Summary

In the ongoing regime shift, investors have to deal with significant legacies stemming from the previous ‘Volckerian’ regime, namely two forms of inflation: asset price inflation over the course of three decades and, more recently, inflation in the price of goods and services. Underinvestment in the old economy fuelled, albeit with a lag, the return of good old inflation, while overinvestment in some areas of the socalled ‘new’ economy (the internet bubble in 1999, the tech hype between 2015 and 2021) financially inflated certain sectors.

These sharp discrepancies resulted from a combination of the demand for high returns on equity, which deterred real investment in most sectors, and the low cost of capital, which generated various forms of hubris, bubbles and leverage. Overinvested sectors in the ‘new economy’ may be a rising component of the landscape which lies ahead, yet some of these ‘tech dreams’ may be built on fragile ground. The fate of the broad economy lies, and will continue to lie, in the so-called ‘old economy’, as many people are beginning to understand the impact of scarcity in simple, immediate and vital things. The most obvious consequence is less growth and more inflation at trend: stagflation is the primary risk embedded in the new regime, just like deflation characterised the previous one.

In this new regime, something has got to give and it will, with profound consequences for investors. First among these is the realisation that the returns on equity (RoE) inherited from the previous regime are unsustainable. Investors must also bear in mind that it is highly uncertain whether inflated nominal economic variables will ‘bail out’ the current high asset prices. There will, however, be greater international diversification benefits to be reaped from the slowing global synchronisation of macroeconomic and monetary policy cycles. In general, investors should favour value stocks and sectors that are perhaps less glamorous but have more sustainable business models. Tensions are also likely to emerge in the forex space, wherein it will take some time for a new set of equilibria between major currencies to emerge.

How the shareholder regime brought about a major distortion

Overcapacity is over: there is scarcity all around

We believe that the current macroeconomic and financial environment is marked by the end of what we call the shareholder patrimonial macro-financial regime (or ‘shareholder regime’). This regime, which symbolically began with the arrival of Paul Volcker at the Fed’s helm, is now coming to a close. It generated major distortions and fragmentation in terms of investment and inflation, notably between the financial and the real spheres, as well as across sectors. In fact, the artificially low cost of capital – deriving primarily from monetary policies that were far too lax – has generated a huge ‘discount rate effect’ on the inter-temporal allocation of capital, described as an undue preference for certain goods and services and their related assets (the tech sector, but arguably housing as well) at the expense of others.

‘Easy’ money stimulated the financial sphere and asset prices first (i.e. accelerating the financial velocity of money or financial transactions per unit of money), before reaching the real sphere. Due to this lag, asset prices were strongly inflated, but a disinflationary pressure propagated in the real economy for some time. The low cost of capital further masked the shaky viability of business models in overinvested, future-oriented sectors, meaning that a recessionary pressure will manifest itself when excess capacities are unleashed down the road. Conversely, under-capacity in other sectors paved the way for supply-side problems and inflation. One aspect of the ongoing regime shift is that the mantra and narrative of ‘too much of everything’ (i.e. overcapacity) will likely be debunked. Scarcity is progressively being unveiled all around, not just in the energy sector; trapped in their comfort zones, few people saw it coming. Therefore, stagflation has its roots in the misallocation of capital, as well as ‘malinvestment’.

Misallocation of capital

The apparent fall in the cost of capital has not translated into higher investments: this is a distinguishing feature (and sweeping failure) of the current regime. The structure of allocation, and the distribution of cash flows back to shareholders, are key reasons for this misallocation. In fact, the focus on delivering high levels of RoE was accompanied by an implicit preference primarily for financial operations such as high dividend policies, share buy-back programmes and mergers & acquisitions (often financed with debt) at the expense of capital expenditure (capex).

Moreover, the discount rate effect stemming from low financing costs strongly influenced the net present value of assets’ future income streams. This further steered capital and cash flow away from generating new corporate assets – productive tangible assets in essential industries – and replacing old assets, towards existing ones. No naturally rebalancing forces were in place to counteract this one-sided channelling of capital. Notably, Tobin’s Q (the ratio of equity valuation versus the replacement value of real corporate assets, such that a high valuation should lead to a surge in physical corporate capital) did not mean revert.

Projects at corporate review committees often wound up being rejected. Despite an effectively low cost of capital on projects and the prospect of returns above this threshold, the projected cost of capital used in simulations proved to be much higher (up to 8%). While risk aversion may have played a part, much like it did in the vicinity of the 2008 crisis, it fails to explain in of itself this recent trend. The higher financing cost used in analysis may also reflect the perceived opportunity cost of conducting fewer financial operations that would be immediately profitable for shareholders.

Aggregate underinvestment did not exclude overinvestment and/or ‘malinvestment’ in certain areas, and bubbles formed on the back of promises for structural changes (the internet, tech, etc.). However, other vital and simple needs were simultaneously undergoing inadequate and insufficient investment. This shortcoming was suddenly exposed by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

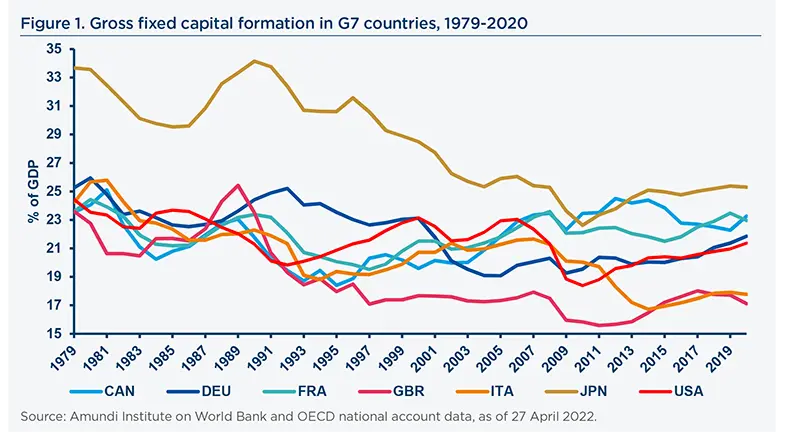

There have undoubtedly been sectoral disparities in the capital accumulation process. At the same time, there is no doubt about the big macroeconomic picture that is being painted. Fixed investment as a percentage of GDP has been trending downward in the West; while Covid accelerated this process, its seeds were sown long ago.

Capital, wages and the return on wealth: an unsustainable balance?

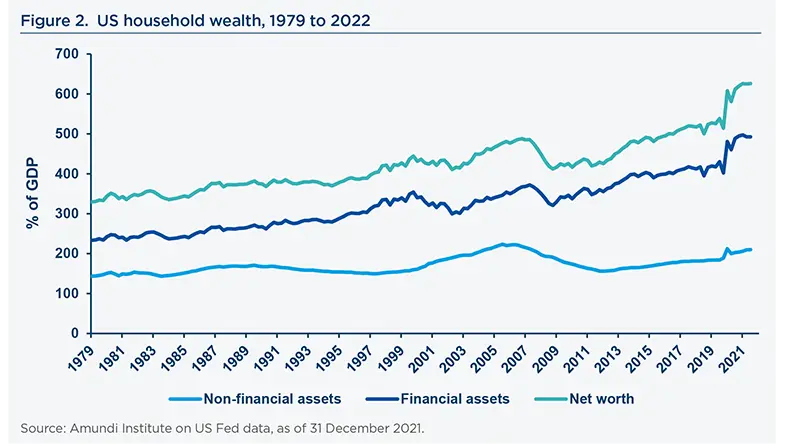

Another prominent feature of the shareholder regime was that wages were compressed together with capex. The decline in the labour share of income coincided with the rise of capital and this increase in the stock of wealth relative to income drove up the share of capital factor payments. The US is a notably emblematic example of this process.

The stock of wealth increased, with unchanged (relatively high) returns, as did the supply of financial capital due to the substitution between labour and capital. The falling reference interest rate and cost of capital played a key role in distorting the allocation between labour and capital as it did, within the capital space, between financial capital (‘wealth’) and productive, physical, tangible capital.

It is true that the real rate of return on total assets (the average of real returns on bonds, equities and housing, weighted by the size of each asset class) has been higher than the real GDP growth rate, not just in the past decade, but over a much longer period (1870-2015). However, within the shareholder regime that commenced in the 1980s, the stock of wealth has risen with no decrease in average returns: a fact that is consistent with a shift towards financial capital at the expense of physical, tangible capital.

Externalisation of capex and financing: the role of the Asian-Chinese platform

Within the shareholder regime, loose monetary policies and a high RoE system played a major part in the dual compression of wages and capex. However, the socalled ‘Chinese platform’ also contributed in the form of an external opportunity. In fact, part of the capex effort has been delocalised through extended global value chains, particularly in Asia (and notably China) where the cost of capital was even lower.

Devalued Asian currencies have been at the heart of this transition. The accumulation of foreign reserves, aimed at maintaining an artificial undervaluation of currencies to support an export-led model, was instrumental in depressing global risk-free rates through purchases of Western debt (particularly in the US, financing the current account deficit), even before Western central banks (CBs) initiated quantitative easing (QE).

In reality, the US had been exporting capital that exceeded domestic savings (current account deficit), which was therefore financed by recycled excess reserves from Asian CBs. This ‘chicken-and-egg’ game maintained monetary accommodation at both ends of the spectrum, fuelling various forms of credit and asset bubble booms and bursts. Savings have been confused with money and the so-called ‘savings glut’ was exaggerated and made instrumental.

Moreover, pursuing an objective of input accumulation (in the form of labour, capital and fixed investments) rather than an absolute increase in returns on capital, the Chinese platform further fuelled overcapacity and exported deflationary forces. In the West, this contributed to the reining in of productive capacity (since others were doing the job) and led to more CB accommodation and monetary complacency than was warranted. The powerful and disinflationary Chinese platform combined with the pursuit of demanding financial objectives in the shareholder regime, in a peculiar historical coincidence. As it were, the former allowed the financing of the latter.

Artificially low financing rates also misled observers into believing that r* (the non-observable neutral interest rate that neither accelerates nor slows down economic activity) was much lower than it was in reality. This found an expost justification in the exaggerated narrative of secular stagnation, rendered instrumental to identify excess savings (in fact, money) as an easy explanation for low rates. The West miscalculated the fact that what was seen as a permanent and structural feature of a globalised system – ensuring disinflation and a low cost of capital – was actually not.

Features of a regime shift unfolding: the end of a long but temporary exception

- As a new reality emerges from the Covid dust and the impact of cyclical fiscal stimuli wane, it will become apparent that the shareholder legacy implies both long lasting inflation and still-low potential growth. The present economic slowdown already reflects this message;

- Hopes to see a rapid fix of supply problems through an acceleration of investments are optimistic. It will take far more than is expected to change the approach and reasoning that are deeply embedded in the corporate culture of the previous regime;

- Something has got to give and it will. The incompatibility triangle (wages, capex and shareholder returns) in the context of inflation, higher rates and the need to expand real investments, cannot be managed at past levels of RoE. Public money will arguably do part of the trick through higher deficits and larger debt burdens. Nonetheless, something must also change on the private side of the equation;

- The Chinese platform will add to the dynamics of reversal by exerting less downward pressure on interest rates and inflation. The factors which supported the system are reversing one by one, through the gradual emancipation of the Chinese model, both in terms of the structure of GDP (a shift towards internal demand) and geopolitical aspects (tensions with the US). The system that is coming to a close implies embarrassing consequences for the West in terms of higher rates and inflation, changing CB policies in emerging economies with less accumulation (the looming geopolitical ‘weaponisation’ of FX reserves following the Russian crisis adds to this trend) and a shortening of value chains in relation to sovereignty and security issues;

- The energy transition will require investment that will not come from the Chinese platform. This transition is a macro-shock, whose intensity is comparable to that of the oil shock in the ‘70s, and implies an important reallocation of resources, employment, capital and massive fiscal transfers;

- The already optimistic demand for returns on equity inherited from this period have not been seriously revised and will soon face an even more difficult test, as will high valuations on risky assets in the context of rising rates (both nominal and real);

- The bottom line is that the regime of expected earnings must be revisited. The era of diminished financial returns, higher wages and rising cost of capital is about to commence, combined with a structural and massive need for higher capex;

- The dynamics of the previous regime made monetary policy a hostage to financial markets, for fear that a hawkish reversal would pressure asset prices, with negative macroeconomic spill overs. This contributed to the dynamics of the regime through a sort of reflexive feedback loop;

- Presently, monetary policy sits at the centre of tensions between alleged support for financial markets and inflationary benignneglect on the one hand, and powerful forces shifting towards more tangible capital on the other;

- The ongoing regime shift is unleashing fragmenting forces in the monetary policy space: there are, so to speak, as many reaction functions as there are countries facing inflation. This largely reflects the end of the ‘monetary consensus’ as a homogeneous set of principles (independent CBs, one tool, one objective-type models) and rules (e.g. the Taylor rule). The situation increasingly parted from a rule-based monetary system towards uncharted territories, pioneered by QE and various forms of debt monetisation, and a wider, undefined set of tools and objectives. The consensus has been shattered;

- During this monetary transition, some credibility will be lost and higher risk premia will be built. In the wait for monetary textbooks to be rewritten and a new consensus to emerge, investors find themselves in a transitory but dangerous wilderness;

- Nominal illusions can mask reality. The current regime shift is pushing the West to increase nominal variables (nominal GDP growth) through higher inflation, to alleviate the cost of debt. In this sense, there is a preference for inflation;

- In an inflationary regime, nominal variables such as growth, earnings and stock market revenues become unsurprisingly inflated, whether voluntarily (through financial repression forcing low nominal rates) or not. The juxtaposition between zero real GDP growth and nominal growth at 10% influences the way analysis should be run, certainly when looking at earnings, but also credit default rates: after all, corporates reimburse in nominal terms. There may even exist a hope that extreme valuations can be bailed out through sufficiently high inflation and nominal growth. This is an important dimension of the new regime for investors;

- However, while the possibility of a nominal illusion is an important dimension for investors, history calls for caution: all comparable periods have initially witnessed a downward adjustment in valuations.

Conclusion and implications for investors

Inflationary, structural supply constraints combined with asset price (inflation) bubbles threatening to burst and insufflate deflationary types of pressures, are the main legacy of the shareholder regime. This clearly points towards stagflation as an essential risk as we transition into a new world. Moreover, with fewer external sources of financial capital, pressure on Western domestic savings will increase and so will pressure on rates. The new, more inflationary regime characterised by diminished returns on the stock of wealth and higher returns on physical capital, will also be coupled with a rebalancing in the relative shares of capital and labour, in the latter’s favour.

For investors, the practical consequences are far-reaching:

- RoE objectives inherited from the previous regime are unsustainable. The incompatibility triangle (wages, capex, high RoE) in a world rapidly shifting towards higher inflation and financing costs, and the need to invest in the energy transition, imply a change in the earnings regime;

- If CBs do not prove to be serious about taming inflation, letting it run without hiking real rates to the necessary level, time will be bought for risky assets. However, this will not change the final outcome. Either natural bond buyers will be forced to absorb bonds despite the low real rates and hence sell risky assets, or eventually market forces will push rates ahead of the curve and hit valuations;

- Between the (a priori) deflationary bursting of a mature asset bubble and the unfolding – and then extension – of the inflationary cycle, it remains to be seen which will come first. A bursting asset bubble may stop and even reverse the real economy’s inflationary cycle, but the cycle can also extend the bubble. The most likely outcome may be that the inflationary cycle materialises together with the bursting of inflated asset prices, as the dynamics of inflation – which are deeply entrenched in supply side considerations – are unlikely to be derailed by the bursting of a bubble confined to a limited scope of the global economy. Overall, the main risk is a case of full-blown stagflation – recession and inflation. Investors should consider all three options in their portfolio construction, over a sequence of time;

- Global fragmentation will be accompanied by the return of international diversification benefits. The demise of the global monetary consensus, as well as its corollary: the retreat of the unifying factor of global trade and global integrated value chains, will diminish the co-movement of global risk and the correlation of country returns;

- From a sectoral perspective, investors should expect a change in the discount factor, itself driven by a change in how financial repression is conducted (from capping nominal rates at low inflation to capping real rates and letting inflation run higher). Whereas growth and technology stocks have been the undisputed winners of the previous regime, value stocks are the objective winners of the new one. Investors should pay closer attention to the sustainability of firms’ business models and look to less glamorous, but more realistic and effective, models compared to the technology stars.

- In the Forex space, we should not expect the return of the previous system of Asian CB reserves making up for insufficient US savings. Investors should brace themselves for many misalignments and tensions before a new, probably less USDcentric, order possibly emerges.