Summary

- Due to its high dependence on energy imports, Italy was among the European countries most affected by the conflict in Ukraine. The government’s 2023 budget measures aim to limit the effect on Italian households and firms, providing a floor to the impact of the inflation squeeze and have resulted in a better-than-feared economic outcome.

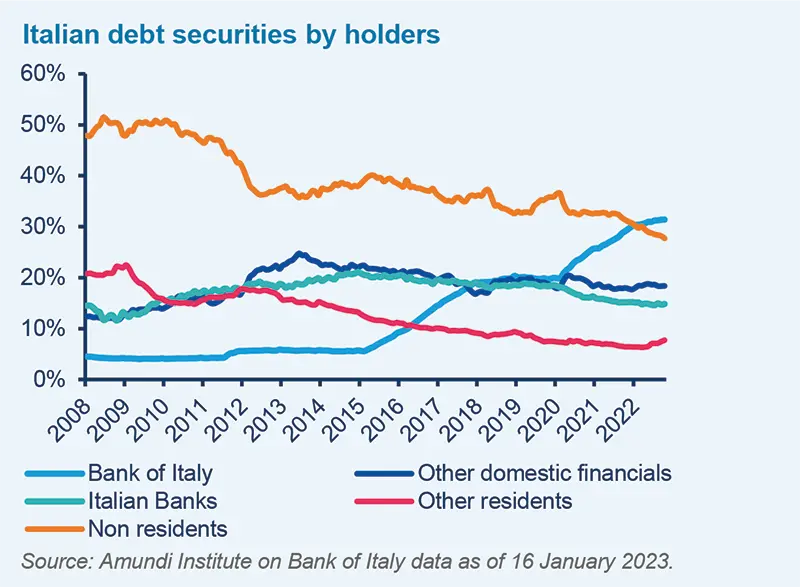

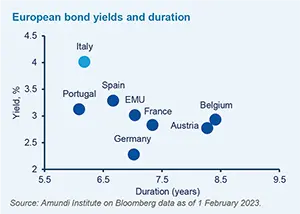

- The introduction of the new Transmission Protection Instrument, the changing structure of sovereign debtholders, and the high average maturity of Italian debt suggest there is no immediate cause for concern despite the country’s growing debt mound.

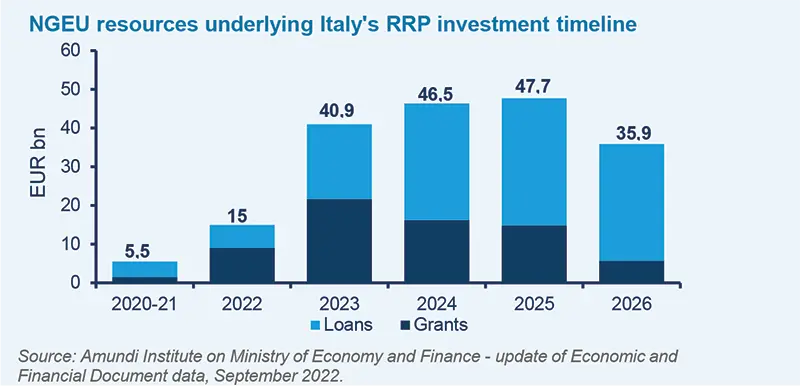

- As the largest beneficiary from the Next Generation EU (NGEU) post-pandemic reconstruction plan, Italy has a unique opportunity to modernise its economy and propel growth via structural reforms. As the third biggest economy in the EU, Italy can rely on its advanced industrial sector and healthy household balance sheets to stimulate investments.

- The Italian market presents several opportunities for investors. Government and corporate bonds represent a good source of carry in fixed-income portfolios. Equity markets are still dominated by small- and medium-cap firms, with a few relevant exceptions in the energy, industrial and banking sectors. Equities can be attractive for their high dividend yields.

- In terms of ESG, Italian firms are catching up, but the road ahead is still long. NGEU investments may create new opportunities for the development of ‘improvers’ – companies showing a consistent improvement in their governance, environmental and social practices.

Italy’s economy shows resilience, despite the energy crisis

Italy’s large dependence on Russian gas and other commodity imports left it vulnerable to the war in Ukraine. At the start of the conflict, over 40% of the country’s gas supplies came from Russia, meaning its energy sector was heavily exposed to shortages prompted by the barrage of sanctions imposed to thwart the invasion. The largely energy-driven, global inflationary spike in 2022 further complicated Italy’s economic outlook, and price rises were not matched by a similar growth in wages. Nevertheless, Italy’s economic performance surprised to the upside last year and GDP growth outperformed many of its Eurozone peers, mainly thanks to the resilience of its domestic demand, household consumption and investments, as well as external demand and exports.

Fiscal support and the return of tourism after Covid underpinned the recovery, especially in the services sector. However, in the last quarter of 2022 the Italian economy contracted slightly, with Italian GDP falling by 0.1%. Some weakness may persist throughout the first quarters of 2023, but there should be a return to modest growth thereafter. Lower energy prices will help lift sentiment and ease pressure on households and companies, providing some support for better growth by removing the risk and uncertainty of gas rationing. These positive factors could in part offset the dragging impact of tighter monetary policy and decreasing fiscal support, the effects of which we expect to start showing in the second half of the year.

Additionally, following elections in late September, the new government’s budget was passed on 29 December 2022 and was largely aligned with expectations, albeit with some minor amendments. The bulk of expansionary measures, in the region of €21bn or 1% of national GDP, are geared towards helping households and firms deal with the energy crisis. About half of this stimulus is in the form of tax credits for firms’ energy bills, while the rest includes measures to reduce VAT for energy transactions, as well as a ‘social bonus’ and other such one-offs. The government’s need to extend these measures, which only cover the first quarter of 2023, will be contingent on the evolution of energy prices and its ability to forge new alliances and diversify its energy supply in order to keep costs subdued.

The decline in global energy prices has been imperative on this front. The domestic market price of gas (on the Virtual Trading Point - PSV) has dropped substantially over the past few months. In January, the average price was around €68/MWh: a marked drop from the peaks reached last August (up to €310/MWh). Lower energy costs should help ease inflation, provide some relief to economic activity and assist the government in limiting the pressure on its deficit. Current levels already carry important fiscal savings: in Q1 alone, the government could save around €8bn on fiscal measures, relative to official estimates that were based on the gas price of €120/MWh. Overall, the Italian economy is expected to show resilience despite these extraordinary economic conditions, and to recover in line with the other main European countries starting from Q2 2023.

Additionally, while the country has historically wrestled with a vast debt legacy, several mechanisms are in place to preserve growth and ensure there is no immediate cause for concern regarding its debt burden:

- The Next Generation EU (NGEU) fund will help preserve growth in the coming years, and, to a lesser extent, will reduce the need for market funding and increase average debt duration;

- The sharp rise in CB debt holdings, coupled with relatively steady domestic demand for sovereign debt, has softened the link between foreign flows and spread volatility. The introduction of the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) also provided an important backstop, contributing to a lower correlation between ECB rate expectations and peripheral spreads;

- The high average maturity of sovereign debt (standing at 7.04 years in December 2022, close to the 2010 historical peak) has contributed towards limiting the negative impact of the current interest rate cycle on the cost of the overall debt burden, which is still quite low by historical standards.

In fact, although higher rates have made borrowing more expensive for governments, sovereign debt remains on a sound path in the near term. Inflation has pushed nominal growth higher, while debt servicing costs will take some time to catch up, meaning that countries with a higher average maturity of outstanding debt (such as Italy) have locked in lower rates for longer. This will be particularly helpful for supporting expansionary fiscal measures in light of the current and complex macroeconomic environment.

NGEU carries new opportunities to eradicate past legacies

As the largest beneficiary of the NGEU post-pandemic reconstruction plan with €191.48bn receivable, Italy has a unique opportunity to modernise its economy and subvert some of the legacies stemming from its past: from low productivity growth to high unemployment and a marked north-south divide. Italy’s Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) is financed by €69bn in grants and €122.6bn in loans contingent on the implementation of national reforms: to date, it is on track to meet its qualitative and quantitative goals.

On 30 December, Italy submitted a €21bn payment request to the European Commission for the completion of 55 targets covering reforms in the areas of competition, justice, education, undeclared work and water management, as well as investments in cybersecurity, renewables, grids, railways, tourism, urban regeneration and social policies. The RRP includes a wide range of investment and reform measures across six thematic areas or ‘missions’, with major capital allocations directed towards the digital and green transitions, and social and economic resilience measures. Implementation of the following initiatives should help:

1| Improving the ease of doing business and boosting foreign direct investments

In particular by: (i) reforming the justice system to reduce the length of civil and criminal proceedings, improving the efficiency of the justice system and reducing the backlog of pending cases; (ii) cutting through the red tape to improve the effectiveness of public administration and modernising public employment; and (iii) improving public procurement and local public services, while reducing late payments and removing barriers to competition to enhance the business environment.

2| Increasing education levels, skills, labour participation and productivity

Key sectoral reforms include those related to education and active labour market policies. These are complemented by relevant investments to increase the supply of childcare facilities, improve women’s and youth participation in the labour market, and reinforce vocational training (around €26bn planned).

3| Reducing regional disparities via investments in healthcare, housing and social services

Reforming the healthcare system envisages using new technologies to improve both hospital and home care via greater use of telemedicine that will also reduce territorial fragmentation (€15.6bn). The plan further incorporates measures to transform vulnerable territories into smart and sustainable areas by investing in social housing, strengthening local social services to support children and families, improving the quality of life for people with disabilities, and building new infrastructure in the Special Economic Zones in the south of Italy (€13.2bn).

The combined effect of these investments (direct and more immediate) and reforms (on a broader horizon) could significantly boost economic growth in the medium and longer terms. According to government estimates, the cumulated impact deriving from full implementation of the programme could lift GDP by 1.8-3.6% by the end of 2026. Potential growth would also receive a push, moving in the region of 1.1-1.3% according to official estimates, depending on the elasticity of GDP to government spending efforts.

While some of the goals outlined above have been more difficult to implement, and the process may be more back-loaded than originally anticipated, this has not necessarily been due to a lack of efficiency. Rather, public tenders were set when inflation was lower, and therefore must be revised to reflect the current environment. Additionally, administrative changes were made to speed up public tenders. These are time-consuming processes, but in 2023 the pace of spending should pick up.

Opportunities for investors

As the ECB turns away from quantitative easing and towards a modest reduction of its asset purchase programme, the situation appears less supportive for Italian government bonds in 2023, as for all Eurozone sovereigns. However, expected net debt issuance should only increase moderately compared to 2022, and less than what is expected for most core countries. Following the great repricing of bond yields, Italian BTPs and corporate bonds represent a source of carry in fixed-income portfolios (especially on the short and middle parts of the curve) thanks to their higher yield and shorter duration compared to European peers. The introduction of the TPI also limited the impact deriving from an upward repricing of the ECB’s expected terminal rates.

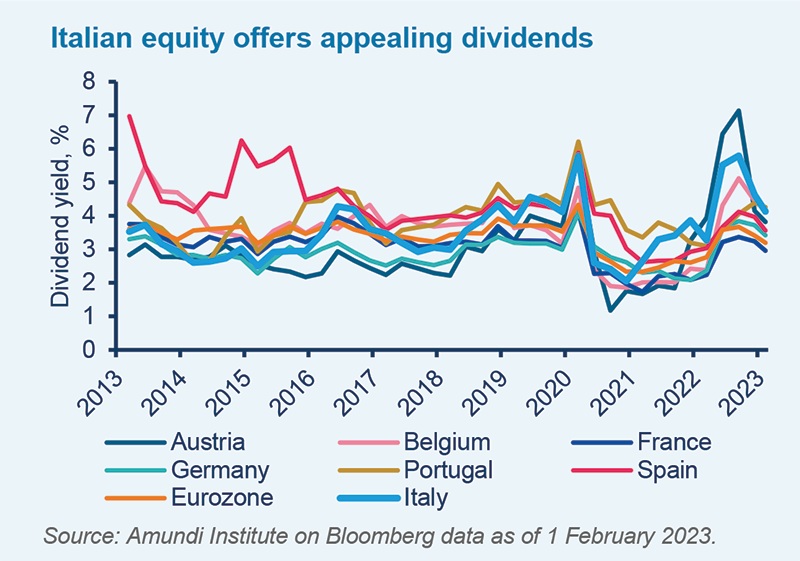

In equities, certain downside elements have yet to be resolved, including the energy crisis, the price of raw materials and higher interest rates. However, fundamental valuations seem to be discounting most of the bad news. Results in H2 2022 were generally better than expected and demand is still improving. Moreover, Italian companies’ balance sheets are in much better shape than they were during the last crisis and the NGEU will provide further market impetus. At current valuation levels, we believe Italian equities offer interesting opportunities, particularly for investors in search of attractive dividend yields, which are around 4% for the FTSE MIB Index. Careful selection remains key, but we see industrials, banking and the luxury sectors as offering interesting opportunities.

When it comes to ESG, the small- and medium-sized enterprises that constitute the bulk of the Italian market have a long way to go. Data is not always timely or accurate. This makes shareholder engagement and the integration of fundamental and ESG analysis in the company selection process even more important. Incoming equity flows should be channelled towards ‘improvers’ – companies at the early stages of their ESG journey that exhibit positive momentum – to help them set goals and move their agenda forward. Implementation of the aforementioned ‘green’-heavy RRP will also engender new and sustainable opportunities to generate sustainable returns. Moreover, a domestic market structure comprised of family-owned businesses and small enterprises represents a good hunting ground for private markets, putting capital to work in sectors such as agribusiness and supporting the development of the country’s excellence.

The Amundi Sustainable Future Indicator

The NGEU represents a marked shift in the EU’s programming policies. Its ultimate goal is to redesign the European economy via greater digitalisation, inclusion and sustainability, and to stimulate growth in the post-pandemic and conflict-stricken era. Through its vast financing endowment, the NGEU, and its incarnation in various national RRPs, is a chance to relaunch Italy and Europe, and to combat structural problems related to high indebtedness and low international competitiveness. In this sense, it is not merely a cyclical stimulus plan as it requires an analytical tool to measure its implementation and success.

The Amundi Sustainable Future Indicator, created in collaboration with The European House – Ambrosetti, leverages the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework to measure the progress of individual nations’ proposed reforms in the context of the NGEU. The indicator tracks each nation’s sustainability trajectory and measures the plan’s impacts on the social, economic and environmental fabric of each country. The indicator draws on 51 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), adapted for the European context, and condenses them into the 17 SDG pillars – ranging from social inequality to the preservation of ecosystems – to assign a score to each country.

In this framework, the picture that emerges of Italy is a mixed one. In 2021, the country ranked 24th out of the 27 EU countries. Its economic performance was particularly disappointing: it was 26th for ‘decent work and economic growth’ (SDG 8) and 24th for ‘industry, innovation and infrastructure’ (SDG 9). The country’s high rate of long-term unemployment also highlights the inefficiency and rigidity of its labour market. Likewise, its performance in educational categories – a good proxy for measuring a country’s future success – was subpar.

Nevertheless, Italy outperformed its peers in many other indicators: it ranked first overall in ‘zero hunger’ (SDG 2), fifth in ‘good health and wellbeing’ (SDG 3), and second in ‘responsible consumption and production’ (SDG 12). It also had the lowest rate of obesity and among the highest rates of life expectancy in good health, testifying solid foundations on which to build a more inclusive and efficient healthcare system.

Improvements in a country’s performance are the result of an intrinsic, system-wide transformation, rather than any single and immediate action. Any legislative change, whether aimed to support the energy transition or reduce inequality, can only be as effective as the public administration promoting it. This indicator can help policymakers, investors and citizens track RRP implementation progress and shape decisions for the future.