Summary

- Inflationary pressures are now everywhere: since the start of the year, inflation data has exceeded the expectations of many analysts and commentators. Annual CPI readings reached their highest level in decades in both developed (DM) and emerging markets (EM), with some variation across countries. Though fuelled by the conflict in Ukraine, which has caused disruptions across energy and commodities markets, rapid price increases are now sustained by a deeper, intrinsically psychological factor.

- Inflation and psychology: the role of collective long- and short-term memory, public reactions, and the propagation of narratives across economic agents and through the media ensures that the self-fulfilling prophecy of inflation is ultimately realised. This is a process of memory awakening and is part of the wider ‘road back to the ‘70s’ narrative.

- Role of policymakers: as policymakers are being pressed hard for protection and compensation, inflation leads to more fiscal accommodation rather than less, which ultimately causes further inflation. Monetary policy has fallen behind the curve and authorities are faced with the dilemma of fighting inflation without stifling growth.

- Investment consequences: investors are looking at real returns as the new mantra for this decade. Portfolio construction that targets real rather than nominal returns should include real and alternative assets, high dividend stocks and flexible fixed income strategies that can adapt to higher rates.

After a decade of central banks struggling to bring inflation up to target, the start of 2022 has been characterised by a shift in the inflationary environment worldwide. US inflation is at its highest level in over 40 years, with other DM trailing close behind. Eurozone annual inflation reached 7.5% in March, up from 5.9% in February and 5.1% at the start of the year. The average DM CPI at end-March was 5.6% YoY and 7.2% in EM, signalling the start of a new inflationary era. Within this context, market attention has shifted to uncovering the psychological mechanisms which underpin inflation and ensure its self-fulfilling prophecies come to pass, as the expectation of higher prices in the future reinforces the inflationary narrative. In this interview, Pascal Blanqué uncovers some of these mechanisms and explores the link between inflation and psychology.

How does psychology factor into inflation? Is inflation always a monetary phenomenon, or is it partly psychological in nature?

The two are interconnected through psychological time, whereby time flies during periods of inflation. For example, one hour in normal, non-inflationary times corresponds to one day under hyperinflation or asset price bubbles. In my books I’ve discussed the important notion of the “psychological referential” wherein powerful forces of memory and forgetfulness are at play. The idea that I have developed is that an increase in money is insufficient, albeit necessary, to trigger inflation. A shift in the psychological referential must occur simultaneously.

When does inflation shift from an economic to a psychological phenomenon and what are the warning signs? Does the transition occur gradually or is there a tipping point?

Narratives play a role in spreading inflation exponentially, like a virus, turning it into a mass phenomenon with feedback loops and self-fulfilling prophecies.

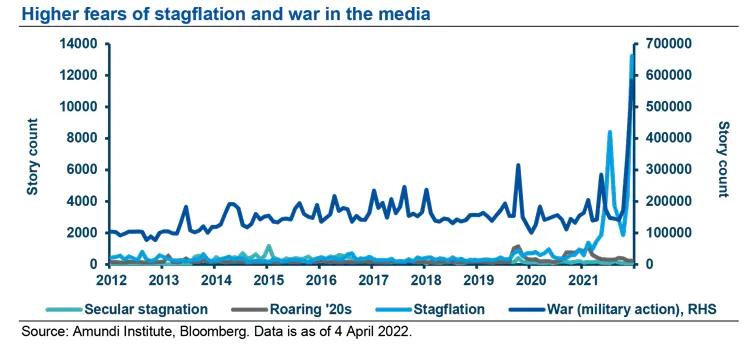

Inflation is a cumulative phenomenon. Once it has taken hold it is difficult to find a way back. Narratives play a role in spreading inflation exponentially like a virus, turning it into a mass phenomenon with feedback loops and self-fulfilling prophecies. Artificial intelligence has given us the tools to analyse these narratives: the inflation narrative has gained traction, while the secular stagnation narrative is receding. This process is central to the way expectations are formed in my view. The accumulation of data (rising prices) forms a short-term memory, which establishes a link with long-term memory (the ‘70s). Hence there is a shift from a dormant situation to an exponential acceleration. Signs of the process maturing include wage negotiations and, more generally, forces accumulating a different share of added value between labour and capital. This is an aspect of what I call a regime shift. Through an accelerating process which is exponential and self-sustaining there is inflation when people say there is inflation.

An inflation process, particularly when it starts from nothing as inflation is deeply forgotten, is a discovery process.

What does it mean for inflation expectations to become ‘unanchored’ and how do we recognise this situation?

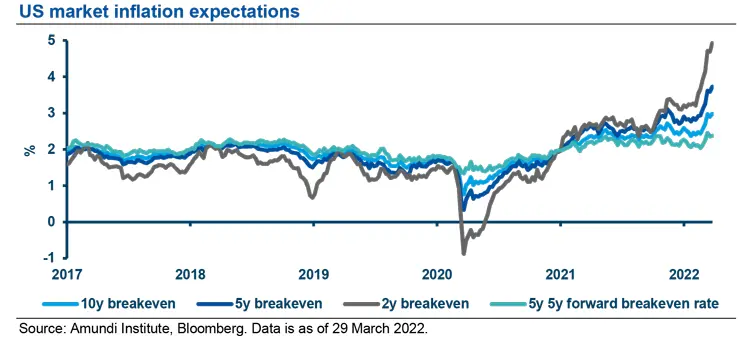

Un-anchoring is the loss of central bank credibility and a loss of control of the yield curve. It may present itself as a sudden surge in long-term rates and market-based long-term inflation measures (5-year inflation swaps, 10-year breakeven rates). Nevertheless I have my doubts about these measures, which may have been distorted by quantitative easing (QE) policies. Surveys like those carried out by the University of Michigan are more telling. My thesis is that central banks’ DNA has changed: they will err on the benign-neglect side of the equation for various reasons, such as the asymmetry between growth and inflation, fiscal dominance and the financial repression framework of negative real rates. Central banks are far behind and certainly won’t close the gap. At some point something will have to give.

What is your take on current inflation dynamics and how the public is reacting to this?

The public reaction went from ignorance and denial to surprise and acknowledgement. Now we are reaching the next level: fear. An inflation process, particularly when it starts from nothing as inflation is deeply forgotten, is a discovery process and a price for markets. Most people currently involved in economic life do not know what inflation is and have not been faced with any sustained period of rising prices and interest rates. This is a process of memory awakening and adaptive expectations. What we’ve seen from successively higher readings each month is a progressive build-up of short-term memory that brings long-term references back to the 70s or to stagflation. Loops spread as people talk, react and try to adjust. We’ve seen inflation picking up in areas not hit by bottlenecks or energy, but simply due to a viral contagion of talk, narratives and stories on TV. The spread of narratives through media (a self-fulfilling phenomenon) has created anxiety and fear. As happens in all initial inflationary sequences, social and political worries have risen rapidly, as inflation hits the poorest first, reinforcing and exposing pre-existing social divisions.

What can policymakers do to control the psychological aspect of inflation?

By publicising the presence of inflation through initiatives like ‘cheque inflation’, the existence of the threat is recognised and thereby accelerated.

The pressure on policymakers has intensified, think of Biden or even Lagarde for example. The first reaction is a demand for protection and compensation on the budgetary side through various channels, for example blocked prices, subsidies and fiscal transfers. Inflation leads to more fiscal accommodation rather than less and this in turn contributes to the dynamics of inflation through both real and psychological channels. By publicising the presence of inflation through initiatives like ‘cheque inflation’, the existence of the threat is recognised and thereby accelerated. Inflation is a self-propelling phenomenon. Another aspect is that monetary policy is always criticised for having fallen behind the curve. Policymakers are faced with dilemmas and trade-offs such as fighting inflation at the risk of killing demand, housing and growth. Raising rates on the back of supply problems cannot fix inflation while also hitting demand. A final aspect is geopolitical economics. Energy problems have ignited debates and triggered action on security and sovereignty. Many governments have been accused of naivety and lack of a geopolitical vision. Most are now changing their policies.

What role does the media play?

Economics, and markets in particular, are made of words, discourses, images and battles of narratives. A price at relative equilibrium is reached when a battle is temporarily won.

As stated above, the media is a critical element in financial and economic narratives. We, Robert Shiller and some of us, have posited that economics, and markets in particular, are made of words, discourses, images and battles of narratives. A price at relative equilibrium is reached when a battle is temporarily won. Narratives must be included in what we call ‘fundamentals’ to get a more realistic description of what we observe. The media is an accelerator of the “virus”, as it usually presents the impressively worrying side of things, in this case inflation.

How important is the collective memory of previous inflationary periods to properly assessing the current one?

This is fundamental. A large part of my work began with the idea that economic and financial phenomena cannot be understood without integrating a psychological referential structured by duration, memory and forgetfulness (i.e. psychological time). People form expectations (that is, discount the future) in the same way that they remember and forget. This is true on an individual and a collective level. I have shown that there is a collective memory made of short-term and long-term memory, structured by big core narratives which more or less correspond to reality, and framed by a coefficient of forgetfulness. The more distant in the past, the greater the coefficient; but with sudden non-linear jumps a short-term event can ignite long-term memory. I wrote a piece in April 2019 (‘the road back to the 70s’) where I made the case for a looming regime shift, highlighting common points between that era and today. It is not that history repeats itself and the phenomena are the same, but rather the psychology of people is relatively constant. People react in much the same way to comparable events. One critical reason for this is that their referential is made by a deep memory of certain major events, not always consciously as collective events form an unconscious dimension. Think of hyperinflation in Germany, the 70s, the roaring 20s, or the Spanish flu in relation to the Covid crisis. These mechanisms are valid for people and investors. The latter are now looking for a portfolio construction which targets real rather than nominal returns. Real and alternative assets, high dividend stocks and flexible fixed income strategies will benefit from higher rates and will see strong demand growth in the search for real returns, which has become the new mantra.

Works by Pascal Blanqué include:

- Blanqué, P. (2010), Money, Memory and Asset Prices, Paris, Economica (distr. Brookings Institution).

- Blanqué, P. (1st ed. 2014) (2nd ed. 2016) (3rd ed. 2019), Essays in Positive Investment Management, Paris, Economica (distr. Brookings Institution).

- Blanqué, P. (2018), The Economic and Financial Order, Paris, Economica (distr. Brookings Institution).

- Blanqué, P. (2019), The Road Back to the 70’s. Implications for Investors, Amundi Insights Paper, June.

- Blanqué, P. (2020), Pure Theory of Economic Time. Rovelli-simonian meditations, Paris, Economica.

- Blanqué, P. (2020), Covid-19: The Invisible Hand Pointing Investors Down the Road to the 70’s, Amundi Insights Paper, May.

- Blanqué, P. (2021), Ten weeks into Covid-19. Psyche, Money and Narratives. An interpretation of the crisis, Paris, Economica.

- Blanqué, P. (2021), Do Not Give Up on Fundamental Valuations, Amundi Insights Paper, May 2021.

Definitions

- Beta: Beta is a risk measure related to market volatility, with 1 being equal to market volatility and less than 1 being less volatile than the market.

- Drawdown: The peak-to-trough decline during a specific record period of an investment, fund or commodity, usually quoted as the percentage between the peak and the trough.

- Quality investing: It aims at capturing the performance of quality growth stocks by identifying stocks with high return on equity (ROE), stable year-over- year earnings growth, and low financial leverage.

- Value style: It refers to purchasing stocks at relatively low prices, as indicated by low price-to- earnings, price-to-book, and price-to-sales ratios, and high dividend yields. Sectors with dominance of value style: energy, financials, telecom, utilities, real estate.