Summary

Summary

Profound changes in the international arena are underway. Together the EU, China and the United States are the three largest economies in the world. Whereas, previously, economic and geopolitical issues were treated separately, it is increasingly clear that the United States and China are using their economic power for geopolitical purposes. Such geopolitical leadership has economic implications.

In fact, the United States and China are the world’s only two superpowers. Accordingly, the US-China relationship is the most important bilateral relationship in the world. Almost all world balance depends on its development. The growing US-China rivalry will be the central geopolitical issue of the decade and a fierce competition between the two nations (across technology, standards and military power) is on the horizon. From an economic standpoint, both countries are seeking to increase their competitiveness in the ongoing digital revolution. From a geopolitical standpoint, both nations have natural allies either for geographical proximity or for historical reasons.

Europe cannot stay on the side-lines. However, the EU position is ambiguous, given its close economic ties with the emerging superpower and its historical and ideological relationship with the United States. The EU may play a decisive role in the new world order provided it strengthens and reforms itself to ensure its strategic autonomy. Neither the Unites States nor China will help Europe position itself in the new international order. Nevertheless, China -- and to a lesser extent the United States -- may ultimately be interested in seeing the emergence of a powerful and autonomous economic area in Europe that could act as a bridge, on certain issues, between the two superpowers. In any case, competition between these nations will be tough. The major blocks must agree on the ‘rules of the game’ to ensure long-term stability and peace.

Relations between nations evolve over the course of their history. This note aims to present, in a succinct manner, the stakes involved in the ambitions of the three great blocks that form the United States, China, and Europe. Their relationships will -- one way or another -- shape the world of tomorrow. This multipolar world is increasingly unpredictable and geopolitical tensions make it even more uncertain. Looking ahead, this could translate in unpredictable bouts of market volatility. The adage “do not put all your eggs in one basket” remains as relevant as ever. Just as it is dangerous to focus on one single asset class, it is also dangerous to focus on one region. The only free lunch in this new world is geographical diversification. The same is true for currencies. History teaches us that the dominant currency (or currencies) in the international monetary system is (are) the result of political, economic and financial power relations. Investors should remain vigilant on all these dimensions.

United States: How to maintain its dominance?

Main goal: secure its leadership on all dimensions (economic and geopolitical)

The Trump years have had a profound effect on international relations, particularly with respect to US relations with China and Europe. The arrival of Joe Biden as US President marks a turning point, but not a return to the Obama years. The Biden administration was quick to adopt a new position: noting that the world has changed; Secretary of State Anthony Blinken made it clear that US priorities could not be the same as in 2017 or 2009. The main priorities were stated, as follows:

- Revitalise ties with allies and partners;

- Tackle the climate crisis and drive a green energy revolution;

- Secure leadership in technology; and

- Manage its relationship with China.

The US-China relationship has been called “the biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century”. This relationship will be “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, and adversarial when it must be. The common denominator is the need to engage China from a position of strength.” (Blinken, 3 March 2021).

Trump’s unilateralism is over and Biden’s United States is based on a foundation of values and goals shared with European democracies, such as building a more inclusive economy, fighting global warming, consolidating democracies, and fighting racism and inequality. However the multilateralism advocated by Blinken is quite different from the one that Europeans may have in mind. The United States wants to reinvent partnerships with its ‘old allies’ – countries in Europe and Asia – as well as with its new partners “in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America”.

|

US-China rivalry: mind the geography and the economy Geography:

It is not only about physical geography. History matters: both superpowers see their ambitions as consistent with their own history, albeit with a different perspective. The United States wants to maintain its post-WWII dominance, while China wants to regain its lost power, with a desire for revenge on the humiliations suffered in the 19th century. America’s power is recent from China’s perspective. Economy:

1. Numerous partnership agreements: almost 20,000 joint ventures; and

China and the United States are interdependent: their economies are intertwined. China sees the United States both as a rival that it wants to supplant and as an indispensable partner for progress, particularly in new technologies and digital technology. |

|

US-China rivalry: two sources of dispute may poison the bilateral relationship On the economic front, it is all about trade On the geopolitical front, Taiwan and the situation in the South China Sea are the main sources of concern |

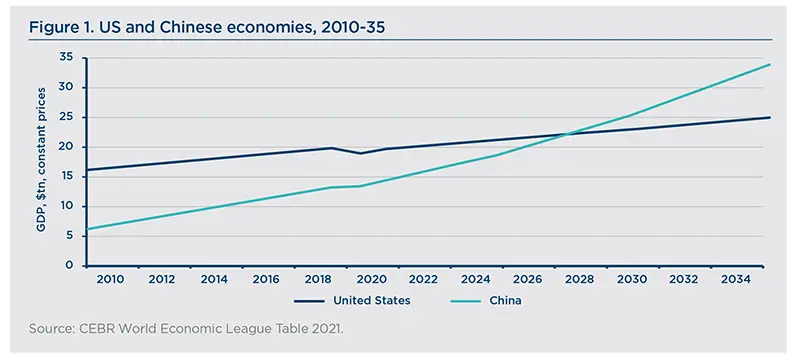

The Unites States is openly and increasingly concerned about the rise of China and its consequences. This obsession with China’s rise corresponds to a tangible reality: China’s real per-capita GDP is expected to double by 2035. China is making no secret of its technology ambitions, while the United States is seeking to maintain its dominance. Artificial intelligence and quantum computing are the two pillars of tomorrow’s technology, as identified by the new administration. The technological competition between the two blocks has only just begun. America will put all its energy into maintaining its economic dominance. The major stimulus plans announced by President Biden have both an internal and external purpose. Externally, the plans are designed to reposition the United States at the centre of the game, maintaining its leadership.

China: build a model increasingly centred on domestic demand

Main goal: build a new regional and global leadership, both economic and geopolitical

Beyond China’s growing economic power -- which is inevitable given its demographic importance -- it is its rivalry with the United States that draws the most attention. The economic aspect of this duel should not mask the multidimensional/global nature of the rivalry between the two nations. The US-China rivalry is on all levels: economic, technological, geostrategic and ideological. Some have argued that conflicts between China, an emerging superpower, and the United States, the current superpower, are inevitable. We believe this is a hasty judgment that does not take into account the high level of interdependence between the two nations. There is no easy win-win cooperation. However, a bilateral relationship is crucial to both sides. Both have an interest in finding common ground, if only because global stability is a prerequisite for achieving their own medium- and long-term goals, however divergent they might be.

This competition, which is not new, has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 crisis. China’s economic catch-up is accelerating and the two nations now need to find the right balance. Under President Trump, the relationship between the two countries had become more strained. However, such development is not only linked to Donald Trump. China sees the United States as both a rival and a partner. President Xi Jinping believes that a model combining progrowth policy and political authoritarianism is the most effective1.

China expects to play an increasingly central role in the new international order, in line with its economic rise. Some continuity (between Trump and Biden) in the strategic orientation of US policy is expected. But the experience of the last few years has shown Chinese leaders that they can no longer base their strategy on the expectation of a lasting, stable relationship with the United States. Sooner or later, the Democrats will give way to a Republican administration, which could again change direction. Against this backdrop, the Chinese strategy cannot be set in stone. That said, several major principles stand out:

- Focus on domestic priorities;

- Ensure that the external environment is not – and does not become – hostile;

- Reduce China’s dependence on the United States and, at the same time, increase the rest of the world’s dependence on China; and

- Increase China’s influence abroad (soft power)

Europe: caught in a vice between the United States and China

Main goal: EU to develop a new model based on strategic autonomy

The US-China rivalry should not obscure the strategic partnership between the EU and China: China is an important EU trading partner -- it accounts for 22.4% of all EU imports -- and an important partner on climate policy. At the same time, China is a systemic rival on issues of governance, values and multilateralism. The EU recognises and accepts this ambivalence, which “requires a flexible and pragmatic whole-of-EU approach”2.

It will be difficult for the EU to find the right balance between the United States -- a longstanding strategic and economic partner -- and China, its second largest market. Most EU countries see the United States as their main ally, especially militarily, and, at the same time, want to do more trade with China. On the one hand, China is seen as a key partner in addressing global challenges (e.g., climate change, WTO reform and Iran nuclear deal). On the other hand, Europeans are very concerned about several features of the Chinese model, which are incompatible with their own model for many and various reasons: a lack of fair competition, infringement of intellectual property rights, cyber-espionage, acquisition of European strategic technologies and infrastructure, and lack of respect for human rights (especially in Xinjiang). China is challenging hard these views voiced by Europe, evidencing the need for a close and constant dialogue.

These positions are difficult to reconcile, but one thing is certain: the EU needs its two main partners to maintain its prosperity. Europe is at a crossroads: to establish itself as a key player on an increasingly fragmented world stage, Europe must be prepared for difficult debates and negotiations, as tensions between the three blocks are inevitable. The main lines of action are beginning to emerge. The concepts of strategic autonomy and European sovereignty are increasingly emphasised. The EU wants to avoid a bipolar system, in which it would be forced to choose sides, at all costs. For instance, this is the reason why some EU member states refuse to ban Chinese companies from their 5G markets3.

For EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, the EU is ready to assume and strengthen its power. With this in mind, the EU has announced that it wants to double its semiconductor production by 2030 to 20% of world production. The Commission relies on several countries (e.g., France, Germany, and Spain) to strengthen the EU’s strategic autonomy and economic sovereignty, in particular its ability to develop key technologies independently of China, while managing its dependence on the United States. So far, the EU strategy has been to continue building the liberal system with like-minded countries (e.g., freetrade agreements with Canada, Japan, and Mercosur4), but also to harden itself in order to be able to compete digitally with the United States, China and Russia.

Strategic autonomy is a relatively flexible concept that refers to the ability of Europe to control strategic (i.e., potentially critical) technologies. This includes technologies that can have a significant impact on political institutions and values. Strategic autonomy can be defined as the minimum degree of control needed to maintain freedom of decision and action. It does not necessarily imply reproducing and developing an entire industry for each of these technologies. For the EU to play an active role in shaping a new international order, it needs to undertake reforms both internally and on the world stage, in coordination with other partners, such as recasting the WTO and redefining its foreign policy and economic policy (e.g., industrial policy, strategic autonomy).

Europe has assets and real potential in several strategic technologies (e.g., R&D, quantum computing, green energy, 5G, robotics, space). However, Europe remains very dependent on the United States and increasingly on China (data centres, cloud computing, information and communication platforms, supercomputers, artificial intelligence, undersea cables). Now Europe needs a significant political impetus in terms of technology policy. The lack of cohesion and cooperation between EU members is hampering action. European-based advanced technologies cannot be developed without the single market. And the EU strategic autonomy cannot be achieved without strong capabilities in advanced technologies.

Moreover, Europe must defend its model of responsible capitalism. Long-term social and environmental issues are at the heart of this model. To do this, Europe must address the issue of financial and accounting standards as soon as possible. It is clear that US companies currently dominate the market for nonfinancial data and ratings. The development of a ‘green taxonomy’ is a crucial issue for European companies. Europe also needs to assert itself quickly on the performance criteria used in ESG investments, in particular to highlight the social and governance criteria that are at the heart of its development model. These issues are deeply political and the EU will not be able to avoid power struggles, particularly with the United States.

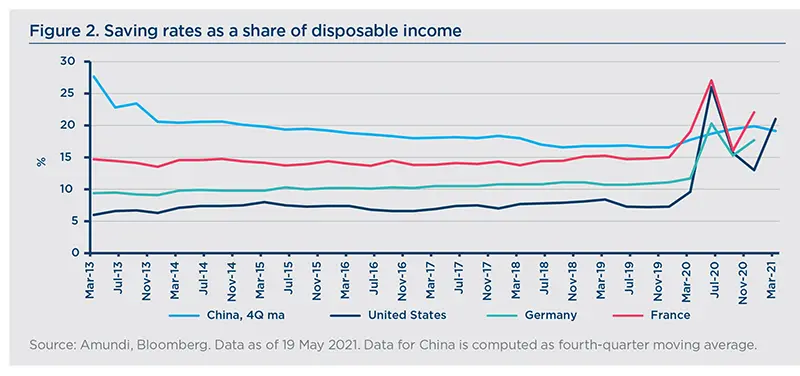

To promote its model, Europe has major assets, such as its very abundant savings. The Eurozone benefits from a recurrent currentaccount surplus. Provided it is channelled into regional investment projects, it is a strength. The Next Generation EU (NGEU) recovery fund will make it possible to deploy investments in key areas. Any delay in the start-up of the fund would have serious consequences. Cooperation, flexibility and speed of action will be the sine-qua-non condition for meeting the challenges. Time is of the essence.

|

EU-China CAI: a way towards European sovereignty On 30 December 2020, the EU and China concluded in principle the negotiations on the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). The agreement grants European investors greater access to the Chinese market and improves the level playing field for those already there. The CAI will provide increased legal certainty, improved market access and fairer engagement rules in this key global market for European companies, investors and service providers. In the agreement, China has committed to ensure fairer treatment for European companies, allowing them to compete on better conditions in China. These commitments cover stateowned enterprises, transparency of subsidies and rules against forced technology transfers. China also agreed to provisions on sustainable development, including commitments on climate and forced labour. The CAI commitments are enforceable (under a state-tostate dispute settlement mechanism) and subject to a monitoring mechanism seeking implementation of the commitments on the ground. From the Chinese side, this is the most ambitious agreement that China has ever concluded with a third country. It is seen as a turning point in EU-China relations, paving the way for further steps. Both sides agreed to continue separate negotiations on investment protection to be completed within two years of signing the agreement:

The conclusion of CAI after Biden’s election, but before he took office, is a good indication of what Europe means by strategic autonomy. The EU did not consult with the new US administration. The text of the agreement will now be legally reviewed and translated before it can be submitted by the Commission for adoption and ratification by the EU Council and the European Parliament. Source: European Commission, March 2021 |

|

China is among the EU’s largest trade partners China is a key trading partner for the EU, with a fast-growing domestic market of 1.4bn consumers. It is expected to contribute to almost 30% of global growth in the next five years. Over the past 20 years, European companies have invested €148bn in China. In 2020, China was the third largest partner -- the second non-European one -- for EU exports of goods (10.5%) and the largest partner for EU imports of goods (22.4%):

1. EU (€2,132bn, 15.4%);

1. Preceded by the United States (€2,293bn, 16.1%) and the EU (€1,940bn, 13.7%); and

1. Third largest partner for EU goods exports (10.5%), after the United States (18.3%) and the United Kingdom (14.4%); and |

A new world order, a new international monetary system

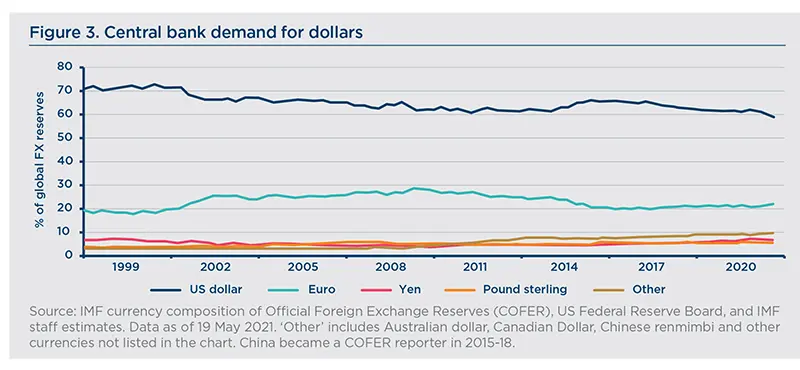

The 1944 Bretton Woods agreement established the dollar hegemony and allowed the United States to establish a Pax Americana. Since then, the dollar has dominated the international monetary system thanks to the preponderant role of the United States in the global economy. The US’s military power and technological lead have reinforced its position. Having a reserve currency has allowed the United States to finance itself easily and maintain its leadership, which has strengthened the dollar’s international role over time.

The Treasury market is now one of the deepest and most liquid in the world. As a result, no currency could replace the dollar in the short term. The dominant role of the dollar is often summarised by the famous words of John Connally, Richard Nixon’s Treasury secretary. In 1971, he said to European diplomats worried about the fluctuations of the dollar, “the dollar is our currency but it is your problem”. Now, half a century later, the dollar may start to become a problem for the United States.

Becoming a currency power is not only about being a dominant economic and trading power. The country that aspires to have a reserve currency must also offer a pool of assets denominated in its own currency. Above all, it must inspire confidence. Hard power is not enough. As former US secretary of State Joseph Nye theorised, real power comes from ‘smart power’, i.e., the ability to exercise both hard power (coercion) and soft power (influence and persuasion). Economic power is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition. As far as ‘soft power’ is concerned, the United States still seems to have the advantage. However, in economic terms, the increase in US federal debt and the expansion of the Fed balance sheet since the Great Financial Crisis and particularly since the Covid-19 crisis threaten the stability of the dollar in the medium and long term.

Central banks have begun to diversify their reserves: the dollar’s share of international forex reserves has been eroding since 2000, falling below 60% in 2020 for the first time since 1995 (59% in Q4 2020).

Two other currencies can claim the status of major reserve currencies: the renminbi and the euro. The euro is the world’s second largest reserve currency (21.2%), but far behind the dollar, while the renminbi still has a marginal role (2.3%). With the recovery fund in Europe (NGEU), we are witnessing the beginnings of Eurozone debt pooling, which should lead to a strengthening of its international role.

With the rise of China, particularly on economic, technological and military grounds, it is the future international role of the renminbi that is attracting most attention. The PBoC will be the first significant central bank to launch its digital currency (Digital Currency Electronic Payment, DCEP). The digital yuan is already being tested in several major Chinese cities and is expected to be launched on a large scale in 2022. The challenge for China is both economic and (geo) political. A digital currency would give some countries the opportunity to circumvent US sanctions by adopting the ‘digital yuan’, enabling China to develop its area of influence to the detriment of the US one. The yuan will see its weight in international trade and foreign exchange reserves increase.

Conclusion for investors: (geographic) diversification is the only free lunch

As of 31 March 2021, the US equity market accounted for around 41% of global market capitalisation, followed by the EU (10.3%5), China (10.5%), and Japan (6%). This structure corresponds more to yesterday’s world than to the world of tomorrow, even if we take into account the fact that companies have become very international. The centre of gravity of the global economy will continue to shift from Western to Asian economies.

The long-term benefits of diversification are no longer in question, this has been known to everyone since Markowitz’s work. However, today we live in a world with more asset classes and more interconnected markets. Strategic asset allocation requires a long-term view. Yet the world is increasingly unpredictable and geopolitical tensions -- which are inevitable in future -- make it even more uncertain. This will result in unpredictable bouts of market volatility. The adage “do not put all your eggs in one basket” remains more relevant than ever. Just as focusing on one asset class is dangerous, so is focusing on one region. The argument that foreign investment offers little or no diversification because of this increased interconnectedness does not stand up to long-term scrutiny. Even in times of market stress, when correlations between assets tend to increase, geographic diversification has its advantages.

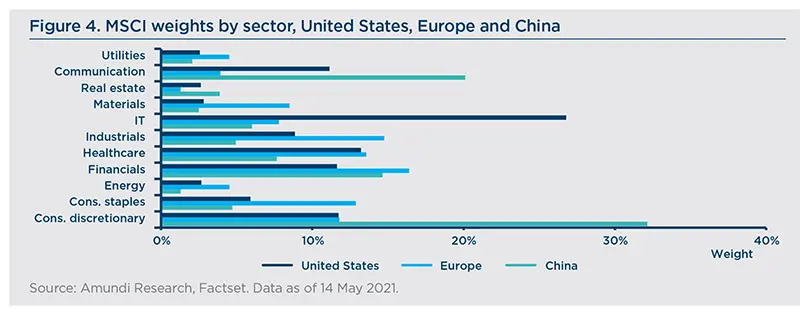

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, investors are often much more sensitive to geopolitical risks that are geographically close. Secondly, different countries are often orientated towards different sectors. The composition of emerging equity indices shows a clear increase in their exposure to domestic sectors over the last decade. Thirdly, the large advanced economies are seeking to re-shore part of their production in certain strategic sectors (e.g., technology and healthcare). In this context, future growth will be driven less by global trade and more by domestic demand. This should result in less correlated business cycles in the future. Finally, the emergence of new reserve currencies, in an increasingly multipolar world should provide new diversification opportunities. At the end of the day, it should be noted that geopolitical tensions can also have a direct economic impact through economic policies. For example, it is clear that the Biden administration’s stimulus packages are also aimed at maintaining US leadership. The resulting ultra-accommodative fiscal and monetary policies represent an additional medium- to long-term risk for investors.

As Harry Markowitz said, “diversification is the only free lunch” in investing. We strongly believe that what is true at an asset class level is truer than ever at a geographic level.

Definitions

1. The Covid-19 crisis is likely to have reinforced his position: less than 5,000 deaths were reported officially in China compared to 583,000 deaths in the United States and 832,000 in Europe (EU/EEA and United Kingdom). Thus a total of 1.4 million deaths have reported in the United States and Europe combined, with an overall population 40% smaller than that of China (number of victims is as of 13 May 2021).

2. “China is, simultaneously, in different policy areas, a cooperation partner, with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives, a negotiating partner, with whom the EU needs to find a balance of interests, an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance. This requires a flexible and pragmatic whole-of-EU approach enabling a principled defence of interests and values. The tools and modalities of EU engagement with China should also be differentiated depending on the issues and policies at stake. The EU should use linkages across different policy areas and sectors in order to exert more leverage in pursuit of its objectives”. European Commission, High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, EU-China: A Strategic Outlook, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, The European Council and the Council, Strasbourg, 12 March 2019.

3. Some countries want to portray themselves as a bridge between the United States and China.

4. Mercosur countries are: Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay. and Uruguay.

5. As percentage of the world market cap, European markets including Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Russia account for 16.5% and the Eurozone accounts for 8.1%. China, including Hong Kong, accounts for 16.4%.