Summary

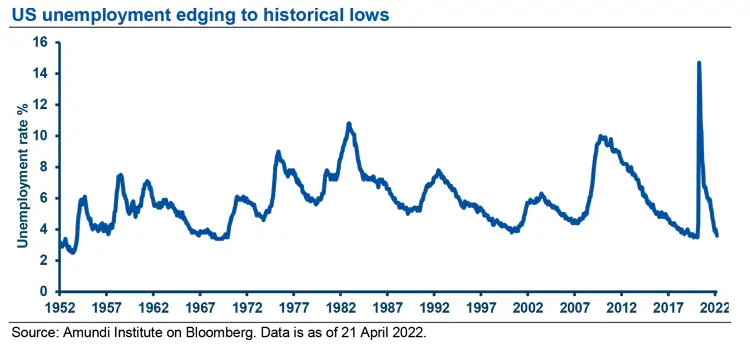

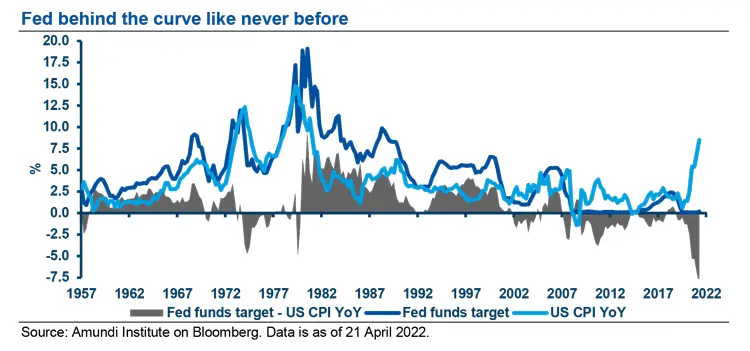

Over the past few months, price hikes above expectations have prompted cohorts of investors to proclaim, “the Fed is behind the curve!” It is a well-known fact that the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) statutory dual mandate is to target both price stability and maximum sustainable employment. On the second point, the US labour market has seldom been stronger. The latest projections place unemployment at 3% by the end of the year, an event that has not occurred since the 1950s and which should continue to foster economic growth. However, by any reasonable measure of inflation the Fed is in fact “behind the curve” on the first point. Inflation is running rampant, well above its 2% target according to the main measures (US CPI headline was at 8.5% YoY in March, while YoY core PCE deflator was 5.4% in February), suggesting the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) should be hiking rates more rapidly to suppress these price increases.

What does it mean that the Fed is “behind this curve"?

The latest projections place unemployment at 3% by the end of the year, an event that has not occurred since the 1950s and which should continue to foster economic growth.

Addressing this notion of being “behind the curve”, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard offers two interpretations. The first is rooted in a Taylor-type monetary policy rule whereby even by adopting generous parameter values – output at full potential, a -50 bp real interest rate and a 1.25% deviation of inflation from target – the rule prescribes a 3.5% policy rate. Given the Fed Fund range is currently 0.25-0.50 bp, this suggests the Fed is indeed behind the curve by approximately 300 points. The second interpretation is based on forward guidance. According to this view, markets have already moved ahead of the Fed’s effective action. As of 21 April 2022, the 2-year Treasury yield is 2.62%, which implies the Fed is still behind the curve (although relatively less than the Taylor rule suggests), and must hike rates in order to deliver on the forward guidance laid out since the final quarter of 2021.

What are the historical precedents?

Since the 1960s there have only been two other times when core PCE inflation was as high as today. The first was in 1974. Back then, the Fed downplayed the monetary factors that contribute to price increases. In light of its non-monetary narrative, it erred on the benignneglect side of policy: it kept its policy rate (and associated ex-post real rate) relatively low and fell behind the curve. Consequently, the real economy was volatile, inflation persisted and moved even higher, and multiple recessions ensued.

By 1983, the Fed had learned its lesson. It adopted a new approach to monetary policy and focused on the contribution of monetary factors to the inflationary spiral. This time it did not fall behind. The FOMC kept the policy rate high in the face of declining inflation, stabilising the economy until the 1990-1991 recession.

While the Taylor rule is an acceptable proxy for the terminal rate, arguably the Fed is behind by more than 300 bp given the leads and lags of policy transmission.

Where are we today?

My view is that we are closer today to the 1974 scenario. Not only is the initial “behind the curve” gap reminiscent of that in 1974, but also, despite its hawkish tone, the Fed’s narrative is once again built around non-monetary factors. Moreover, while the Taylor rule is an acceptable proxy for the terminal rate, arguably the Fed is behind by more than 300 bp given the leads and lags of policy transmission. The longer it delays taking action, the higher the terminal rate will need to be, due to the time dynamics of inflation. Nevertheless, the current monetary policy system is no longer rule-based. It is unlikely the Fed will increase rates to the level stipulated by the Taylor rule, but markets may very well bridge the gap and in doing so exceed the forward guidance.

It is also probably true that a genuine normalisation in the Taylor sense (or through markets endogenously exceeding the forward guidance) implies a high recessionary risk. The Fed is already too late behind the curve. While I agree with former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers’ assessment that policy normalisation is a catalyst for recession, I do not believe a full normalisation will occur. The Fed is caught in the crossfire between killing inflation with the risk of triggering a recession now, or buying more time for nominal growth to increase, with a potentially hefty price to be paid later on. It is likely (and human) that they will sway towards the latter. Insofar as simple neutrality will not suffice to stifle inflation, the Fed’s reasoning is even conservative. Action and an attitude that goes beyond neutrality is, strictly speaking, required.

A genuine normalisation in the Taylor sense (or through markets endogenously exceeding the forward guidance) implies a high recessionary risk.

Assuming neither a rapid Taylor-style normalisation nor market endogenous excess beyond forward guidance, what can we expect from a 1974-style scenario? Logically, there will be higher, persistent and self-perpetuating inflation. The ex-post real policy rate will remain relatively low for some time, but nominal rates will trend upwards, with no way to stabilise volatility in the real economy. The epilogue will be a recession which, while it can be delayed, cannot be avoided altogether. After all, “history does not repeat itself, but often it rhymes”.

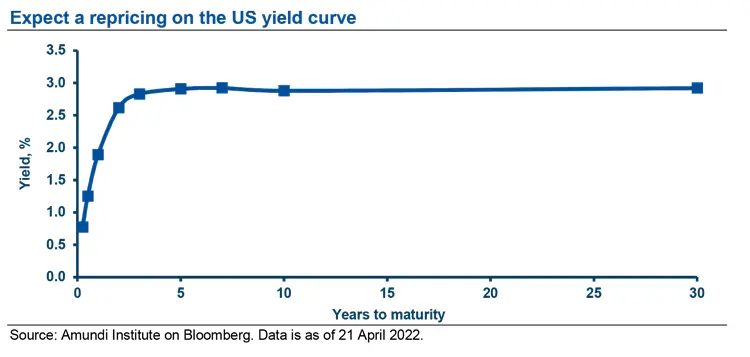

The final leg of this repricing will occur with additional pressure at the long end, via a steepening of the curve, signalling an inflection point for risky assets.

What are the investment implications?

Turning to the investment implications, there is an ongoing global repricing of risk underway. It started with bonds, particularly at the short end of the yield curve, but has since paused; this should remain paused or even retreat as the central bank delivers less than required, feared or priced into the market. The final leg of this repricing will occur with additional pressure at the long end, via a steepening of the curve, signalling an inflection point for risky assets and a preference for bonds. Large insurers and pension funds will play an important stabilising role in this respect.

In general, the performance of equities and bonds will deteriorate or even reverse course, provoking widespread underperformance. The repricing point in equities should see a tilt toward value and quality, which implies a positive outperformance for these sectors, while the lagging repricing of credit should catch up and could finally close the gap. Further repricing of equities and credit would provide a more comfortable signal that it is time to increase risk: that is, in order to consider adding more risk, we would want to see the 10-year portion of the curve plateau.

Definitions

- Basis points: One basis point is a unit of measure equal to one one-hundredth of one percentage point (0.01%).

- Curve flattening: A flattening yield curve may be a result of long-term interest rates falling more than short-term interest rates or shortterm rates increasing more than long-term rates.

- Curve steepening: A steepening yield curve may be a result of long-term interest rates rising more than short-term interest rates or shortterm rates dropping more than long-term rates.

- Quantitative easing (QE): QE is a monetary policy instrument used by central banks to stimulate the economy by buying financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions.