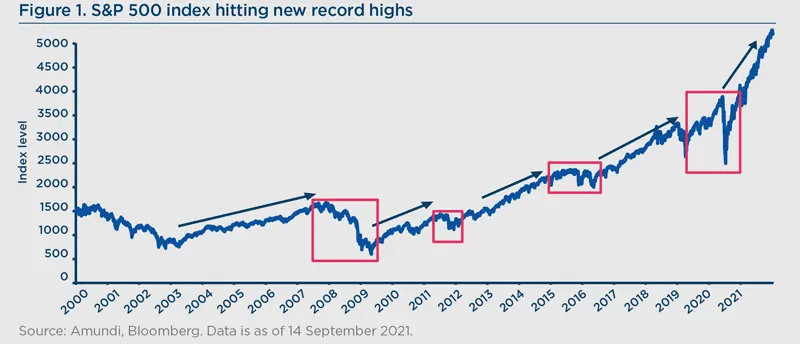

Investors have enjoyed stellar performances over the last twelve months. A 60/40 traditional global equity/bond portfolio1 returned around 19% on a one-year horizon, well above even the rosiest expectations of the recovery from the Covid-19-induced slump. The S&P 500 is up +100% from last year’s bottom – an iconic figure that says a lot about the buoyant market sentiment.

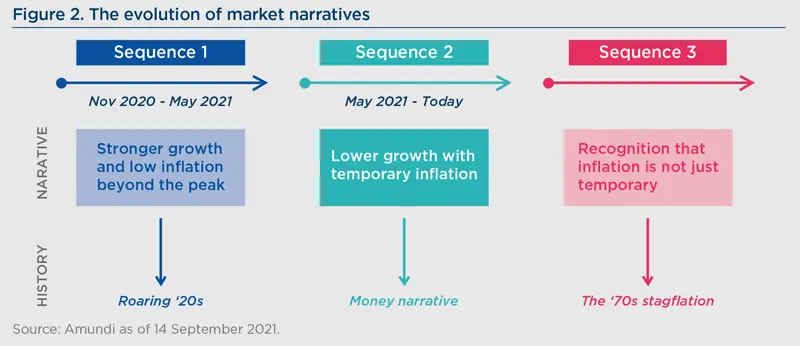

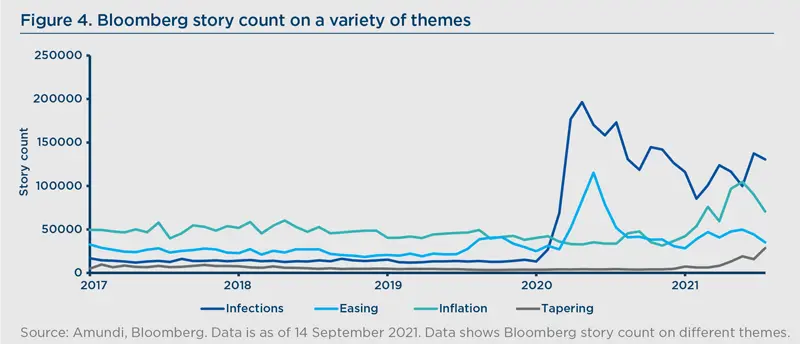

At this time of year when we go back to school, market uncertainty is rising not only because of recent news about the Covid-19 Delta variant, but, more importantly, because new elements are emerging in the battle of the narratives underpinning financial markets. One narrative becomes dominant until a new one challenges and then eventually replaces it, triggering a regime shift. As narratives are connected with expectations, they play a critical role in shaping valuations, their equilibrium, and their excesses.

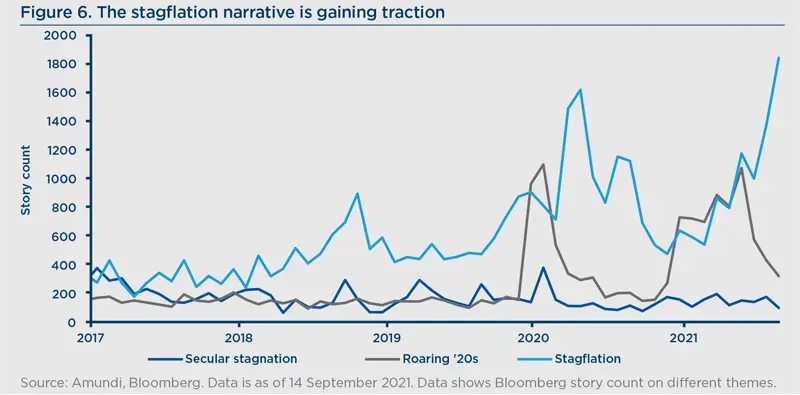

So far this year, we have seen the continuation of the never-ending monetary umbrella narrative, coupled with the great recovery lifting risk assets. The euphoria around this exceptional rebound in growth has led to the idea of a more structural economic and earnings boom propelled by the technological advances that accelerated during the Covid-19 crisis (somewhat mirroring the experience of the ‘Roaring Twenties’). No doubt, the battle of narratives will see a winner forming a fresh new consensus, through a sort of discovery process, around the key question: what will be left of the consensual rebound in activity and inflation?

The first sequence was characterised by the Goldilocks narrative of stronger growth at trend and low inflation beyond the peak and has now ended. The rapid emergence of competing narratives has focused attention on the weaknesses of the previous assumptions and on the cracks around the basement walls. The narrative of inflation that resurfaced in the first part of the year and lifted bond yields higher in the spring has now receded amid the revenge of monetary dominance narrative, with the Fed’s view of a temporary rise in inflation being taken for granted by markets.

Doubts are now materialising on the growth front, challenging the current narrative of the great recovery mirroring the booming 1920s. The great expectations regarding technological change and their associated productivity gains are fading, meaning current market valuations will start to look barely sustainable. This should sound a wake-up call for investors. “A more temporary than expected” growth rebound is on the cards. The overall economic picture will remain good at a global level, but the direction, which matters most for investors, will point to a deceleration from the exceptional figures we have seen in the first part of the year. While markets were pricing in higher growth and temporary inflation at the start of the summer, they are shifting to pricing in “lower growth with temporary inflation”, revamping expectations of central banks’ dovishness.

Persistent higher inflation

We may now be just one narrative change away from the next big move, which will be the recognition that inflation is not just a temporary shift, but more structural than the market is currently pricing in. This will awaken the stagflationary ghost (lower growth coupled with higher inflation at trend). Although this scenario does not appear to be immediately around the corner, it is important to note that investors have not faced such a combination since the 1970s and they should start preparing for it, in our view. Market reactions can be confused, during a process of expectation adjustment which will not be linear. Experience suggests they will offer little comfort.

Currently, rising inflation is mainly seen as consequence of the economic re-opening and therefore perceived as temporary. The temporary element may fade alongside the deceleration of global growth, but other structural inflationary forces will remain in place and take the lead in the process of price formation. Global supply chain disruption will take years to be repaired, shipments remain constrained and freight costs are skyrocketing. Climate change is likely to put continued pressure on commodities linked to the green transition, on food commodities (harvest and forest disruption) and on the transportation industry which has to embark on a transformation process to reduce emissions.

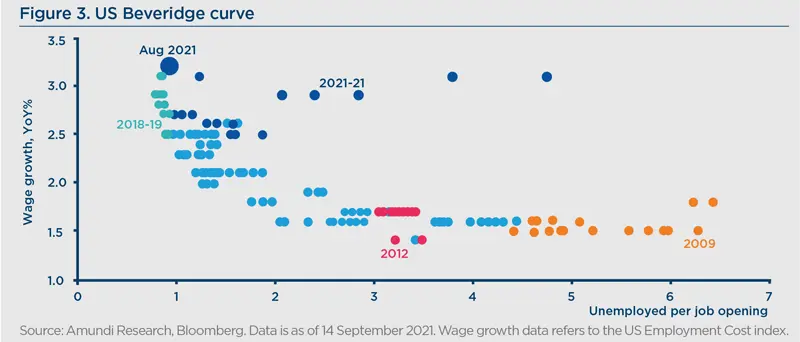

Wage growth has remained contained, but pressures are mounting, despite the slack in labour markets (compared to February 2020, 5.3 million jobs are still missing in the United States as of August 2021). Real disposable income is falling: the higher level of prices set during the spring will not come down. Wage negotiations are likely to push for an upward review at a time when the number of unemployed per jobs openings are declining (see figure 3). The secular trend of falling wages as a share of national income in favour of profit is coming to an end, just when the consensus in favour of higher corporate taxation is growing.

China will be another element shifting the pendulum towards persistent higher inflation. In recent decades China exported deflation, through cheap and low-wage manufacturing. Shifting demographics, alongside a falling working age population, are pointing to a smaller supply of cheap labour. Shortages and higher relative wages are pointing to higher prices, not lower. In the next decade, China is likely to add to the reversal of disinflationary trends.

Central banks’ big shift

Central banks are the actors to watch in the battle of the narratives, as they are trapped in the cycle of growth-virus dynamics -- which push for an easing stance -- and the inflation dilemma, leading to an increased focus on tapering. They are walking a tightrope of trying to balance these two forces.

On one side, the risk is of a premature withdrawal of exceptional monetary accommodation. This could be justified by some indicators (e.g., the real estate market is getting hot in the United States), but may compromise the recovery of the job market and come at the wrong time, for example just when the economy is losing steam. On the other side, there is a risk of not leaving any room for manoeuvre during future emergency situations and remaining stuck with all the engines already up and running (quantitative easing, ultra-low or negative interest rates) just when inflation is going to prove more structural than expected.

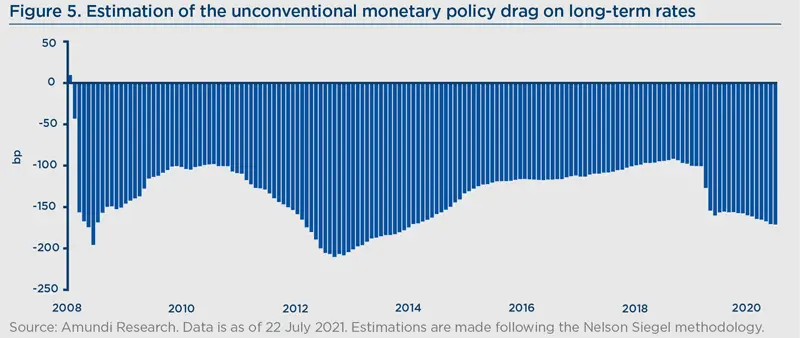

Among these contrasting forces, we believe that the path for policy normalisation is narrow at this point. The risks regarding growth are likely to weigh more than the risk of inflation on central banks’ reaction function. Tapering will be gradual (e.g., on mortgage bonds amid real estate excesses), but overall the tone should remain very dovish to avoid any tightening of financial conditions which could harm growth. The recent Jackson Hole meeting confirms this view. In the narrative of decelerating growth momentum and transitory inflation, at some point we will see the consensus mount for more rather than less policy accommodation, at a time when a significant dose of fiscal accommodation will still be in place.

This is consistent with a regime shift away from the rule-based system that has characterised recent decades (inflation as an obsession for central banks and fiscal discipline at the budgetary level). Central banks’ tolerance for higher or overshooting inflation -- especially in the ‘transitory’ narrative -- is the consequence of this. The next sequence is the nastier one. Once inflation proves to be less temporary than expected and growth slows down, it will deny the roaring ‘20s productivity miracle. What has been anchored as a certainty in the previous regime (inflation expectations) will no longer be rock-solid. This sequence will challenge the credibility of central banks and their independence. We are not there yet, but the challenge will come, with increasing uncertainty on the interest rate trajectory and consequently on risk asset valuations.

Investment implications

We see three main consequences for investors following the sequences outlined above.

1. There is no smart alternative to equity. Confidence in central banks remaining on the dovish side has been pushed to extremes, with bond and equity valuations beyond that which can be justified by long-term trends in growth, inflation, and earnings. This could make the market vulnerable after the steep bull market. Once it becomes clearer that current margin growth is unsustainable and that not all companies will be able to pass higher input costs on to consumers, the profit outlook will become less benign. However, in the transition to the new regime, central banks will buy time by putting a de-facto cap on nominal bond yields despite strong inflation figures.

This artificial disconnect between fundamentals and valuations in the bond space is welcome from many parts:

- From governments, because it makes the huge amount of debt sustainable, as long as nominal rates remain lower than growth-inflation dynamics (so-called financial repression2).

- From corporate, that can keep refinancing debt at low rates – many of them can survive in a zombie status without major challenges.

- From risk asset investors, because the low level of yields supports risk assets, in a kind of ‘no alternative game’ in which relative value reigns supreme.

As with a zero-sum game, savers and bond investors will pay the cost of it. There is no alternative for investors, both institutional and retail, to increase structurally their allocation to equities and real assets (directly or through multi-asset products) to obtain exposure to growth and avoid the erosion of nominal capital. In this respect, asset managers have an important role to play in engineering solutions that provide exposure to the engines of future expected returns, but, at the same time, reduce market timing risk (i.e., a gradual approach for retail investors) and hedge against adverse scenarios that could materialise during a regime shift. Also, the selection of businesses in equity (and credit) that can withstand rising inflation will be a key theme moving forward.

However, the fact that equities offer good relative value over bonds does not tell the whole story. The fascination of relative value, from investors simultaneously giving up on absolute valuations, will appear as a sign of a bubble pointing to changing times (transitioning to a new regime).

2. Short duration is a structural, not tactical call. The rise in Treasury bond yields in the first part of the year -- which has discounted the roaring ‘20s and recovery narrative -- has been followed by a new period of falling bond yields reflecting the transitory inflation story and, more recently, expectations for a cooling down of the recovery. The next stagflationary sequence is not priced in the market and will lead to a rise in bond yields, although probably less than that justified by fundamentals as the demand for liquid and safe assets remains very high and the supply scarce. This calls for a cautious approach to duration as a strategic view, as the main fixed income benchmarks now have a duration problem and a small change in interest rates could trigger a material loss for investors. This does not mean that we cannot see tactical adjustments on duration down the road, for example during phases in which expectations for central bank action mount amid an economic slowdown. However, as we expect to head towards a higher inflationary regime, a cautious duration view is warranted.

3. Frequent market gyrations will accompany adjustments to a new market regime. The transition to a new market regime will not be smooth amid growth and inflation dilemmas. Not all areas will follow the same deceleration path: China is already in a deceleration phase, after months of tightening. The United States will follow, while Europe will still enjoy positive surprises for a one or two quarters more, especially among the periphery nations thanks to fresh money from the EU recovery plan and a still dovish ECB stance. Emerging markets have significant differences among them. These divergent paths in economic momentum -- and consequently in policies -- will underpin relative value opportunities in the coming months. Tactical adjustments on duration and risk allocation will become more frequent, making the case for ETFs as efficient tools to rebalance allocations quickly. For playing adjustments in growth-inflation patterns, currencies will be an important tool for investors to add value to portfolios in a world of stretched bond and equity valuations.

In conclusion, in the battle of narratives, a reordering of bond and equity risk premia is the minimum investors should expect from a regime shift. Central banks are likely to remain dominant in the coming months, supporting the relative value game of the equity versus bond story. A time of structural de-risking has not arrived yet. At the same time, the illusion of a structural shift in productivity is fading, while the stagflationary narrative is resurfacing, similar to the ‘70s. The latter is likely to gain traction in the years to come, challenging both the expensive absolute equity and bond valuations. In that environment, it will be a matter of risk reduction, searching for uncorrelated sources of returns and real assets, which can withstand the stagflationary storm.

_______________________________

1The Bloomberg global equity:fixed income 60:40 index is designed to measure cross-asset market performance globally. The index rebalances monthly to 60% equities and 40% fixed income. The equities and fixed income indices are represented by the Bloomberg Developed Markets Large & Mid Cap Total Return Index and the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index, respectively.

2Low nominal interest rates help reduce debt servicing costs, while a high incidence of negative real interest rates liquidates or erodes the real value of government debt.