Summary

Most people are prone to investment biases, do not diversify enough and fail to rebalance their portfolios. Robo-advisors have helped retail investors in this task. We have shown that improved diversification and rebalancing greatly enhances their performance.

The advancement of financial technology (FinTech) has reshaped the way people access financial services, from the introduction of internet-based trading (1990s) to the growing importance of mobile apps, robo-advisors and social media. These digital innovations have removed many of the barriers preventing retail investors from participating in financial markets1 and this has contributed to retail investors’ appetite for investment. The recent pandemic also added to this growing appetite, with individuals suddenly left with extra time and cash. A new class of retail investors emerged, with different types of motivation and behaviour.

Strong tailwinds

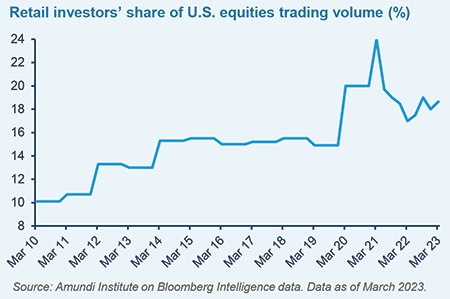

In 2010, retail trading accounted for less than 10% of the total stock market trading volume. Now, however, it constitutes more than 18% of trading in the U.S. (see figure below).

In 2020, about 5 million retail brokerage accounts were opened (approx. 15% of U.S. equity investors)2 while more than 6 million Americans downloaded a trading app in January 2021.3 Similar trends in retail trading can be observed in Europe, Asia and Africa.4 Being optimistic about their prospects, these new retail investors participate in investment forums, trade on apps and invest in a wide range of different asset classes and markets (e.g. crowdfunding, cryptos).5 Unfortunately, they are also frequently financial novices. How is retail investing evolving and should financial institutions adapt to serve the needs of this new type of customer?

In this paper, we discuss four emerging trends in retail investors’ behaviour related to technological change. These trends include the increasing use of mobile apps, robo-advisors and social media platforms as well as the rising interest in crypto investment. New technologies are offering easier access to investments at lower costs, which is raising retail investors’ interest. Some digital services (e.g. trading apps, social media), however, have an unexpected negative impact on behaviour, such as increasing turnover and amplifying biases (e.g. return chasing, disposition effect).6 Other technologies, like robo-advisors, have greatly helped retail investors by allowing them to set investment goals, define a strategic allocation, rebalance and, ultimately, reduce investment mistakes. We conclude by discussing how financial players could adapt their products and services to cope with these new behaviours, foster sound investment practices and answer retail investors’ needs for financial education.

Emerging trends in retail investors’ behaviour

A widespread adoption has led to a boom in the development of mobile trading apps. Investors can trade at any time and from all locations.

Retail investors are active on finance related to social media as users or creators of content, discussing news events, sharing investment research and debating investment strategies.

Using automated procedures, ranging from simple algorithms to complex systems, these advisors recommend how to allocate funds across different types of assets or funds.

Technologies have made investment more attractive to retail investors but have also led to some risky investment behaviours and additional investment biases.

Source: Amundi Institute, June 2023.

Using smartphones to invest: does it make a difference?

Technology is re-defining distribution, wealth management and advice models: the challenge is to provide a seamless experience with the best combination of digital and human.

Since 2000, smartphones have been ranked the most influential consumer technology.7 In 2020, the number of smartphone users worldwide reached 3.6 billion, and an average user spent a quarter of their waking time on their smartphone every day.8 This widespread adoption has led to a boom in the development of mobile trading apps which allow investors to access market information and trade at any time and from all locations. Today, more than 25 million people in the U.S. are using smartphones to trade securities.9 What is the impact of retail investors’ adoption of financial apps on their investment behaviour?

- A large impact on risk-taking: recent research studied the transactions on mobile apps of 15,000 clients of two large German retail banks between the years 2010 and 2017.10 After observing the platform used for each trade (e.g. personal computer versus smartphone), it was established that using the app, increased the probability of investing in risky assets (volatile or lottery-type stocks11) by 67% in relative terms compared to non-smartphone trades. Smartphone trading also increased the relative probability of “chasing” returns (i.e. buying assets which rank in the top 10% in terms of past performance) by 71%. The results are not driven by the initial enthusiasm about the new technology and, importantly, do not appear to be short-lived.

- Amplification of investment biases: investment app adoption also seems to amplify cognitive biases, such as self-control problems and overconfidence. Using data from a leading investment adviser in China12, a study showed that after the introduction of a mobile app, investors’ attention and trading volume increased substantially (by 143% and 80% respectively).13 In addition, flows into mutual funds became more volatile and sensitive to short-term (1 week) fund returns and market sentiment. Young investors, who are presumably more prone to self-control problems, showed a greater increase in logins and trading intensity. Furthermore, male investors were more affected than female investors.

What explains the impact of mobile apps on investors? The design of the app itself could play a role. A recent paper outlines how an app’s notifications, such as displaying top movers (similar to those on the Robinhood platform14), affect investors’ trading decisions.15 However, even when the app does not display any specific design compared to the website, retail investors’ behaviour is different. Initially, this was considered to be due to smartphones’ physical attributes, such as their smaller screens, but it was determined that there are no differences in trading via devices with different screen sizes (e.g. iPhones versus iPads). Dissimilarities in behaviour could be explained, however, by varying circumstances (e.g. different hours or conditions) in which investors access the trading apps. For example, a recent study16 outlined that smartphone effects are stronger after hours (after exchange closures), probably as later in the day individuals are more likely to rely on their more intuitive “system 1” thinking. 17 These puzzling effects need further investigation.

Does social media help with making investment decisions?

The social nature of investing: a large body of literature highlights the influence of peers on investment decisions. Schiller (1989) proclaimed that “Investing in speculative assets is a social activity. Investors spend a substantial part of their leisure time discussing and reading about investments, or gossiping about others’ successes or failures in investing.”

In this context, social networks have always had a great influence on investors. The London Stock Exchange started in coffee houses in the 17th century, and social dynamics gave rise to famous bubbles like the South Sea Bubble. However, it is only recently that digital platforms have made social networks much larger. Today, retail investors are increasingly active on finance related social media through creating content, discussing news events, sharing investment research and debating investment strategies.

The development of social trading: the last two decades saw the development of various types of social media in finance. Some platforms (e.g. StockTwits, SeekingAlpha) allow investors to share opinions about securities, without offering trading services while others (e.g. eToro, Skilling, ZuluTrade) combine social media with a trading platform. These platforms are different from the classic platforms because they offer the possibility of so-called “mirror trading” (copy and automatically execute investment strategies of other traders, referred to as “signallers”, or “trade leaders”). Signallers display on their profiles their trading strategies, performances, number of followers and rankings, and are compensated through performance fees while users are charged fees by the trading platforms (e.g. spreads or order costs). This type of trading created a new kind of market by enabling social interaction between signallers and followers.

Do social trading platforms provide value added advice? There is an intense debate on the value of social media recommendations. Some studies suggest that social media spreads stale news18 while others find evidence that certain types of social media can provide investment value.19 Researchers have also found that social trading portfolios (e.g. wikifolios) do not outperform the market, on average, even if the best performing ones earn significant short-term returns.20 In fact, social learning has encouraged riskier trading and hurts performance21. Although followers are likely to select the right signallers22, the latter also tend to replicate the strategies of their competitors. Furthermore, investors do not select signallers based on performance indicators but, instead, are largely influenced by social dynamics, such as the number of followers.23

An amplification of investment biases: research highlights that traders search for mutually beneficial peer-connections when their strategies display attractive performance and they have greater bargaining power. 24 This has a tendency to exacerbate retail investors’ disposition effect, which is strongest among inexperienced traders with the most to gain from forming social connections.

On social media platforms, retail investors also voluntarily place themselves in “echo chambers” (i.e. they selectively expose themselves to confirmatory information). This was clearly highlighted by a study focused on 400,000 users of one of the largest social network for investors, StockTwits.18 33 million posts and 14 million follower-connections were examined. StockTwits users mark their posts as bullish (or bearish), and one can observe who they choose to follow. Self-described “bulls” are 5 times more likely to follow a user with a bullish view of the same stock than self-described “bears”. This selective exposure generates significant differences in the newsfeeds of bulls and bears: over a 50-day period, a bull will see 62 more bullish messages than bears. Furthermore, investors have a greater tendency to seek confirmatory information when they have “skin in the game”. For example, users that have an ongoing trade are three times more likely to follow same-sentiment users, relative to users who are not trading.

The negative impact of upward social comparison: social media exposes investors to upward social comparison, which has a large impact on investment behaviour.4 Investors take more risk and trade more actively, but they also report significantly lower satisfaction with their own performance. This is one of the pitfalls of digital investment platforms offering peer group comparisons.

What is special about crypto investment?

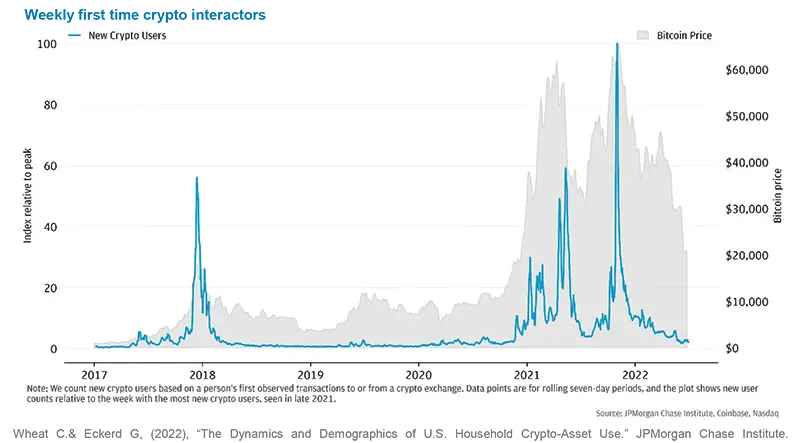

The typical profile of a crypto asset investor: households’ investment in crypto assets rose sharply during the Covid-19 period. As of mid-2022, almost 15% of individuals had made transfers into crypto accounts.25 In the U.S., crypto holders are mostly young males26 with higher incomes, “libertarian” or politically independent.27 In general, these assets represent a small fraction of their financial wealth, despite the fact that almost 20% of surveyed individuals report that they constitute at least 50% of their financial portfolios. Furthermore, crypto holders are usually homeowners who are higher income earners and spenders than non-holders (in particular via credit cards) and twice as likely, when compared to a non-holder, to have gambled.

However, these investors are not a homogeneous group. Those that entered the market early (prior to the 2017 Bitcoin price rise) are more likely than late adopters to be relatively larger spenders, run overdrafts on their checking account and have gambled. They also tend to be more wealthy, financially educated and living in places with a high concentration of managerial occupations.28 In contrast, late adopters are, generally, not only less wealthy but, on average, fare worse due to buying later into upward price trends.

Polarised views: since its inception in 2009, Bitcoin29 has polarised views, from strong support (Elon Musk) to being seen as a vehicle for speculation, or even a poison (Jerome Powell or Warren Buffet) . This difference of opinion is reflected in the general population. One of the main reasons why retail investors buy crypto assets is their belief that their investments will generate high returns27 and diversify traditional portfolios. While many investors view them as offering a store of value and a hedge against inflation, they also are acting on a desire to support the development of this asset class. Conversely, non-holders of crypto assets justify their decisions by a lack of knowledge and a view that these assets are not only too risky, but also do not add much value to their portfolios. When asked about expected returns, crypto holders hold much more optimistic views than those of traditional investors (traditional assets holders and non-holders have, on average, the same return expectations).

Investment behaviours: the share of crypto holders rose sharply between 2021 and 2022 (from 3% to 11%) when Bitcoin prices were rising. However, interestingly, investors were not discouraged by the decline in crypto assets’ valuations that occurred during the “crypto winter”.30 Indeed, the share of people holding crypto assets rose further to 12%. A recent research study31 reveals that owners of large wallets reduced their holdings of Bitcoin in the days after the market turmoil episodes, while smaller holders increased their holdings. The price patterns suggest that larger investors were able to sell their assets to smaller ones before the steep price decline while smaller investors made large lossess.

Crypto holders differ, not only in their demographic characteristics, but also in their investment behaviour in both the crypto and traditional assets classes.32 They are more active traders (9 versus 2 trades per month), and log into their brokerage accounts more often (82 times versus 27 times per month). They also compose their portfolios differently from the average investor: they are significantly more likely to hold single stocks, equity derivatives and warrants.

Technology adoption is a strong determinant of investment. For example, crypto holders are 3 times more likely to have used the mobile-banking or mobile-trading apps offered by their banks. In addition, crypto traders tend to follow momentum strategies, transferring money to crypto accounts when these assets can be significantly higher than recent levels. Furthermore, new investors in this market place are inclined to enter the market when crypto prices are peaking, especially those with lower education. 25

Do robo-advisors add value to investors?

A growing market: robo-advisors are attracting growing interest in the industry. Using automated procedures, ranging from relatively simple algorithms to complex systems built around big data, these advisors recommend how to allocate funds across different types of assets or funds. A client profiling technique is employed to assess an investor's goals and characteristics (i.e. risk aversion, financial knowledge and investment horizon) which are then used to build client portfolios.

In addition to recommending an initial allocation of funds, algorithms can monitor clients’ portfolios and detect deviations from their targeted profiles. Whenever deviations are identified, the clients are alerted or, in the case of “managed accounts”, the portfolios are automatically rebalanced. Portfolios can also be rebalanced to reduce risk or cater for changes in investors’ risk tolerance or investment goals. In the U.S., robots propose to implement “tax harvesting" techniques: selling assets that experience a loss and using the proceeds to buy assets with similar risk profiles in order to decrease capital gains and taxable income.

Improved investment decisions: recent academic studies highlight that robo-advising services tend to increase investors' risk-adjusted returns. This partly is a result of static changes in portfolio choices, such as improving diversification and thereby, reducing risk for a given level of expected returns. However, higher risk-adjusted returns may also occur over time, by allowing investors to rebalance their portfolios in such a way as to stay closer to their target risk-return profiles.33

Key research findings on the impact of robo-advice

- A study of a portfolio optimiser targeting Indian equities found that robo-advice was beneficial to under-diversified investors, by increasing their portfolio diversification, reducing their risk and boosting their actual mean returns.34 However, the study also claims that not all investors are winners: the use of the robo-advisor did not improve the performance of already-diversified investors.

- Another study of the impact of a large U.S. robo-advisor on a population of previously self-directed investors35 outlined a number of interesting findings. For example, robo-advice users reduced their money market investment and increased their bond holdings. Also, they decreased their idiosyncratic risk by reducing the size of individual stocks and active mutual funds, while raising exposure to low-cost indexed funds. Furthermore, their portfolios' home bias was reduced by an increase in the international equity and fixed income diversification. On a different sample of investors, another study pointed to a rise in diversification by users of a U.S. robo-advisor.36

- Amundi’s research33 focused on the influence of a large French robo-advisor on employees’ saving plans found that relative to self-management, using the robo-advice services is associated with an increase in individuals' investments and net risk-adjusted returns. Investors invest more in equities and rebalance their portfolios in a way that keeps their allocations closer to their target allocations. In fact, two thirds of their performance improvement is due to the introduction of dynamic rebalancing. Conversely, self-directed investors have a tendency to invest passively, letting their asset allocations drift following market movements.

- Increased risk taking was also highlighted by a study focused on a Chinese robo-advisor. Using unique account level data on consumption and investments (Ant Group), robo-adoption helped households move towards optimal risk-taking, and thereby reduced their consumption volatility.37

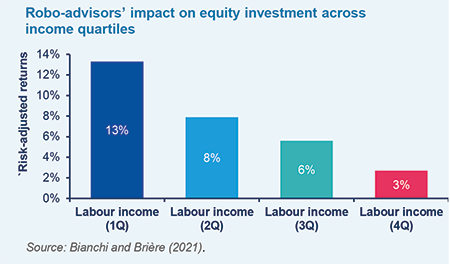

Financial inclusion: an important promise of robo-advisors is to promote financial inclusion. Offering financial services often involves substantial fixed costs, which can make it unprofitable to serve poorer consumers. New technologies offer a dramatic reduction in the cost of reaching individuals who have been traditionally under-served.38 Robo-advisors typically require a lower amount of capital to open an account and charge lesser fees than human advisors.

Academic studies on robo-advising and financial inclusion are scarce, but the initial results seem to support the above claims. A research paper focused on the effects of reducing the minimum size of a major U.S. robo-advisor’s account (from $5,000 to $500) showed that, thanks to this reduction, there was a 59% increase in the share of "middle class" participants (with wealth between $1,000 and $42,000). However, there was no increase in participation by households with wealth below $1,000.39 In addition, Amundi’s research33 showed that investors which engaged with robo-advisors increase their risk exposures and risk-adjusted returns, particularly investors with smaller portfolios (or lesser income) and lower equity exposure (see figure).

Do financial services need to adapt?

The real disruption caused by Artificial Intelligence and new technologies will be the increasing importance of successfully combining human talent and the technology evolution; this will determine the winners and losers of the future.

New technologies have made investment more attractive to retail investors. However, they have also led to new types of investment behaviours which are sometimes more risky and subject to additional investment biases. Can the financial industry offer these new investors the tools and services they need to be successful?

- Financial education: these new investors are eager to learn more about investment. A recent Schwab (2021) survey shows that more than 90% of them would like to access information and tools to do their own research, or receive educational material to improve their investment skills. Financial institutions could develop educational programs that promote financial literacy: for example, personalised coaching, reiteration of sound investment principles and information provision in times of market turbulence. Some banks have already developed new types of apps to increase investment knowledge, including virtual reality learning modules and popular video games with embedded financial concepts (e.g. Ally Bank offers services on a famous video game, Animal Crossing).

- Bespoke digital advice or hybrid advice: in a recent survey ran by the World Economic Forum and BNY Mellon (2022), 80% of retail investors say that being able to have access to financial advice is important in making investment decisions. However, less than half of them actually receive advice from a human or robo-advisor. Offering wider access to digital financial advice (for example, using improved chatbots which make use of the recent advances in large language models), and behavioural “debiasing” on all investment platforms would fill this gap as well as hybrid or human advice.

- Customised portfolios: greed and seeking novelty have led many new investors to turn to individual stocks or crypto assets, and led to a lack of diversification in their portfolios. Platform companies and digital-first players have advantages in offering attractive digital tools, but typically do not possess the financial knowledge of what should be the best products or services to offer. Giving wider access to diversified investment products customised to investors’ needs (e.g. direct indexing, investment products with personalised guarantees, or funds which are a good fit for investors’ preferences or personal risks ) would be key.

To know more:

Amundi Institute Research on retail investors' behaviour

Behavioural Biases Among Retail and Institutional...

Augmenting Investment Decisions with Robo-Advice

Robo-Advising: Less AI and More XAI?

Responsible Investing and Stock Allocation

- Brière M., Calamai T., Di Giansante F., Huynh K. and Novelli R. (2023), “Behavioral Biases among Retail and Institutional Investors”, Amundi Working Paper.

- Bonelli M. & Derrien F. (2022), "Altruism or Personal Benefits? ESG and Participation in Employee Share Plans

- Brière M., Poterba J. & Szafarz A. (2022), "Precautionary Liquidity and Retirement Saving", AEA Papers and Proceedings 2022, 112: 147-150.

- Bianchi M. & Brière M. (2022), "Augmenting Investment Decisions with Robo-Advice", SSRN Working Paper N°3751620.

- Brière M., Poterba J. & Szafarz A. (2021), "Choice Overload? Participation and Asset Allocation in French Employer-Sponsored Saving Plans", NBER Working Paper N°29601.

- Bianchi M. & Brière M. (2021), "Robo-Advising: Less AI and More XAI?", "Machine Learning and Data Science for Financial Markets: A Guide To Contemporary Practices", Ed. Capponi A. and Lehalle C.A., Cambridge University Press.

- Brière M. & Ramelli S. (2021), "Responsible Investing and Stock Allocation", SSRN Working Paper N°3853256.

References

- In particular, in the U.S., the introduction of new digital trading platforms with no minimum investment accounts, zero-commissions as well as fractional share trading have reduced barriers for retail investors.

- Charles Schwab, (2021), “The Rise of the Investor Generation”, Schwab Generation Study.

- Deloitte (2021), “The Rise of Newly Empowered Retail Investors”, Deloitte Center for Financial Services.

- Andraszewicz S., Kaszás D., Zeisberger S. & Hölscher C. (2023), “The Influence of Upward Social Comparison on Retail Trading Behaviour”, AMF (2022), Dashboard of active retail investors - N°5 – January 2022. Forbes (2022),”Empowering the Asian Retail Investor”, November 2022.

- The UK Leverage Trading Report (Investment Trends, 2021) shows that the number of people in the UK trading FX increased by 23% over the 12 months to May 2021. A survey by the trading portal, Forexsuggest.com, indicates that the average African FX brokerage saw trading volumes rise by more than 20% last year. There are approximately 1.3 million forex traders in Africa accessing forex trading via their smartphones.

- The disposition effect is an anomaly in behavioural finance, which refers to a tendency to sell assets that have increased in value, while keeping those that have declined.

- Source: https://www.independent.co.uk.

- Source: https://www.forbes.com and https://www.statista.com

- https://www.businessofapps.com

- Kalda A., Loos B., Previtero A. & Hackethal A. (2021),”Smart (Phone) Investing? A within Investor-time Analysis of New Technologies and Trading Behavior”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper.

- Lottery-type stocks refers to those that we consider inexpensive, volatile and showing a high level of skewness in their expected returns.

- The adviser managed assets of 300 billion RMB (approx. $43 billion) through 65 mutual funds ranging from equity and bond funds to hybrid and money market funds. Prior to the launch of the smartphone app, clients accessed a website with an internet browser, mostly on a PC.

- Cen X. (2019), “Going Mobile, Investor Behavior, and Financial Fragility”, SSRN Working Paper.

- Robinhood is an online investing platform designed to enable easy access to trading and investing.

- Barber B., Huang X., Odean T. & Schwarz C. (2020), “Attention Induced Trading and Returns: Evidence from Robinhood Users”, SSRN Working Paper.

- Kalda A., Loos B., Previtero A. & Hackethal A. (2021),”Smart (Phone) Investing? A within Investor-time Analysis of New Technologies and Trading Behavior”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper.

- Kahneman D. (2011), “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York.

- Cookson J.A., Engelberg J.E. & Mullins W. (2022), “Echo chambers. Review of Financial Studies”, 36(2): 450-500. Chawla N., Da Z., Xu J. & Ye M. (2021), “Information diffusion on social media: Does it affect trading, return, and liquidity?” SSRN Working Paper.

- Chen H., De P., Hu Y. & Hwang B.H. (2014),”Wisdom of crowds: The value of stock opinions transmitted through social media”, Review of Financial Studies. 27(5): 1367-403. Jame R., Johnston R., Markov S. & Wolfe M. (2016), “The value of crowdsourced earnings forecasts”, Journal of Accounting Research 54, 1077-1110. Bartov E., Faurel L. & Mohanram P. (2018), “Can Twitter help predict firm-level earnings and stock returns?” The Accounting Review 93, 25-57.

- Bartov E., Faure L. & Mohanram P. (2018), “Can Twitter help predict firm-level earnings and stock returns? The Accounting Review 93, 25-57.

- Jin X., Zhu Y. & Huang Y.S., (2019), “Losing by learning? A study of social trading platform”, Finance Research Letters. 1; 28:171-9.

- Gemayel R. (2016), “Social trading: an analysis of herding behavior, the disposition effect, and informed trading among traders under a scopic regime”, PhD thesis, School of Management & Business King’s College London, London, UK.

- Röder F. & Walter A. (2017), “What Drives Investment Flows into Social Trading Portfolios?” SSRN Working Paper. Kromidha, E. and M. C. Li (2019), “Determinants of leadership in online social trading: a signaling theory perspective”, Journal of Business Research 97, 184–197.

- Heimer R.Z. (2016), “Peer pressure: Does social interaction explain the disposition effect”, Review of Financial Studies 29(11): 3177–3209.

- Based on transactions from clients’ checking accounts (5 million) to retail crypto platforms (J PMorgan Chase clients). Wheat C. & Eckerd G. (2022), “The Dynamics and Demographics of U.S. Household Crypto-Asset Use”, JPMorgan Chase Institute.

- Among JPMorgan Chase clients, 20% of millennials use crypto assets, which is substantially more than the X Generation (11%) and baby boomers (4%). There are also large differences across races, with Asian being more likely to invest.

- Weber M., Candia B., Coibion O. & Gorodnichenko Y. (2023), “Do You Even Crypto, Bro? Cryptocurrencies in Household Finance”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper.

- Di Maggio M., Williams E. & Balyuk T. (2022), “Cryptocurrency investing: Stimulus checks and inflation expectations”, SSRN Working Paper.

- Bitcoin is the most commonly held cryptocurrency, but most crypto holders own multiple currencies (e.g. Ether and Dogecoin).

- The crypto winter refers to the crypto winter of 2022.

- Cornelli G., Doerr S., Frost J. & Gambacorta L. (202),”Crypto shocks and retail losses”, BIS Bulletin No 69.

- Lammer D.M., Hanspal T. & Hackethal A. (2019),”Who are the Bitcoin investors? Evidence from indirect cryptocurrency investments, SAFE Working Paper, No. 277.

- Bianchi M. & Brière M. (2022), "Augmenting Investment Decisions with Robo-Advice", SSRN Working Paper 3751620.

- D'Acunto F. & Rossi A.G. (2020), “Robo-advising”, SSRN Working Paper 3545554.

- Rossi A. & Utkus S. (2019), “The needs and wants in financial advice: Humans versus robo-advising”, George Washington University Working Paper.

- Reher M. & Sun C. (2019), “Automated financial management: Diversification & account size flexibility”, Journal of Investment Management 17(2), 1:13.

- Hong C.Y., Lu X. & Pan J. (2020), “Fintech adoption and household risk-taking: from digital payments to platform investments”, National Bureau of Economic esearch Working Paper 28063.

- Philippon T. (2019), “On Fintech and Financial Inclusion”, NBER Working Paper No. W26330.

- Reher M. & Sokolinski S. (2020), “Robo Advisors and Access to Wealth Management”, SSRN Working paper.

The author would like to thank Pascal Buisson, Laura Fiorot, Matteo Germano, Cécile Moreau, Chris Morgan, Paula Niall, Myriam Oucouc, Ernst Osinga and Fannie Wurtz for their valuable comments.