Summary

Key Takeways

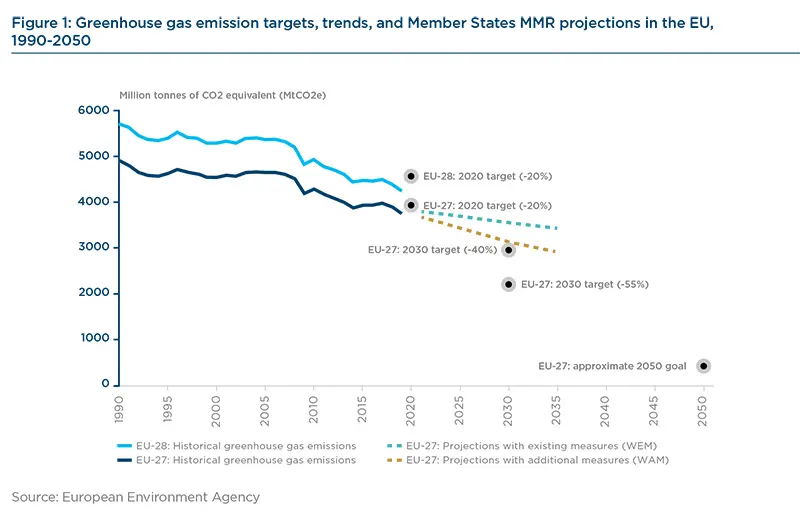

- In June 2021, the EU Commission adopted the “EU Fit for 55” package, a set of policies to reach the bloc’s objective of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 versus 1990. With existing measures, the EU’s carbon emissions are expected to fall 36% only below 1990 levels.

- The European Commission’s plan relies on four pillars:

- a more pronounced industrial transformation, with a wider application of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to new sectors, along with a tightening of the ETS itself;

- a faster transition to clean mobility;

- a marked growth of renewable energies and energy efficiency;

- the restoration of natural ecosystems and forestry to absorb carbon from natural sinks.

- If in the medium- and long-term, the advantages of the transition are clear, climate policies risk putting extra pressure on the most vulnerable people in the short-term. To respond to this, the Commission proposes the establishment of a new Social Climate Fund, with an envelope of €144.4bn, financed by the EU budget.

- However, the ambition of the package will face obstacles to implementation. A lengthy and arduous legislation process, jointly with uncertain international acceptance, are some of the difficulties that can threaten implementation.

Introduction

The EU formally adopted in June its new objective of cutting the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 versus 1990. This represents a substantial increase in the bloc’s ambition compared to the previous 40% reduction target and sets an interim target close to the range of domestic emissions reductions of 58-70% deemed consistent with the Paris Agreement by Climate Action Tracker. As such, this objective places the European Union as a leading region on climate change mitigation efforts.

However, with existing and planned measures, the EU’s carbon emissions are expected to fall only 36% below 1990 levels by 2030. The new target therefore required to strengthen and extend climate policies. This is the very purpose of the “Fit for 55” package: a comprehensive list of policies proposed by the European Commission on 14 July, 2021 to achieve its greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 55%.

The Commission has conducted impact assessments before presenting these proposals to measure the opportunities and costs of the green transition. In September 2020, a comprehensive impact assessment showed that the 55% emissions reduction target by 2030 is both achievable and beneficial.

These proposals are also aligned with the EU’s recovery plan, which dedicates unprecedented resources to support a green and fair transition as economies emerge from Covid-19. The EU continues to focus on unlocking investment to finance a sustainable and inclusive recovery1, while the NextGenerationEU tool will contribute at least 37% to the green transition2.

The objectives set out by the Commission’s proposals are multiple. First, the package aims to set a more ambitious and costeffective path to achieving climate neutrality by 2050. It is also aligned with the objective to continuing the EU’s track record of cutting greenhouse gas emissions, whilst growing its economy and creating decent green jobs. Finally, this set of proposals should encourage international partners to increase their ambition to limit the rise in global temperature to 1.5°C.

All in all, “Fit for 55” constitutes a key milestone for the European Union on the road to Glasgow. It will be the backbone of the EU’s delivery on its commitments to fight climate change, as laid down in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

1) A set of ambitious proposals to reach net neutrality in a socially equitable way

The Commission’s plan is composed of a series of legislative proposals setting out the European Union’s trajectory to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

The package proposes to revise European climate legislation, including: the application of emissions trading to new sectors and a tightening of the existing EU Emissions Trading System; measures to prevent carbon leakage; new requirements for industry to decarbonize production processes; a faster roll-out of low emission transport modes and the infrastructure and fuels to support them; increased use of renewable energy; greater energy efficiency; an alignment of taxation policies with the European Green Deal objectives; and tools to preserve and grow our natural carbon sinks.

1.1 Industrial transformation and carbon pricing

To meet emissions reduction objectives set by the European Commission, EU industry will need a coherent regulatory framework, access to adapted infrastructure and support for innovation to develop clean technologies.

The proposals included in “Fit for 55” are thus meant for industries to decarbonize their production processes, while seizing the multiple opportunities offered by the green transition.

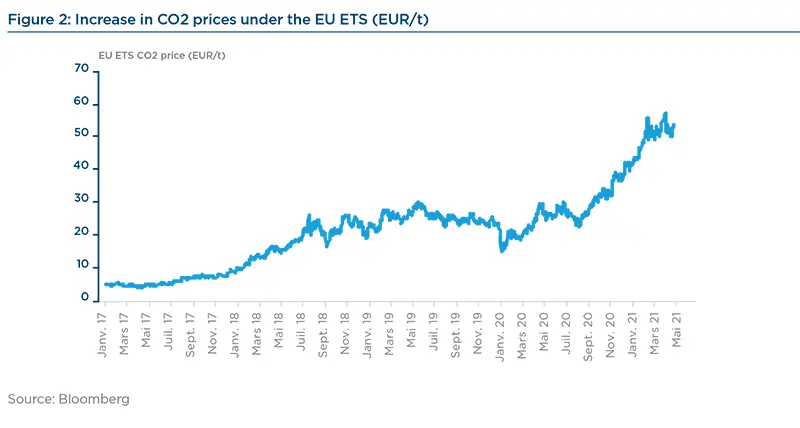

The Commission has assessed the possibility of reinforcing emissions trading as a tool to achieve greenhouse gas emissions reductions in the European Union. The proposal includes an extension of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to include emissions from maritime transport over the 2023-2035 period. Enhanced efforts will also be required from aviation operators: the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) will be implemented through the EU ETS Directive. Emissions trading in the road transport and building sectors will also be applied from 2026 onward to increase incentives to supply cleaner fuels to the market.

To complement the spending on climate in the EU budget, the Commission’s proposal suggests that Member States spend the entirety of their emissions trading revenues on climate and energy-related projects. Moreover, a dedicated part of the revenues from the new system for road transport and buildings should address the possible social impact on vulnerable households, microenterprises and transport users.

Moreover, a new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will set a carbon price for imports of certain products based on their carbon content. Specifically, importers of iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminum and electricity will be required to pay this CO2 import tax from 2026 onwards. This carbon tax mechanism at the EU’s borders aims to ensure that European emission reductions will contribute to global emission reductions and not push carbon-intensive production beyond Europe’s borders, i.e. cause “carbon leakage”.

The EU Innovation Fund, which supports businesses and SME investments in clean energy will increase its financing capabilities to finance innovative decarbonization projects and infrastructure.

Attention will be given specifically to projects in sectors covered by the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

The Commission takes into account the fact that Member States have national specificities and different starting points. Thus, the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) assigns each Member State particular emission reduction targets for buildings, road and inland shipping, agriculture, waste and small industries. These national targets are based on GDP per capita and adjusted for cost-effectiveness. Overall, the Commission’s proposal should deliver an EU-wide emission reduction of 40% from the aforementioned sectors by 2030, compared to 2005.

Overall, the industrial transition must be a collective and inclusive effort, co-designed with industrial ecosystems across Europe. This is why the amended Industrial Strategy includes the creation of transition pathways with social partners and other stakeholders to identify the scale of the needs, including reskilling, investment and technology needs. Priority will also be given to sectors most impacted by the Covid-19 crisis, such as the mobility, construction and energy industries.

1.2 Clean mobility

On top of carbon pricing, the Commission is proposing new measures to reduce emissions from transport, which represents almost a quarter of the EU’s total greenhouse gas emissions and is the most important source of air pollution across European cities3.

To encourage a faster deployment of lowemission transport modes, the Commission proposes stricter CO2 emission standards for cars and vans, thereby reducing average new vehicle emissions by 55% from 2030 and by 100% from 2035, compared to 2021 levels. This measure is complemented by the amendment of the regulation on the deployment of Alternative Fuels Infrastructure, which will require Member States to increase their recharging capacity in line with the ambition to increase the sales of zero-emission vehicles. It will require governments to install recharging and refueling points at regular intervals on major roads: every 60 kilometers for electric recharging and every 150 kilometers for hydrogen refueling. These measures are meant to reinforce and complement each other: putting a price on carbon for road transport will make the existing fleet drive cleaner, and setting more ambitious CO2 standards will help to get more zero emissions vehicles on the road by 2030.

Amendments to air transport regulation are also included in the Commission’s proposals. The ReFuelEU Aviation Initiative will compel fuel suppliers to increase the share of sustainable aviation fuels into existing jet fuel uploaded at EU airports. A zero emission aviation Alliance, which should emerge at the end of 2021, will complement these efforts to ensure the market is ready for disruptive clean technologies. Then, the FuelEU Maritime Initiative will encourage the use of sustainable maritime fuels and zero-emission technologies by imposing a maximum limit on the greenhouse gas content of the energy used by ships arriving at or departing from EU ports.

1.3 Energy

To reach the EU’s 2030 target and eventually climate neutrality, the Commission is proposing an increased use of renewable energy, with a proposal to amend the 2018 Renewable Energy Directive. This change intends to raise the production target so that the share of energy produced from renewable sources reaches 40% by 2030, up from the current 32% level. To reach this overall goal, specific targets are proposed for renewable energy use in transport, heating and cooling, buildings and industry.

The Commission also wishes to improve energy efficiency through the recast of the Energy Efficiency Directive that will set a more ambitious binding annual energy reduction target at the EU level. It will notably double the annual energy savings obligation for Member States and will require the public sector to renovate 3% of its buildings each year to drive national efforts. This should lead to a 9% reduction in energy consumption by 2030, compared to baseline projections4.

Then, a revision of the Energy Taxation Directive is set to align the minimum taxation for heating and transport fuels with EU energy and climate policies. This will be done through the promotion of clean technologies and the removal of outdated tax exemptions and other incentives that currently encourage the use of fossil fuels.

1.4 Counting on forestry

The fight against climate change is closely linked to the preservation of biodiversity, and both crises cannot be treated separately. Notably, restoring nature and enabling biodiversity to thrive are essential to help land and ocean ecosystems fulfil their crucial role of carbon absorption and storage.

The updated Regulation on Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry sets a more ambitious EU target to absorb carbon from natural sinks, equivalent to 310 million tons of CO2 emissions by 2030.

Specific national targets will require Member States to care for and expand their carbon sinks to meet this goal. By 2035, the EU should aim to reach climate neutrality in the land use, forestry and agriculture sectors.

Finally, the new EU Forest Strategy aims to improve the quality, quantity and resilience of EU forests, setting out a plan to plant three billion trees across Europe by 2030.

Together with the forthcoming New Soil Strategy, EU Nature Restoration Law and Carbon Farming Initiative planned for later in 2021, these laws will contribute to strengthening the EU’s natural carbon sinks and support the social and economic functions of forestry and forest-based sectors.

2) Ensuring a socially fair transition:

While in the medium - to long-term, the benefits of EU climate policies clearly outweigh the costs of the transition to low-carbon economies, climate policies risk putting extra pressure on vulnerable households, workers and communities in the short run.

To fairly spread the costs of tackling and adapting to climate change, the European Commission proposes the establishment of a new Social Climate Fund. Its main objective is to support citizens most impacted by energy and mobility poverty. In the European Union, energy poverty alone affects up to 34 million people5. As a result, the fund will provide dedicated funding to Member States to help citizens finance investments in energy efficiency, new heating and cooling systems, and cleaner mobility.

The Social Climate Fund will be financed by the EU budget, using an amount equivalent to 25% of the expected revenues of emissions trading for building and road transport fuels. Moreover, it will provide €72.2 billion of funding to Member States, for the period 2025-2032. With a proposal to draw on matching Member State funding, the Fund would mobilize a total of €144.4 billion for a socially fair transition.

An amendment to the Own Resource Decision and the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027 will be proposed by the Commission to accommodate this new instrument. In addition, the Commission intends to lay down further guidance to Member States through a proposal for Council Recommendation on how to address the social aspects of the climate transition. The functioning of the Social Climate Fund will be assessed in 2028, particularly in light of the effects of the Effort Sharing Regulation and the extension of emissions trading to new sectors.

3) Potential obstacles to implementation

The set of proposals included in the Commission’s “Fit for 55” package are ambitious, and therefore obstacles to implementation remain.

To start, the legislative process to move along with these proposals will be long. The negotiation process with EU lawmakers – the EU Parliament and the EU Council – can take roughly two years.

Where possible, existing legislation such as the Renewable Energy Directive is made more ambitious, and where needed, new proposals are put on the table. While the European Parliament will not be renewed before 2024, presidential and federal elections will be held in France and Germany respectively over the next 12 months, creating uncertainties on future climate leadership.

Moreover, just like for all tax-related matters in the EU, changing the Energy Taxation Directive will require unanimity at the EU Council.

Then, despite the creation of a Social Climate Fund, social acceptance risks are likely to trigger fierce debates. Specifically, the revision of the Energy Taxation Directive, the extension of the emissions trading scheme and the application of a carbon price on transportation and heating fuels create the risk of placing a disproportionate cost burden on low-income households. For example, a CO2 price of €55 per ton would increase domestic gas prices in Germany by 17%6.

Lastly, while this policy package demonstrates the European Union’s role to lead by action and example in the fight against climate change, it cannot alone deliver the global emission reduction the planet needs. The Fit for 55 package is therefore a way to call upon governments around the world to work together to increase global climate ambition and deliver objectives set by the Paris Agreement. However, international acceptance is uncertain and generates a strong risk to implementation. The CO2 import tax through the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will likely lead to frictions with key commercial partners. As a reminder, back in 2013, the European Union eventually had to limit the scope of its carbon market for airlines to intra-EU flights, following strong backlash from other countries7.

Conclusion

To conclude, the Fit for 55 package offers landmark strategies on biodiversity, circular economy, zero pollution, sustainable and smart mobility, energy renovation and many others. It is meant to ensure that efforts to lead the fight against climate change are shared between Member States in the most cost effective way. It also guarantees support to populations most in need, to make sure that the transition reaches everybody in a beneficial way.

The EU needs to implement its policy toolbox as soon as possible to meet 2030 targets and set the continent on the road towards climate neutrality by 2050. As a next step, the European Parliament and the Council are to begin their legislative work on the proposals, ensuring that they are treated as a coherent policy package.

_____________________________________________

1. European Commission, Strategy for financing the transition to a sustainable economy, July 2021

2. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_2397

3. European Commission https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/transport_en

4. Energy Efficiency Directive, 2020 Reference scenario baseline

5. “Fit for 55 delivering EU’s 2030 climate targets” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0550

6. The EU’s Fit for 55 Package - Key takeaways from Bernstein Renewables, Chemical, Airlines & Energy teams

7. Politico (2013) “EU offers retreat on aviation emissions” https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-offers-retreat-on-aviation-emissions/