Opportunities in a reconfigured world

- The global economic outlook is benign as monetary policymakers have curbed high inflation without triggering a recession. Abating price pressures will allow major central banks to cut rates further but the easing cycle will end well before policy rates reach pre-pandemic lows.

- Geopolitics and national policy choices are paving the way for more fragmentation, with the United States pursuing geostrategic competition and the European Union focusing more on strategic autonomy. Drilling into sectors that will benefit from big trends is important given this backdrop and valuations.

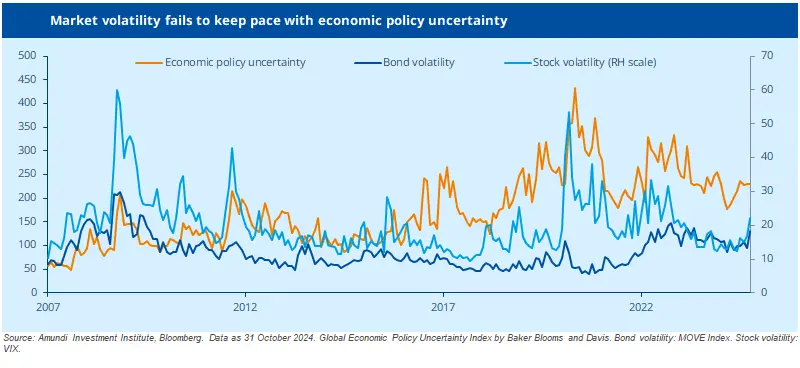

- Anomalies, such as low equity market volatility at a time of uncertainty, are becoming marked and may not last. A reversal of such phenomena could see assets like inflation-linked debt and gold find more favour.

Halfway through the decade, new forces are reconfiguring the post-pandemic global economy. The big shocks that hit labour markets, supply chains, and energy prices in the past five years have largely worked their way through the system. But geopolitics and national policy choices are creating a more fragmented world that may bring new surprises.

Monetary policymakers have so far done a good job of curbing high inflation without slamming the brakes on growth. The world economic outlook is therefore benign, with a slowdown in US activity unlikely to turn into recession. Meanwhile, global price pressures are expected to ease further. US policy shifts pose some upside risks, but ultimately, no one has an interest in seeing inflation surge.

This will allow major central banks to keep cutting interest rates and financial markets to build on the gains of the past year. Earnings prospects offer opportunities for the rally in equities to extend beyond US mega-caps. Such moves will be further fuelled if US campaign promises of deregulation and corporate tax cuts are fulfilled.

But there are a couple of caveats. First, investors have already anticipated a lot of good news. The best opportunities will therefore be found by drilling into sectors that will benefit from the big themes that will dominate the coming years. These include demographic trends, shifts in where global manufacturing takes place and who dominates such production, as well as the effects of climate change and the cost of energy transition or the re-routing of global supply chains.

Second, the monetary easing cycle on which most developed economies have embarked will end well before policy rates reach pre-pandemic lows. This is due to shifts in key growth drivers, which are boosting potential growth in countries like the US and India. Also, the global economy may be subject to more shocks from geopolitics, technological innovation, trade, and climate change. Central banks may therefore have to respond more quickly and forcefully to such shocks than in the past if they are to keep inflation expectations anchored.

Meanwhile, anomalies - such as the past year’s low equity volatility in a time of high uncertainty, or the resilience of the US consumer in the face of the sharpest tightening cycle in decades - are becoming more marked and may not last. A reversal of such phenomena could see fixed-income, inflation-linked debt and gold find more favour.

Political choices may also stoke demand for safe havens like gold. While 2024 was the year of the ballot box, those who were elected must now confront long-deferred problems in order to avoid more serious difficulties later in the decade.

Spotting the opportunities created by policy choices and geopolitical shifts will be as important as safeguarding portfolios against some of the risks they entail.

For example, incoming US President Trump faces record levels of debt, big structural deficits, and rising interest payments. Pre-election pledges mean debt will keep piling up. Investors are likely to keep faith with Treasuries as long as the US economy keeps growing but the fiscal outlook points to higher fixed-income volatility. Market swings may be even more pronounced given sources of demand for US debt are in flux, with the Federal Reserve, commercial banks and investors in China and Japan absorbing a smaller proportion of overall issuance.

Washington is also likely to pursue geostrategic competition. This involves maintaining its lead in technology such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing and chips. It will also view certain manufacturing activities as a matter of national security. The United States will therefore grow more inward looking.

The ripple effects will be felt across the Atlantic and encourage European politicians to focus on strategic autonomy. They will also have to tackle the root causes of their region’s widening productivity and investment gap with the United States. Mario Draghi’s report contained a useful roadmap of how to do this but implementation will require more political commitment than is evident at the moment. This is especially true for some ideas, such as issuing common EU debt for specific purposes – a necessary step for radical change.

This is not a constraint for other regions. Chinese policymakers have scope to deploy more fiscal stimulus as they steer the economy on a more sustainable growth path. But the size, timing, and focus of such spending will determine its effectiveness. Meanwhile, Gulf states will ramp up investment in infrastructure that will benefit more of their citizens – a development that could create demand for a range of commodities.

Spotting the opportunities created by all these policy choices and geopolitical shifts will be as important as safeguarding portfolios against some of the risks they entail. In a world of anomalies, there are plenty of bright spots.