Summary

Key takeaways

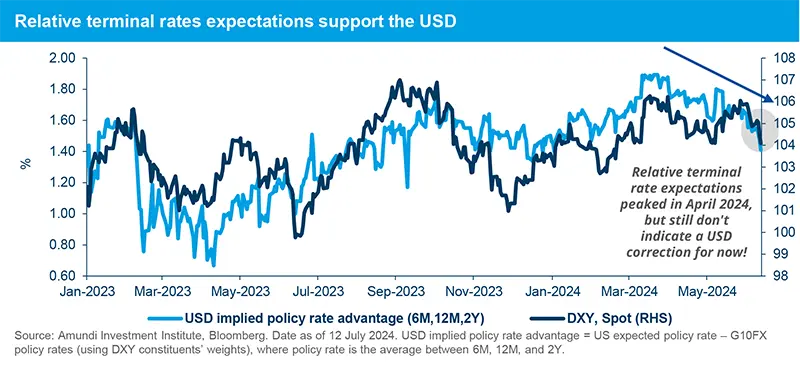

- The divergence of Central Bank policy rates is unlikely to significantly impact exchange rates, as other core currencies are not weak relative to recent history and market expectations of terminal rates in Europe are similar to those in the US.

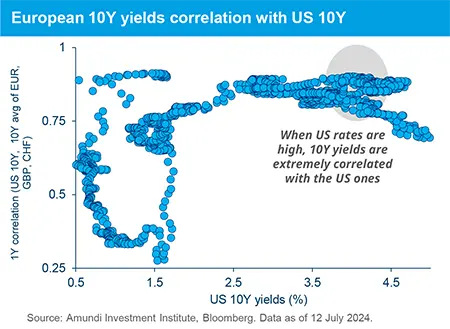

- Global financial conditions are strongly influenced by US longend yields, and there is a risk of the term premium rising if US deficit and debt projections deteriorate.

- Although not in our baseline scenario, an energy supply and price shock would weaken European exchange rates and rapidly transmit to domestic inflation.

Central Bank policy rates can diverge

The pace of disinflation in most advanced economies is following a similar path, albeit with differences in sticky components. Central bank policy rates are unlikely to diverge significantly (our baseline), but this does not rule out the ECB and the BoE cutting rates faster than the Fed, especially given their weaker growth outlook. The impact of this scenario would be steeper yield curves in the Eurozone and the UK, but not substantially weaker exchange rates, as some fear. A bigger risk to European exchange rates stems from (unanticipated) energy price shocks rather than lower relative interest rates. We explore why.

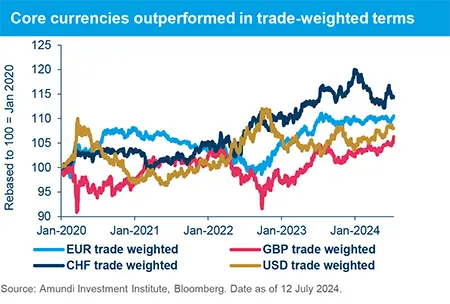

The US dollar has been exceptionally strong, but other core currencies (except the Yen) have also been strong in trade-weighted terms.

| The global macro backdrop – inflation scares, geopolitical tensions and recession worries – together with US economic resilience, have supported the dollar versus core currencies, but the latter are not weak relative to recent history. Moreover, the difference in market expectations of terminal rates in Europe are now substantially higher than before the pandemic, and not materially different from expected US terminal rates. This should limit any sustained weakness in European exchange rates. |

|

Fears about exchange rate depreciation are overdone

When Central Bank policy rates diverge, there are typically two main risks that may make rate cuts unsustainable: 1) exchange rate depreciation and 2) inflation pass-through from exchange rate depreciation. While monetary policy rate differentials matter, both risk factors seem less of a worry in this cycle. First, exchange rate volatility has been unusually low, despite the Fed becoming incrementally hawkish in 2024 relative to most other Central Banks. US disinflation has allowed the Fed to maintain its bias towards cuts, which has contained both the distribution of expected inflation and forward US rates.

Second, the inflation pass-through of exchange rate depreciation is estimated to be relatively low (around 0.10 percentage points for a 1 percentage exchange rate point depreciation in the Euro Area). A related third factor is that the ECB and the BoE are not easing their restrictive policy stances in response to a growth shock. Such support for growth would, over time, strengthen their exchange rates. Fourth, the absolute level of yields matters. Euro and UK terminal rates are expected to be substantially higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Policy rate divergence would, however, imply steeper yield curves in Europe

Global financial conditions at the long end are strongly influenced by US long-end yields (primarily reflecting the size of US markets), particularly since the pandemic.

| Thus far, global markets have benefitted from the absence of any substantial term premium in the US because policy rates have been expected to fall (with inflation) and the US is continuing to attract foreign capital. But there is a significant risk that the term premium could rise over the medium term, possibly by a significant amount, if the US deficit and debt projections continue to deteriorate. This is the real risk that European Central Banks will have to manage: a much steeper yield curve than would materialise from going a little faster with rate cuts. Moreover, the absolute level of yields also matters. |

|

With the end of QE and the era of negative-yielding government debt outside the US, higher US yield levels will likely have larger spillovers. Any substantial and sharp rise in the US term premium, perhaps due to market concerns about debt issuance and fiscal paralysis in the US, could in turn also have strong FX effects. Here we would worry about low-yielding currencies, such as the Yen.

Although it’s not our baseline, another energy shock would also impact exchange rates. Our baseline sees oil and gas prices on a gradual and slow downward trajectory. But an energy supply and price shock would weaken European exchange rates and rapidly transmit to domestic inflation. As most commodities are priced in US Dollars, the resilience of trade-weighted exchange rates would not help contain imported inflation.