Summary

The concept of strategic sovereignty goes far beyond the issues of security and defence. It also assumes relative self-sufficiency, and the ability to impose one’ standards and to create global leaders in tomorrow’s ecosystems. This political objective must be founded on economic reality and will first require new investment momentum in Europe.

The issue of European strategic sovereignty has been thrust back into the centre of public debate by the public health crisis. And as France assumes the rotating presidency of the European Union, President Emmanuel Macron has once again made it a political issue. And yet, it is a hard concept to grasp, as it takes in several realities and goes well beyond the issues of security and defence. Strategic sovereignty is understood to be the possibility of broadening the range of what is possible while remaining consistent with one’s own objectives; and the European Union is still far from achieving that.

Reducing strong external dependencies

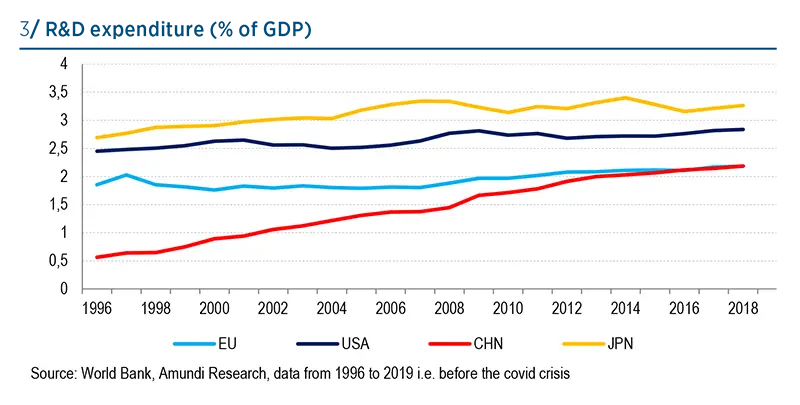

The sudden halt in imports during the lockdowns reminded us that sovereignty is, first and foremost, a matter of securing the supply of essential goods. There are almost 140 products for which Europe depends almost entirely on non-European suppliers. This list includes raw materials and fossil fuels, as well as electronic components and medicines. Oil dependence will be reduced by the energy transition, but the transition will entail just as much dependence on metals, rare earths and photovoltaic cells1. China currently accounts for more than half of imports, by value, of products for which the EU’s external dependence is very high. But the EU is also closely dependent on India for pharmaceutical components, and it is almost completely dependent on Taiwan for advanced semiconductors.

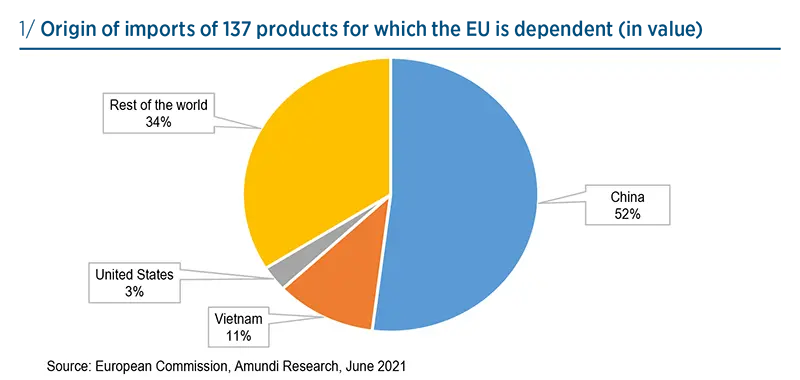

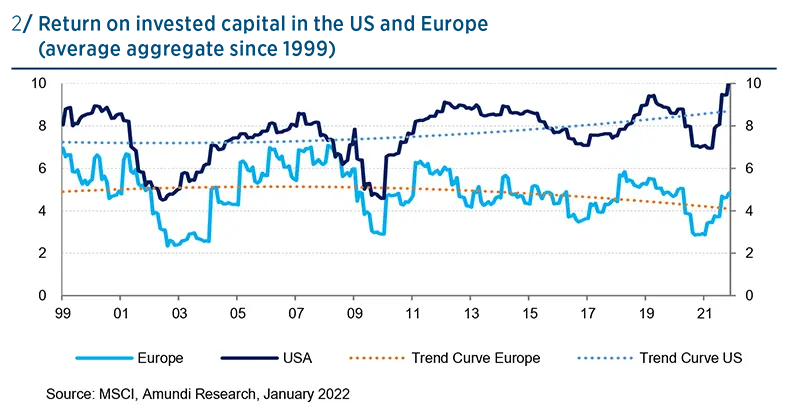

Geological constraints are hard to get around, but production of industrial goods in Europe, combined with greater diversification of suppliers, would help make the continent more autonomous. That being said, it will require billions of euros in investment over about a decade2. And European companies’ return on invested capital has fallen constantly since the financial crisis and has diverged dangerously from that of their US peers3. Such investments will require creating the right regulatory environment4, steering savings and institutional investment towards the long term, and ensuring that returns on investments are consistently higher than the cost of capital.

Strategic sovereignty requires first a lower dependency on critical good

Being able to set the rules of the game

The second aspect of strategic sovereignty is autonomy of standards. If, during peacetime, war is commercial in nature, then standards and regulations are its weapons of choice. Setting and imposing these standards is a hallmark of sovereignty. Incidentally, we have seen that most of the conflicts between China and the United States are engaged over standards, with the US accusing China of not applying the rules that it have established very broadly over the past 30 years, while China asserts its legitimate right to impose its own standards. The European Union, whose ability to churn out standards is at times controversial, is at least able to impose its own standards, as it showed with the GDPR5.

The green taxonomy that the EU is now finalising is a major strategic importance in the context of the energy transition. Europe will ensure its autonomy if it manages to impose its own rules, which will direct the 200 to 300 billion euros in investment needed each year to ensure this transition on the continent.

Europe’s return on capital is falling

Giving birth (or rebirth) to global leaders

A third avenue of strategic sovereignty is creating or strengthening European leaders in segments that will ensure sovereignty of tomorrow. This doesn’t just involve sectors but entire value chains and ecosystems that will lead to the development of new products and services. Some examples of this are artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, e-commerce platforms, the cloud, the Internet of things, green mobility, hydrogen, space and advanced medical equipment. These segments offer returns on invested capital that are higher than the European average of the past 10 years, but developing them will require greater financial integration in Europe6.

To become a political reality, European strategic sovereignty must be an investment opportunity. This will, in turn, require that returns on investment are attractive and at least equal to those on offer in the world’s other major regions. Public funds will point the way but won’t be enough to meet all equity capital needs. Private investment and long-term savings will also be needed, in the form of thematic listed or private equity or debt funds that align the goals of governments, companies, and investors.