Summary

Executive summary

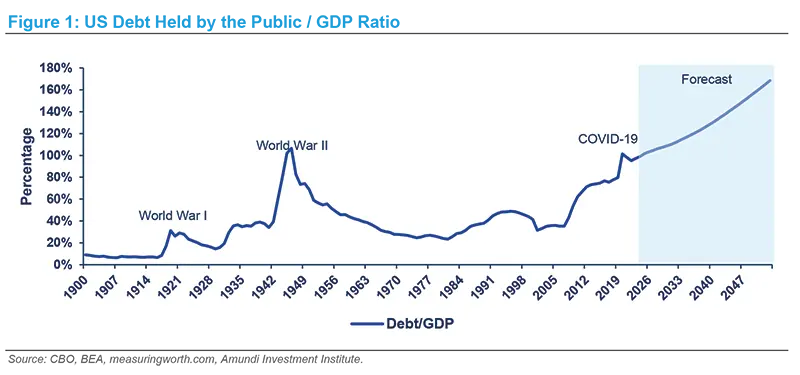

The United States is approaching an unprecedented level of debt, exceeding historical highs experienced post-World War II. This situation indicates that fiscal adjustment is unavoidable, as the country cannot simply outgrow its debt dilemma. Despite high domestic and external demand for US debt, relying on this demand amid such significant debt increases is risky.

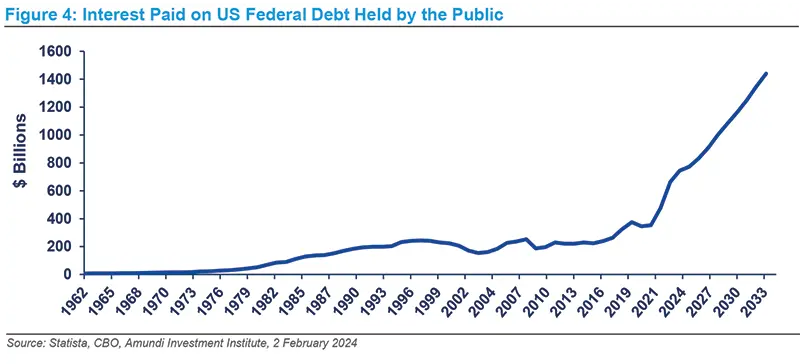

The trajectory of US federal government debt is escalating, with debt held by the public potentially rising from just under 100% today to more than 170% of GDP in 30 years. This raises concerns about the feasibility of financing and the associated costs. The end of low interest rates could lead to a higher portion of tax revenue dedicated to debt service, higher inflation, and possibly stifling economic growth.

Historical data suggests a weak relationship between the supply of federal debt and the interest rates charged. However, this relationship may not hold with the current rise in debt levels. The lack of strong growth prospects to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio and the absence of political willingness for fiscal adjustment present significant risks. As a result, investors should anticipate higher term premiums in US debt markets.

Two scenarios of fiscal adjustment are explored: gradual fiscal consolidation and forced abrupt adjustment. The former would involve a slow increase in yields, leading to political consensus for spending cuts and tax increases. The latter, driven by a more sudden loss of investor confidence and market disruptions, could result in significant global repercussions. In either case, the Federal Reserve may be required to support US bond markets, although its actions could be less effective in a high-inflation environment with diminished confidence in US debt.

The path to a more stable fiscal outlook for the US is expected to be significantly more volatile than what markets have witnessed over the last ten to fifteen years.

A Rising Trajectory

US federal government debt is on a rising trajectory. It is estimated that debt held by the public could increase from just under 100 percent of GDP today to more than 170 percent in 30 years1. Can this be financed, and at what cost?

The USD’s privileged reserve currency status and the United States’ dominant share of global capital markets will ensure the US Treasury retains market access, but the end of the low interest rate period will entail costs. Higher real interest rates will raise the share of tax revenue taken up by debt service, high fiscal deficits may keep inflation high, and, more importantly, high debt and deficits could also reduce growth.

The US debt burden has been high before, particularly after World War II, but soon it will venture into unchartered territory. A sanguine view, based on past empirical evidence, is that there is not a strong relation between the supply of federal debt and the interest rate charged on that debt.

However, this weak relation may not hold when debt levels rise well above previous highs. Unlike the post WWII era, current projections do not indicate a future of much stronger growth that could reduce debt as a proportion of GDP. Even if the debt burden can be sustained, it would be prudent to guard against the risks of an adverse outcome.

With no indications that either political party is willing to entertain the necessary fiscal adjustment, rating agencies have periodically taken note2. In an election year, it is not expected that either party will be willing to discuss long term policy adjustments necessary to limit the increase in debt.

Over time, investors should expect a higher term premium in US debt markets than what has been experienced in the last ten to fifteen years, marking the end of the era of low borrowing costs for the US government.

To better understand the scale of the US debt dilemma, the following section provides an illustration of the key variables that underpin debt sustainability assessments.

1 US public debt amounts mentioned in this note are amounts of US federal debt held by the public. This excludes holdings by the federal government of its own debt and is the metric on which the public debate and the economic profession usually focus. In its February 2024 Budget and Economic outlook, the Congressional Budget Office projects debt held by the public to reach 172% of GDP in 2054.from 97% in 2023.

2 In July 2023, Fitch downgraded US public debt from AAA to AA+. In November 2023, Moody’s cut its outlook, from stable to negative, on the last AAA rating enjoyed by the US at one of the three main agencies.

Debt Sustainability: Deficits, Growth, and Interest Costs

A country can sustainably finance its debt if its debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to stabilize at a manageable level over the medium to long term, without straining its public finances or severely limiting public revenue for discretionary expenditure and for expenditure on committed programs (such as social security, pension provision, healthcare, and defence).

The room for public expenditure depends on how much of its tax revenue is taken up by the cost of servicing its debt (interest/revenue) and, relatedly, debt service as a share of GDP (interest/GDP).

Additionally, if deficits and the debt burden increase interest rates and market expectations of future interest rates, this could also curtail (crowd out) private investment and thereby reduce future growth.

Part of the debt can be monetized in some circumstances, such as the long period of Federal Reserve asset purchases after the Global Financial Crisis. However, this is not a feasible or particularly effective option when inflation is not unusually low. Its inflationary consequences could risk simultaneously raising long-term interest rates and the government’s debt service costs.

Beyond these long-term criteria for assessing debt sustainability, in the US, there are also material shorterterm financing risks due to the political gridlock on passing annual budgets. This can occasionally question the US Treasury’s ability to meet its debt obligations and distort yield curves as the Treasury resorts to short-term fixes.

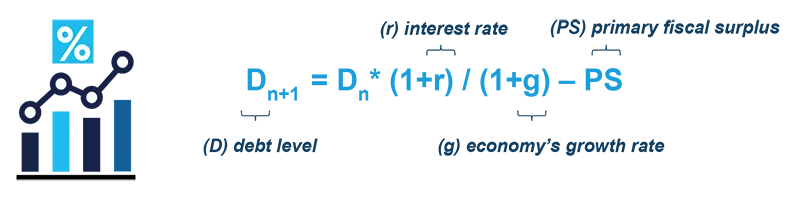

Formally, the evolution of the debt level (D) is influenced by its initial value (close to 100% of GDP today for debt held by the public), the interest cost (r), and the difference between the debt’s interest rate and the economy’s growth rate (r – g).

When r is greater than g, the government’s tax revenue will not keep pace with its interest costs so it will need to run a primary fiscal surplus (PS). For the last few years, growth in many advanced economies has been higher than the unusually low level of interest rates (low inflation and very accommodative monetary policy).

This favorable dynamic has begun to shift, with interest rates increasingly unlikely to remain lower than the growth rate on a persistent basis.

In the event of a rising debt trajectory triggering higher interest rates (creating a vicious cycle), the government would be compelled to run increasingly larger primary surpluses to keep the debt-to-GDP ratio stable.

The Long-Term Fiscal Dilemma for the US

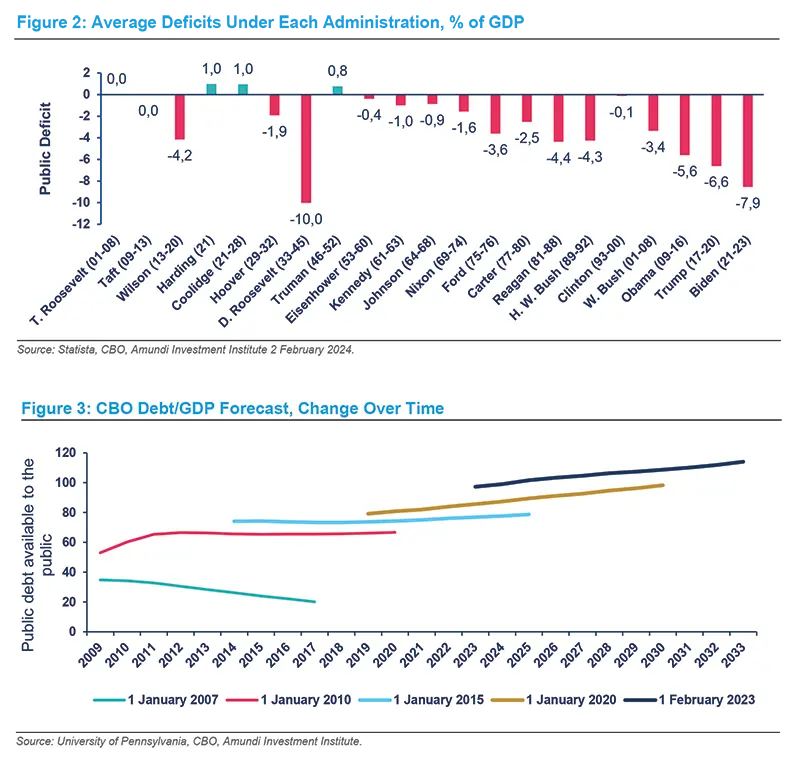

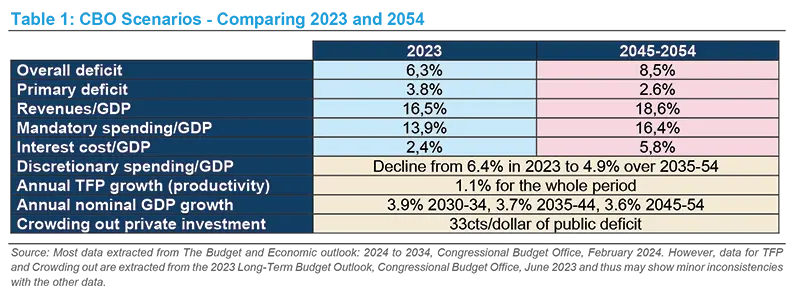

The non-partisan US Congressional Budget Office (CBO), known for its objective economic analyses, provides long-term projections for deficits and debt based on current policies, including announced future policies. Due to the absence of any significant fiscal commitments by either party to address this issue, the CBO projects a continuous multi-decade rise in debt-to-GDP ratio – from just below 100 percent today to more than 170 percent by 2054.

Recent revisions reflect increased deficits due to tax cuts under the previous administration and policy responses to the pandemic, including the associated lockdowns.

Debt service costs are expected to rise significantly over the next 30 years.

The ratio of interest costs to revenue is projected to increase from 15 percent to 31 percent, while interest costs as a proportion of GDP will rise from 2.4 percent to close to 6 percent by the 2045-2054 period.

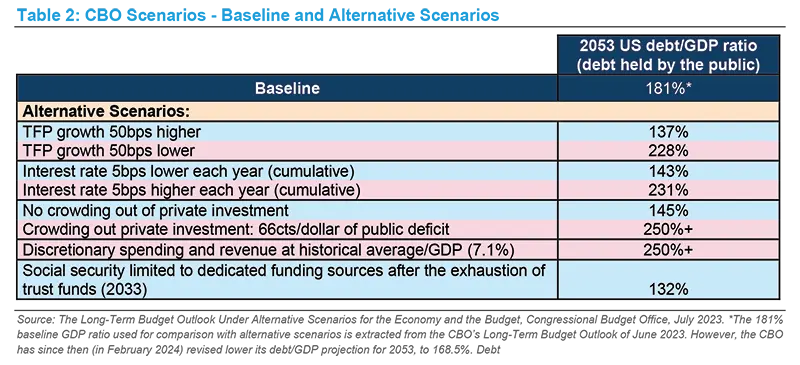

The reason for these large increases in debt metrics is largely due to political unwillingness to reduce the government’s primary fiscal deficit, which the CBO sees as remaining around 3 percent of GDP. The tables below show the CBO’s long-term assumptions regarding interest rates and economic growth, as well as longterm projected metrics under alternative scenarios. But even under slightly more favourable but plausible assumptions, such as a 50 basis points increase in Total Factor Productivity -- a substantial jump compared to US historical -- and no increase in interest rates, the debt to-GDP-ratio is still projected to exceed 140% by 2054.

For US debt to be deemed sustainable in the long term, it would necessitate implausibly high increases in potential growth, dependent on similarly unlikely surges in productivity growth, or even more implausibly, perpetually low levels of real interest rates on a secular basis.

Perpetually large deficits and rising debt levels are extremely unlikely to be consistent with sustained low borrowing costs for the US government.

Despite these concerns, external demand for US debt and US assets remains high, largely due to the pivotal role of US Treasuries in the global financial system, acting as the largest safe asset and largest collateral asset backing global financial transactions, coupled with the US’s relative growth performance. However, it would be imprudent to ignore the potential for these unprecedented increases in debt to necessitate fiscal adjustments, potentially leading to reduced US growth, as many experts argue.

Assumptions for the CBO’s main scenario are:

What Gives? Fiscal Adjustment Inevitable

Ruling out the unlikely scenario where growth consistently exceeds interest rates – the ‘goldilocks’ scenario – the US cannot grow out of its debt dilemma. This implies that fiscal adjustment is inevitable at some stage, ultimately necessitating difficult choices, even though they currently might seem politically unpalatable.

Various adjustment scenarios are conceivable, each balancing expenditure reductions and tax increases based on what is politically feasible, and importantly, how much time and space markets permit.

It is possible that the adjustment could be gradual, extended over a long period, with markets remaining patient as long as there is some political effort to implement measures that would change the long term-debt projection. However, not all viewpoints are as optimistic.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget perceives mounting pressures for near-term adjustment with little leeway for delays:

- For example, the Social Security’s Old Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund (OASI) is expected to run out of reserves by 2033.

- This insolvency would imply an over 20 percent reduction in social security benefits across the board, unless there is a political agreement to replenish this retirement fund.

With Social Security and major healthcare spending already comprising a very large share of mandatory public spending, and set to rise further due to ageing (rising c.11% in 2023 to more than 14% % in 2045-2054, according to the CBO), it is inevitable that adjustment will need to include both tax increases and expenditure reductions, likely including raising the retirement age.

With regard to discretionary spending (6.4% of GDP in 2023), defense spending (3.3%) accounts for a large share, and in the current geopolitical environment it is difficult to see room for any sizeable reduction.

Though currently unpopular and politically unpalatable, higher capital gains taxes and indirect taxes on consumption may be the most growth-friendly way to raise revenue. Additionally, a more effective corporate tax take would also help.

US Fiscal Adjustment: Gradual or Abrupt?

In principle one can imagine many scenarios of how this might play out. To highlight the potential market impact, we consider two plausible paths toward debt sustainability:

The trigger in this case would be progressively higher yields over several years, due to rising supply and domestic political pressures on fiscal trade-offs. Higher yields would crowd out more of the fiscal space available for major discretionary and non-discretionary spending programs. At the same time, rating agencies would continue to downgrade US public debt, to the point that this would become an adverse factor for global fund managers, unlike previous downgrades.

- Due to this unpalatable combination, fiscal consolidation would assume more urgency in the political domain and there would be more public acceptance of necessary adjustment. In this relatively benign scenario, political consensus would lead to gradual but resolute spending cuts and tax increases.

In this scenario, the US would go through a combination of events that would force deficit-reducing fiscal measures. The trigger here could stem from any number of sources:

- Investors might suddenly lose confidence, primarily due to significant deterioration in the debt outlook, or other fiscal-related events such as continuing political impasse on debt ceiling negotiations, frequent government shutdowns, and related disruptions to market functioning.

- Markets might lose confidence in US debt due to concerns about the nation’s global leadership role, and its fiscal ability to deal with adverse geopolitical events. Limited fiscal space to deal with domestic shocks. A shock similar to the recent pandemic, or major supply chain disruptions that lead to a significant economic downturn would call for a large fiscal response, inevitably increasing the deficit and debt. With a higher initial level of debt, such a fiscal response would only be feasible if markets are reassured of sufficient longer term fiscal adjustment underway.

Both scenarios imply inevitable fiscal adjustment. Higher yields that incentivize gradual adjustment would be more palatable for markets, whereas a sudden stop – the abrupt adjustment – would entail a substantial rise in yields and significant market disruptions that would entail material global spill overs. In either scenario, the Federal Reserve would likely be drawn in to stabilize markets. However, beyond curtailing its current Quantitative Tightening (QT) program, launching another Quantitative Easing (QE) program may not be as effective in an environment of higher inflation and lower market confidence in US debt.

Investment Implications

The timeline for when there might be a stronger willingness to begin fiscal adjustments, or when market pressures gradually increase to prompt some action is clearly uncertain. At this stage, with inflation expected to decline and longer-term yields still above our assessment of fair value, the issue of debt sustainability is not a priority.

Furthermore, currently, there is little incentive for either political party to address this longer-term fiscal dilemma. Notwithstanding periodic bouts of volatility in yields and market concerns about a higher supply of debt, we believe this issue will gradually become more prominent, especially in a longer-term time frame beyond 2030. By then, there should be some clarity on the political willingness to tackle fiscal adjustment and some of the social security and healthcare funding needs will assume more urgency.

In the short to medium term, we expect more technocratic pragmatism to deal with the political impasse:

- To accommodate market pressures, it is likely that the US Treasury will periodically pivot towards increased short-term funding through Treasury Bills (T Bills) and away from long-term bonds. Importantly, as we have argued elsewhere3 , with the rise in US debt issuance, the Federal Reserve is likely to scale back its QT program and maintain a balance sheet close to it current holdings of US treasuries.

Over the longer term, a higher supply of debt – with CBO projections indicating an increase from the current level of $26 trillion to more than $48 trillion by 2034 (debt held by the public) – is expected to increase the term premium, as investors get more concerned about holding longer-term debt.

This scenario should, in principle, also incentivize fiscal adjustment and avert a major ‘debt crisis’ or significant market disruption, though such an adverse outcome cannot be ruled out at this stage.

Our central case – that something has to give – also implies that US Treasuries will retain their status as a safe asset and their central role in global financial markets. However, the path to a more stable fiscal outlook for the US is expected to be significantly more volatile than what markets have witnessed over the last ten to fifteen years.

3 See Central banks’ endgame: A new policy paradigm. Themes in depth, Amundi, Mahmood Pradhan, Lorenzo Portelli, and Tristan Perrier, October 2023.