep in the Eurozone concerning this reform. The four-to-seven-year adjustment period for countries that ‘break’ the rules to put their debt on a permanent downward trajectory is considered too lax by the Germans. Germany has proposed that an independent budgetary watchdog should replace the Commission to analyse debt sustainability independently and make recommendations. This proposal has little chance of being accepted by other member-states.

The Commission has deliberately left the most politically sensitive details open.

Meanwhile, the ECB is concerned about the lack of coordination of fiscal policies. Governments must continue to support the fight against inflation, but they should not stimulate demand. This is the ‘3Ts rule’ presented by Christine Lagarde: budgetary measures must be Temporary, Targeted, and Tailored. The fact is that they are insufficiently targeted. Moreover, countries need to align their fiscal policies and energy support measures better with the monetary policy stance. Otherwise, the ECB may have to raise its key interest rates further (i.e., more than currently expected) to anchor inflation expectations.

At present, divisions prevail and a deadlock cannot be completely ruled out. Long months of negotiations lie ahead. The Commission is due to receive comments from member states by the beginning of 2023. It is unlikely that the Europeans will reach an agreement quickly. However, they need to agree as soon as possible on the main principles and best practices for fiscal support, because, at the end of the day, the current approach may not only lead to undesirable results on inflation, but may also prove incompatible with medium-term debt sustainability. Discussions on the fiscal policy stance in the Eurozone are expected to take place in the context of the discussions on the reform of the EU’s SGP at the 5-6 December Ecofin meeting.

The general escape clause will be deactivated at end-2023. The reform of the fiscal rules must thus be adopted next year, before the summer. It may be necessary to agree not to clarify everything and to allow the Commission some flexibility in the way it applies the rules, rather than adding complexity to a reform designed to simplify the existing SGP.

An agreement on the new fiscal governance architecture would pave the way for joint issuance of EU debt (for loans) to mitigate the energy crisis. The SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) programme could serve as a model. Set up in 2020 to avoid mass unemployment following lockdowns, it has been a great success with investors and has proven very effective. It has particularly benefited the most indebted Eurozone states.