Summary

- The Net Zero landscape is changing rapidly due to changing regulatory frameworks as well as increased investor focus on climate scenarios.

- In this paper, we explore the main tools at the disposal of investors to embark on and navigate their Net Zero journey, looking at both opportunities and challenges ahead

- We first give an overview of Net Zero initiatives, that are raising standards and market practices by encouraging real-economy carbon reduction and increasing investments in climate solutions, as well as the remaining challenges

- We then analyze the importance of accompanying High Climate Impact Sectors in their decarbonization, focusing on the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for heavy industries in particular

- The third section looks at specific challenges for financing climate mitigation and adaptation in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDE), which account for two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions and are typically highly vulnerable to climate hazards. In this regard, blended finance partnerships hold significant potential to catalyze private capital towards the achievement of the Paris Agreement in EMDE.

- Finally, we explore the new frontiers of climate investing, focusing on circular economy and biodiversity investment solutions, both of which are essential to deliver on the Net Zero by 2050 objective.

Towards Net Zero alignment through market standards, initiatives and regulation

Net Zero initiatives are raising standards and market practices by putting investors at the forefront of the transition to Net Zero, encouraging both real-economy carbon reduction and increasing investments in climate solutions.

As the financial market and the real economy are two sides of the same coin, those believing that climate change has a material impact on the real economy should take a proactive stance in managing climate-related risk while developing a clear transition plan accounting for Net Zero objectives. In this regard, Net Zero initiatives are centralizing the best knowledge available in terms of principles, methodologies and tools for the financial sector to actively and effectively contribute to the Net Zero transition. Today, three target setting approaches are leading the way for investors : the Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance Target Setting Protocol (NZAOA TSP), the Net Zero Investment Framework (NZIF) and the Science Based Target Initiative (SBTi). All three converge on the below recommendation to effectively implement a Net Zero framework.

Net Zero needs to be achieved in the real economy, not just at the portfolio level

Decarbonising portfolios is one thing, decarbonising the real economy is another. As stated in the third edition of the NZAOA Target Setting Protocol, “The Alliance aims to avoid a situation where [the decoupling of the Alliance members’ targets from the real economy pathway] would require members to shift allocations from particular economic sectors to align their portfolios with the established target range. As investments are needed to catalyse the transition, this outcome would be highly harmful to the speed of the planetary transition to Net Zero as the real economy is left behind, hence limiting the real impact on global warming”1. In addition to taking capital away from the issuers that need it most, such a situation can raise fiduciary duty concerns, as investors would be ultimately forced to reduce their exposure to a significant part of the real economy.

Other than 2020, an exceptional year due to the Covid-19 pandemic where emissions decreased by approximately 7%, global energy-related CO2 emissions – including coal consumption – consistently rose over the past decades, reaching an all-time high in 20222 and is set to hit record levels this year. As a result, a “disorderly” transition, driven by disjointed policy actions, weighs more heavily on Amundi’s baseline scenario compared to a synchronized policy action scenario3. With the increasing risk of decoupling between Net Zero targets and the actual real economy pathway, asset owners should use Net Zero targets at Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA) level as a compass to navigate portfolios through the Net Zero journey, rather than a hard constraint. However, it is essential that Net Zero targets are complemented by a robust corporate governance and transparency framework with a clear transition plan for the short, medium and long term.

To contribute to the transition effort while effectively assessing climate related risk, members shall make the best use of the following two levers: engagement & capital allocation.

Engagement is the cornerstone of Net Zero initiatives

Engagement is seen as one of the most important mechanism financial actors have to contribute to a Net Zero transformation4. Engagement should be a holistic and purposedriven process with clear objectives focused on real economic outcomes, leading to a transformation of issuers’ business model and a so-called organic decarbonisation of portfolios. From ESG rating downgrades to potential divestment, consequences of inaction must be clear when Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are not reached in a predetermined timeframe.

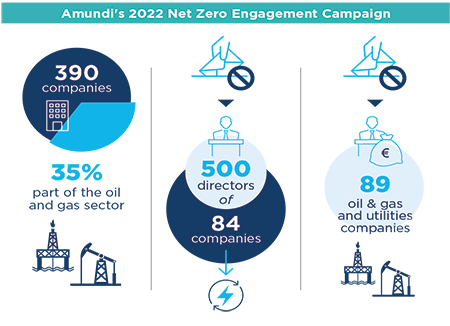

In 2022, Amundi launched a dedicated Net Zero engagement campaign to address both ambition and disclosure issues, with the aim to improve comparability and facilitate assessments against International Energy Agency (IEA) reference scenarios. We have provided companies with detailed recommendations on what we consider necessary to achieve Net Zero and what related disclosure Amundi expects5. Out of the 390 companies we engaged through this campaign in 2022, 35% were part of the oil and gas sector. In addition, Amundi expressed its concerns over the lack of climate ambition of the sector by opposing the re-election of more than 500 directors at 84 companies in the Energies & Utilities sectors and by voting against executive remuneration at 89 oil & gas and utilities companies.

Against a backdrop of war in Ukraine, inflationary pressures and desire for energy independence, some countries such as the United Kingdom and Norway are sending contradictory signals to investors by granting new oil and gas licences, despite the IEA's recommendation6. While the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) has issued a call to action7 to policymakers to bridge the gap between Net Zero commitments and action, we believe the need for coherent and comprehensive Net Zero campaigns to engage all stakeholders is more necessary than ever.

Allocate capital with a consistent climate-related risk framework and by gradually favoring best-in-class climate-aware issuers.

Assessing and managing a risk – such as that of climate – that has obvious pecuniary consequences for the real economy is sound risk management in line with fund managers’ and trustees’ fiduciary duty. Whether the transition is anticipated (“orderly”) or unanticipated (“disorderly”), we firmly believe that those who take a proactive stance by anticipating the risks and opportunities associated with climate change will be better equipped to face one of the greatest systemic challenges of our time.

$3.5 trillion of investment per year are needed between now and 2050 to achieve Net Zero targets, of which 70% should be dedicated to decarbonising the power sector. Of this share, over 70% needs to be mobilized by the private sector8. The need to align financial flows to companies and projects that are contributing to the transition is pressing. A diversified approach to climate-aware investing is crucial when implementing a Net Zero framework to effectively guide investments in the right direction. Limiting the analysis to a unique KPI (e.g. carbon emissions at the company level) can lead to inefficient conclusions, such as cutting investment from low and middle-income countries, and from high emitting sectors particularly in need of capital to switch their business model. As illustrated by Clarity AI9, sectors with the highest level of taxonomy alignment (by revenue) are respectively the utilities, real estate, industrials, material and energy sectors. Indeed, various combinations of climate KPIs at portfolio level, such as Implied Temperature Rise (ITR), avoided emissions or green share, can lead to different biases and outcomes, while all are contributing in one way or another to the overall decarbonisation goal at real economy level.

Moreover, according to the Climate Bond Initiative (CBI), energy, buildings, and transport remain the three largest use-of-proceeds categories for Green Bonds, collectively contributing to 77% of the total green debt volume as of end of 202210. Embarking High Climate Impact Sectors (so-called “HCIS”) is thus essential to efficiently contribute to the transition, as the greatest emissions reductions may be achieved by providing financing to issuers that are transitioning. That is the reason why Net Zero initiatives are recommending to adopt a sector-based approach while pursuing efforts to drive capital toward climate-positive solutions. Moreover, as no one-size-fits-all solution exists, financing strategies should be adapted to the specific features of the asset class, the geographical allocation and the investment style.

The case of climate benchmarks

From financed emissions reductions to favoring issuers with the highest incremental decarbonization potential.

In 2014, Amundi and MSCI designed a new series of innovative low-carbon indices on behalf of AP4 & FRR, with the aim of reducing the carbon footprint by at least 50% compared to the parent indices.

Five years later, the European Commission amended the EU Benchmarks Regulation to strengthen transparency and align portfolio trajectories with scientific evidence from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Paris Aligned Benchmarks (PAB) and Climate Transition Benchmarks (CTB) introduced new "transitional" attributes to capital allocation, notably by incorporating forward-looking indicators, minimum exposure to High Climate Impact Sectors, alongside a climate contribution aspect with the green/brown ratio. Since their introduction, financial products that are referencing a PAB or CTB benchmark have reached an estimated EUR 116 billion in 2023.

The democratization of PAB & CTB indices had a broad impact on both passive and active equity funds. Climate index methodologies – mostly equity – have been widely adapted to meet PAB / CTB requirements, while some asset owners with climate objectives have started to change their traditional benchmarks.

As a result, asset managers have started to develop climate index solutions, aligned with CTB and PAB requirements.

To date, we see a growing ambition gap between portfolio decarbonization objectives and the actual path of the real economy. This is pressuring carbon constraints strategies to reduce exposure to sectors (energy, utilities, materials, etc.) and geographical allocations (emerging markets) that are key for the transition. To overcome this challenge, new KPIs are needed to better capture the “organic” decarbonization potential of issuers (e.g. inclusion of carbon reduction targets, integration of sector-specific regional pathways, increased weight in climate solution, etc.) and a diversifying range of climate indices is welcome (CAC 40 SBTi, Carbon Budget indices, etc.). Supported by Finland’s largest private earnings-related pension insurance company, Ilmarinen, Amundi has worked with MSCI to develop climate solutions leveraging on metrics such as carbon intensity, Science Based Targets, climate risk management and revenues to assess, rank and select climate leaders. Active Managers are also leveraging on this trend by integrating sophisticated forward-looking metrics into the investment process (temperature scores, taxonomy alignment based on capex, etc.).

You can’t manage what you can’t measure: Climate data is central to keep track and demonstrate progress against Net Zero objectives

When it comes to the implementation phase of Net Zero, investors can feel overwhelmed by the wide diversity of climate metrics available. While ESG ratings are multidirectional and aggregated, there is a need to work with a higher level of granularity to assess the credibility of companies’ emission reduction targets. As a result, a wide range of climate-related metrics have emerged, from current metrics such as carbon emission intensity to forward-looking metrics to capture the transition potential of issuers.

At the Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA) level, carbon emissions measured in footprint or intensity are useful indicators to keep track of the overall portfolio Net Zero pathway. By using a top-down approach, investors can leverage on carbon attribution to better understand the drivers of the evolution of portfolio emissions11. Whether the evolution in carbon emissions is resulting from exposure to a specific asset class (absolute), from single issuers selection within an asset class (relative) or simply from capital reallocation, this can lead to a different interpretation of the evolution of financed emissions. In any case, carbon attribution should be used as a first step to inform about the evolution of the Net

Zero pathway, as carbon emissions data remain retrospective. Moreover, carbon emissions data have significant time lags, are usually estimated and are rarely sector specific.

To guide investment toward issuers and projects that are effectively contributing to the Net Zero objective, a more sophisticated approach is needed. Various taxonomies are being developed to identify business models that are already benefitting (revenue) to the low-carbon transition and companies that plan to transit toward such a business model (capex / opex). Yet, 60% of European companies do not have yet any revenue aligned with the EU taxonomy (50% for capex)12.

To accompany all sectors in their transition and reduce hard-to-abate emissions, forward-looking and sector-specific indicators are thus needed to estimate companies’ alignment and capacity to switch to a low-carbon business model (ITR, SBTi, Climate Transition Pathway, R&D investments, etc.). As unveiled in the NZAOA “Sector Call to Action” paper13, sector-specific data and disclosure remains insufficient for investors to adapt Net Zero investment strategies to sector specificities (carbon intensity based on physical output, energy efficiency / consumption metrics, etc.). Out of 44 NZAOA members, only 9 decided to publish sector targets14 - making this pillar by far the most neglected one. Yet, those data are crucial to compare companies on a like-for-like basis and allocate capital to best-in-class companies within sectors, rather than reallocating capital between sectors.

Stronger regulation and accounting standards are needed to improve transparency, coverage and quality of climate data

As illustrated above, climate metrics are empowering investors willing to navigate within the Net Zero journey and are paving the way for other environmental metrics. We see three catalysts that should enlarge coverage and enhance data quality overtime:

- The acceleration of Net Zero commitments at investor, company and state level.

- The ongoing updates in requirements of voluntary standards, accounting norms and Net Zero Initiatives (ISSB15, TCFD16, SBTi, ESRS17, etc.)

- And, most importantly regulation (SEC regulations18, CSRD from the EU19, etc.).

Despite the heated debate around the double materiality concept, one should welcome the upcoming international regulatory and accounting norms (ISSB and CSRD) that will gradually impose companies to conduct a materiality assessment, to publish short, medium and long-term transition plans, and to gradually disclose emissions across their overall value chain.

While implementing a Net Zero investment framework, investors should strive to adopt best practices. Whether for risk management, capital allocation, customer expectations or regulatory requirements, those who start first will be at an advantage. The more ESG data is used, assessed, compared and verified, the better it will be.

Importantly, to reach Net Zero by 2050, companies must tackle indirect Scope 3 emissions as it generally accounts for more than 70% of issuers’ carbon footprint. From an investor standpoint, Scope 1 and 2 emissions disclosure alone does not provide a complete picture of the carbon dependency of a company’s value chain. By nature, Scope 3 emissions mostly occur from sources owned or controlled by other entities, and thus represent direct emissions of other issuers. While the issue of double counting may be a limitation for accounting purposes, it should not prevent companies nor portfolios from reporting - and setting targets - covering full Scope 3 emissions. It is clear that it is in the interests of investors to have a complete and accurate picture of Scope 3 emissions, both for assessing exposure to transition risk and for setting and monitoring Net Zero targets.

Net Zero initiatives (GFANZ and IIGCC) and the EU Benchmark Regulation explicitly ask investors to report on carbon emissions while gradually phasing in material Scope 3 emissions. This leaves no choice for investors committed to the Net Zero objective than using data estimates, which in turn creates dependency on data providers and opacity in the carbon emissions data obtained. Data collection is key, and the complexity of calculating Scope 3 emissions presents significant uncertaincies. In addition, lack of supplier-specific data is still a challenge for most companies. Indeed, we continue to observe significant discrepancies on Scope 3 emissions between large data providers. With fifteen different Scope 3 upstream and downstream categories, poor data quality and inconsistency in Scope 3 reporting practices are thus major concerns. This leads to uncertainty and noise in the investment decision process that can be challenging to explain on an ex post basis. To date, Capegemini and CDP have revealed20 that while Scope 3 emisisons represent more than 90% of the emissions disclosed by European companies in 2022, only 37% are covered by current decarbonisation measures. Furthermore, only 8% of European companies have clear Net Zero targets for decarbonising their entire value chain by 2050.

More convergence across data providers and geographies is therefore needed to embed Scope 3 in both disclosure requirements and decarbonization targets. Despite imminent progress on this issue, we still see a divergence of approaches between jurisdictions, with Europe in particular defending the double materiality approach and the United States focusing on financial materiality.

In the EU, through CSRD, ESRS E121 outlines climate change mitigation and adaptation disclosure requirements, including GHG emissions from significant Scope 3 categories. This disclosure requirement should enter into force starting 2024 with gradual phase-in in line with CSRD implementation timeline.

In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) released in 2022 a proposal for climate-related disclosure in line with the ISSB and TCFD recommendation to disclose Scope 3 carbon emissions data if financially material or where a company has set Scope 3 reduction targets. While the approach is encouraging, the proposal faced major headwinds after a record 15,000 comments on the rule were sent from companies and investors. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is calling Scope 3 disclosure a “massively burdensome undertaking”. Still, California lawmakers recently approved a bill requiring companies with annual revenue in excess of $1 billion that operate in California to disclose their Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. At international standards level, the ISSB will require companies who are adopting the IFRS S1 (Sustainability) or S2 (Climate) standards, to disclose Scope 1 and 2 data early 2024, while granting an exemption for Scope 3 for a limited period of time (as short as 1 year).

Asset managers have a role to play in setting Net Zero reduction guidelines for asset owners

Asset managers can play an important role by developing guidelines to support institutional investors in reducing the carbon emissions associated with their investments.

We provide below the example of Amundi’s Net Zero framework, that is applied to our Net Zero Ambition strategies, across asset classes and geographies. This is, of course, one of the many frameworks available, and can be adapted to match investors’ Net Zero preferences or proprietary frameworks.

Amundi’s Net Zero framework

In line with Amundi’s commitment to contribute actively to global Net Zero objectives, we have announced our ambition to develop a “Net Zero Ambition” offering across different management styles, asset classes and regions.

With this objective in mind, we have developed a framework for Net Zero Ambition solutions, which defines the minimum standards for a product to qualify as such.

The Net Zero Ambition characteristics for our active product range are the following:

Investment guidelines

1. A global carbon intensity reduction objective to track progress at portfolio level. Amundi baseline:

- Achieve -30% in carbon intensity by 2025 vs. the carbon intensity of the benchmark in 2019 (base year)

- Achieve -60% in carbon intensity by 2030 vs. the carbon intensity of the benchmark in 2019 (base year)

2. A High Climate Impact Sector (HCIS) guideline to set a minimum exposure constraint compared to the investment universe. This ensures that Net Zero investors accompany the transition through the allocation of capital, and maintain their influence, through engagement and voting, on the sectors that are key for the transition to a low-carbon economy.

3. Exclusion of issuers whose business models are not compatible with the transition to a low-carbon economy: a Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) portfolio climate change mitigation objective

Issuer selection

Guide investments towards issuers fostering the Net Zero goal:

- Net Zero “Transitioners”: issuers that are gradually switching to a low-carbon business model :

- Issuers that show a positive momentum in terms of GHG emission reduction

- Issuers with credible Net Zero objectives aligned with their sector ambitions

- Issuers with a detailed plan to embark on a low-carbon trajectory

- Net Zero “Enablers”: issuers that currently have a low-carbon business model: Business model centered around green activities aligned with necessary ambitions

Engagement with issuers

Engage with issuers in order to enable the achievement of Net Zero goals:

- Target 1000 additional companies by 2025.

- Systematic engagement of investee companies exposed to thermal coal without a coal phase out policy.

- Dedicated Net Zero engagement campaign to address both ambition and disclosure issues

Accompanying High Climate Impact Sectors (HCIS) to finance the transition

Embarking High Impact Climate Sectors is a priority to accompany the biggest polluters and thus generate change in the real economy. Moreover, sector-based approaches and targets are key to achieve real GHG emission reductions, as they can incentivize capital allocation towards companies that are the best performers in their respective sectors.

In this section, we focus on one sector – heavy industries – which contributes to almost a fifth of global carbon emissons. In order to decarbonize heavy industries, the development of low-carbon technologies will be key. In particular, more private-public cooperation is key to reduce the cost of critical technologies (e.g. electrolyzers, batteries, solar, power…) required in a 1.5°C trajectory.

To tackle this need, the Breakthrough Agenda, first announced at COP26, is a commitment to work together this decade to accelerate innovation and deployment of clean technologies, making them accessible and affordable for all in this decade. Membership of the Breakthrough Agenda has now increased to 47 countries, now totalling over 80% of global GDP22 that have set sector-specific “Priority Actions” to decarbonize steel, power, and transportation.

In the box below, we deep-dive into current challenges for heavy industries in the context of the transition, focusing in particular on cement and steel that are part of the Breakthrough Agenda’s Priority actions, as well as on chemicals, which are also essential to the low-carbon transition’s success.

Achieving the low-carbon transition in heavy industries: the case of the cement, steel and chemicals industries

The massive carbon and energy footprint of heavy industries

The combustion of fuels and other process emissions occurring during the production of steel, cement, and chemicals have emitted more than 6.6 billion tons of direct CO2 emissions in 2021, close to 18% of global energy-related CO2 emissions.23

As these materials heavily support the global economy because of their specific properties and relative abundance, we will need them in the long term and their demand is expected to grow, even in climate mitigation scenarios aligned with a 1.5°C objective such as the IEA NZE.

These industries also represent a large share of the demand for fossil fuels. In 2019, steel represented 16% of the total coal demand and together with chemicals and cement it represented 24% of coal demand. Chemicals alone accounted for 8% of natural gas demand and 11% of oil demand, while together with steel and cement it represented 11% of natural gas and 12% of oil total demand. Reducing the reliance on these industries to fossil fuels is hence critical to lower demand for hydrocarbons at the pace required in the climate mitigation scenarios that are in line with the Paris Agreement.

Finally, heavy industries consume also large amounts of power (13% of total demand in 2019), this is expected to significantly increase with the uptake of electrified processes such as electric cement kilns, electric arc steel furnaces, and electrolytic hydrogen.

Responsible investors should hence push for ambitious climate targets in heavy industries.

Advancing the transition of heavy industries via our Net Zero engagement

In its Net Zero engagement campaign, Amundi strongly focuses on heavy industries. We ask steel, cement and chemicals companies to set targets in line with the Paris Agreement and report on a predetermined set of sector-specific indicators. In this context, we regularly refine an internal engagement framework that presents our recommendations and allows us to evaluate companies climate strategy in a standardized and consistent manner.

We present below a sample of key mitigation levers we expect companies from heavy industries to implement in order to achieve Net Zero emissions by 2050.

- Clinker (binding material in cement) is responsible for the vast majority of the 2.5Gt of direct CO2 emissions generated by the process of cement production.

- Fossil fuel combustion in clinker kils and other processes also contributes to greenhouse gas emissions.

- Steel production is responsible for 1.3 tons of CO2 emissions per ton of steel produced.

- Combustion of fossil fuels that provides the high temperature heat required during the virgin steel creation accounts for 90% of CO2 emissions.

- In particular, 75% of the final energy consumed by the steel sector is coal.

- Ammonia and methanol cause the majority of CO2 emissions released by the chemical sector.

- The majority comes from the production of hydrogen required in the composition of these chemicals.

- Substitute clinker for more sustainable materials such as limestone or calcined clay.

- Implement carbon capture systems to mitigate clinker’s impact.

- Replace fossil fuels for electrified processes or alternative low-carbon fuels such as renewable waste, biomass or hydrogen.

- Improve disclosure and set more ambitious targets on the percentage of clinker capacity equipped with CCUS24 systems and the annual amount of CO2 captured from CCUS.

- Increase the share of recycled steel, which releases near zero direct CO2 emissions.

- Phase out unabated coal during the production process by 2050 at the latest.

- Provide a plan specifying the modalities of exit for every coal asset owned.

- Develop carbon capture technologies to achieve 100% low-carbon steel production by 2050.

- Decarbonise ammonia and methanol production to remain within the global carbon budget.

- This implies a massive shift of the use of feedstock in the production of the required hydrogen, from the unabated use of natural gas or coal, to the use of power (i.e. electrolytic/green hydrogen) and the abated use (i.e. with carbon capture/blue) of fossil fuels.

While this sector approach is crucial to lead the most polluting industries to decarbonize, we also need to bear in mind regional discrepancies in the race to Net Zero. Indeed, emerging and developing economies face a number of challenges related to rapid urbanization and demographic growth, leading to rising energy demand and pollution levels. Additionally, the shift to a clean energy economy will require significant trade-offs for these countries, posing difficulties in particular for development models that are highly dependent on hydrocarbon revenues.25 To manage these trade-offs, governments will need to find development models that meet the aspirations of their citizens while avoiding the high-carbon path that other economies have pursued in the past. In the next section, we will deep dive into how emerging and developing economies can be accompanied in the decarbonization of their economies to contribute to the global Net Zero effort.

Accompanying the transition in Emerging Markets & Developing Economies (EMDE)

Accompanying Emerging Markets & Developing Economies (EMDE) in the transition towards Net Zero is crucial to reaching global decarbonization objectives. EMDE account for two-thirds of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while simultaneously being typically highly vulnerable to climate hazards26. In the past decade, EMDEs have accounted for nearly 95% of the increase in GHG emissions, and Net Zero alignment costs will be substantial as a result27. Within EMDE, Africa presents a major opportunity for blended finance to aid local decarbonization efforts, as recently outlined in a paper co-written by the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Amundi28.

Although progress has been made, the sustainable financing gap required to meet the Paris Agreement objectives in EMDE remains significant. On the one hand, yearly renewable energy financing needs in EMDE are expected to reach $1 trillion a year by 2030 if these markets are to stay on track to reach Net Zero greenhouse gas emissions by 205029. On the other hand, EMDE account for only one fifth of investment in clean energy, and annual investments in all parts of the energy sector have actually fallen by around 20% since 2016.30

In order to ensure that EMDEs receive climate mitigation financing, three major types of cross-border capital flows are available to deploy capital: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Foreign Portfolio Investment (FPI) and loans. Whereas FDI transactions are mostly dominated by large multinational corporations, financial actors are well-positioned to alter their portfolio flows. In order for financial investors to address the sustainable financing gap in EMDE, portfolio investments are key.

The role of blended finance

One of the ways international investors can help close the sustainable financing gap in EMDE is through blended finance, where development finance is strategically used to mobilize additional private finance towards sustainable development. Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) can provide de-risking mechanisms through a variety of financial structures (i.e. credit guarantees, tranching mechanisms, technical assistance etc.) aimed at enhancing the investability of projects for private sector investors. Blended finance structures can create win-win situations for both private and public sectors alike: while the private sector benefits from improved risk profiles, the public sector serves as an incubator to attract the required funding at scale. Blended finance initiatives such as Amundi’s Amundi Planet Emerging Green One (AP EGO) are key levers for investors to align their portfolios with the objectives outlined in the Paris Agreement while generating real-world additional impact. One way the fund generates significant additionality is through its Green Bond holdings, associated with projects that have been estimated to avoid 351,204 tCO2e, or equivalent to over 75,000 passenger cars being taken off the road for 1 year31.

Despite the potential for blended finance to mobilize sustainable capital at scale in EMDE, financial investor flows have not materialized accordingly. Governments, DFIs and MDBs continue to represent the bulk of transactions32, with private investors investors lagging behind. In contrast with the broader developments in global sustainable financing markets, commitments from commercial investors have meaningfully fallen in recent years, with allocated capital decreasing by nearly 80% in 2019-2021 compared with 2016-2019, partly due to a lack of strategic coordination and low levels of investor participation in Developed Markets (DM)33. While blended finance continues to be a well-recognized and widely used tool in the official development finance context, it has not yet gained similar popularity with private investors.

One way investors can increase their allocations to blended finance is through Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) centered around an investment fund as opposed to more traditional direct investments. Investing at a fund level can diversify risks across multiple projects and sectors while also attracting capital at a larger scale than direct PPPs. For reference, funds and facilities account for roughly half of blended finance deals in the last 10 years34. PPPs through funds can offer investors the opportunity to benefit from attractive risk/return profiles due to de-risking mechanisms offered by public finance and fund-level diversification while helping close the sustainable financing gap in EMDE.

Despite the limited historical private sector participation in blended finance, Amundi’s experience with its current blended finance partnerships is more encouraging considering the capital raised and investor types involved. From in-house experience through Amundi’s blended finance partnerships with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), there are clear signals that institutional investors are increasingly responding to fund-level PPP opportunities. Another example would be Amundi’s partnership with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which comprises a Climate Change Investment Framework (CCIF) to identify issuers that are integrating climate change considerations in a holistic manner. This framework is directly applied to an Asian climate bonds portfolio and has recently been implemented for other investors by a UK investment consultant. This testifies of the ability to apply this approach across different asset classes and geographies.

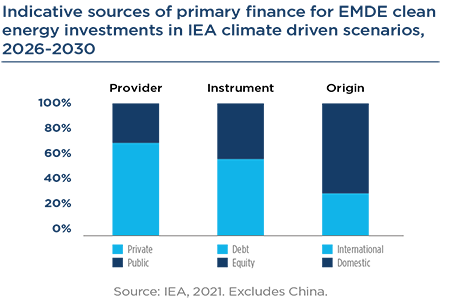

Energy Transition financing initiatives offer opportunities

As highlighted earlier, the world’s climate future increasingly hinges on decisions made surrounding the energy transition in EMDE. Today, these markets have relatively low per capita emissions and will require significant energy investments. Under the IEA’s climate driven scenarios, EMDE excluding China account for 40% of global energy investments while currently holding around 10% of global financial wealth35. The majority of required financing will have to come from international private investors through both debt and equity instruments, with the capital structure more likely to shift towards debt due to a shifting investment focus from fuels towards the electricity and end-use sectors.

Investors are in a position to take advantage of these significant financing needs while supporting the Net Zero trajectory in EMDE.

Case study: Slovakian Financial: Tatra Banka AS

One successful case study of fund-level EMDE sustainable finance can be found in Amundi’s AP EGO fund. As a lender, investor, asset manager, service provider and risk manager, the financial sector plays a major role in aligning the global economy with a net-zero pathway.

Tatra Banka is a leader in the corporate banking, private baking and premium segments in the Slovakian banking sector and is part of the Raiffeisen Bank International (RBI) Group. The sustainability strategy of RBI rests on 3 pillars: responsible banking, being a fair partner and active corporate citizen. Being a member of the group, Tatra Banka’s sustainability strategy reflects these pillars.

More specifically, the company aims to align with the group-level initiative of a 35% decrease in energy consumption from its operations and increasing the share of renewable energy in it’s energy mix to 35% by 2025. As a result, Green Bonds have become instrumental in achieving its sustainability goals. After developing a Green Bond Framework36, the firm issued a €300 million green bond in April 2021, aligning with the Green Bond Principles from the ICMA. In its effort to decarbonize operational activities, the company used the proceeds to invest in green buildings, renewable energy and clean transportation, with significant emissions reductions as a result. Since 2018, the firm has issued green bonds with a volume of roughly €1.8 billion, and the climate-friendly investments funded by the green bonds have resulted in annual savings of 77.100 tons of CO237.

Key initiatives in the context of EMDE energy transition

To accompany the mobilization of sustainable financing in EMDE, key initiatives aimed at scaling up private financing have already been launched at the global and regional levels. A sample of those can be found in the below table:

- Embodies the successful mobilization of private capital in EMDEs.

- Incentivizes coal-dependent emerging economies to transition away from fossil fuels to a Paris-aligned economy.

- Partner countries include South Africa, India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Senegal

- Set up by the European Commission to scale up sustainable finance and capital flows in low and middle-income countries.

- Focuses on identifying challenges and opportunities of sustainable finance and provide recommendations to the European Commission.

- Seeks to overcome obstacles such as identification of appropriate products, building a sufficient pipeline, and developing frameworks for the acceleration of capital flows.

- Set up by a coalition of international investors and co-chaired by Amundi.

- Striving to establish a comprehensive framework to assess sovereign bond issuers in the context of climate change.

- Aims to provide a publicly available tool to allow investors to engage with sovereign issuers while permitting governments to report on their progress in addressing climate change.

- Launched by the African Development Bank.

- Aims to help African financial institutions access global climate financing networks38.

- Enhances the raising and blending of capital from different sources e.g. domestic funds and concessional climate funds, to invest in green projects on the continent.

- Focuses on micro, small and medium enterprises which make up the most of the African economy.

- Supports the creation of new green banks to implement green financing instruments, facilitating transactions in local currency.

Conclusion: Exploring the new frontiers of climate finance to reach the Net Zero objective

Existing solutions offer a wide range of opportunities for investors to align their portfolios with a Net Zero emissions scenario while contributing to real-world emissions reduction. However, given the rapidly evolving ecosystem of climate finance, investors can look beyond more established climate investment solutions. To conclude this paper, we explore investment opportunities in the areas of circular economy and natural capital preservation, both of which are essential to deliver on the Net Zero by 2050 objective.

Circular economy as a tool to fight climate change

One of the ways through which investors can broaden the scope of their climate investments is through considering the circular economy in their asset allocation. Implementing Circular Economy principles can play a major role in achieving global climate objectives, by limiting the extraction of natural resources, reducing production thanks to the extension of the lifespan of products and allowing a better recycling of materials.

What do we mean by Circular Economy?

According to Ademe, the Circular Economy can be defined as “an economic system of exchange and production that, at all stages of the product life cycle (goods and services), aims to increase the efficiency of resource use and decrease the impact on the environment while developing the well-being of individuals.”

What can investors do?

The circular economy represents a multi-trillion-dollar economic opportunity, which investors can leverage on, as a means to deliver on the Net Zero objective. A study demonstrates that applying Circular Economy strategies in just five key areas – cement, aluminium, steel, plastics, and food – can eliminate more than 40% of the remaining emissions from the production of goods – 3.7 billions tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2050 – which equals to cutting current emissions from all transport to zero.

The circular economy has already started transforming entire sectors. For example, in the fashion industry, clothing resale is expected to be bigger than fast fashion by 2029. In plastics and consumer packaged goods, profit pools along the value chain are being transformed by rising regulation, public pressure, and innovation.39 Governments are accelerating this transformation. At the European level, the circular economy is a key pillar of the European Green Deal. At the country level, circular economy roadmaps and legislation have been implemented in certain countries, such as China, Chile, and France.

Investors can notably explore opportunities in three areas, that hold the most potential to reduce CO2 emissions, thanks to the good manufacturing of four key production materials – steel, aluminium, plastics and cement:

- Waste elimination can help reduce 0.9 bn tonnes of CO2 per year (-9.6%): this is possible through material efficient designs for buildings, industrialised construction processes and ligthweighting designs for vehicles. This allows to reduce the amount of material input in products and assets, and reduce waste generation during construction;

- Product reuse can help reduce 1.1 bn tonnes of CO2 per year (-12%): new business-models such as renting, sharing and pay-per-use can increase the use of products and extend the products’ longevity through reuse, refurbishment and remanufacturing. That way, the need for new products and end-of-life treatments decrease. The need for virgin materials, such as steel, plastics, cement and aluminium decrease as well so do the CO2 emissions;

- Materials recirculation can help reduce 1.7 bn tonnes of CO2 per year (-18%): new business models that consist in collecting, sorting and recycling activities help reduce the CO2 emissions as well. The increase of recycling rates allow to decrease the demand in virgin materials, which helps reducing emissions from production and end-of-life incineration by using less energy-intensigve facilities compared to the production of virgin materials.

Biodiversity acts as a natural carbon sink to limit global warming

Another approach investors can take to explore the new frontiers of environmental finance is through investments in natural capital. Preserving biodiversity and its ecosystems is essential to limit climate change. Indeed, terrestrial and marine ecosystems act as natural carbon sinks, absorbing around half of the greenhouse gases emitted40. As a result, preserving and restoring natural ecosystems is essential for limiting carbon emissions. In this sub-section, we will explore what approaches are available for investors that wish to invest with the preservation of biodiversity in mind.

What is biodiversity?

Biodiversity, which refers to all living organisms and ecosystems of which they are part, is also a key part declining at an alarming rate with now 1 million (out of an estimated 8 million) plant and animal species being threatened with extinction.

According to the IPBES 2019 report the main drivers of biodiversity loss are land degradation and habitat destruction; unsustainable resource exploitation; pollution; climate change; and invasive species. Human activities are both directly and indirectly driving biodiversity loss and yet nature provides economic and social value through material benefits (e.g. supply of food, water, fibers, wood and fuels) and other ecosystem services (e.g. climate and flood regulation, crop pollination, water and air purification, soil fertility, recreational activities, spiritual well-being, etc.).

What can investors do?

While the risks associated with biodiversity loss have always existed, global awareness of the subject is still in the early days. With regulations only beginning to emerge, investors have a key role to play. To limit biodiversity losses, a preliminary report by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) estimated that the global investment in biodiversity conservation required amounts closed to US$536 billion annually by 2050. Current annual global expenditures for biodiversity conservation fall heavily short of that, amounting to US$133 billion41.

At the moment, there are significant hurdles for investors to account effectively for biodiversity, including difficulties around data measurement and the need for clear global standards and guidelines. However, this complexity should not be an excuse for inaction. Work on the topic is moving fast: guidance notably provided by the Taskforce on Nature-related Disclosures (TNFD) gives companies a concrete framework to help them comply with new transparency requirements.

Moreover, engagement will continue to be a key tool for investors to push companies to adopt best practices and encourage standardized and transparent reporting on material ESG topics.

Amundi began engagement with companies on the topic of biodiversity in 2021, with the aim to advocate for best practice on biodiversity and ensure that companies are prepared to address biodiversity-related risks and impacts going forward.

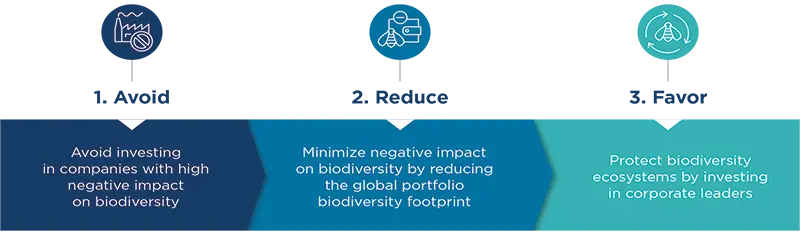

Beyond engagement efforts, Amundi has developed a framework to measure the impact of investment portfolios on biodiversity. With this framework, our ambition is to develop new thematic investment strategies focusing specifically on biodiversity matters.

Our approach relies on 3 pillars:

Sources:

1 https://www.unepfi.org/industries/target-setting-protocol-third-edition/

2 https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2022

3 https://research-center.amundi.com/article/rocky-net-zero-pathway

4 The engagement pillar is the only mandatory one of the NZAOA

5 https://about.amundi.com/files/nuxeo/dl/5994803c-6af1-4d7e-89e0-f1134f6374a7

6 https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/7ebafc81-74ed-412b-9c60-5cc32c8396e4/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector-SummaryforPolicyMakers_CORR.pdf

7 https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/63/2022/10/GFANZ-Call-to-Action-One-Year-On.pdf

8 World Energy Outlook 2022 (windows.net)

9 https://clarity.ai/research-and-insights/eu-taxonomy-reporting-first-look-at-the-2022-reported-alignment-of-400-european-companies/

10 https://www.climatebonds.net/market/data/

11 Carbon attribution models attribute changes in portfolio emissions to their primary drivers. This type of analysis uses methods drawn from performance attribution to understand the drivers of financial return in investment portfolios.

12 https://www.esgbook.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Challenging-road-ahead.pdf

13 https://www.unepfi.org/industries/urgent-call-to-companies-and-data-providers-for-critical-sector-data/

14 As of June 22, AOA Progress Report 2022

15 International Sustainability Standards Board

16 Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures

17 European Sustainability Reporting Standards

18 Securities and Exchange Commission

19 Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive

20 https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/007/198/original/CDP_Capgemini_report_July_13_From_Stroll_to_Sprint_-_A_race_against_time_for_corporate_decarbonization.pdf?1689231333

21 European sustainability reporting standard (ESRS) Environnement 1

22 https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/b551dc82-c4d3-4330-8975-2d3e07739a6f/THEBREAKTHROUGHAGENDAREPORT2023.pdf

23 IEA WEO 2022, Amundi ESG Research

24 CCUS: Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage

25 https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies/executive-summary

26 IMF, How Blended Finance Can Support Climate Transition in Emerging and Developing Economies, November 2022

27 World Economic Forum, 3 Actions to accelerate Emerging Market Climate Transition, 2022

28 AfDB and Amundi, Unlocking Climate Financing in Africa, 2023 https://research-center.amundi.com/article/esg-thema-13-time-action-unlocking-climate-finance-africa-0

29 IEA, Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging and Developing Economies, 2021

30 https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies/executive-summary

31 Data reflects annual GHG avoidance of all the green bonds in the portfolio with publicly available GHG impact data, including outstanding matured and sold bonds. For the six bonds sold or matured, the impact data has been prorated for the days of holding in 2022. Source: Amundi, AP EGO Impact Report, 2022

32 OECD, Scaling up Blended Finance in Developing Countries, 2022

33 Convergence, State of Blended Finance, 2022

34 OECD, Blended Finance Funds and Facilities, 2020

35 IEA, Financing Clean Energy Transitions in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies, 2021

36 Issuer’s Green Bond Framework, 2019

37 Issuer’s Green Bond Allocation and Impact Report, 2022

38 AfDB, African Development Bank launches model for deploying green financing across the continent, 2022 https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/african-development-bank-launches-model-deploying-green-financing-across-continent-56903#

39 Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019 https://emf.thirdlight.com/file/24/Om5sTEKOn0YUK.Om7xpOm-gdwc/Financing%20the%20circular%20economy%20-%20Capturing%20the%20opportunity.pdf

40 https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/five-ecosystems-where-nature-based-solutions-can-deliver-huge-benefits

41 The United Nations Environment Programme 2021, State of Finance for Nature