Summary

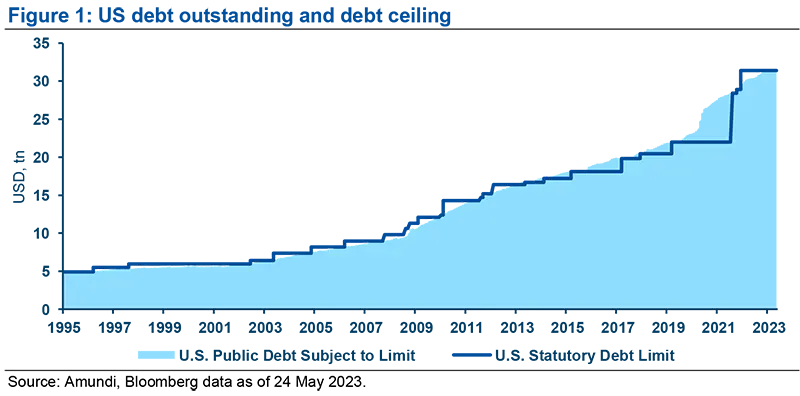

- What is it? US debt ceiling is a statutory limit imposed on the total debt the government is allowed to have.

- When is it due? The current debt ceiling was reached in January and the Treasury warned that it would run out of cash to meet its expenditure commitments around 1 June, although a precise date is impossible to predict.

- What is the most likely outcome? We think there is a good chance that an agreement to raise the ceiling is reached soon. The debt ceiling has been raised multiple times in the past, but requires approval of both chambers of the Congress. Hence, this time both political parties need to come to an agreement.

- What happens if an agreement is not reached by June 1st? In this case, the most likely outcome is that the government enters into debt prioritisation for a short period of time, paying debt servicing and debt principal payments before other expenditures.

- What would be the impact of debt prioritisation? Payments of salaries of government employees, health service, and social security payments could be partially suspended until an agreement is reached. Both sides of the political spectrum will risk losing support of the population, which will suffer a short-term liquidity problem through loss of regular income.

- What are the risks of a delayed agreement? A delayed agreement or a default (which we think is unlikely) might cause a credit rating downgrade, as was the case in 2011 (Fitch has just placed the US AAA rating on negative watch). In addition, a default would have terrible consequences for the markets: US Treasuries are considered to be the safest asset in the world, against which the pricing of all other financial assets (credit, equities etc.) is benchmarked.

- What could be the impact for the economy? The impact would depend on the nature of the agreement. The Republicans’ initial proposal asked for spending cuts to the tune of a 1-percent limit on the annual growth of nominal government expenditure over the next ten years. This fiscal contraction, along with a tight monetary stance, would be negative for economic growth. However, a default would be even worse for the economy.

1. What is the US debt limit or debt ceiling?

The US debt ceiling is the total debt the US government is allowed (as a statutory limit) to have/borrow. The current debt ceiling is $31.4tn and the government reached this limit in January this year. Since the US’ expenditure is bigger than the revenue it receives from taxes and other sources (as is the case for most governments), it needs to borrow money to meet its spending obligations such as social security payments, interest payments on loans, and so on. Hence, this limit is crucial to ensure that the government does not default on its commitments to holders of US debt. This limit can only be raised by Congress, and any change to the limit requires both chambers’ approval. Currently, the Republicans have the majority in the House of Representatives, therefore there is a need for Republicans and Democrats to reach an agreement to raise the limit.

2. When is the ‘X-date’?

The deadline for when the US Treasury runs out of funds to meet its expenditure commitments – the so-called ‘X-date’ – is 1 June, according to Treasury Secretary Yellen. Treasury cash balances depend on tax revenue, which is difficult to predict on a monthly basis. This means that the X-date could be slightly postponed, perhaps stretching to mid-June. Yet, we believe Secretary Yellen is being prudent given the uncertainty.

3. How close is Congress to reaching an agreement?

We see a high probability that an agreement is reached before the US Treasury will run out of funds.

Discussions on an agreement could be protracted. Both sides claim to be making some progress, but at this stage it is difficult to say how close they might be to reaching an agreement. Time is short, but based on past experience (the US debt ceiling has been lifted more than 70 times in the past 4 decades), we believe there is still a good chance for them to reach an agreement by the X-date (which, as we said, might move to after 1 June).

4. If an agreement is not reached, what are the other options on the table?

In the absence of an agreement, the US government has a few options to continue servicing its debt obligations. The main, and most likely option, is to prioritise debt servicing and debt principal obligations over other government payment obligations as they come due.

Some other possible options include:

- The President invoking the 14th Amendment (‘Public debt shall not be questioned’). However, we think this scenario is unlikely, because it would probably be challenged in the courts, and would further aggravate the political division between parties;

- The US government by-passing Congress and resorting to the Fed through measures such as minting a high-value platinum coin, or issuing perpetual debt (no principal obligations). We think this is also unlikely, because it could be challenged in Congress (which would see its purview over tax and spending decisions undermined), and it might also bring the Fed in the political arena.

5. What would be the consequence of ‘debt prioritisation’?

In case an agreement is not reached, the government will most likely prioritise debt payments, and a credit rating downgrade is also likely.

Prioritisation is more likely in the event an agreement is not reached by the X-date. The government will prioritise debt payments over other obligations, effectively using all tax revenues to meet debt payments first before other payments (i.e. government employee salaries, health service payments, social security, etc.) – until agreement is reached and the government can issue more debt. Based on past experience, we expect this period to be relatively short (a few weeks at most) because both sides of the political spectrum will risk losing support of the population, which will suffer a short-term liquidity problem through loss of regular income.

6. What are the risks of a delayed agreement?

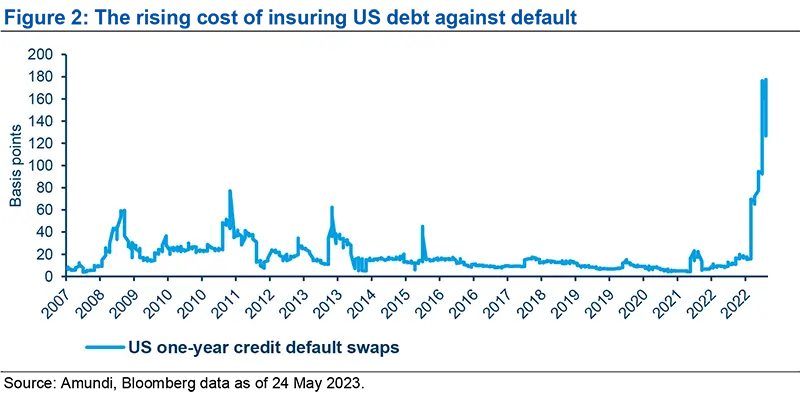

We don’t expect a default. Should this happen it would be catastrophic for financial markets and this explains why the cost of insuring against this event is on the rise.

A credit rating downgrade is the most likely scenario, as occurred twelve years ago. Fitch has just placed the US’ AAA credit rating on negative watch, in response to the current debt ceiling uncertainty. In 2011, S&P downgraded the US government a week after the agreement on the debt ceiling (August 2), and in the following month US equities declined by 15 percent. In the current negotiations, market volatility has been confined to short-term Treasury bills coming due for repayment, and the credit default swap market that is being used for hedging default risk. Yet, broader markets, including US equity markets, are not registering any material risk of a default or credit rating outcome.

We do not expect a US government default. Both political sides – Republicans and Democrats – have publicly stated that the US government will not default, indicating that they are aware of such an event’s significance for the US economy, as well as its importance for global markets. However, if the US were to default, it would have catastrophic consequences for financial markets because US Treasuries are considered to be the safest asset in the global financial system. Obviously, the cost of insuring against US debt default and interest rates in the economy, in general, would increase.

Yields on US Treasuries will rise, increasing the cost of holding other corporate debt (an increase in spreads), global debt, and equities. This is because the price of these financial assets is benchmarked to Treasury yields: any increase in the latter would affect pricing of these assets. Overall financial market volatility would remain high.

7. What would be the impact on the economic outlook?

A compromise leading to spending cuts at a time when monetary policy is also restrictive could further weaken the economic outlook.

This will depend on the nature of the agreement. The Republicans’ initial demands -- a 1-percent limit on the annual growth of nominal government expenditure over the next ten years is unlikely to materialise. But it is instructive. Any nominal limit on expenditure would effectively imply a fiscal contraction for every year where nominal GDP growth is above that limit. Such a restrictive fiscal stance combined with a restrictive monetary stance (broadly our expectation for the next few years), would result in a weaker economic outlook. A default could have far more severe economic consequences.

Source: CEA analysis, May 3rd 2023.