Summary

Natural gas prices have plunged since their summer peak, supported by ample stocks and by the EU emergency measures. While near-term stress has eased, longer-term supply/demand tightness remains, calling for higher risk premiums. As Russia loses its leverage, demand elasticity and weather might be the new pivotal gas drivers.

Near-term stress eased, longer-term supply/demand risks remain

Demand destruction, liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports and mild weather have helped restore EU inventories. Gas prices have plunged 70% from their summer peak, due to several factors:

- LNG imports have soared, especially from the United States, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

- Demand destruction in response to high prices has intensified, especially from industry, which makes up 40% of EU gas demand. Industrial gas consumption dropped by over 25%, especially in those sectors most sensitive to gas, such as metal fabrication, chemicals, food transformation, and machinery.

- China’s gas demand has slowed, due to the country’s disappointing economic performance, freeing up some volumes for Europe.

- Finally, mild weather in Europe, as well as encouraging November temperature forecasts, have helped reduce heating demand.

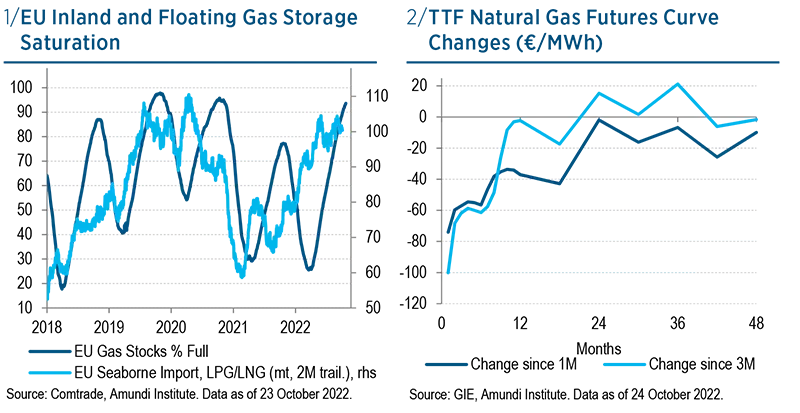

EU countries have now filled 93% of their aggregate storage capacities, a remarkable achievement considering the low starting level in spring 2022, at 26% vs. the seasonal average (35%).

A ballooning energy bill is helping bridge differences across EU countries

The EU is currently spending an extra €30-40bn per month on its energy bill, that is, an annualised 3% of GDP. That cost looks unsustainable but is helping to bridge EU differences. On 21 October, the EU crossed two of its red lines. Firstly, member-countries agreed on the principle of a ‘dynamic price corridor’ to cap gas prices. Germany overcame its reluctance; while being in a position to outbid other EU countries and having the financial reserves to mitigate the impact of skyrocketing energy bills through subsidies, Germany conceded some of its purchasing power and leeway.

Under this proposal, gas prices would trade in a flexible range, below what EU importers currently pay, but slightly above what overseas importers pay, to offer competitive premiums and reduce supply risks. It would apply across the EU to minimise internal competition. For such a mechanism to be effective, the EU would have to coordinate the distribution of gas across countries, a potential source of disputes. To such a respect, leveraging on the EU’s common purchasing power to buy gas could be part of the solution. Importantly, such a price cap should prevent fostering demand by offering consumers artificially lower prices.

The EU is also considering introducing a new gas benchmark, replacing the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF), designed to reflect the growing share of LNG in its imports. As Russian gas flows have dried out, Dutch LNG regasification has saturated, while available spare gas capacities have dwindled. As a result, TTF has decorrelated from other LNG indices and became highly volatile, making it costlier to hedge. As such, it has encouraged the search for alternative references. Yet, creating a liquid and reliable benchmark, both reflecting supply/demand dynamics and constrained EU gas infrastructure, will be challenging.

While aiming at reducing gas price levels and volatility, the price cap mechanism would need simultaneously to address supply security and the impact on demand. Common gas purchases and a new gas benchmark could help despite multiple challenges. The energy crisis might be a litmus test for European solidarity.

Refiled storage and EU solidarity efforts suggest hard rationing will not be necessary; however, there is no quick fix to replace lost Russian supply

Supply/demand dynamics under stress beyond winter

Fundamental gas drivers are likely to shift in 2023. Yet, with no quick fix to replace Russian volumes, stress would linger for longer. In 2023, LNG imports should rise modestly, by 5 billion cubic meters (bcm). This will not be a game changers. Higher relative EU price premium and new partnerships would make up for declining Norway output. However, LNG imports would be capped by the slow addition of regasification capacity.

Energy outages should also be milder next year. French nuclear reactors are expected to be online again by then, as well as the US Freeport unit, a key hub for LNG exports to the EU. Assuming the 2022 drought does not repeat, hydropower production could normalise. Yet, the ramp-up of other renewable energies is expected to take several years, starting with wind and then moving to solar production. Renewables could add 3 bcm in 2023.

These additions would be offset by an almost full shutdown of Russian flows. EU subsidies and price caps could also discourage energy savings and demand destruction. Demand from China would increase, reviving the EU-Asia competition for gas. Finally, we see no evidence that Dutch authorities are planning to revive the Groningen field, nor do we expect the EU to start pumping its wide underground shale reserves.

Overall, a modest rise in LNG imports and renewable production and fewer outage situations would be offset by a full cut of Russian flows and milder demand adjustment. This would leave the EU vulnerable to weather surprises and meaningful damages inflicted to its gas infrastructures.

Russia’s leverage on gas markets is declining. The relative supply inelasticity puts demand under the spotlight

Gas is now priced for perfection

Front-end futures are signalling lower near-term stress, not the end of the energy crisis. The drop in gas prices primarily results from higher-than expected EU gas stocks. Both inland and floating LNG storage are near full capacity, while LNG regasification units are saturated. As such, the EU is struggling to take on more volume, which has sent gas markets into deep contango, with the one-month contract trading above the one day forward. While front-end futures plunged, back-end futures barely moved, reflecting a still tense situation for winter. Gas prices might also reflect declining liquidity stress, thanks to measures to mitigate gas utilities’ margin calls and weaker capital base, including easier trading collateral requirements and several bailouts. Bid-ask spreads and price volatility have weakened accordingly.

The sharp drop in prices following the EU emergency measures suggests that markets have become convinced that necessity may force EU countries to overcome their differences. While we agree broadly, EU solidarity still has a long way to go and disagreement down the road could be a source of volatility.

At the same time, the EU vs. Asia gas price premium has vanished, suggesting a fading gas competition between these regions. Longer-term futures, as well as our expectation of higher Chinese gas demand next year tell yet a different story.

The relative cost of generating electricity still favours coal over gas despite the drop in gas prices. As such, power producers and industrial companies that can choose their energy source still have an incentive to favour coal over gas. Markets now expect coal to replace increasingly gas as the energy of last resort, hardly a signal that EU energy crisis is over.

Remaining Russian flows now account for a tiny fraction of EU supply. As such, Russia’s leverage on EU gas markets is fading. As a result, prices would become less sensitive to Russian manoeuvres, as suggests the fading correlation between TTF and assets sensitive to the Ukraine war.

After overshooting over summer, gas prices may now complacently factor in the vulnerability of EU energy markets

Demand is now the true variable

After overshooting over summer, gas prices may now complacently factor in the vulnerability of EU energy markets. Lost Russian volumes and the slow ramp-up of both gas infrastructures and renewable production would require demand contraction well beyond this winter, with limited room for surprises. Given the limited supply variability, demand would be the decisive factor in the gas equation.

The liquidity of gas markets and Russia are expected to have a declining influence on prices. More relevant price drivers for 2023 are likely to be the weather, inventory levels by spring, and demand elasticity . As a result, recession and rates prospects are expected to matter increasingly, too. We expect gas prices to rebound.

Meanwhile, energy inflation is expected to stay elevated. Along with higher rates, industrial demand destruction would hit manufacturing activity and add extra supply chain disruptions. While the EU is expected to try to better calibrate its subsidies, public deficits are still expected rise. In the longer run, lost Russian supply would prevent EU energy prices from reverting to the old price regime, eroding EU corporate competitiveness and leading some businesses to move their operations abroad, at least until renewables, greater storage and regasification capacities allow the EU to fill the gap.