Summary

The panacea of fiscal policy at no cost

The conversation regarding whether there is room for more aggressive fiscal policy is a hot political topic today. In the US, the debate is likely to become even more inflamed as we approach the midterm elections. In fact, these are at risk of becoming an evaluation of President Biden’s policies in light of the excessive fiscal spending carried out in response to the Covid pandemic (and its subsequent impact on the economy). On the one hand, fiscal expenditure has been identified as a leading cause of higher inflation. On the other, greater spending may be required should the US economy decelerate more than expected, particularly as voting day is rapidly approaching. Likewise in Europe, greater fiscal action is required to subsidise skyrocketing energy costs and to limit the economic impact of the Ukrainian conflict. At the same time, concerned voices are being raised as to whether harmonised Stability and Growth pact rules are still appropriate for the Union.

Additionally, gauging the scale and scope of the fiscal impetus implies revisiting the role of monetary policy as well. For several years, monetary policy has assumed a dominant role in the policy mix. It was widely regarded as a panacea to heal the wounds of the great financial crisis in a low growth, low inflation world. Little by little, the limitations of non-conventional policies are becoming apparent. Although low (and sometimes negative) interest rates have been a weak incentive for investments, the resources dispensed by policymakers have mainly been funnelled into financial markets rather than the real economy, generating a discrepancy between market prices and fundamental values. Consequently, the social inequality gap has also widened, albeit indirectly.

Nonetheless, starting with the Covid pandemic, and later accentuated by the conflict in Ukraine, fiscal policy has made a strong comeback on the policy mix stage. It has been called upon to support growth in a context framed by the energy crisis, through structural investments and reshoring in certain strategic sectors (such as healthcare and defence), where vulnerabilities (due to underinvestment) have been exposed by recent international developments. Over the long term, fiscal policy will also need to face the structural challenges that lay ahead, such as the green transition, which will require massive amounts of funding.

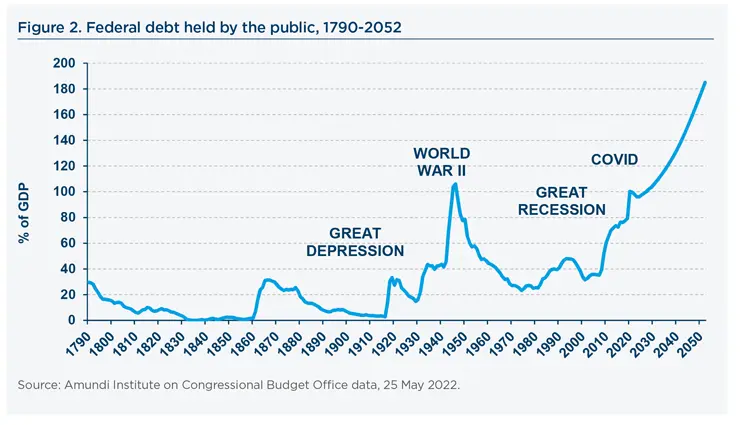

The entire debate surrounding fiscal policy is taking place at a time when debt accumulation is at historical highs (in absolute terms and also relative to GDP), with wide divergences across countries and regions.

An idea that has been spreading is that the space for fiscal manoeuvring is effectively unlimited. This notion is predicated on the fact that interest rates have been on a downward trend for decades and that if the actual safe rate r is less than the growth rate g, we can maintain debt sustainability and manage persistent budget deficits despite exceptionally high levels of debt. This amounts to the concept of a fiscal ‘free lunch’, that is, not having to repay the price of debt.

This idea is an illusion. The myth of unlimited fiscal capacity is a trap for investors and one that will have profound consequences on their portfolios in the medium term.

Similarly, it is erroneous to believe that ‘one size fits all’, common fiscal policy recommendations are appropriate, considering the highly fragmented world we are currently living in. The case of the European Union is emblematic in this respect. Precise, universal rules on the convergence of debt ratios and deficits have been shown to be unrealistic and even damaging (austerity at all costs). These rules are outdated and it is anachronistic to believe that they should be re-established. Therefore, we should not only expect greater fragmentation on the monetary front (as central banks are at different phases along the tightening cycle), but also a fragmentation of fiscal policies.

Why is the fiscal free lunch an illusion?

The fiscal ‘free lunch’ is an illusion because it is built on the consideration that interest rates have been kept artificially low through non-conventional monetary policy measures and have followed a downward trend based on structural factors. It is a narrative which aims to project a past regime into the future, based on the idea of anchored inflation expectations, such that central banks can control the yield curve forever. However, interest rate levels do make a difference, as shown by the evolution of the US debt/GDP ratio.

This false conviction of forever low interest rates has been reinforced by the regulatory framework that was established in the wake of the great financial crisis. New legislation propelled demand for safety, liquidity and high-quality assets. It made the long portion of the yield curve particularly flat, anesthetised and detached from fundamentals. Today’s curve (particularly the long end) has lost all of its signalling power, so much so that an inversion is no longer a reliable indicator of recession: for years we’ve moved beyond the idea of a ‘free market’ in this respect.

It must be noted that the downward trend in interest rates during recent history has been an international phenomenon, at least in developed markets, through synchronised central bank balance sheet expansions. Although outright rate reductions did not occur in emerging markets, these countries benefited indirectly from the compression of rates in the US (insofar as EM debt is priced in terms of a spread against Treasuries), reducing the overall cost of financing (with some idiosyncratic exceptions). At the same time, the trend was not observed in China. Here the regime opted for a balanced policy mix, in order to wean itself off of a growth model based on low added value product exports and overinvestment, towards a more sustainable model driven by internal demand and higher value chain production.

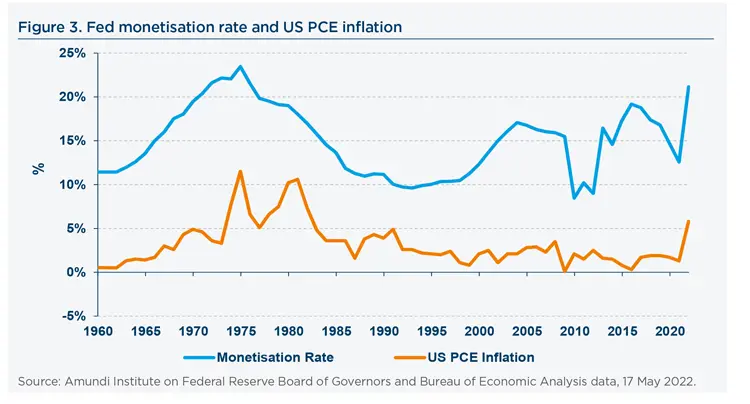

Evidently, with the notable exception of China, the world is undergoing a profound regime shift. Signs pointing towards this new narrative can be found in the resurgence of inflation, notwithstanding the fact that inflation in different countries stems from a variety of sources (bearing in mind that the composition of inflationary baskets is different across regions). Inflation in the US has mainly been driven by a tight labour market and persistent excess demand, partly retraceable to fiscal policy through liquidity injections beyond measure in response to the pandemic. In Europe, the principal inflationary forces have been inefficient supply chains and skyrocketing energy prices. In EM, the main culprit has been the price of food.

What lies ahead? The future policy mix and its investment implications

Investors tend to underestimate the fact that in a regime shift interest rates will be higher and that the margin for fiscal manoeuvring will therefore be limited. Plainly, there will not be a free lunch. Although rates will have to be adjusted, they will not increase in a synchronised and uniform manner. In fact, we are moving away from a rule-based and synchronised central bank model to a fragmented one.

This shift will have important consequences for investors. In fixed income, the year so far has been outright carnage for bond markets, characterised by elevated drawdowns and a correction in excessive bond valuations. Initially, equities proved more resilient, maintaining higher valuations in the relative value game with bonds. Most recently, however, the ongoing repricing of risk has jeopardised stocks, particularly those most sensitive to interest rate dynamics (the Nasdaq is down 28% from its November highs). Overall, investors in balanced portfolios are having to face off against a decidedly negative market performance this year, with limited places to shelter.

Proponents of the unlimited fiscal policy rhetoric also argue that the creation and bursting of bubbles (which economist Olivier Blanchard defines as ‘sunspot equilibria’) is a limited phenomenon. That is not quite the case. Other elements embedded into psychological phenomena (preferences, expectations and risk appetites for example) have bloated valuations well above the fundamentals. This phenomenon is far more frequent than commonly believed: it is precisely what has been happening on the shoulders of ultra-low (sometimes negative) interest rates and is rooted in the belief of central bank ‘magic money’ (think of the ‘Roaring 20s’ narrative).

The ongoing regime shift is catalysing a reality check regarding the overvaluation of stocks and bonds, and raising questions concerning the paradigms of the past (such as the fact that these two major asset classes should be negatively correlated).

So where do we go from here? How far along the path of bond repricing are we? For how long (and up to what point) can equity absorb elevated interest rates? These are some of the key questions investors should be asking themselves today. The answers to these questions hinge on the reaction of monetary policy to elevated inflation, as well as when (and to what extent) there will be a real normalisation of policy approaches. The 3% level has become a critical threshold not just for bonds, but for equities as well (as a proxy for risky assets).

In our view, there will not be a full-blown normalisation of policy. Central banks will remain ‘behind the curve’ and will maintain their benign-neglect bias. Faced with prioritising either growth or inflation, policymakers will focus on the former: they will not be ‘inflation killers’ at the risk of stamping out growth. Therefore, rates will remain relatively low for some time, allowing financial repression and fiscal dominance to continue. Moreover, the energy transition – as well as the consequences deriving from the war in Ukraine – will necessarily imply a higher degree of policy accommodation rather than less.

Ultimately, the 3-3.4% threshold in 10-year US Treasuries (which is comparable to a USD 3.4 trillion reduction of the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) balance sheet over the next three years, effectively neutralising what has been done so far in the way of liquidity injections to face the Covid pandemic) is beginning to look appealing for investors. Demand from investors (who, due to regulatory requirements, must look at these assets) will ensure the market self-corrects, limiting the potential for an ulterior severe correction in bonds.

Overall, we can envision three scenarios for possible future policy mixes:

- Fiscal expansion and full normalisation of monetary policy. This first option is difficult insofar as a full normalisation is a fiscal space killer. Higher rates make large debt burdens unsustainable and limit the space for further action, which may be needed in order to avoid triggering a recession, if the monetary conditions are too tight. The main risk is in timing: monetary authorities may turn off the taps too quickly and the fiscal ones intervene too late. In markets this would imply further repricing towards the downside for risky assets and particularly for stocks that are most sensitive to interest rate dynamics.

- Some fiscal expansion, with Central Banks remaining clearly ‘behind the curve’ as a cooperative move to accommodate the fiscal impulse. This is the best way to optimise the growth/inflation trade-off and to engineer a controlled slowdown in the economy: nevertheless, inflation would still be running high. In this case certain risk assets, particularly dividend equity and real assets, deserve higher exposure in order to protect against the threat of inflation.

- Fiscal expansion with full cooperation and accommodation on the monetary front. This would inevitably lead to a deanchoring of inflation expectations, with almost no place for investors to hide bar cash and real assets.

If little or nothing is done on the fiscal side, mechanically this implies a tightening in the overall policy mix, reversing the trend of the past few years. Ultimately, recession and an abrupt market repricing would be the obvious consequences.

In the medium term, the regime shift implies:

- Structurally higher inflation;

- Fiscal stimulus will still be present, but there won’t be a free lunch;

- More elevated neutral rates; r is likely to become superior to g either due to:

- An elevation of the neutral and actual safe rates engineered by Central Banks on a temporary basis, but which will prove more permanent when they are forced to become excessively aggressive, or;

- A situation of financial repression that is unsustainable over the medium term (for instance to face increasing challenges for pension funds).

Both cases are initially benign for risky assets but will eventually require a rerating of equities as (a) the nominal rate is superior to inflation, or (b) forced bond purchases require the sale of equities.

- Fragmentation of fiscal and monetary policies instead of a unique monetary policy or ‘fiscal space’ and, consequently, greater relative value opportunities and diversification;

- In equities, a tilt toward fundamentals, a re-rating of price earnings and 10-year expected returns in the range of 5-5.5% in the US market.