Summary

China: pressure before parley

Key takeaways

Beijing’s approach to the trade war has shifted dramatically; where it once favoured restraint and dialogue in Trump’s first term, it now responds with decisive retaliation.

Washington’s drumbeat of ‘strategic decoupling’ has strained trust, leading Beijing to adopt a more guarded and hesitant stance toward engagement, lowering the odds of meaningful negotiation.

Facing multiple contingencies, Beijing will likely lean towards an all-weather strategy: calibrating domestic economic buffers, expanding Global South partnerships, and selectively engaging with U.S. allies—while deprioritizing deals with Washington.

Impacts of the trade war are just about to unfold, and some are not erasable by whimsical policy changes. It is complacent to assume there will be no structural consequence.

While mitigation plans may work for 30% tariffs, rates exceeding 100% are impossible to mitigate—even for businesses with high margins and strong pricing power. By imposing a high punitive tariff rate of 145%, Washington is dangerously flirting with the idea of economic decoupling. Even temporary adherence to this unsustainable rate has significant consequences.

The impacts are three-fold:

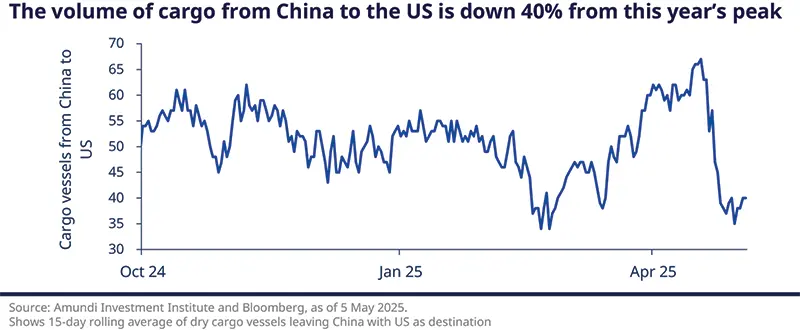

First, a supply shock as transpacific shipments halt and orders are cancelled; this, however, is borne more by the US than by China. While the number of vessels carrying containers to the US is expected to decline sharply, China’s port throughput has increased in both sequential and annual terms since 9 April. Reported increases in shipping demand in Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia, and rising traffic to Europe are not coincidences, indicating rerouting by Chinese exporters.

-

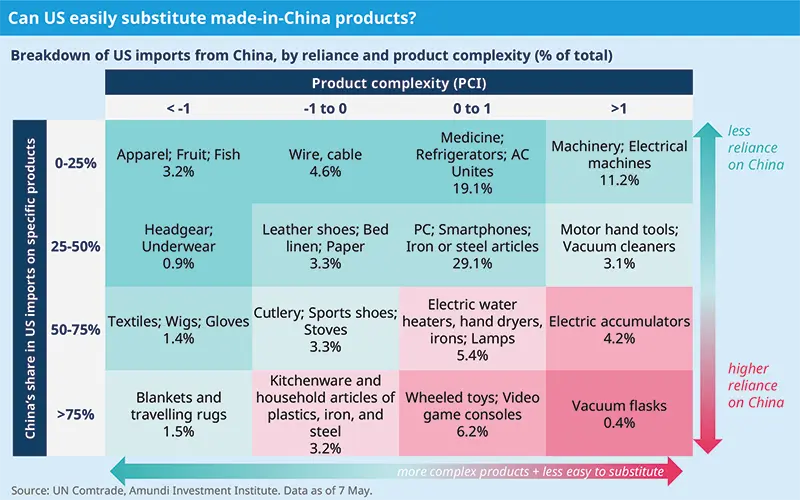

Among the top 100 products that are hardest to substitute, China on average accounts for 57% of the world's total exports.

Second, a demand shock, as punitive tariffs start to take a toll on consumers and corporate profits, in both the US and China. The costs of tariffs will be borne by Chinese exporters, US importers (such as Walmart, Home Depot, and Target), and US consumers. Approximately a quarter to a third of US imports from China are difficult to substitute. This is due to the heavy reliance on Chinese supplies in the US, the complexity of certain products, and China’s position as the sole or one of the few producers. Among the top 100 products that are hardest to substitute, China accounts for an average of 57% of the world's total exports (see table below).

Finally, a structural shock, as companies adjust supply chains to accommodate increased protectionism, exchanging efficiency for policy security. Since US retailers sourcing from China have experienced considerable damage from supply shortages, these risks are no longer economically justifiable.

Mutual de-escalation happened quickly, allowing tariffs to fall from the highly-punitive 145% to 30%. Together with the initial tariffs under Trump’s first term, the effective US tariffs on Chinese imports are close to 40% - which are much higher vs Trum 1.0 and still prohibitive. Chinese exporters, on average operating with relatively low margins, have no effective way to mitigate the impacts on their own.

Mitigating amid multiple contingencies: amid the evolving tariff landscape, the bar for resuming monetary policy easing is lower compared to other measures. Rate cuts were already needed before Trump took office, to assist the fragile recovery in domestic demand. Restrictive US trade policies will act as a disinflationary demand shock to China’s economy, further worsening the existing deflation issue.

On 7 May, the PBoC cut the RRR by 50bp and the policy rate by 10bp. We expect two more cuts of 10bp each in July and September, respectively.

For fiscal policy, however, Chinese policymakers might prefer to wait and assess how damaging the trade war is before taking decisive action. It has only been two months since the fiscal stimulus package (approximately 2% of GDP) was introduced by the National People’s Congress.

Q3 will provide a good opportunity to evaluate the need for a supplementary budget, with May and June data available for a better assessment of the impacts.

Playing the long game, China has no time constraints in this fight, unlike Trump with the upcoming mid-term elections, allowing Beijing to adopt a strategic approach. China’s economic warfare arsenal comprises three arrays of tools:

Offensive measures: these aim to retaliate and inflict pain on the rival, such as restricting access to critical Chinese supplies like rare earths (i.e., through its own export control), and gatekeeping access to China’s market (punitive retaliatory tariffs, regulatory investigations, and government procurement rules). Selling US Treasury holdings would be ineffective as an offensive market measure. Even if all of China’s FX reserves ($3.2 trillion) were invested in US Treasuries, the sheer size of the Treasury market— with daily trading volume exceeding $900bn—means China’s rapid liquidation would be absorbed within 3-4 days, limiting any lasting market impact. Not to mention that the Fed has multiple liquidity tools to mitigate Chinese selling pressures.

Defensive measures: these are designed to mitigate the negative effects of potential attacks, particularly in the financial market, where the US holds a clear advantage in blocking China's access to the dollar-dominated global financial system. FX reserve divestments, cross-border payment arrangements, RMB settlement infrastructure, and central bank swap lines will progress further and faster.

Remedial measures: these involve concessions and positive moves, such as re-engaging in negotiations with the US, deepening trade ties with US allies through multilateral agreements like the CPTPP and strengthening partnerships with the Global South. In this context, traditional tactical tools that could hurt strategic goals— export subsidies and currency devaluation—will likely be set aside.

Key take-aways on China’s equity market from the desk

We maintain a long-term positive view on China, considering the recent significant shift to supportive fiscal policies. However, given the extreme uncertainty on the tariff side, we are more cautious in the short term, and we think it's time to pivot towards more domestic and defensive areas that are less impacted by tariffs.

As such, we favour the onshore market (China A-shares) over offshore market (China H-shares) and domestic demand and dividend yield over export-oriented exposure, given the more geopolitically resilient risk premia in the onshore market and the government's focus on stimulating domestic demand.

In China, we are seeing positive momentum in earnings within the tech sector, particularly with the rise of AI applications and consumer technology. Nonetheless, we remain cautious about the risks of increasing overcapacity in China and the potential dumping or displacement of existing products in global markets, which would pose challenges for both domestic and international players.

NICHOLAS MCCONWAY, HEAD OF ASIA EX-JAPAN EQUITY, AMUNDI

US and China: managing a deteriorating relationship

The relationship between the US and China will likely continue to deteriorate, as the US security establishment considers 2027 as the key date for China to be able to take on the US.

However, the US and China have little interest in allowing their relationship to completely spiral, preferring instead to achieve an economic divorce that allows both countries to survive. Recent tariff reductions reflect these dynamic.

Although trade tensions between the US and China have now eased, it is important to understand the broader dynamic between the two countries. Over the next few years, the US-China relationship will continue to deteriorate, with 2027 seen as a key date on the horizon. This is the year the US security establishment believes China could be in a position to militarily challenge the US. Whether or not this is accurate, these fears are driving US policy towards China as well as US efforts to re-industrialise. To wage and win wars, a country must have a solid industrial base to build and repair military equipment. Trump’s steel, aluminium and China tariffs must be seen from this perspective; they also aim at weakening China’s industrial capacity.

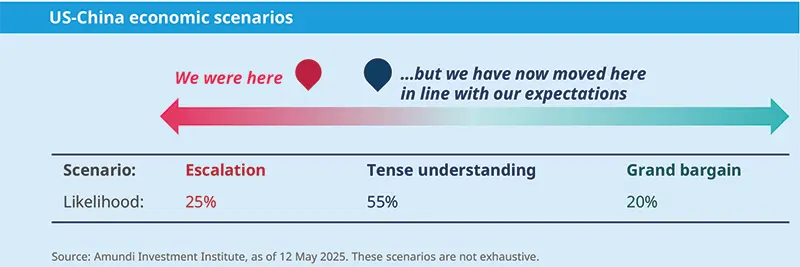

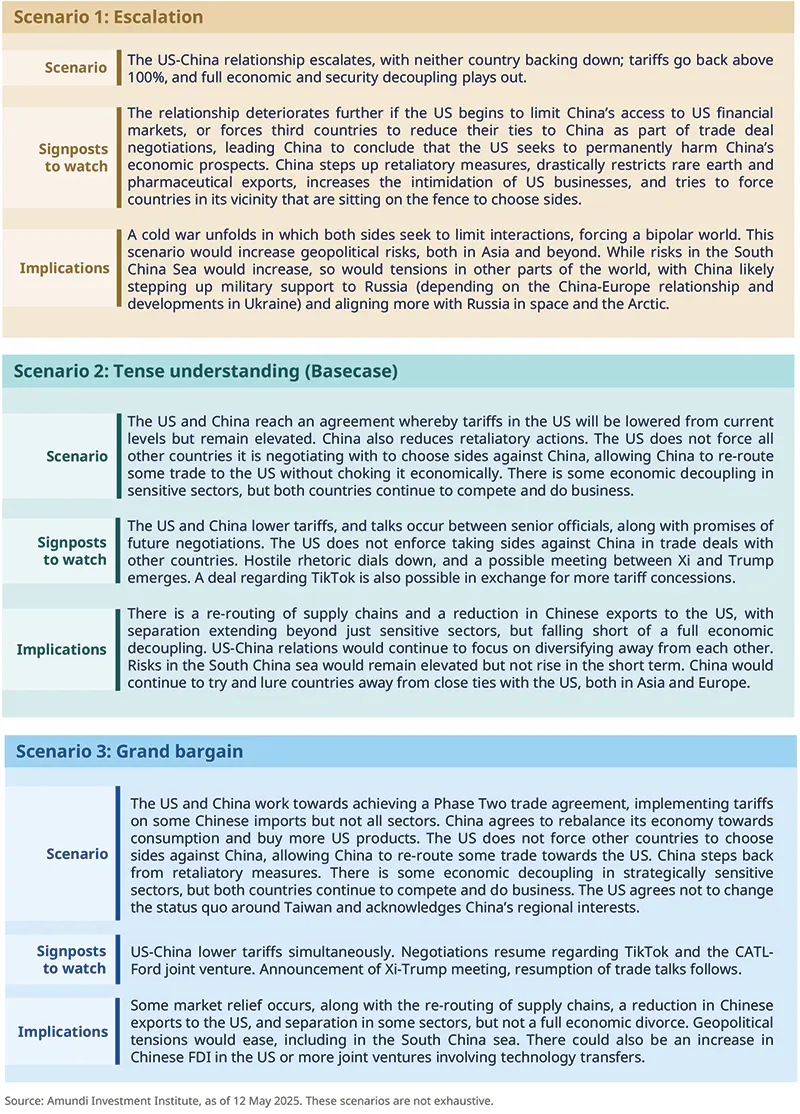

That being said, in 2025, the US and China have little interest in allowing their relationship to spiral out of control: it is about achieving a divorce that still allows both parties to remain economically afloat. We are now seeing both sides walk back on tariffs. The scenarios outlined below show how the relationship has evolved from the ‘escalation scenario’ to our basecase, the ‘tense understanding scenario’, in which we expected US-China tariffs to fall significantly from the previous 145% level. While further talks are possible, we do not expect a ‘grand bargain’ anytime soon. During Trump’s first term, US-China trade negotiations proved difficult and took years to complete.

In 2025, the US and China have little interest in allowing their relationship to spiral out of control: it is more about achieving a divorce that still allows both parties to remain economically afloat.