Summary

Key takeaways

- Despite the growing economic and financial role played by women around the world, women are still heavily under-represented in positions of responsibility and on corporate governance bodies in 2024. In France, while representing 50% of the working population, women represent only 12% of CEOs across MSCI ACWI Index constituents. This figure is higher for a number of countries, including New Zealand (42.9%), Thailand (20.7%) and Norway (18.2%), yet lower in the US (8%) and Canada (3.5%), but the global average still remains below 7%.

- Gender diversity within companies is not just a matter of intrinsic value or a moral imperative, it is also a key determinant of economic growth: greater gender balance is associated with higher productivity, with an increase in competitiveness and with overall financial stability.

- Investors and asset managers have a key role to play to promote greater gender equality and diversity, and have several levers at their disposal to do so.

- First, financial instruments focusing on gender equality objectives are gaining traction: the gender-lens investing market is a rapidly growing segment of the sustainability investing universe and is attracting increasing investor attention. In particular, gender-focused sustainable bonds are useful instruments to finance projects to support gender equity, encompassing issues related to female empowerment advancement and equality.

- Engagement and voting powers are also important tools at the disposal of investors and asset managers, enabling them to better understand the challenges faced by companies and identify best practices to promote greater gender equality. For several years now, Amundi has been engaging with companies on the subjects of gender equality and the benefits of diversity, particularly within governance bodies. By 2023, Amundi had engaged with 482 companies on this subject.

- Despite the recent Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) backlash, especially in the United States, we believe that closing the gender gap is more important than ever: beyond the moral imperative it represents, it is also a key determinant of future economic prosperity.

Introduction: The economic rationale of gender equality

Over the last century, women have acquired the right to vote in almost every country, have entered the job market and political bodies, and have gained their independence, particularly financial. Equal rights have thus been achieved in society.

Still, one could wonder whether this equality of rights is sufficient to ensure equal opportunities, particularly within companies. The OECD’s 2023 Policy Insights publication, sponsored by Amundi, entitled Hard work, privilege or luck? Exploring people’s views of what matters most to get ahead in life, draws on survey data from 27 OECD countries. It finds that 53% of individuals surveyed believe that gender plays a role in social mobility, and therefore in hierarchical progression within a company. This perception is borne out by the figures: according to a study by the executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles, only 5% of Chief Executives worldwide are women. This figure is only slightly higher in the USA, with 6% female CEOs across the 500 companies in the Standard and Poor's financial index.

In France, in 2022, only 12% of CEOs of MSCI ACWI Index constituents were women. In other countries, the data is also telling: the share of women CEOs stands at 8% in the U.S., 3.6% in Germany, 1.1% in Japan, 6.3% in India, and 6.8% in China.1 While France’s figure is certainly better in comparative terms, it still shows that the country is far from achieving parity, even though women represent 50% of the working population.2

Gender diversity within companies is not just a matter of intrinsic value or a moral imperative. According to the OECD, gender diversity "enhances the growth, productivity, competitiveness and sustainability of economies”3 and could result in an average 9.2% increase in GDP in OECD countries by 2060, adding around 0.23 percentage points to average annual GDP growth. According to the IMF, these gains could be even larger in emerging markets and developing economies, where closing the gender gap could result in a 23% GDP rise on average.4

Indeed, gender gaps are indicators that productive human resources are under-employed or misallocated in an economy, thus having adverse impacts on productivity and growth. Reducing these gaps can lead to higher employment, a better match of skills with jobs, as well as an overall improvement in an economy’s stability, by increasing competitiveness and resilience to economic shocks.

Moreover, reaching gender equality in senior positions can be beneficial insofar as it “increases the diversity of thought and checks and balances”. For example, the IMF reports that a greater inclusion of women as users, providers, and regulators of financial services has resulted in improved stability in the banking system. Female representation in managerial positions and on corporate boards is also positively associated with an increase in firm performance (funding obtained, revenues, profitability…).5

As a result, it is clear that closing the gender gap can be a key determinant of future economic prosperity.

The market for gender-focused bonds: untapped opportunities for socially-minded investors

One way to tackle the issue of gender inequality is to invest in innovative financial instruments in the gender space. The gender-lens investing market is a growing segment of the sustainability investing universe and is attracting increasing investor attention. In particular, sustainable bonds focusing on women can be useful debt instruments to finance projects to support gender equity, encompassing issues related to female empowerment advancement and equality. The primary products of choice to tap into the gender-lens market are sustainability bonds, where issuers can combine environmental objectives with social objectives, and social bonds, where gender equity can be the sole focus of the bond. Finally, there is also a growing use of sustainability-linked bonds with gender equity KPIs.

According to Moody’s, of the sustainable debt issuances citing projects linked to SDGs since 2016, just over 1% of proceeds have been allocated to SDG 5 (“Gender Equality”). Despite this, the gender bond market has experienced a steady growth in the past 10 years, with cumulative issuance reaching $70bn between 2016 and 2021. In 2021 alone, proceeds from about $22 billion of GSSS bonds were earmarked, in whole or in part, for the financing of projects tied to SDG 5 for the achievement of gender equality and female empowerment.6

According to the Luxembourg Green Exchange (LGE), as of February 2023, there was a total of 169 outstanding gender-focused bonds: 145 in the form of use-of-proceeds bonds (green, social and sustainability bonds) and 24 in the form of sustainability-linked bonds.7 These instruments aim to positively contribute to women’s empowerment objectives, as outlined in SDG 5, while generating a financial return. Use-ofproceeds gender bonds must allocate at least part of the amount raised to SDG 5, while sustainability-linked bonds must have at least one Key Performance Indicator (KPI) and Sustainability Performance Target (SPT) aiming to reach gender equality or women empowerment objectives. The latter can include working towards ending all forms of discrimination against women or ensure women’s participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision making in political, economic and public life. Practically, for investors, this means investing in entities or projects that are owned or led by women, offer products and services for women, promote gender equity, and meet gender equality criteria.

European issuers are currently leading the way in the gender-focused bond market: when excluding supranational issuers, around 60% of gender-focused bonds and around 80% of the total amount raised by such bonds originate in Europe. Asia is the second most important region in the gender bond market, with 19 issuances ($1.81 bn), followed by North America with 13 issuances ($7.57 bn), South America with 9 issuances ($1.19 bn), and finally Africa with 5 issuances ($300 million).7

While gender bonds have been issued by all type of issuers, sovereigns, supranational and agencies (SSA) account for the large majority of issuances of these bonds – 66% as of February 2023 – with supranationals representing the largest component of the group. Financial institutions come second, with roughly 20% of total issuances, while corporates lag behind, representing only 14% of issuances.7

One of the reasons the gender-lens investing market has been limited to certain geographies and types of issuers appears to be the lack of clear guidance around issuance of and investment in gender-focused fixed income instruments. However, an increasing number of jurisdictions, especially in emerging markets, are expanding their taxonomies to include more principles regarding gender diversity: Mexico’s Taxonomy for instance has made gender equality a fundamental pillar of its framework, while Brazil’s Taxonomy also included social objectives in the newest version of its taxonomy.8

A good example of the uptake of gender-related bonds in Emerging Markets is the gender-focused social bond issued by Colombian bank Banco Davivienda’s in August 2020 for COP362.5 million (about $100 million). This bond was the first of its kind in South America, with clearly defined gender-equity objectives aligned with international standards. Proceeds from the bond are designated for loans to eligible women-led and women-owned small and medium enterprises in Colombia, as well as for social interest housing loans aimed at benefiting first-time female home buyers with low incomes.

Another area of improvement that is driving the growth of this market is the growing degree of disclosures on SDG 5 by issuers.9 This is especially important considering that, currently, most gender bond issuers disclose limited information on the allocation of their proceeds to gender-related projects.

As reported by the LGE, SDG 5 is often part of a wider pool of projects that include other SDGs and little information is effectively disclosed on the allocation of proceeds to gender-related projects. However, as outlined above, investors and global taxonomies are requiring increasingly more transparency and more granular disclosures. Recent publications by the International Capital Market Associations (ICMA) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC)10 are also helping the market move forward, by providing detailed guidelines for investors to evaluate new issuances and for issuers to be more aligned with investors’ demands.

Market initiatives, such as the 2X Challenge, can also help support investors to identify deals aligned with internationally-recognized gender criteria. Launched at the G7 summit in 2018, the 2X Challenge is a commitment by Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) to mobilize private sector investments in developing countries, focusing on women’s economic empowerment such as improved access to leadership opportunities, quality employment, and financing. Since its inception, the initiative has raised a total of $27.7 billion, benefiting 473 business across emerging markets11.

All in all, although the gender-lens investing market is still nascent, we believe there are a number of untapped opportunities in that space that socially- minded investors can take advantage of.

Engaging companies on gender equality: the role of investors

Another lever of action for investors to promote gender equality is through stewardship activities, including engagement and voting practices. For several years now, Amundi has been engaging with companies on the subjects of gender equality and the benefits of diversity, particularly within governance bodies. By 2023, Amundi had engaged with 482 companies on this subject12, i.e. 19% of the total number of companies engaged. This has enabled us to better understand the context, challenges faced by companies and identify best practices.

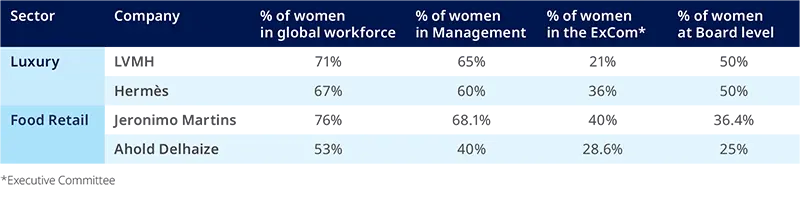

Unsurprisingly, we find a gendered distribution across sectors. The science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) sectors are heavily dominated by men, while women are working in the majority in services (healthcare, education, accommodation and catering, etc.). This difference has an impact on the financial resources of both genders, since the first sectors are the most lucrative from a remuneration standpoint, perpetuating the fact that capital is predominantly held by men. We also note that, even in highly lucrative sectors with a strong representation of women, governance bodies tend to be predominantly male. This is the case, at various levels, in the following two sectors that we view as particularly illustrative13:

In sectors with a high proportion of women in the workforce, the number of women tends to shrink with each new rank in the hierarchy. At LVMH, women represent almost two-thirds of the workforce, yet they account for just 14% of the Executive Committee members and 27% of designers within the Group.

However, since 2017 and the #Metoo wave, we have seen companies take this issue more seriously. The liberation of women's voices led to the departure of a number of male employees, including senior managers, as a result of inappropriate behavior towards women. For example, the former CEO of L Brands was removed from the company’s Board under shareholder pressure amid allegations of pervasive sexual harassment at the company’s subsidiary, Victoria’s Secret. These allegations also led to a shareholder lawsuit purporting that Board members concealed their knowledge of the misconduct.

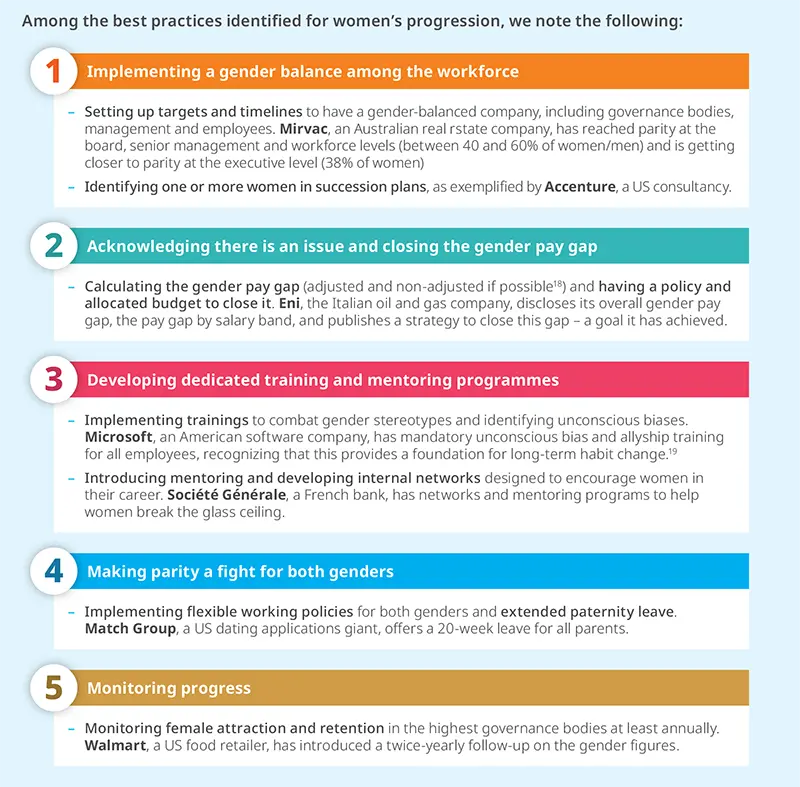

To account for these growing demands for equality, we have seen companies appoint Diversity Managers, often for the first time, and put in place Diversity, Equality and Inclusion (DEI) policies. Companies have also set quantitative targets for women’s representation, particularly in governance bodies. This trend has also been fueled by a growing body of legislation. In France, this began in 2011 with the obligation for large companies to have at least 40% of women on boards of directors. Ten years later, the Rixain law introduced a requirement for companies to have 30% women on executive committees by 202614 and 40% by 2029. Other European countries established similar rules, introducing a quota for women - or, more precisely, a quota for the under-represented sex - in their governance bodies, namely Germany, Austria, Belgium, Greece, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands and Portugal15. In Japan, since 2023, companies listed on the Prime Market have to appoint one female director by 2025 and reach at least 30% of women directors by 2030. In India, the 2013 Companies Act requires companies to have at least one female director. In the absence of legislation, companies face representation expectations in the form of soft law such as Governance Codes or equivalent – as is the case in Ireland, Israel, Poland, Sweden Turkey and the UK. This appears to have also contributed to progress: a number of companies in these countries have pledged to have at least 30% of women on their boards by 2025 or 2030.

Despite an initial outcry against the introduction of quotas for women in corporate governance bodies, regulations appear to have succeeded in shattering the glass ceiling: 10 years after the Coppé-Zimmerman law, France has gone from 10% in 2009 to over 45% women on CAC 40 and SBF 120 boards in 202016. In the UK, where gender diversity guidance is included in the Governance Code, women now hold 42% of board seats across large firms versus below 10% in 2018 - even though there were only 10 female CEOs amongst the FTSE 100 directors17. This suggests that soft law can also be effective at improving representation.

Our discussions with companies also enabled us to defuse a stereotype: the sectors where women are least present are not necessarily those where DEI policies are least developed. In fact, some companies have enacted solid policies and have seen a sharp increase in the number of women employed. For example, Legrand, a global specialist in electrical and digital building infrastructure company, aims to have 33% of women in the top 400 jobs by 2030. Over the last decade, the company has already managed to increase the share of women in leadership roles from 15% to 25%, which puts it on track to meet its target. This was possible thanks to several actions, including talent review sessions to increase the pipeline for recruitment and internal promotions, assigning sponsors within the company, and diligently monitoring compensation packages. The concerted effort, as well as the CEO’s commitment to reaching these goals, demonstrate an effective approach to advancing gender diversity within the organisation.

Diversity can be an important success factor for companies if managed well, and therefore it is one of the governance evaluation criteria in our voting policy. Amundi not only asks that governance bodies comply with the applicable laws in force, but also that companies be proactive on this issue, particularly in countries where there are no regulatory obligations. In developed markets, for example, Amundi requires each gender to represent at least 33% of the Board. In Japan, Amundi has just raised its threshold from one to two people representing the under-represented gender in the Board20. For other Asian and emerging markets, the Board of Directors must include at least one director of the under-represented gender.

Amundi has carried out a number of engagement initiatives around gender equality

In 2023, we engaged with 482 companies on gender diversity. These engagement efforts are bearing fruit: we have seen progress in companies' efforts around strategy development, adoption of quantitative targets and policies, and annual monitoring of key indicators.

Gender diversity engagement case studies

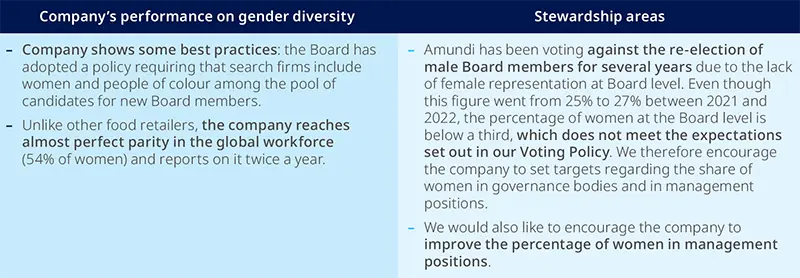

- US Food Retailer: Limited female representation in governance bodies, despite mostly female workforce and customers

The food retail sector employs a majority of women on a part-time basis, and its main customers are (still) women. Yet, they remain under-represented in companies’ governance bodies. Including more women in governance bodies would enable them to be more representative of the workforce and to potentially gain a better understanding of their target audience.

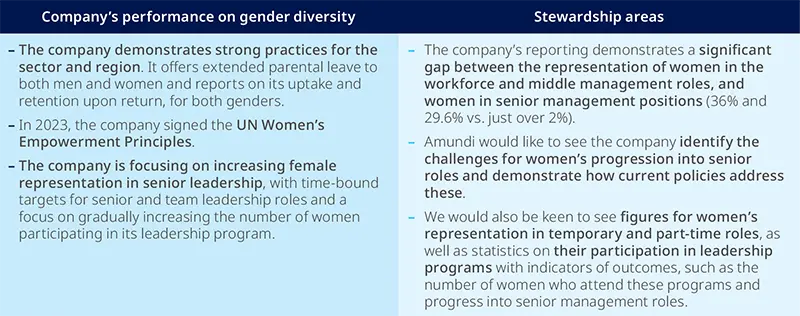

- Chinese Internet Technology company: attracting and retaining women is still a challenge

This company is a Chinese Internet and game services provider – for them, a diverse workplace can stimulate innovation and new ideas.

- South Korean Semiconductor Company: monitoring is key for anticipating and evaluating the success of gender diversity programs

Being able to attract and retain technical talent is critical to the semiconductor industry, where competition for skilled workers is intense. Women represent a still largely untapped talent pool, with their representation often hovering around 20% across companies, especially in technical roles.

Amundi’s position on DEI and Gender Diversity Engagement

Amundi believes in the value of promoting diversity, equity and inclusion as an integral part of responsible investing. We encourage companies to promote gender diversity on corporate boards, in senior management, and more broadly across the workforce.

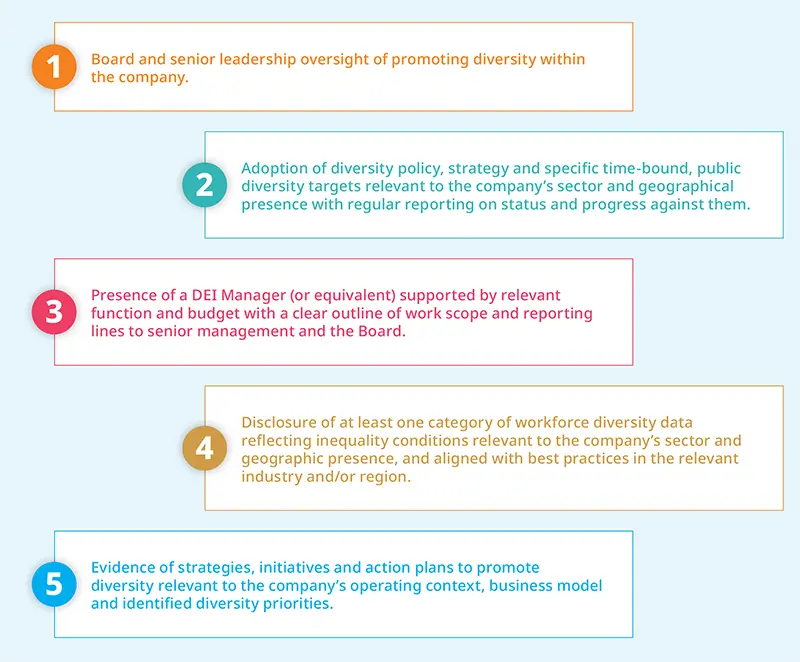

In our engagement with investee companies across various diversity themes, we seek to strengthen their strategy, management, and disclosure across several key categories of expectations, informed by research studies and global best practices23. These include:

Assessing the growing DEI backlash in the USA

While DEI engagements improvements are certain, they need to be sustained over the long term, in order to ultimately uproot the highly institutionalised psychological and cultural obstacles. Maintaining this effort over time will in fact be difficult, in a context where a counter-movement is arguing that DEI policies create discrimination.

This counter-movement won in a first phase when the US Supreme Court ruled that racially-conscious admissions programs at colleges were unconstitutional, in June 2023. Since then, several companies have been attacked due to their DEI policies. For example, Pfizer was sued by a membership organization, Do No Harm, as its DEI policy allegedly excluded white and Asian American applicants. The claim was ultimately considered invalid because the plaintiff was unable to identify a single person who was harmed by the company’s policy. However, the wave continued with other companies being attacked in the press and social media, and with boycott calls. That was the case with Disney when it publicly opposed a Republican law passed in Florida forbidding to discuss topics linked to gender identity or sexual orientation in a classroom. Target also faced backlash due to its 2023 LGBTQ Pride Month strategy, suffering substantial financial losses as a result. Its sales dropped by over 5% in the second quarter of 2023, partly due to the controversy, according to the company.

These notable cases were sufficient for many companies to review their DEI policies. Some even decided to step back entirely by erasing diversity criteria from executive bonus plans, such as tractor maker J. Deere, or to eliminate all diversity roles, such as U.S. retailer Tractor Supply.

This DEI backlash started in 2022 and strongly accelerated in the 2023 and 2024 voting seasons along with the anti-ESG resolutions increase in the USA24, a new trend that investors need to watch out for. Indeed, according to our voting data, the number of anti-ESG resolutions increased from 71 in 2023 to 82 in 2023 (+15% from year to year). At the same time, the number of anti-DEI resolutions rose from 1 in 2022 to 4 (x4) in 2023 and to 11 (x3) in 2024, showing that the anti-DEI movement is very recent and has increased rapidly. In 2024, anti-DEI resolutions represent half of the DEI resolutions in the USA. The percentage of these anti-DEI resolutions in the over-all anti-ESG resolutions has also increased: they represented only 6% in 2023 vs 13% in 2024. While we need to acknowledge this anti-DEI trend, it is important to note they are rarely supported by investors25. It remains to be seen whether the anti-DEI trend will hold and gain more support in the USA – and reach Europe or Japan.

There is, however, a positive side to the DEI backlash. Companies proclaiming DEI commitments with no true convictions will be led to drop the objectives they had no plans to reach. Meanwhile, those with a more mature approach to DEI will likely continue working towards their goals. Thus, vague commitments might disappear progressively, and the remaining targets will be more robust, quantified and results-oriented.

Ultimately, companies will need to go back to the roots of DEI policies: rather than being interpreted as a way to give opportunities to the less-represented gender solely because of its minority status, DEI policies should be seen as a way to give access to equal opportunities for all, no matter their gender or background. To address this backlash, companies will need to focus on demonstrating the positive impact that DEI policies can have for everyone and train employees to identify unconscious biases to resist them.

Conclusion: Taking advantage of the growing momentum on gender-smart investing

Despite a political and economic context favorable to the advancement of gender equality over the past century, women are still under-represented in positions of responsibility and on corporate governance bodies in 2024.

Investors have already used a number of tools to narrow this gap. The market for gender-smart financial instruments, such as gender bonds has grown significantly over the last decade. Active engagement with investee companies has also been a powerful tool for change. At Amundi, we have employed our engagement capabilities to encourage gender equality within companies, with concrete results. In 2023, we engaged with 482 companies on this topic to help them take steps to improve efficiency, encourage innovation and thus boost financial results.

We are convinced that diversity brings greater profitability thanks to a better understanding of customer expectations, higher operational performance due to the inclusion of a diversity of perspectives, and a greater capacity to innovate. However, we must also take into account a certain DEI fatigue and remind stakeholders that gender equality is not about promoting one gender over another, but rather about accessing a better talent pool by giving everyone the same opportunity set, regardless of gender.

For the gender investing landscape to truly grow and make a real difference in the life of women and girls, market actors will need to have a deeper understanding of what gender-smart investing means. We are confident that market guidance and initiatives will be key to accompany the growth of the market. In parallel, the availability of investment solutions will also need to expand in order to match investor demand and requirements, including in emerging markets and developing economies.

Sources and References

- https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/43943104/MSCI+Women+on+Boards+and+Beyond+2023+Progress+Report.pdf

- Part des femmes dans la population active dans l’Union européenne | Insee

- Executive summary | READ online (oecd-ilibrary.org)

- IMF, December 2023. Interim Guidance Note on mainstreaming gender at the IMF

- Ibid

- https://www.moodys.com/sites/products/ProductAttachments/Moodys_Breaking_The_Bias_Report_2022.pdf

- Luxembourg Green Exchange, Linking Gender and FInance: An overview of the gender-focused bond market, May 2023

- https://gsh.cib.natixis.com/our-center-of-expertise/articles/a-new-taxonomy-is-born-insights-on-the-mexican-sustainable-taxonomy

- https://www.sustainablefitch.com/corporate-finance/investor-questions-answered-2024-sustainable-finance-market-trends-21-02-2024

- https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/ICMAUN-WomenIFC-Bonds-to-Bridge-the-Gender-Gap-A-Practitioners-Guide-toUsing-Sustainable-Debt-for-Gender-Equality-November-2021.pdf

- https://www.2xchallenge.org

- Statistics taking into account the results for the « Social Cohesion – Gender Diversity » and « Strong governance for Sustainable Development – Board composition (Diversity) » categories.

- Data sourced from publicly available company reports, as of June, 30th 2024

- As of 2023, CAC 40 and SBF120 companies have about 25% of women at the ExCom, on average.

- Data sourced from ISS.

- Results disclosed by the French Haut Conseil à l’Egalité: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2 ahUKEwjN1pmFw-KEAxU6UqQEHR7dAAEQFnoECA4QAw&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.haut-conseil-egalite.gouv.fr%2FIMG%2Fpdf%2Flivret_-_10_ans_loi_ cope-zimmermann-2.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2YYkt6Xu6BFbipod5UPMdw&opi=89978449

- Women hold 42% of board seats at big UK firms, but just 10 are FTSE 100 bosses | Business | The Guardian

- The adjusted pay gap measures the difference in pay between men and women after accounting for factors determining pay, such as job role, education, experience. The non-adjusted pay gap measures the average difference in pay between men and women

- See 2023 Diversity and Inclusion Report.

- For companies with a market capitalization of less than $3 billion, Amundi requires that the Board of Directors include at least 1 person of the underrepresented gender

- The 30% Club is a business-led campaign to boost female representation at board and C-suite level in the world's largest companies. See https://30percentclub.org/

- The GEI index measures gender equality across five pillars, including leadership and talent pipeline, equal pay and gender pay parity, inclusive culture, anti-sexual harassment policies, and external brand.

- The Behavioural Insights Team (2021). How to improve gender equality in the workplace – evidence-based actions for employers. Available at: https://www.bi.team/publications/how-to-improve-gender-equality-in-the-workplace-evidence-based-actions-for-employers. - Dobbin, F., & Kalev, A. (2016). Why diversity programs fail. Harvard Business Review, 94(7), 14.- World Benchmarking Alliance (2021). Social Transformation Benchmark. Available at: https://www.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/socialtransformation-benchmark/

- The USA is the only country where we see anti-ESG resolutions

- The average support in 2023 and 2024 was about 2%, which is marginal