Summary

Introduction

The Covid-19 crisis is exceptional in many ways. It is the most serious health crisis since the Spanish flu a century ago. This crisis resulted in an unprecedented contraction of activity in 2020 and in the deepest global recession since World War II. However, this recession has been the shortest and was not accompanied by a financial crisis thanks to fiscal and monetary policy responses, which have cushioned the economic shock. The exceptional measures put in place aim to buy the time needed to emerge from the health crisis.

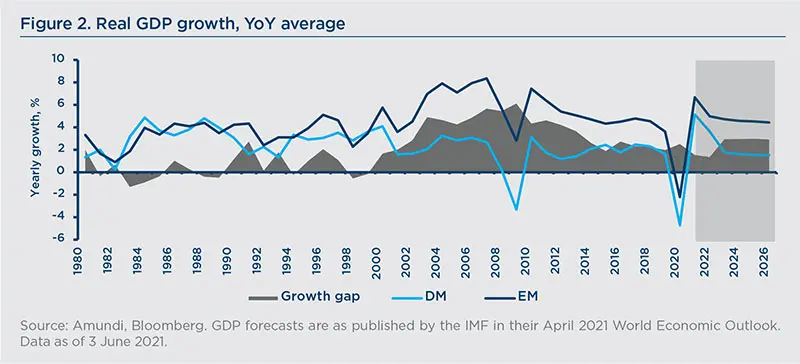

The pandemic is not over yet, and is not even under control in many countries, especially in emerging market (EM) economies. However, the ongoing vaccination campaigns are paving the way for a recovery, at least in most developed economies (DE). Uncertainty about the global economic outlook remains high, mainly due to the evolution of the pandemic. After an estimated contraction of 3.3% in 2020, the IMF expects global GDP to grow at 6.0% in 2021, moderating to 4.4% in 2022. Real GDP growth has been revised upwards since the beginning of the year thanks to additional fiscal support in some major economies and the (expected) success of the vaccination campaigns.

Global growth is expected to moderate in the medium term, due to lower supply potential and ageing populations (lower working-age population growth) in both DM and EM economies. History has taught us that major pandemics leave deep scars on the economy. Thanks to the unprecedented policy mix, the Covid-19 crisis should leave fewer scars than the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in advanced economies. This may not be true in emerging economies, which have been hit harder than advanced ones.

The absence of a financial crisis does not mean that the foundations are strong. The Covid-19 crisis has damaged significantly the global economy. Economies have become more fragile. Output losses have been particularly large for countries that rely on tourism and commodity exports and for those with limited policy space to respond. Inequalities have increased: young people, low-skilled workers, and women have been particularly affected, especially in emerging economies where an additional 95 million more people fell below the extreme poverty line in 2020. Income inequality has increased in both advanced and emerging economies.

As a result, the balance sheets of households, companies and governments have deteriorated on a global scale. Even without a financial crisis, these developments may require restructuring and recapitalisations in the medium term, which may be costly for both governments and taxpayers. Since the onset of the pandemic, governments have relied on expansionary monetary and fiscal policies to offset the sharp declines in economic activity associated with widespread lockdowns and containment measures. DE had a decisive advantage in their ability to respond.

The measures have provided relief to households facing declining incomes, as well as to businesses, particularly in the service sectors subject to lockdowns. Credit conditions have remained artificially accommodative. However, these support measures will have to end eventually. An early tightening of credit conditions could have a severe impact on small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and on low-income households, which could dampen the prospects for economic recovery. Many emerging markets have already reached the limits of what their monetary policy can do.

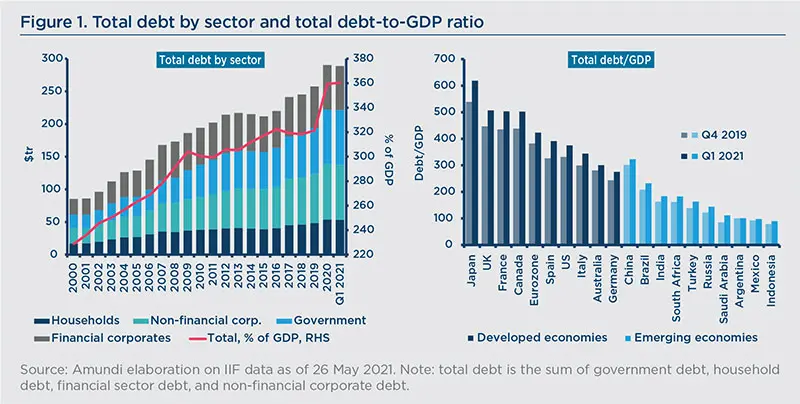

The high level of corporate debt in the run-up to the pandemic may amplify the balance sheet problems of the financial sector. In the United States, China, and some European countries, companies are highly leveraged. The sharp increase in dollar-denominated corporate debt is undermining emerging economies. It will take time to repair balance sheets. There will be a long period of deleveraging ahead with banks being more cautious in their lending.

Many questions are unanswered, especially since uncertainty remains high. When should governments stop supporting their economies? When should central banks (CB) abandon their zero or negative interest rate policies or their quantitative easing (QE) measures? How should authorities ‘accompany’ the changes brought about by the crisis? How high can public and private debt levels rise? Will inflation come out of the crisis? If so, how will central banks react? Finally, on a structural note, how can governments correct the inequalities that have increased with this crisis and how can they make growth more inclusive?

The short-term outlook remains closely linked to the health situation in each region and to the effectiveness of economic policy measures. There are no simple answers: this is an environment that can lead to economic policy mistakes. The questions raised go far beyond the economic order alone. The new social and political issues are also challenges that need to be addressed. Interest rates are being kept artificially low in DE to protect the productive system and employment. Looking ahead, central banks’ policies will be decisive in anchoring inflation expectations. The private and public debt-to-GDP ratios have reached new records worldwide.

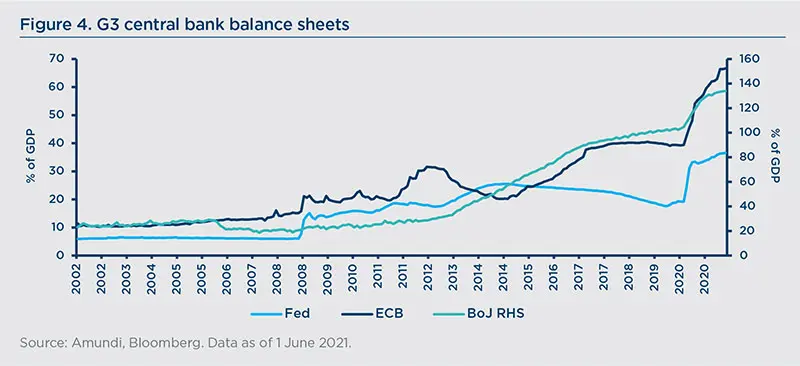

De facto, these debts have been partly monetised in the major advanced economies. The absence of inflation allowed CBs to pursue the same objective of economic stabilisation ‘hand in hand’ with governments. Looking ahead, conflicts between objectives may arise. While the duration and severity of the pandemic -- and the short-term economic trends -- are exogenous, the medium-term scenarios are to some extent endogenous, as they will depend on the behaviour of private (corporates and households) and public (governments and CBs) players following the crisis.

This is a period of multiple regime changes for which investors should be prepared. Under the new regime, inflation will be higher and real growth will be slower. This will challenge portfolio construction, as the traditional 60/40 approach should no longer deliver appealing risk/ adjusted returns in a world of lower expected returns for asset classes compared to the last decade. As such, the equity share of any balanced portfolio should be higher structurally, focusing on those stocks that could offer protection against rising inflation, a sort of real asset. There will be challenges also on the fixed income share: if inflation expectations are de-anchored, there might be rising pressure on bond yields and, consequently, investors should embrace a short-duration approach. Traditional fixed-income benchmark exposure, with high duration risk and low implicit yield, should leave the space for a flexible allocation across the full fixed income spectrum.

Here, we consider three possible dimensions of regime change: the first concerns the level of growth and inflation, the second concerns the volatility of the economic cycle, while the final one concerns economic policy, and more specifically the articulation between fiscal and monetary policy. These dimensions are interlinked with each other. The sequences are uncertain, particularly in the economic policy area. The monetary policy rules (e.g., Taylor rule), to which investors had become accustomed, have de facto disappeared from the radar screen. The Covid-19 crisis will give way to a more turbulent system, which is by its nature prone to policy mistakes and in which investor expectations may themselves be subject to jolts. These changes have deep consequences for investors’ asset allocation, which we attempt to summarise in the final section.

Regime shift #1: Stagflationary pressures likely to emerge

As the crisis ends, price pressures are likely to emerge (impact of stimulus programmes, pent-up demand, accommodative financial conditions), especially as supply constraints are likely to materialise at the same time (defaults/bankruptcies, disruptions in value chains, and bottlenecks). In addition to these cyclical pressures, more structural pressures may arise. The absence of structural reforms, rising inequality and climate change are generating political and social tensions, which lead to a medium-term rebalancing in favour of labour and a rise in input prices linked to the reshoring of value chains. In this scenario, the growth rebound would be short-lived: once the catch-up is over, GDP growth would return to its pre-crisis trend, or even lower in the event of capital destruction.

With productivity remaining unchanged, inflationary pressures could take root, with rising inequality, social demands and increases in social minima. In such an environment, central banks may have to raise rates to anchor inflation expectations. The subsequent rise in long-term interest rates would weigh heavily on indebted agents -- governments and corporates in particular -- and therefore on aggregate demand. This would result in financial turbulence; all the more so as risky assets are expensive by historical standards and have already priced in a recovery.

There is no real historical precedent for the current situation. The 1970s were marked by stagflation (recession/inflation), but in an environment that was very different from that of today. In particular, the global economy was largely dominated by the advanced economies, the industrial base was more than twice as large as it is today, and the degree of globalisation was less advanced. Moreover, the nature of the supply shock (oil price shocks) was very different. A reshoring of global value chains can lead to upward pressure on goods prices. However, it is unlikely that wages will soar as they did in the 1970s -- due to more flexible labour markets, a higher level of globalisation, lower rates of unionisation -- and that disinflationary pressures will disappear in services. Under these conditions, inflation could settle above CB targets -- say between 2% and 5% -- but not much higher. Rising indebtedness can drag down global demand. While inflation is welcome to facilitate deleveraging, it can also put CBs in difficulty, especially if inflation expectations are not well anchored.

Tightening monetary conditions too sharply (an increase in short- and long-term interest rates) would inevitably lead to a marked correction for risky assets, which appear quite expensive by usual metrics. Through the financial accelerator, a real or financial shock is propagated and amplified across the real economy as it leads to changes in access to finance.

Conclusion for investors: prepare for rising inflation and the fact that central banks may lose control of the yield curve.

Regime shift #2: End of the Great Moderation

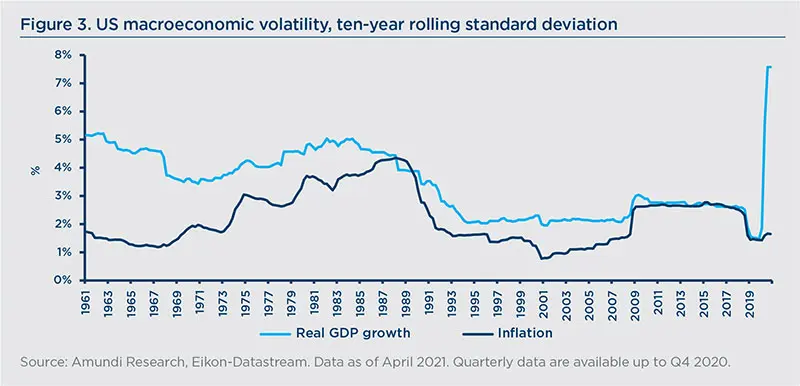

Since the mid-1980s, the volatility of output growth and inflation has declined to a post-war low in most OECD countries. A number of factors have been put forward to explain this period, known as the ‘great moderation’. First, many structural changes have taken place:

- Increasingly sophisticated computer technology has enabled companies to optimise inventory control.

- Development and deregulation of financial markets have made it easier for companies to finance their investments.

- In advanced countries, the transition from industrial to service economies has helped to smooth the business cycle.

- The growth of global trade and the free movement of capital have increased the flexibility of economies, making them more stable.

Second, progress has been made in terms of economic policy. In particular, central banks have gained greater independence, which has enabled them to fulfil their primary responsibility of ensuring price stability. Central banks have become more transparent in their operations and have improved their communication with the markets. The result of these developments has been a better anchoring of inflation expectations.

Finally, exogenous shocks have become rarer and less destabilising. In short, the decline in macroeconomic volatility is due to both ‘good policy’ and ‘good luck’. Surprisingly, the great financial crisis did not end the great moderation: for instance, in the United States, output volatility was never as low as in the ten years preceding the Covid-19 crisis.

Looking ahead, the notion of whether some of the factors that led to the great moderation will act in the opposite direction is open to question. The reshoring of certain value chains in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, the fragility of the service sector in the event of an epidemic, and the expected rise in inflation are all factors that are paving the way for bumpier cycles. This may lead to an unstable scenario of ‘fiscal dominance’, in which expansionist fiscal policies are combined with accommodative monetary policies to alleviate the debt burden. Such a situation would put central banks in a difficult position of having to contain inflationary pressures and maintain financial stability at the same time. At the end of the day, the ability of the policy mix to smooth out cyclical fluctuations as effectively as in the past is questionable.

Rising public debts and inflation could be an obstacle to stabilisation policies. Private and public debt levels have reached new heights with the Covid-19 crisis, surpassing previous peaks reached at the end of World War II (WWII). Looking ahead, rising debt levels are likely to dampen domestic demand. While inflation is welcome in facilitating deleveraging, it can also put central banks in trouble, especially if inflation expectations are not well anchored.

Debt accumulation is a game changer from a macro-financial standpoint. Tightening monetary conditions too sharply -- an increase in short- and long-term interest rates -- would inevitably lead to a marked correction for risky assets and trigger a ‘balance-sheet recession’. Not to mention the fact that economies may face more exogenous shocks in the future, such as epidemics, climate shocks, and conflicts. In a nutshell, both ‘good policies’ and ‘good luck’ may disappear at the same time.

The recent surge in output volatility has been accompanied by an equally large increase in earnings volatility, while inflation volatility has remained contained at this stage. Market volatility has been limited so far thanks to the ultra-expansionist policy mix and the absence of inflation. This may not last.

Conclusion for investors: bumpier business cycles would inevitably be accompanied by a resurgence of volatility in financial markets.

Regime shift #3: is MMT a regime shift for investors?

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) -- which is anything but modern -- has received a lot of attention in the past few years and even more so with the Covid-19 crisis. Questions about the limits of CBs' action (particularly the expansion limits of their balance sheets) are indeed back to the fore. These questions are highly controversial among economists: for some, this is a salutary paradigm shift, which will allow the true challenges (e.g., environment, inequalities, lack of investment) to be addressed. For others, CBs -- by deviating from their primary mission (price stability) -- are paving the way for the next financial crisis. If there is no inflation on goods and services, there is indeed inflation in real and financial asset prices. At the end of the day, bubbles are forming, threatening macro-financial stability in the medium term.

MMT advocates argue that the government could use fiscal policy to achieve full employment, creating new money to fund government spending. The MMT lies at the conjunction of two historical currents in economic research. On the one hand, a school of thought gives an important place to the over-indebtedness of companies and households in economic crises and shows the benefits of monetary creation by the state/CBs rather than by commercial banks. Contrary to what one might think at first glance, these theories were not developed initially by interventionist economists. On the contrary, they were developed by liberal economists such as Irving Fisher (“100% Money and the Public Debt”,1936), Henry Simons (“Rules versus authorities in Monetary Policy”, 1936), and Milton Friedman (“A monetary and fiscal framework for economic stability”, 1948) or by neo-Keynesians such as James Tobin or Hyman Minsky. On the other hand, there is the Keynesian school of thought, which emphasises the role of demand and the need to support economies through budget deficits to cope with recessions.

For MMT, contrary to Keynesian recommendations, monetary creation through budget deficits should not only take place to revive an economy threatened by recession, but to supply the economy with money permanently in line with the country's potential growth. It is therefore a real paradigm shift in economic policy that is not always well understood by the general public, or even by investors. Once an economy reaches full employment, the primary risk is inflation, which can be addressed by raising taxes and issuing bonds to reduce money.

Is Bidenomics the other name of MMT?

The U-turn in US economic policy following the election of Joe Biden has led to a debate on Bidenomics. For some, the new administration’s policy mix signals de facto an entry into a MMT regime. Investors often understand MMT as a blank check to spend more without worrying about debt accumulation. Simply put, MMT states that a country's debt is always sustainable when its government is able to print all the money it needs to refinance itself. There is nothing new or modern about this. As Alan Greenspan pointed out: "There's nothing to prevent the federal government from creating as much money as it wants and paying it to someone" 1 and "The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that. So there is zero probability of default” 2. As such, it is always possible, in a situation of underemployment, to implement massive fiscal stimulus plans financed by money creation. Under MMT, monetary policy is subordinated to fiscal policy (fiscal dominance) and the only limit to debt monetisation is inflation. While unlikely, when factors of production are underutilised, inflation becomes inevitable at full employment.

Despite appearances, there is a profound difference in nature between the QE policies conducted by central banks to finance stimulus packages and MMT. QE is a tool that is available to central banks to achieve their inflation target. QE certainly facilitates public deficits, but it is in theory limited in time and, above all, is supposed to be reversible. Central banks that conduct QE have not abandoned their mandate of price stability. On the other hand, MMT is presented as a paradigm shift. It is indeed up to fiscal (and tax) policy to anchor inflation expectations and redistribute wealth.

Tax is only a policy tool, not a means to raise revenue. Again, there is nothing new. In a famous analysis, New York Fed Chairman Beardsley Ruml had expressed the same kind of views at the end of WWII 3. “Federal taxes can be made to serve four principal purposes of a social and economic character. These purposes are: (i) as an instrument of fiscal policy to help stabilize the purchasing power of the dollar; (ii) to express public policy in the distribution of wealth and of income, as in the case of the progressive income and estate taxes; (iii) to express public policy in subsidizing or in penalizing various industries and economic groups; (iv) to isolate and assess directly the costs of certain national benefits, such as highways and social security.”

According to MMT, the lack of inflation over the past decades is the result of insufficient aggregate demand and it is up to fiscal policy to remedy this. On the contrary, inflation never comes from an excess of money supply but from an excess of aggregate demand. It is therefore up to fiscal policy, not monetary policy, to absorb it. Tax increases allow excess liquidity to be absorbed and redistribution to take place.

This theory faces many practical difficulties. Firstly, fiscal policy is not easily reversible. It is socially and politically much easier to pursue an expansionist fiscal policy (i.e., to generate inflation) than to tighten the screws. In the run-up to a general election, it is hard to imagine a government running a restrictive fiscal policy or raising taxes to slow down inflation. Secondly, fiscal measures take time (legislative time) and their effects on economic activity are by nature slower to materialise. Finally, moving from stimulus to austerity is difficult because of the very nature of fiscal commitments.

At this stage, Bidenomics cannot be assimilated with MMT. So far, low inflation and low interest rates have accompanied the monetary experiments of the last decade. By mobilising untapped productive resources, cyclical growth is likely to boost inflation. However, by promising to raise taxes -- on the wealthiest households, on corporations and/or on capital gains -- the Biden administration is not only seeking to finance its plans, but probably also to stem a possible rise in inflation and redistribute wealth in order to make growth more inclusive. Should Bidenomics fail to anchor inflation expectations, policy errors (like a premature monetary tightening) and greater macro volatility would be on the cards.

Implications for investors

Regime shifts will have deep implications for investors, in terms of changing risk premia and portfolio construction:

1.Investors should re-think the traditional 60-40 balanced portfolio.

This is a concept of the past and likely to die for many reasons. Firstly, expected returns for the next decade are lower today versus the previous decade.

For a balanced portfolio, the expected performance contribution from the fixed income component is limited and we cannot expect stellar performance from the equity component either. Over the past decade, equities have returned in excess of what was justified by earnings. As such, we can expect lower returns from the equity share of any investor portfolio. On the other hand, we see evolving correlation dynamics, with the bond-equity correlation turning positive amid rising inflation and higher volatility than its pre-crisis level. As such, the risk-adjusted profile of a traditional balanced portfolio is set to worsen. Therefore, investors should increase their structural equity exposure and build diversified portfolios, beyond the traditional benchmark allocation, including real, alternative and higher-yielding assets, such as EM bonds. As a result, portfolio construction will become more complex and investors will need to consider three dimensions: risk, return and liquidity.

2.Bond investing should go beyond benchmark.

Bonds are no longer the best diversifiers of global portfolios in a world of positive correlation amid higher inflation. In addition, bond investors are facing a benchmark duration problem: fixed income indices currently show extremely low yields, while their duration is at historical highs. As such, a small rise in yields could translate into large capital losses. Therefore, investors should move away from static, benchmark-constrained strategies and look for value in unconstrained strategies, to search for opportunities across the board. They should focus on all the income sources available across fixed income.

Core bonds are relevant for liquidity purposes only. Investors should embrace a short-duration stance with some flexibility. They should resist the temptation to go long duration too soon. For the coming years, the direction of rates is up. This will not be a linear path, but the trend is there. Against such a backdrop, investors should favour credit and short-duration assets (i.e., high-yield and EM short-term bonds).

3.In a world of lower returns, equities are a structural must-have.

Equity exposure is warranted against a backdrop of higher and more volatile inflation. It could offer protection against bubbles and market excesses (e.g., in the hyper-growth tech space). This means that investors should be cautious on interest-rate-sensitive stocks, while favouring dividend-yielding stocks and those exposed to real assets. The rotation from growth into value is a multi-year trend. Today, we are at an early stage, with higher inflation, commodity cycle and higher rates. These factors bode well for value stocks. To sum up, investors should hold more equities and factor in inflation risk. In addition, they should increase their equity diversification, with exposure to dividends, short-duration stocks and quality/value stocks.

4.Regarding ESG, in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis, governments have a strong focus on the fight against inequality (e.g., Biden’s American rescue Plan, Next Generation EU plan in Europe). As a consequence, the ‘S’ pillar is expected to gain prominence, thanks to new financial tools such as social bonds which are becoming a target of CB policy. On the ‘E’ pillar, the green transition is ongoing. New tools are being developed, such as temperature scores to measure the alignment of investment portfolios with the goal of net zero global emissions by 2050. Computing these scores across bond and equity indices, we find out that very few companies have a temperature score below 2°C, especially across EM. The climate transition will become more cogent over the next few years and many countries will have to adapt their development models. As such, there is scope for new asset classes, such as green bonds, to become a core component of any investor portfolio. The green bond market is growing fast and maturing, becoming more diversified. To sum up, ESG is a permanent trend that will require more discrimination among themes, sectors and stocks in the future. With ESG investing becoming increasingly relevant, it will be key for investors who look to generate excess returns to detect those opportunities where the ESG premium is not yet priced in fully.

________________________________

1. Declaration to the Committee on the Budget, House of Representatives, March 2005.

2. Interview on NBC, August 2011.

3. “Taxes for revenues are obsolete”, Beardsley Ruml (1945).