Post-war Second World War pension funds were developed on the basis of two different logics: the Bismarckian (defined contributions) in Germany and the Beveridgean system (defined benefits) in England. Today, there are hybrids of these systems but all have established minimum pension levels or social minimums.

Reforms have led to the development of funded pension systems alongside the pay-as-you-go (PAYG) systems, where active workers’ contributions pay for pensions of retirees, as seen in France, and funded systems, where contributions are accumulated in pension funds that invest in financial securities for future benefits. There is no longer a typical pension system as each country has its own specific features and various degree of complexity.

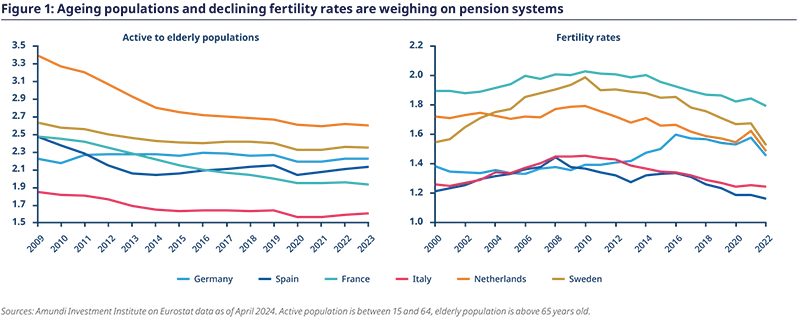

Since 1980, the Eurozone has been grappling with significant demographic challenges due to an aging population, which has increased the financial demands on pension systems, particularly in countries using PAYG models. This demographic shift is primarily driven by declining birth rates and rising life expectancy (Figure 1). Additionally, the COVID-19 crisis has further exacerbated fiscal deficits and public debt, leading to increased pension expenditures across the region.

Historically, countries such as Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and Sweden have faced significant demographic challenges and implemented various reforms to stabilize their pension systems. Key reforms include:

– Raising the Official Retirement Age: Sweden has gradually increased the retirement age to 66, while Germany is raising it to 67 to align with rising life expectancy.

– Extending the Contribution Period: Spain has lengthened the required contribution period from 35 to 37 years, requiring workers to contribute longer for full pension benefits.

– Adjusting Pension Calculations: Countries like Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands have incorporated demographic factors into pension calculations, recalibrating benefits based on the worker-to-retiree ratio, which may lead to lower pensions as the population ages.

– Increasing Contribution Rates: Spain has raised contribution rates from both workers and employers to enhance the pension system's financial sustainability amid a growing retiree population.

To enhance retirement security, several countries have encouraged private pension savings through tax incentives and employer sponsored plans, thereby reducing reliance on PAYG systems. In hybrid models, where PAYG pensions may fall short, individuals are motivated to invest in employer-sponsored plans and personal savings. Overall, these measures aim to adapt pension systems to the realities of an aging population by creating a more hybrid approach that combines PAYG with additional investments from employer plans and personal savings. This strategy seeks to ensure long-term sustainability and provide adequate support for retirees.

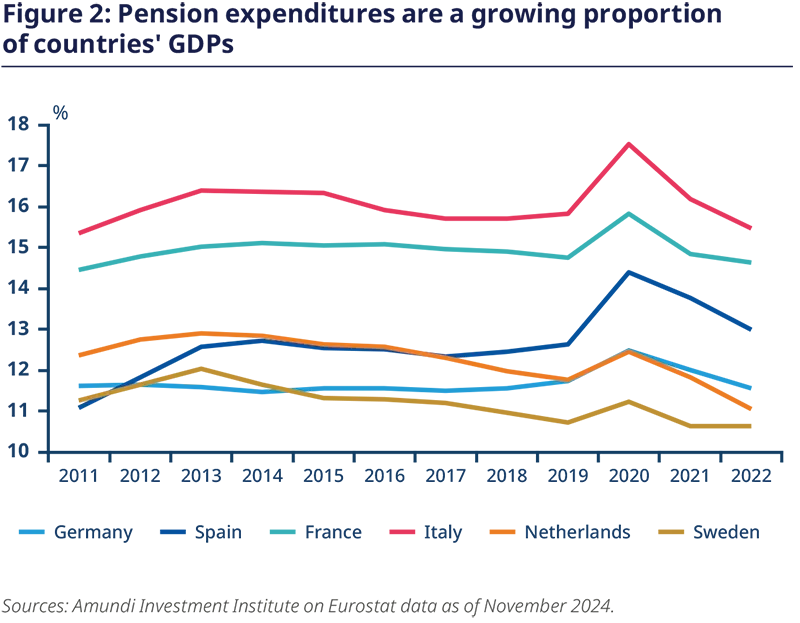

Pension spending on PAYG systems constitutes a significant portion of government expenditure, particularly in France and Italy, where it accounts for 14.7% and 15.5% of GDP respectively, compared to an overall European average of 12% (Figure 2). Sweden and the Netherlands have lower proportions at 10.7% of GDP. The sustainability of these systems is a concern, as they rely on intergenerational solidarity, requiring a sufficient number of workers to maintain the balance.

A decline in the working population or real wages can disrupt this equilibrium, leading to deficits. PAYG systems are rarely ‘pure,’ meaning contributions and benefits often do not balance. Pensions may be adjusted for social reasons, and these systems typically depend on taxes and subsidies. An increasing dependency ratio—where retirees outnumber workers—can strain financial sustainability, resulting in lower replacement rates or higher contribution rates. Currently, the Netherlands and Sweden have the lowest deficits at 0% (Figure 3), followed by Germany at 2%. In contrast, France, Spain, and Italy face higher deficits of 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively. Countries like the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden are noted for their effective pension management.

A 2023 study by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) assessed the fiscal capacity of governments to finance pensions, revealing that France and Italy have the least fiscal leeway to counter rapid declines in pension levels, while Germany and Spain are in a slightly less critical position. To alleviate the fiscal burden of first-pillar pensions, the German government has proposed a state-funded pension plan aimed at reaching EUR 200 billion by 2036, financed through government loans and additional federal assets. Meanwhile, Sweden, despite having a balanced pension system, faces poverty issues among retirees, particularly affecting women, who receive pensions that are, on average, 30% lower than those of men, highlighting the intersection of income inequality and pension replacement rates.

The room for manoeuvre to finance public pensions varies significantly between countries. Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain pension space ranged between 10 and 25% while Belgium, Austria, France and Italy have less than 10% pension space. France and Italy especially are expected to have no pension space by 2030. While pension sustainability based on funding is one way to approach the subject, to take complete generational equity into account, it is also important to consider life expectancy and years remaining in good health in determining the sustainability and fairness of pension systems (Figure 4).

The emergence of hybrid pension systems in the Eurozone highlights the necessity for individuals to find alternative ways to finance their retirement alongside the traditional PAYG model. While PAYG systems provide essential support for retirees, the increasing financial demands due to demographic changes, such as an aging population and declining birth rates, make it clear that relying solely on PAYG is not sufficient. Countries are starting to recognise the importance of integrating funded pension schemes and, encouraging private savings to create a more sustainable retirement framework. This hybrid approach not only complements the existing PAYG systems but also empowers individuals to take control of their financial futures.

Motivating people to invest and save for their retirement is a major challenge and has significant implications for both individual outcomes as well as economies at large. Although pension systems vary significantly across Europe, challenges faced are similar and solutions are not clear-cut. Across all 3 pillars of the pension system, increasing awareness of the importance of investing for retirement will be key.

Read more