Summary

Resilient but unloved

We thought the banking sector was forever changed by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC): e.g., lower leverage, better risk management, greater transparency, etc. Yet, the Greensill Capital bankruptcy, and the multibillions in losses plus dividend cuts, capital increases, and senior management layoffs at Credit Suisse -- following the Archegos debacle and the Wirecard accounting fraud -- bring back a bitter taste of past troubles. It would be unfair though not to recognise that the financial system and banks in particular managed their way through the Covid-19 crisis, the largest economic shock in modern history, thanks to the efforts made over the past decade to improve their robustness.

Like the GFC, the Covid-19 crisis led to change. Banks had to achieve a turbo charged migration towards digital in a couple of weeks. Despite the huge constraints brought about by lockdowns, most banks managed to serve their clients thanks to their IT infrastructures. In Europe in particular, they have been one of the key conduits of government support to households and corporates. The 2020 earnings reporting season showed that banks in general were able to navigate the shock with so far limited casualties.

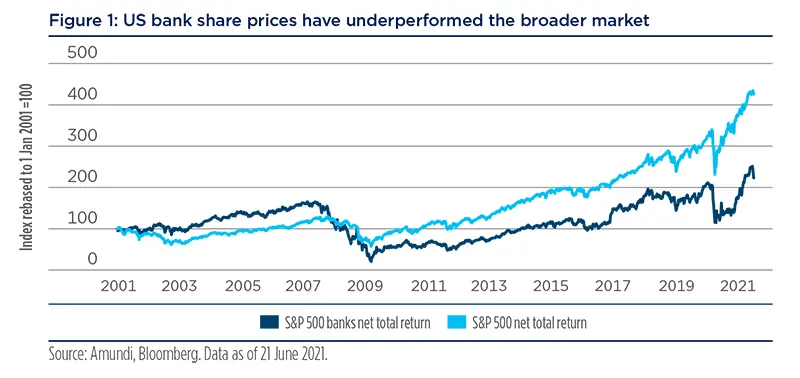

Despite this resilience, European banks’ listed shares are trading at low multiples in absolute and relative terms. Valuations of banks reached all-time lows in 2020 on a price/book value basis. The main listed banks in the Eurozone are currently trading at 0.7x their tangible book and below 9x next year’s earnings1. These low valuations imply that banks’ returns will remain structurally below their costs of capital and that in aggregate the risks and costs of running these businesses overwhelms future profits.

However, there are significant valuation dispersions within the broader financial sector universe, with fintechs trading at high multiples whereas traditional banking has been penalised by a lack of investor interest. There is a de facto premium for the disruptor versus the disrupted, which clearly shows that there is value in the sector.

Banks’ business models are under attack on all dimensions, from client services, lending, asset gathering or payments. Regulations that are more stringent have increased their cost bases and limited their nimbleness. Big banks are often compared to dinosaurs, which will not survive the digital revolution in a lower-for-longer yield environment. It is sometimes argued that banks are not needed any longer in a digital age, where peer-to-peer lending will become the norm, not the exception; where digital currencies do not require bank accounts for payments; and savings can be directly managed via mobile apps. Zombie banks would wander in a fully disintermediated world -- obsolete creatures of the past.

We think that financial systems need banks to function properly, and we believe that the core purpose of banking, which is the safeguarding of assets and the creation of money via lending, will be their sole prerogative in the future.

A more balanced view is warranted though, as many financial institutions are reinventing their business models and improving their client services thanks to digital. Moreover, we think that financial systems need banks to function properly, and we believe that the core purpose of banking, which is to safeguard client assets, gather and protect information and create money via lending, will be their sole prerogative in the future. In Europe, the main hurdles for banks are actually not digital but the unfinished banking union and the competition between different types of institutions.

In this paper we try to address the implications of the Covid-19 crisis for the European banking sector in particular. We highlight that the lack of nimbleness and adaptability in an environment where tighter regulation hasn’t been balanced by larger revenue opportunities which justifies the segment’s lack of attractiveness for investors but not banking as a business per se. We think that despite the identified challenges, the sector offers interesting investment opportunities on a selective case-by-case basis.

The banking sector muddled through the Covid-19 crisis

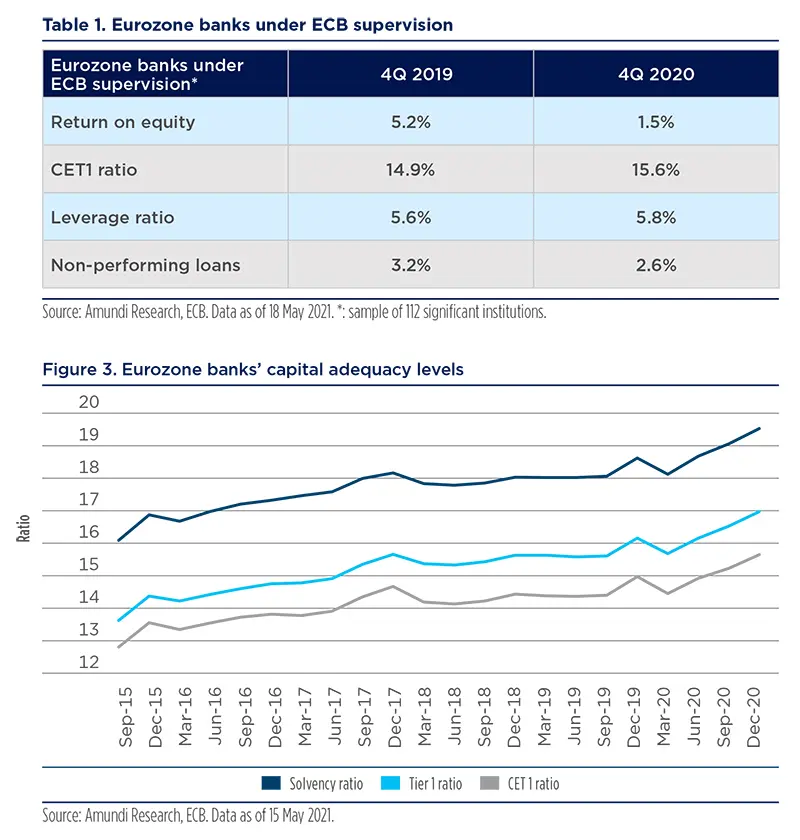

Lockdowns and sanitary measures had an extreme negative effect on the global economy. GDPs have shrunk by 5-10% across advanced economies, where the banking sector is most developed. Post the GFC, the Covid-19 crisis was a live test of the resilience of banking sectors and the financial system overall based on the new regulatory framework. Capital adequacy measures have steadily improved over the last decade and in particular since 2015 (see figure 3). Reporting for 2020 actually showed that banks’ balance sheets resisted the shock and that banks managed to muddle through. As table 1 shows, Eurozone banks’ return on equity fell four-fold in the fourth quarter of 2020 compared to pre-crisis levels, but CET1, leverage and nonperforming loans as a share of total asset actually improved.

Reporting for 2020 actually showed that banks’ balance sheets resisted the shock and banks managed to muddle through.

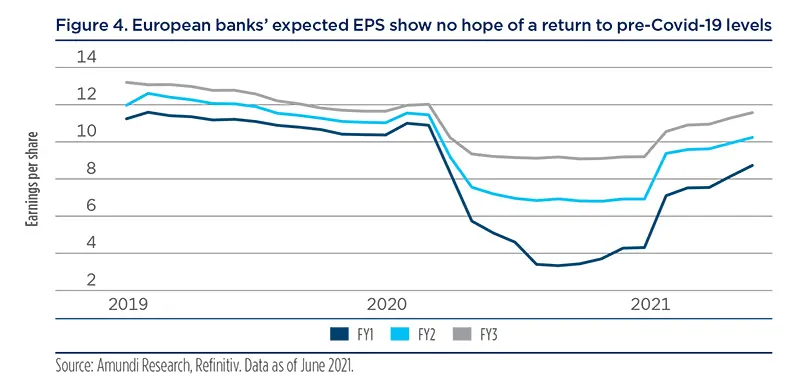

Most banks made significant loan loss provisions in the middle of the year, including technical provisions as a function of GDP changes, which happened to be too conservative either because economic activity rebounded over the second semester or because state guaranteed loans and furlough schemes assisted in the avoidance of corporate and household defaults. IFRS9 rules, which define financial instruments valuation methodology (mark to market), calculations for impairment and hedge management, have increased the pro-cyclicality of banks’ balance sheets and risk management. Central banks played a role in ensuring markets liquidity via asset purchase programmes, including corporate credit and lower policy rates in order to reduce solvency risks (TLTROs in the Eurozone). Support from public guarantee schemes limited and smoothed the impact on banks’ P&Ls. Yet, Q4 2020 and Q1 2021 results delivered a significant beat to consensus profit expectations before tax mainly driven by lower-than-expected credit losses and provisions. Contingent convertible (Cocos) spreads rose, but in line with other European banks’ funding instruments. In addition, the sector guidance for 2021 is for a meaningful decline in loan loss provisions, which should fall well below 2020 levels. In Europe, banks’ earnings per share are expected to rise by 30% this year and then by 20% in 2022. Yet, as figure 4 shows, consensus earnings expectations are below pre-crisis levels for the next four years. ECB restrictions on earnings distributions to shareholders will be lifted on 31 September 2021 and analysts expect to see special dividends paid at the end of this year for many institutions.

Banks have so far managed the crisis well and protected investors’ and clients’ vested interests, thanks to more conservative risk management and legitimate institutional support.

The pandemic is not over yet and it is probably too early to confirm that there won’t be another phase of turmoil post government support, with rising defaults and unemployment negatively affecting banks’ balance sheets and profits. One could argue that it wasn’t a credit-driven shock -- hence the limited impact on banks -- and/or that defaults may well still come. But de-risking policies and adequate asset quality management helped mitigate the economic shock. Banks entered the crisis well positioned to absorb losses. Our central scenario assumes a gradual recovery with diminishing risks over the next two years. Moreover, rising interest rates, although constrained by central banks, will support bank profits going forward. Therefore, we think it reasonable to assume that in 2023, banks’ earnings could return to pre-Covid-19 levels.

| Point 1: Banks have so far managed the crisis well and protected investors’ and clients’ vested interests, thanks to a conservative risk management and legitimate institutional support. |

Technology saved banks during lockdowns

Digital is often seen as the ultimate threat to traditional banking, i.e., regarding high transition costs, fintech competition and low customer retention. The Covid-19 crisis has been a catalyst for a dramatic change towards full digital banking operations. Transitions planned to occur over years were achieved in weeks.

Among the various implications of lockdown and social distancing is the inability to provide face-to-face service in a closed office. Although most banks were already offering online services and mobile banking applications, the bulk of service was provided in situ. Customers could not visit their bank for basic or complex operations or meet their account manager. In a blink of an eye, online service became the norm and digital replaced paper. Let us assume the same pandemic occurred 20 years ago, corporate clients would have struggled to pay bills, receive sales revenues, and pay wages while households would have had to limit payments. During this crisis, banks in Europe have been able to maintain operations and service clients regardless of restrictions and have been able to significantly limit their operational risk in a reduced control mode. Banks were basically saved by technology this past year.

The Covid-19 crisis has made digital banking an ongoing focus.

| Point 2: The Covid-19 crisis has made digital banking an ongoing focus. |

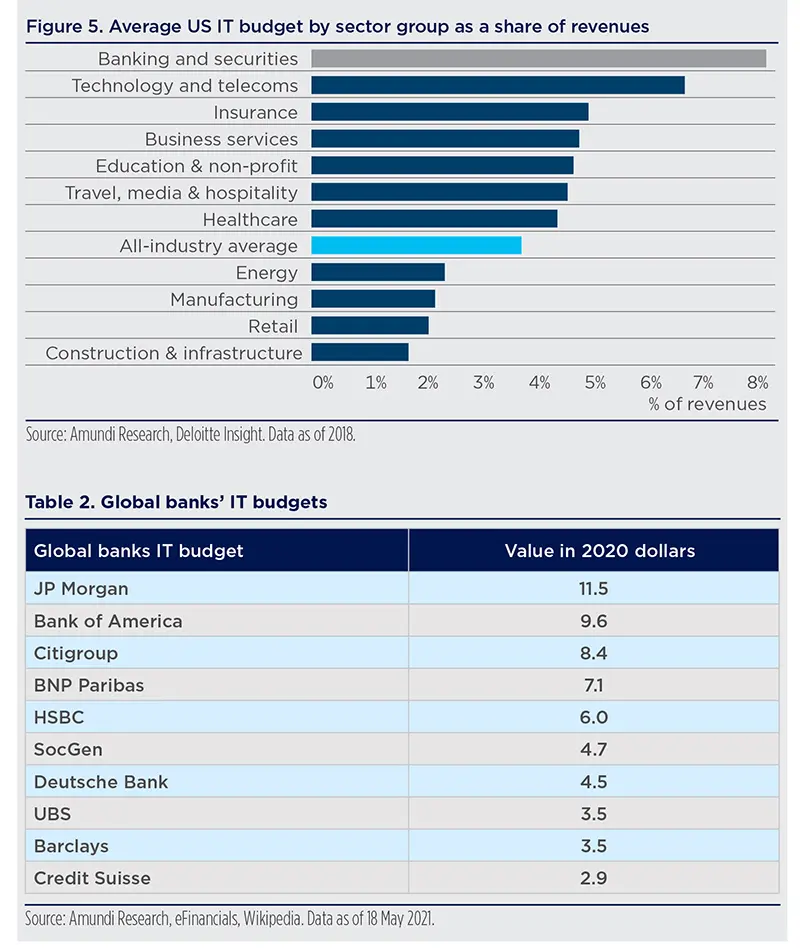

Digital per se does more good than bad…The impact of technology is mixed: it helps banks to offer a better service but at the same time allows more competition and lowers barriers to entry for fintech players. Digital solutions, automation and artificial intelligence improve customer experience and provide innovative services. Clients have access to services when and how they want them, with greater price transparency3. Technology increases competition but grows the market at the same time as it allows services that were not possible or too expensive for low-income populations or remote locations, for instance. Robot advisors on financial planning, passive and model-based investing (machine learning) offer cheaper investment solutions and potentially higher margins regarding the existing client base. Investment banks’ market activities have dramatically evolved over the last 20 years, thanks to electronic trading platforms, pre- and post-trade reconciliations, and checks to address regulatory constraints and rules of exchanges. Moreover, greater data collection, data storage and analysis capabilities lead to more granular market segmentation and, theoretically, allow banks to customise their services at a cheaper cost. Automation helps with the leveraging of human expertise towards high-valueadded tasks rather than just basic administrative functions, enhancing efficiency and security, which leads to an increase in productivity. Teleworking has become the norm, which will dramatically change the geographical breakdown of banking functions and lower costs. Efficiency gains, office space optimisation and reduced operational costs are direct consequences of this accelerated digital transition. … but requires a change in operating modelsTo get the full benefit of the digital revolution, banks have to invest in new infrastructures (fewer buildings, more networks), different skills and talents, and change their operating models. The overall labour and asset structures have to evolve in order to better fit this new framework. Most large banks’ strategic plans are actually built around this and it is a misconception that large bank managements are in denial with regard to the changing needs. Indeed, banking is the largest non-tech sector in terms of IT investments globally.It is in the implementation of these transformational plans that big banks in particular are struggling. According to Gartner, worldwide banking and securities IT spending will reach $550bn this year4. On average, 20% of banks’ operating costs are IT-related. The IT budgets of US banks, for instance, equal nearly 8% of their revenue (see figure 5). However, a significant part of the IT budget is designed to catch up rather than run ahead, and is weighed down by system maintenance or regulatory-related upgrades.

|

What will the competitive landscape look like post the Covid-19 crisis?

New and large entrants

By lowering barriers to entry, digital brings new entrants. Fintechs have so far addressed the easy-to-disrupt part of the financial chain by using cheaper, faster and sometimes safer infrastructure in segments like payment, credit scoring and loans, or stock trading. Banking as a Service (BaaS) opened up a new era of innovation and allowed fintechs to operate in single or multiple banking services. However, the real competition will come from larger organisations, such as Big Tech, such as Apple Pay, Google Plex5, or digital platforms, like Alibaba, Amazon or Facebook. These native digital businesses will compete regarding the core business of banks with an end-to-end service using cryptocurrencies or ‘stable coins’. They benefit from their scale, global reach, huge IT budgets and innovation skills, and direct access to customers’ information and behaviour.

Native digital businesses will compete regarding the core business of banks with an end-to-end service using cryptocurrencies or ‘stable coins'.

Millennials and Generation Z -- which now constitute the bulk of the addressable market -- mainly use online or mobile banking services and therefore can be easily migrated to online platforms. In a way, banking disappears as a standalone service and becomes part of the digital lifestyle under leading brands and platforms such as Google or Apple. If the tech sector’s ‘winner takes all’ principle were to be applied to banking services in a digital world, we could expect to see very large market shares among a limited number of players. Ant Group with Ant Financial and Alipay is a perfect example of a commercial e-platform that became the largest payment platform and money market fund in the world in a couple of years.

Shadow banking is growing due to low interest rates

Banks also face fierce competition from other financial institutions regarding their core business. Low or negative bond yields in Europe incentivise asset managers to compete with banks on lending. Banks and asset managers more often participate in the same deals, like private loans to corporates. Funds are now involved in primary credit lines. Asset managers are looking for higher yields for their end-clients by disintermediating banks and leveraging their credit analytical skills to lend money to corporates via their funds. Insurance companies are offering banking services and savings product to their clients. Peer-to-peer lending bypasses banks in short-term funding. Overall non-bank financial intermediation is growing faster than total financial assets, according to the FSB6, and stays largely out of Basel III scope.

Emerging champions

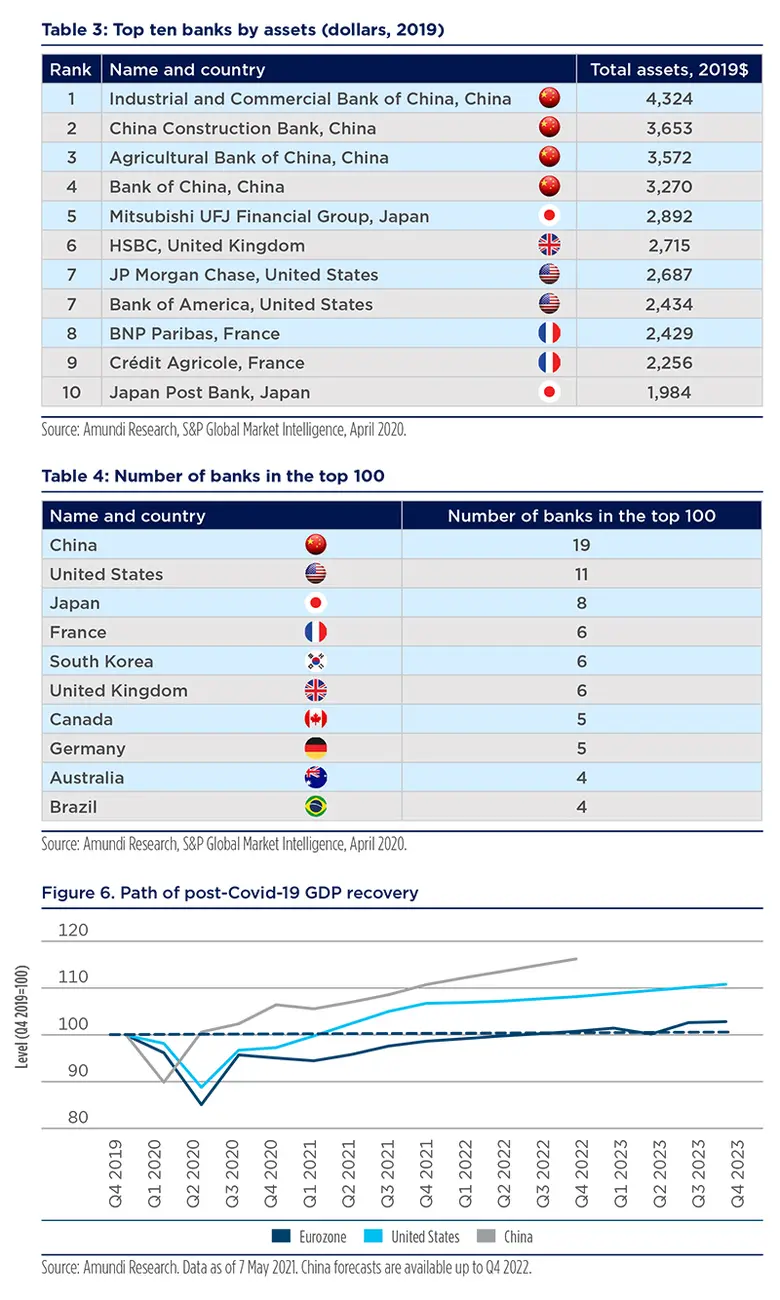

The national champions of emerging economies are reaching the global players’ market. Chinese banks in particular are changing the competitive landscape. At end-2020, five of the ten largest banks based on assets were Chinese. Chinese banks that were mainly focusing on their national market are now lending outside China and promoting the RMB as a transaction and reserve currency. Northern Asia is emerging earlier and stronger from the Covid-19 crisis than any other region. Even if the US and Europe are catching up, the wealth differential will impact the relative game in the banking sector.

The national champions of emerging economies are reaching the global players’ market. Chinese banks in particular are changing the competitive landscape.

Traditional banking will face renewed triple competition from Big Tech, shadow banking and national champions of emerging markets.

| Point 3: Traditional banking will face renewed triple competition from Big Tech, shadow banking and national champions of emerging markets. |

Big is no longer the solution to all strategic challenges

A big asset base with low returns and rising costs linked to regulation and platform upgrade is a competitive disadvantage. Once the best way to ensure strategic strength, multiple balance sheets and global exposures are sources of risk, incremental costs and divert management focus from innovation and growth. Complex global organisations are struggling to adjust quickly to the new competitive landscape described above and to address local and ever-evolving regulations. Therefore, M&A is not the simple solution to strategic issues despite cost synergies in a low valuation environment. As Deloitte banking experts highlight, “Banks may need a new set of tools, expertise, and processes to create a new M&A playbook that will withstand the post pandemic realities”7.

Scale matters more than size and therefore segment leaders have a better chance of succeeding than universal banking players.

Retail banks more than any other financial institutions still maintain large infrastructures, including distribution networks to service households, administrations and corporates where they are located. This is de facto a public service and a public infrastructure that provide financial services and funding to the economy. Yet, the running costs are high, from real estate management to security. Moreover, a large segment of clients, particularly the younger cohort, is not visiting the bank branch and extensively uses online banking. The Covid-19-related emergency procedures allowing account opening and loan granting without a face-to-face meeting have shown that bank advisors might not need such heavy physical networks to do their day-to-day jobs. Offices might only be used for important client meetings.

Regulation has resulted in additional administrative costs throughout the life of the banking relationship. This information must be updated regularly and securely stored while usage is restricted. Open Banking regulation (2018) allows for the sharing of a user’s data and provides better targeted services (alongside GDPR). These data have already been there for a long time, but banks were not doing much with it.

Scale matters more than size

Size is not a key competitive edge anymore: it is actually an issue in traditional banking; small and nimble is an edge. However, ultra-low interest rates are squeezing margins resulting in low return on assets or safe investment products, meaning that it’s more difficult to maintain fees. Scale is needed for services that support traditional banking, i.e., custody, asset management, fund administration and investment banking. There is therefore a paradox within large organisations which need scale to be profitable on their support function but small regarding the end-client-facing part.

|

Point 4: Scale matters more than size and therefore segment leaders have a better chance of succeeding than universal banking players. Point 5: If the tech principle of ‘winner takes all’ is applied to the banking sector, very large global players should emerge regarding several segments or subsets of banking activities. |

If the tech principle of ‘winner takes all’ is applied to the banking sector, very large global players should emerge regarding several segments or subsets of banking activities.

The utilities temptationOne possibility for large banks, which are considered as systemic by regulators, is to become financial utilities, i.e., corporates with regulated returns designed to build and maintain financial infrastructures regarding a defined economic zone. They would be granted a concession with service requirements and pre-determined profit ranges. Balance sheets would become a commodity. Part of the financial industry is already heading towards this model of regulated returns. In fact, the concept of Return on Risk Weighted Assets is similar to the Return on a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) used by electricity, gas or water service providers. The shareholder benefit is supposedly lower and manageable risks should lead to more predictable profits. This would also allow governments to support the transition to digital with long-term investment planning and lower social impacts. However, there are at least three significant hurdles to the utility model: (1) private shareholders need to receive predictable dividends regardless of the economic cycle; (2) regulatory arbitrage becomes a source of profit; and (3) external competition and innovation have to act as constraints to protect the most regulated businesses. All three have proven to be issues during the Covid crisis. The ECB decision to ban bank dividend payments in 2020 on 2019 profits and to cap them in 2021 has de facto broken the commitment to shareholders. Until the European Banking Union is complete, banks will be incentivised to operate with different balance sheets in different jurisdictions. Lastly, fintech innovations and external competition will eventually find their way in since fully dematerialised services are not easy to constrain. So, the utility temptation is not an obvious choice in big market, such as the EU or the United States. |

Why should we still have banks in a post-Covid-19 world?

Digitalisation would have happened with or without the Covid-19 crisis. Price transparency and competition would have lowered returns with or without ultra-low bond yields. Why should we be concerned about banks if they are supposed to disappear as inefficient archaic institutions unable to thrive in an increasingly digital world? Why not move straight away to a fully decentralised model where peer-to-peer lending is the norm and open markets match offers and the demand of financing?

One could argue that, in Europe in particular, banks are a legacy of the past and should be dismantled carefully. The sector, with a large number of direct and indirect jobs, has to be maintained for social reasons, and then there is the economic culture which links banks and their customers. In that case, why are there banks everywhere in the world, including the most advanced economies? Why do emerging economies need to create bigger banks as they grow?

Banks have a specific economic role. They provide three main services -- deposits, payments and credit -- and have three main purposes: the safekeeping of assets, checking information (avoid moral hazard) and money creation.

Banks’ ‘magical’ powers…

The reason is that banks have a specific economic role. They provide three main services -- deposits, payments and credit -- and have three main purposes: the safekeeping of assets, checking information (avoid moral hazard) and money creation8. While safekeeping of assets and information checking can ultimately be outsourced to third parties, money creation is a prerogative of banks9. With or without a central bank, with or without financial markets, this purpose can only be fulfilled by organisations called banks. Since money creation is the liability of assets and requires accurate information as to for whom and for what money is created, the three purposes are ultimately linked10.

The safekeeping of client assets, the gathering and protecting of client information, and the creation of money for the benefit of the economy without financing criminal activities are big challenges.

… need to stay in safe hands…

The safekeeping of client assets, the gathering and protecting of client information, and the creation of money for the benefit of the economy without financing criminal activities are big challenges. Regular breaches of large digital platforms or social networks, leading to millions of credit card numbers and large amounts of client information being stolen, remind us of how difficult it is to protect client information and keep assets safe. Banks are particularly vulnerable to cyber-attacks given the large number of interactions with external entities, such as customers and vendors. But vaults and papers were not more secured than digital systems: indeed, they had their own weaknesses, starting with the loss of a key.

The idea that banks are transforming short-term capital or savings into long-term funding is inaccurate, as most of the money we use has actually been created by banks through credit. Asset managers are doing the capital transformation, not banks. Banks have the monopoly on money creation and the ‘magical’ power that goes with that. They provide the money we need today for tomorrow’s wealth; they are like time machines pointing to the future. That’s one of the reasons why Big Tech or fintechs successfully creating their own money would be the ultimate disruption.

… if states and central banks want to keep control of their own fates

Unless states are happy to give away their control regarding banks’ core prerogatives, it is unlikely that Big Tech and fintech will replace them without the banking sector supervision and regulation. The cancellation of Ant Group’s IPO in January 2021 following the Chinese regulator’s request that its consumer finance branch be regulated as a financial institution rather than a technology start-up is a perfect example.

Post Covid-19, advanced economies’ public debt/GDP reached unpresented levels in peace time to finance stimulus plans. A significant part of the issued sovereign bonds is sitting on central banks’ balance sheets as assets, the counterparty of which is the official money. Big Tech multi-trillion EVs with no debt but cash on balance sheets are credible money issuers compared to highly indebted states. Were there be a safer and liquid alternative to official money, the whole financial system could be at risk of a major privatisation. Since states would oppose such a dramatic change, it is unlikely they would allow large-scale digital private money creation and expend banks’ prerogatives to other institutions11.

Client information is digital gold

Early April this year, more than 530mn Facebook users’ personal data (mainly mobile phones numbers and email addresses) have been hacked. Most global digital platforms have had leaks and security breaches, leading to millions of pieces of client information been stolen by cybercriminals. The social network has hundreds of millions of fake accounts. Today, Big Tech isn’t able to protect its most valuable asset, which is client information, and can’t ensure that companies know their customers.

Banks build a close relationship with clients and maintain high levels of information granularity to build trust, limit risks and fulfil regulatory requirements. Indeed, client information processing, protection and accuracy is one of the key pillars of banks’ activities for their own risk analysis. It is also maintained due to regulatory requirements, the aims of which are to protect the integrity of the financial sector and avoid money laundering or terrorist financing, for instance. In many jurisdictions, banks have a duty to provide this information at the request of regulators or investigators, although it is private data.

Since states would oppose such a dramatic change, it is unlikely they would allow large-scale digital private money creation and expend banks’ prerogatives to other institutions.

We can think about this data collection as a mean to contrast the addressable population and the market. It brings intimacy with the client, accuracy regarding a situation, and a better understanding of behaviours and risks which is far more pronounced than with social media or classic digital services. This is actually one aspect of the fight between the PBoC and Jack Ma’s Ant Group, which owns key information on the the creditworthiness of more than 500 million Chinese people through its two consumer-lending products, Huabei (credit card) and Jiebei (small unsecured loans).

Among the reasons why there are very few global players in the consumer credit segment is the fact that it is a local business which requires good data with limited scale effect.

Although this information collection can be done by third-party specialised firms, it is more efficient to ask banks to do it since they need similar data for their own business. Among the reasons why there are very few global players in the consumer credit segment is the fact that it is a local business which requires good data with limited scale effect. A good knowledge of German households and national regulation doesn’t provide an edge regarding the United Kingdom or Japanese consumer credit market. Despite databases, models and scale, a deep understanding of local economic and social situations is key to success in lending12. And, the principle of banks’ secrecy is an important source of trust. Therefore, there are economies of scale and security benefits when banks look after client information. Banks in Europe play a key advisory role with regard to savings, investments and household financial protection. They have a social role on top of their economic duties which shouldn’t be underestimated. Relevant and legitimate advice is often as important as products or prices for wealth management. In that context, robot advisors are powerful tools when combined with personal interactions and a nice way to mix digital and artificial intelligence with a human approach.

ESG is the other revolution

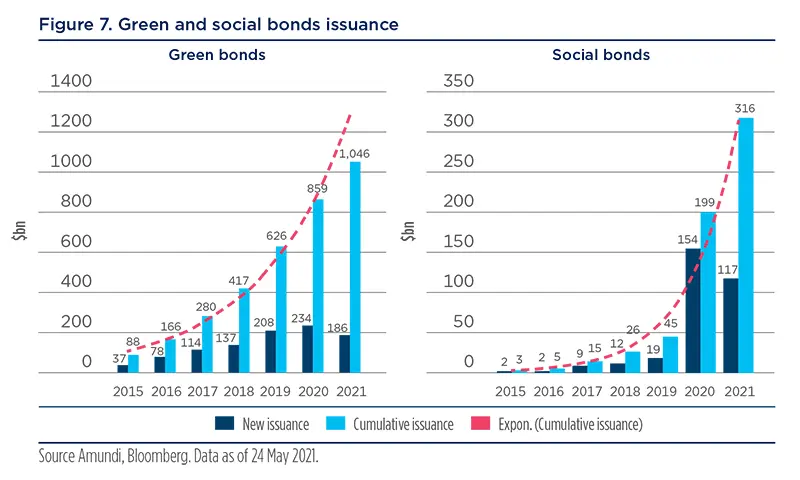

Banks’ positions in the economic architecture mean they are the main (if not the only) conduit of ESG at the global level. The end use of money created, the impact of investments on climate change and social inequality are now of paramount importance for customers, shareholders, stakeholders and regulators. Investment banks and commercial banks with their asset management arms are the main players in the Green bond market.

According to our research, the cumulative issuance of Green bonds has multiplied tenfold since 2015, to $1tn. Social bond issuance moved from $19bn in value in 2019 to $153bn in 2020, and we believe this nascent market will catch up with Green bonds over this decade. Our analysis shows that ESG is a change of paradigm, with significant influence on investor behaviour13. Equity funds with ESG as a core pillar of the investment process are seeing a greater share of inflows and the inclusion of responsible equity options is associated with higher equity allocation. In this context, regulators’ and central banks’ recent decisions to include climate change in their policy are acting as strong support mechanisms. Taken on board, ESG becomes a key competitive edge and an addition to banks’ purposes that cannot be easily challenged by new entrants and technology alone. Big Tech is actually often seen as ESG unfriendly (see energy consumption, lack of product recycling, employee social rights, tax avoidance, etc).

ESG is a change of paradigm, with significant influence on investor behaviour.

Banks are by nature the gatekeepers of the ‘G’ of ESG, not only for big corporates but more importantly regarding small local businesses. Accounting rules and adequate decision-making processes are de facto cross-checked by banks in the lending process which has a governance role in credit creation. They also play a key role in the ‘S’, as they ensure access to payment, funding and savings to the broad population and act as an institutional presence in many locations that are at the periphery of decision centres.

|

Point 6: There are at least two reasons why we still need banks in a post-Covid world: they constitute the backbone of official money creation for the right purposes and they protect client digital information and assets. Point 7: Banks are a meaningful conduit of ESG: they enforce good governance, contribute to social linkages, and foster the energy transition. |

There are at least two reasons why we still need banks in a post-Covid-19 world: they constitute the backbone of official money creation for the right purposes and they protect client digital information and assets.

Investment implications: winners and losers in a post-Covid-19 world

Credit cards were big disruptors when they appeared in the early 1960s with the first Bank of Americard. ATMs disrupted banking services in the ‘70s and most ‘guiche’ to withdraw money disappeared as well as the jobs related to these tasks14. But banks did not disappear with credit cards or ATMs. There are dozens of similar examples in the history of banking which show that technological progress transform the sector. The digital revolution which Covid-19 is accelerating and is pushing banks to change once again. Banks’ operating models, infrastructure, employees’ skills and even locations have to be redefined as services are now centred on the client, not the bank. But this is just another step in the ever-changing banking business. Therefore, the issue is more which banks (i.e., which activities and geographies) will be able to ride the digital wave and become leaders in the post-Covid world rather than whether banking will survive as an industry.

It is not so much banking as a type of business per se that is threatened by the digital revolution, but corporate structures, which are late in transforming themselves into agile organisations able to thrive in a digital world. Rather than the new digital paradigm itself, it is the legacy of the past and the size of these organisations which make them look like dinosaurs in a changing environment. Fintech are mostly smaller, more focused and nimble technology-savvy organisations that are able to operate efficiently in the new framework which they contributed to building. As investors, we can define some criteria on what could be winning and losing banking models going forward.

It is not so much banking as a type of business per se that is threatened by the digital revolution, but corporate structures, which are late in transforming themselves into agile organisations able to thrive in a digital world.

Table 5. Winning and losing banking models

| Scalable digital platforms |

As digital becomes the core backbone of banking, the rule of digital competition and concentration, i.e., ‘winners take all’, should apply to the sector as well. Big is not the solution, but scalability is a prerequisite for success in the digital world. Efficient and innovative digital banking service providers will take significant market share probably beyond what we’ve seen in recent history. It means that digital banking platforms could have several hundreds of millions of customers. This is one of the biggest challenges for regulators face with much larger and therefore systemic organisations than before. |

| Global platforms or super-niche players |

Winning platforms will be those that are able to offer or give access to a broad range of services via mobile and online banking, so the client doesn’t see the need to go elsewhere. But niche players will also have a winning position since they will be able to either offer greater services for cheaper costs or simply offer services that require bespoke content or actions. This applies mainly to wealth management, private banking and investment banking. |

| M&A to acquire technology and digital customers rather than cut costs |

As is the case for Big Tech, which has been acquiring fast-growing firms to protect and enhance core businesses (e.g., Facebook acquiring WhatsApp), banks will acquire fintechs and neobanks to maintain their competitive edge and increase the number of users on their digital platforms. M&A as a cost-cutting strategy to protect traditional banking might not be the right choice. |

| Cross-selling or open platform |

As they are already doing today, banks will leverage their client relationships and information to cross-sell. Digital offers inequivalent realtime information on clients’ needs and provides the data usage is allowed, and makes cross selling easier. Wining platforms will be built around customer information and cross-selling capabilities, and should be open in order to offer a broad range of products at competitive prices. |

| ESG as the core service and product offering |

Offering ESG savings and investments products is key. Yet, showing the way banks are using deposits, capital and money creation is critical too. In this context, full transparency is a prerequisite starting with pricing but also end-toend usage of funding and design. |

Source: Amundi as of 20 May 2021.

Digital services, automation and artificial intelligence are great technologies, but they are only tools and systems. Post-Covid-19, changes to operating models are unlikely to alter the main purpose of banking. In fact, technology is not the problem but part of the solution for banks. It offers more efficiency, more security, and, eventually, higher trust. Fides is a critical, symmetrical and intangible substance of the bank and customer relationship. “Banking without trust, is like prayer without faith”15.

Post-Covid-19, changes to operating models are unlikely to alter the main purpose of banking. In fact, technology is not the problem but part of the solution for banks.

___________________________________________

1Source: Refinitiv consensus-weighted average, June 2021.

2 See BIS Quarterly Review, September 2020

3 2021 banking and capital markets outlook: Strengthening resilience, accelerating transformation, Deloitte Insight Dec 2020.

4 Gartner Forecasts Worldwide Banking and Securities IT Spending, August 2020.

5 Google Plex, launched in January 2021, is an upgrade of Google Pay which allows app users to open and manage bank accounts.

6 The Financial Stability Board (FSB) global monitoring on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation (NBFI) shows that in 2019 the NBFI sector gain outpaced that of banks and represents at the global level $200tn, or 50% of global financial assets. The narrow measure of NBFI grew by 11% in 2019. See FSB report 16th December 2020. Shadow banking is de facto dumping if the true cost of regulation, capital and liquidity is not included in the funding cost. Banks’ current accounts liquidity is real whereas asset managers’ fund daily liquidity on most funds is more virtual, as it would sometimes takes several days to liquidate the entire portfolio. Asset managers act on behalf of their clients, not in proprietary positions. Therefore, they benefit from low regulated capital requirements despite the transformation risk of using short-term liabilities to finance long-term investments. Hence, the recent focus of regulators on asset management and private equity firms

7 2021 banking and capital markets outlook: Strengthening resilience, accelerating transformation, Deloitte Insight Dec 2020.

8 “The Purpose of Banking”, Anjan V. Thakor, 2019 and “Banks at the heart of the matter” by Jeanne Gobat, International Monetary Fund.

9 Despite their proponents cryptocurrencies are not money since they do not fulfill the three characteristics of money (as a unit of account, a store of value and a medium of exchange).

10Banks as organisations can have a higher purpose which is usually a function of the region in which they operate or the clients they serve. For instance, Credit Agricole Group’s higher purpose is to “Act every day in the interest of our customers and society” with a clear social and ‘green’ focus. HSBC has a different higher purpose, which is ”Opening up a world of opportunity”. It is linked to HSBC’s unique position as a bridge between Asia and Europe.

11See Philippe Brassac (Crédit Agricole CEO and President of the French Banking Association), “Money is a state prerogative which should be managed carefully managed in quantity, quality and security”, Journal du Dimanche, 29 March 2021.

12“Credit ratings cannot replace relationships, leverage is no substitute for judgment, and the pursuit of profit should not come at the expense of prudence”. Anjan V Thakor, 2019.

13Responsible investing and stock allocation, M Briere & S Ramelli, Working paper, Amundi Research, 13 January 2021.

14 “Fintech and banking, what we do know?” Anjan V Thakor, Journal of Financial Intermediation, July 2019.

15The Purpose of Banking, Transforming Banking for Stability and Economic Growth, Anjan V Thakor (2019).

Definitions

- AT1: Additional Tier 1 capital instruments are continuous/perpetual, in that there is no fixed maturity including, preferred shares and high contingent convertible securities. Contingent convertible securities (often referred to as CoCos) are a major component of AT1 and their structure is shaped by their primary purpose as a readily available source of capital for a firm in times of crisis.

- Basis points: One basis point is a unit of measure equal to one one-hundredth of one percentage point (0.01%).

- CoCo bond: A contingent convertible bond is a fixed-income instrument that is convertible into equity if a pre-specified trigger event occurs.

- Common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio: CET1 comprises a bank’s core capital and includes common shares, stock surpluses resulting from the issue of common shares, retained earnings, common shares issued by subsidiaries and held by third parties, and accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI).

- Tier 1 ratio: The tier 1 capital ratio measures a bank’s core equity capital against its total risk-weighted assets.